Anne Larsen’s post is part of our Revealing Voices blog series.

It has been stated that Anna Maria van Schurman’s defence of women’s higher education was timid and conservative because she did not oppose the sexual division of roles, unlike Marie de Gournay, her radical revisionary peer, who contended that women should take on the same public roles as men. I would argue, however, that van Schurman’s courageous and publicly delivered challenge to the educational power structures of her day was radical and far-reaching for her time.

I first came across her Latin letters and scholastic treatise on women’s higher studies in Joyce Irwin’s 1998 translation in “The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe” series. Intrigued, I then read the 1646 French adaptation of these letters by Guillaume Colletet, A Famous Question: Is it necessary, or not, that girls be learned? and the 1659 English translation by Clement Barksdale, The Learned Maid or, Whether a Maid may be a Scholar? While working on an intellectual biography of her, I discovered that she stood squarely in the late humanist tradition of innovative women polemicists such as Moderata Fonte, Lucrezia Marinella, and Marie de Gournay, and that she paved the way for later seventeenth-century female intellectuals such as Dorothy Moore, Bathsua Makin, Mary More, Gabrielle Suchon, Damaris Masham, Mary Astell, and others. In fact, she injected into the seventeenth-century debate over women’s education the notion of equality of access to education with its implicit transformative potential for women. How so?

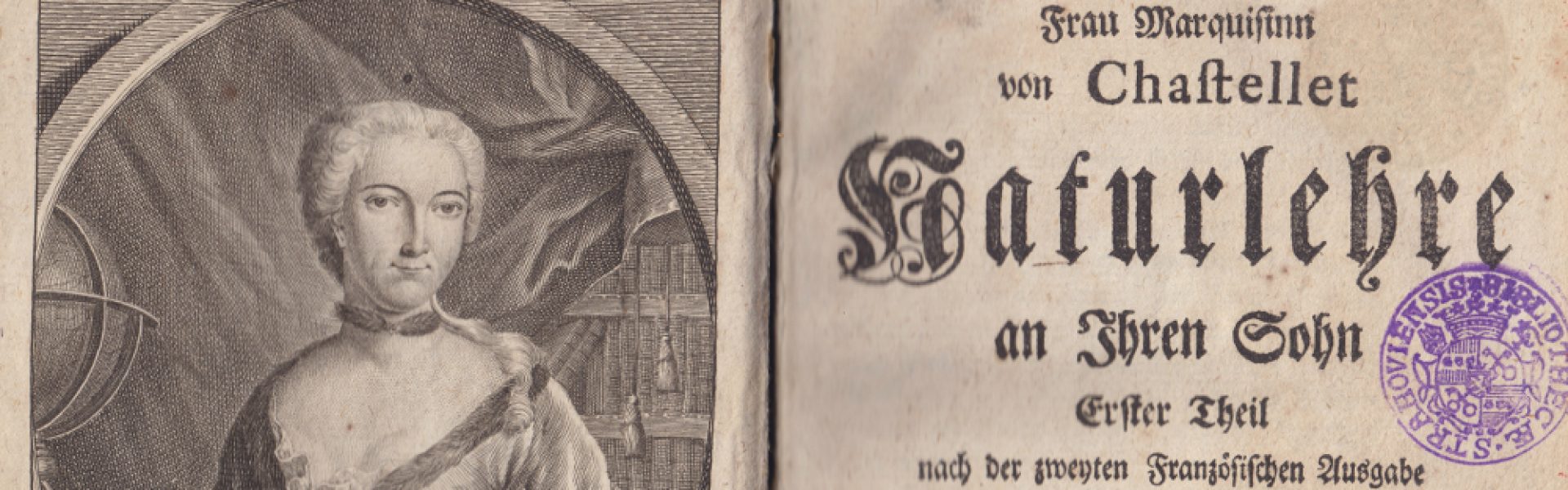

Already as a young child, van Schurman imbibed learning and excelled at it. She also stood out in the amateur arts popular among the Dutch elite such as intricate paper-cutting, wax modelling, glass and copper engraving, and miniature painting. She was one of the few women in the Dutch Republic who mastered calligraphy. Below are several self-portraits and her writing tools.[1]

In her early twenties, she met André Rivet, a French Calvinist theologian and governor of the young prince of Orange at The Hague, who became her père d’alliance (covenant father) and a regular correspondent. She informed him that she was working on a book on how women like her should make the most of their leisure.

Then, a life-changing event occurred. On the founding of the University of Utrecht in March 1636 – in the city where she lived and in the same year as the founding of Harvard – she was invited to compose the customary Latin ode, to which she added poems in Dutch and French. It’s somewhat surprising that she was offered such a public invitation, since women were barred from university study. But van Schurman was an exceptional Latinist, not merely verbally fluent but with a rare command of classical (Ciceronian) Latin which few women could display. Even more surprising is that she seized the occasion to issue an activist call for gender integration. In her ode, she boldly petitioned officials of the new university for a space not just for herself but for all women and she explained her views on the goals of education. Her Latin and Dutch poems were immediately published, making her an instant celebrity.

Soon after, the rector of the university, Gisbertus Voetius, a family friend and her neighbour, made a stunning exception for her. He invited her to attend lectures in theology and philosophy, and to study biblical and rabbinic Hebrew, as well as oriental languages (Arabic, Syriac, and Aramaic). She did so, hidden from the male students in a small closet-like space with a lattice grid. She also studied on her own Persian, Samaritan, and Ethiopian, and even compiled an unpublished Latin-Ethiopian grammar.

Van Schurman defended women’s advanced education by answering in the affirmative: “Is the study of letters fitting for a Christian woman?” Such a question would have made perfect sense at the time. Sarah Hutton explains that early modern women fought for the liberty to learn, to think, and to philosophize within the normative structures of religion, gender, class, and their own life circumstances.[2] Thus van Schurman’s defence of women’s higher education is linked to speculative learning not as an end in itself but as directly relevant to women’s duties—religious, gendered, familial, and circumstantial.

By defending equal access to a university education, she thereby critiqued unequal socio-political structures. Women with leisure time and some financial standing should not be limited, she thought, to “sewing with the needle and spinning the distaff,” then considered “an ample enough school for women”:

“By what law, I ask, have these things become our lot? Is it by divine law or human law? Never will they demonstrate that these restrictions, by which they force us into line, have been prescribed by fate or determined by God.” Van Schurman to Rivet, 6 November 1637, in Dissertatio and Opuscula

To move beyond the customary practice of female exclusion from institutions of power and learning—colleges and universities, seminaries and scientific academies—women’s ability to reason had first to be recognized. It is here that we must look to uncover the political efficacy of van Schurman’s legacy. She did not, to be sure, alter social structures and the sexual division of the sexes, a transformative change that came historically much later. But she did participate in the early development of a rights discourse by creating a precedent for women, the right to attain serious knowledge and to appropriate a rhetoric constituting a form of political influence. Timid and conservative? I think not.

[1] Image credits:

Top right: Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1633. Self portrait. Engraving. (16.6 x 15 cm) RISD Museum, Providence, RI. Link here.

Top left: Van Schurman, Anna Maria. Early 17th century. Self portrait. Print engraving on paper. (17 x 12.5 cm) Collection Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, Netherlands. Link here.

Bottom left: Postcard reprint of the writing case of Anna Maria van Schurman. Photo. Museum Martena, Franeker, The Netherlands

Bottom right: Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1640. Self portrait. Pastel on paper. (32 x 25 cm) Museum Martena, Franeker, The Netherlands. Link here.

[2] Sarah Hutton, “Liberty of Mind: Women Philosophers and the Freedom to Philosophize,” in Women and Liberty, 1600-1800: Philosophical Essays, ed. Jacqueline Broad and Karen Detlefsen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 123-35.

Anne R. Larsen is Senior Research Professor and Lavern and Betty DePree Van Kley Professor Emerita of French at Hope College (Holland, Michigan). Recent publications include Anna Maria van Schurman, “The Star of Utrecht”: The Educational Vision and Reception of a Savante (2016); Early Modern Women and Transnational Communities of Women (with Julie Campbell, 2009); Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance: Italy, France, and England (with Diana Robin and Carole Levin, 2007); and From Mother and Daughter: Poems, Dialogues, and Letters of Les Dames des Roches (2006). Her co-edited translation with Steve Maiullo of van Schurman’s Latin and French manuscript letters and poems held at The Hague’s Royal Library is forthcoming from Iter Press and “The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe” series.