Deborah Boyle’s post is part of our Revealing Voices blog series.

I first heard about Margaret Cavendish at a regional conference in 2001, and I was fascinated. I borrowed the presenter’s copy of Paper Bodies—a collection containing Blazing World, Cavendish’s autobiography, and a few of her poems—for the weekend. Looking for more Cavendish to read after that, I found Margaret Atherton’s little volume of selections from various early modern women philosophers, which included selections from Cavendish’s Philosophical Letters. As I read through Atherton’s book, I realized how little I knew about early modern women philosophers. Somehow I had majored in philosophy (at a women’s college, no less!) and completed a Ph.D. in the history of modern philosophy without knowing about any of these women except Princess Elisabeth! My curiosity about them was mingled with a good dose of embarrassment at my ignorance.

I decided that the best way to learn more about early modern women philosophers would be to teach a course on them, so that’s what I did in Fall 2002. My eleven intrepid undergraduates and I grappled with texts that were new to all of us, by Princess Elisabeth, Anne Conway, Margaret Cavendish, Mary Astell, Damaris Masham, and Catharine Trotter Cockburn.

One challenge as I was designing the course was the dearth of modern editions of texts. There was Allison Coudert and Taylor Corse’s edition of Anne Conway’s Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, which had come out in 1996. Eileen O’Neill’s edition of Cavendish’s Observations upon Experimental Philosophy had just come out the year before, in 2001. But there was as yet no good translation of Princess Elisabeth’s letters to Descartes—Lisa Shapiro’s volume was not to appear until 2007. Astell’s A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, edited by Patricia Springborg, had been published a few months before my class started, but I also wanted my students to read parts of Astell’s Christian Religion, and there was no modern edition of that; Jacqueline Broad’s edition was eleven years in the future. And when it came to Masham and Cockburn, there was nothing but the selections in Atherton’s book. I wanted to pair Masham’s discussion of educating women in Occasional Thoughts with Astell’s Serious Proposal, but without a modern edition of Masham’s book, students would have to deal with scans of the original, complete with antiquated spelling, capitalization, and punctuation, not to mention the archaic font and long S.

And when I started writing a paper on feminist interpretations of Cavendish’s natural philosophy, I found I too would have to deal with archaic fonts and the long S, because the texts I was interested in were simply not available in modern editions. The college where I teach did not yet have a subscription to Early English Books Online (EEBO), so my only choice was to order the texts on microfilm and print them out, page by page.

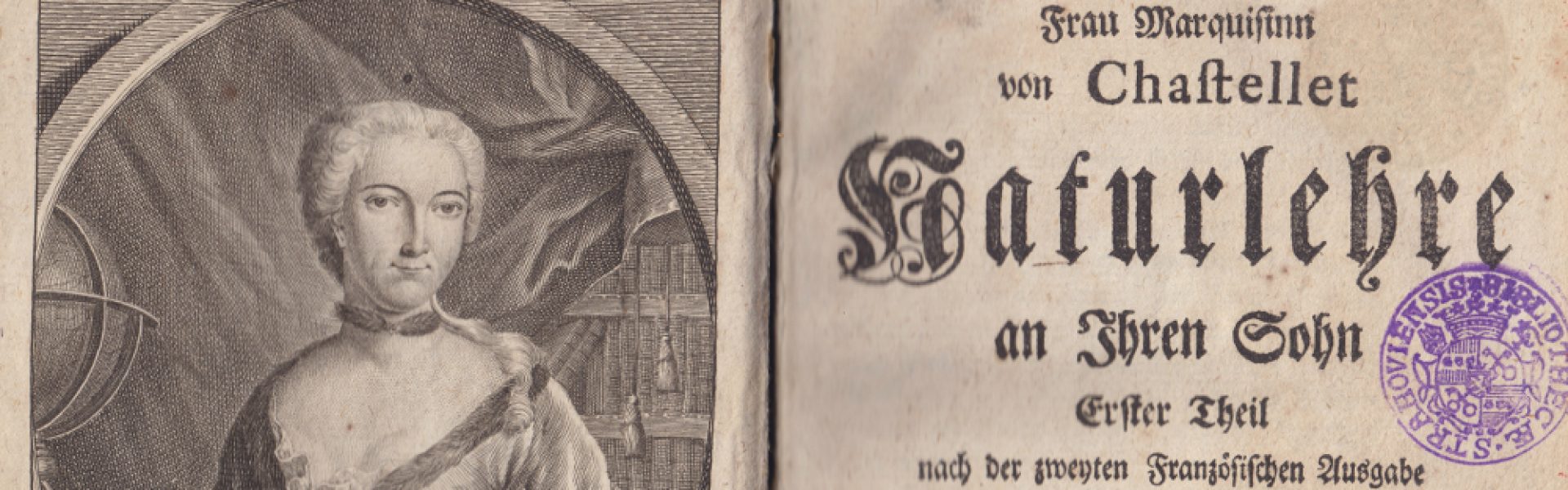

The situation has undoubtedly improved since then. Lisa Shapiro (Simon Fraser University) and Marcy Lascano (University of Kansas) have a new textbook under contract with Broadview Press, Early Modern Philosophy: An Anthology of Primary Sources, which will include works by about a dozen women philosophers, as well as male philosophers (both the usual cast and some who are less often included in textbooks, the so-called “minor” figures). When this is published, it should go a long way toward introducing the next generation of historians of philosophy, at a much earlier stage of their education, to texts by early modern women philosophers. And in addition to the modern editions I mentioned already, more are in the works; Broadview Press will soon be publishing an edition of Cavendish’s Grounds of Natural Philosophy, and Oxford University Press has begun a “New Histories of Philosophy” series, with editions forthcoming of works by Cavendish, Émilie Du Châtelet, Sophie de Grouchy, Mary Shepherd, and others. I myself have prepared an edition of selections from Mary Shepherd’s works for the Library of Scottish Philosophy, which has just been published by Imprint Academic.

It is also now relatively easy for intrepid scholars to find works by early modern women philosophers even when there are no modern editions. Many texts are now available online, either through subscription databases like EEBO (to which my library now subscribes, thank goodness) or through free sites like Google Books, Project Gutenberg, or The Internet Archive. And Project Vox provides an invaluable service in cataloguing primary sources, including links to digitized versions where those exist.

Still, this situation is less than ideal. People without a university affiliation, or at institutions that don’t have the resources to subscribe to EEBO, will find it very difficult to track down texts like Cavendish’s Grounds of Natural Philosophy or Worlds Olio, which are not available online. Digitized texts are not always fully readable; when I started researching Lady Mary Shepherd, I found that the Google Books scan of her 1827 Essays on the Perception of an External Universe contained pages out of order, half blank, or so blurry as to be illegible. There were even pages obscured by images of the hand of the person who did the scan.

More importantly, texts by early modern women philosophers need to be available to more than just intrepid scholars. Without affordable, accessible modern editions of these texts, they will remain the purview only of specialists who go to the trouble of tracking them down. Newcomers interested in early modern women philosophers need readable, modernized editions, with information by reliable editors about the historical and philosophical context. Instructors need affordable editions they can assign in classes to get the word out about these fascinating works by early modern women philosophers. With many more texts waiting to be revealed to broader audiences, it is my hope that more historians of modern philosophy will take up these projects.

Deborah Boyle is Professor of Philosophy at the College of Charleston, where she has taught for 19 years. She has published on Mary Astell, Margaret Cavendish, Anne Conway, and Mary Shepherd, as well as on Descartes and Hume. Her book about Cavendish’s philosophical views, The Well-Ordered Universe, was published by Oxford University Press in 2018, and her edited volume Lady Mary Shepherd: Selected Writings is being published in December 2018 by Imprint Academic.