Jacqueline Broad and Catherine Sutherland’s post is part of our Revealing Voices blog series.

In his biographical sketch of Mary Astell in 1752, George Ballard records Astell as ‘intimately acquainted with many classic authors. Those she admired most were Zenophon, Plato, Hierocles, Tully, Seneca, Epictetus, and M. Antoninus.’[1] In Ruth Perry’s landmark biography of Mary Astell published in 1986, Perry notes that in Astell’s correspondence, she refers to Homer, Virgil, Hippocrates and Sallust.[2] Reading classical texts would certainly go some way to account for Astell’s use of the name ‘Phylia’ which, we can reveal, she inscribed in books she owned – books now residing in the Northamptonshire Record Office (NRO) and the Old Library of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In total, these libraries contain approximately 50 books that once belonged to Astell and that bear the marks of her ownership. At least eight items are inscribed with the name ‘Phylia’ or ‘Phyliæ’.

The fact that Astell used this pseudonym in her books will be of interest to scholars looking to find further volumes from her library and further writings from her hand.

The ‘Phylia’ inscription appears in two titles at Magdalene: Fiennes’ Treason’s master-piece, and an anonymous parliamentarian work Unparalleld monarch. Additionally, ‘Phylia’ can also be made out from underneath deleted inscriptions in a further four titles: Gilbert Burnet’s Vindication of the authority, constitution, and laws of the church and state of Scotland, Simon Patrick’s Mensa mystica and Acqua genitalis, and Nicolas Malebranche’s De la recherche de la verité. (For further details on the Magdalene collection of Astell’s books, see here).

An inscription by Mary Astell in the book The Unparalleld monarch: Or, The portraiture of a matchless prince (London, 1656) in the Old Library of Magdalene College Cambridge.

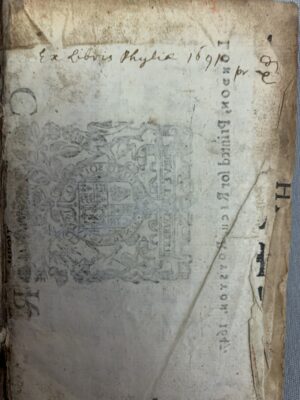

In the NRO collection, Astell’s copy of William Cave’s Primitive Christianity has ‘E Libris Phyliæ A.D. 1679’ marked in ink on the title page, with the word ‘Phyliæ’ crossed out in pencil, while the name ‘Mary Astell’ appears on the frontispiece. Astell’s copy of Richard Allestree’s The Ladies Calling also bears the words ‘Phylia’ in pencil (at the top of the title page) and ‘Ex Libris Phyliæ’ in ink (at the bottom), with the inscription ‘Mariæ Astell Ex Dono Radulphi Astell’ on another blank page.

These titles display a wide range of subject matter but there does seem to be a loose trend regarding the time period in which the name was used: the latest date at which Astell uses the ‘Phylia’ pseudonym is 1697, at the beginning of her writing career. Astell may have reserved this name for books from her youth—and for her youthful poetry. In the seventeenth century, it was a popular convention for female poets to take pen names from pastoral romances or classical sources. Astell’s contemporary Mary Chudleigh was ‘Marissa’, Elizabeth Thomas was ‘Corinna’, and, of course, Astell’s favourite poet Katherine Philips was ‘Orinda’; among Philips’ society of friends, there was also ‘Rosania’ (Mary Aubrey), ‘Lucasia’ (Anne Owen), and ‘Ardelia’ (Mary Harvey). On the opening flyleaf of the NRO volume of the Ladies Calling, bound together with a note ‘Mary Astell her Book given her’, there is a poem in Astell’s hand-writing signed by ‘Phylia’. It reads (in part):

Let modish Ladies in their dress excell,

Prove Criticks in the art of speaking well;

For Beauty and for Wit the Palm obtain,

At something beyond these my Soul shall aim.

I’le in this glass reform my dress and [Face?]

Not by the Rules of Fashion but of [Grace?]

With outward Ornaments I would not [shine?]

May I but be within bright and div[ine?]

And study to attract a Lover then

Fairer than all the fairest Sons of Men.

And ne’re take up with sublunary things,

But scorn all Loves beneath the King of Kings.

Decking my Virgin Soul for his embrace

Who more regards the heart than dress or Face,

My amorous thoughts I’le on his Beauty place,

Till those espousals which we here contract,

From vows and wishes, be reduc’d to act

And ravishing fruition in his arms,

Who is the scourse of bliss, and purest Charms;

Then I a Virgin and a Bride shall be,

Without the fears of Widdowhood, to all Eternity.

sic resolvat Phylia

Mar. 31.

1697

With its focus on inward virtue and divine love, the poem is typical of Astell, who wrote a manuscript book of poetry in her early twenties exploring similar themes.[3] The Latin phrase ‘sic resolvat Phylia’ loosely translates as ‘it resolves’ or ‘so resolves Phylia’.

It is possible that Astell found the name ‘Phylia’ in Hobbes’ 1679 translation of Homer’s Odyssey, where Hobbes transliterates the term from the Greek as ‘Phylia’ but does not attempt to translate it.[4] In the Oxford Greek-English Lexicon, the term is translated as ‘wild olive’ and appears in a very small grouping of classical Greek literature.[5] Most notably, it appears in epic poetry: in addition to the Odyssey it appears here in Nonnos’ Dionysiaca:

But I will tell you my fate, father, in due order. There was a

longleafy thicket, part of wild-olive, part of orchard olive. Like a

fool I left Phylia’s namesfellow groth and scrambled up a handy

branch of the pure olive, to spy out the naked skin of Artemis.[6]

‘Phylia’ also appears in other Greek literature such as Pausanias’ description of Greece, 2.32.10, also in the context of being some kind of wild olive plant, and Philostratus of Athens’ Gymnasticus 43. An alternative translation of ‘Phylia’ is ‘thorn’, which may point to Astell’s famously prickly character.

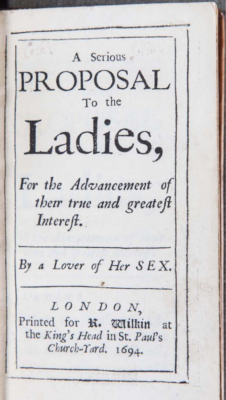

One final suggestion is that, with this pseudonym, Astell alludes to philia, the ancient Greek concept of friendship or friendly feeling, often contrasted with eros or sexual desire, and agape or brotherly love.[7] Philia is characterised by alove for the virtuous qualities of one’s friend rather than love of a carnal nature. Astell’s Letters Concerning the Love of God, her correspondence with John Norris, explores in some detail the ideas of platonic love, benevolence, and desire. Her most famous work, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, also extols the benefits of a noble friendship: not a fraternal philia between soldiers on the battlefield (the common Greek notion), but rather a virtuous love among like-minded women in a learned academy.

Further discussion of Astell’s newly rediscovered library at Magdalene and her use of the name ‘Phylia’ will appear in forthcoming publications by Catherine Sutherland and Jacqueline Broad.

[1] George Ballard, Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain (Oxford: W. Jackson, 1752), p. 449.

[2] Ruth Perry, The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. (Chicago and London: University of Chicago, 1986), p. 303.

[3] See Perry, Celebrated Mary Astell, pp. 400-54.

[4] Thomas Hobbes (trans.), Homer’s Odysses (London: J[ames] C[ottrell] for W. Crook, 1675), p. 67.

[5] Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, and Henry Stuart Jones, A Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996).

[6] William Rouse (trans.), Dionysiaca (London: Heinemann, 1962), p. 200.

[7] Bennett Helm, ‘Love’, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward Zalta (2017), <https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/love/>.

Jacqueline Broad is an Associate Professor of Philosophy in the School of Philosophical, Historical, and International Studies at Monash University, Australia. She is the author of The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue (OUP, 2015) and the Series Editor of Cambridge University Press’s new Elements series on Women in the History of Philosophy.

Personal website: http://jacquelinebroad.com/

Monash website: https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/jacqueline-broad

Catherine Sutherland is the Deputy Librarian of the Pepys Library and Special Collections at Magdalene College, Cambridge. She has previously published on the ‘collecting friendship’ between Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn and regularly blogs about book history and provenance on the Magdalene Libraries’ blog.

Website: https://www.magd.cam.ac.uk/pepys

Blog: www.magdlibs.com