Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, Countess Palatine, Abbess of Herford

“I have so far found that only you understand perfectly all the treatises which I have published up to this time… I know of no mind but yours to which all things are equally evident, and which I therefore deservedly term incomparable.”

—René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy (1644), dedication to Princess Elisabeth.

Elisabeth, Princess Palatine of Bohemia, was a remarkable woman living during remarkable times. She experienced a devastating and protracted war, years of exile, political strife, executions of family members, and a final period as a political authority and protector of religious refugees. She was known alternately as a great intellectual, a philosopher, a “Cartesian Princess,” and a political figure. With familial connection to Prussia and England, her family placed her at the very center of European political life in the 17th century. But Elisabeth was not content merely to play the role of a member of a royal household. From an early age, she took various measures to ensure that she would sit at the nexus of European intellectual life as well. As the head of Herford Abbey, she courageously used her personal influence to provide refuge for persecuted religious groups—such as the Labadists and the Quakers—who were considered too radical by many religious and political institutions in the late 17th century. She spent years building an immense intellectual network through her personal connections, her correspondence, and her own actions as the leader of the Abbey. She personally met with, corresponded with, or was known to, the following major figures from the 17th century: Descartes, Leibniz, Malebranche, Henry More, Anne Conway, Francis Mercury van Helmont, William Penn, Constantjn Huygens, and Anna Maria van Schurman. In many ways, then, to study Elisabeth’s life is to study European intellectual life in the 17th century.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Born in Heidelberg just after Christmas Day in 1618, Elisabeth was the oldest daughter of a family that blended Bohemian and English royalty. Her father was Frederick V, Prince of Bohemia, and her mother, Elisabeth Stuart, was the daughter of James I of England. Through her parents, she was connected to several of the most important events of the century. Most prominently, her family’s fortunes were intertwined with the Thirty Years War, one of the most tumultuous events in Europe during the 17th century. In his famous History of England, David Hume called that war “the most destructive in modern annals” (Hume 1850, V: chapter 61, page 454). The War upended her family’s life, sending them away from Prussia into exile in Holland, where they would remain for years. Her family also gave her intriguing connections to many key early modern figures. For instance, her father fought for King Gustav of Sweden, who was the father of Queen Christina, the patron of Descartes near the end of his life and a great inspiration to women intellectuals throughout the early modern period. Elisabeth’s maternal uncle was King Charles I of England, who was beheaded in 1649 during the Civil War and his struggles with Parliament. Elisabeth’s cousin was crowned King Charles II of England in 1660 after the Civil War had ended and the monarchy was restored. Indeed, in 1649 alone, Elisabeth and her family were involved in two of the most momentous events in the whole century: through her brother, she was connected to the eventual development of the peace treaty of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years War; and through her mother, to the execution of Charles I that same year (in February). Suffice it to say that Elisabeth lived during chaotic and difficult times.

During her early years, Elisabeth had a broad education through tutors and her family connections. For instance, she learned mathematics from Jan Stampioen, who also tutored Constantijn Huygens, an important Dutch figure and the father of the great mathematician and philosopher Christiaan. Before long, Elisabeth became known as “La Grecque” for her love of philosophy and knowledge of Greek. After a childhood in Germany, largely in Heidelberg and Berlin, her family went into exile in Holland, living in The Hague in the 1630s. During this time period, she was mentored by the great philosopher, linguist, and polymath Anna Maria van Schurman (the first woman to attend university in Europe), who advised Elisabeth on a range of subjects and suggested numerous readings for her to consider. Years later, Elisabeth returned this generosity by providing van Schurman and some of her colleagues with safe haven in the face of potential religious persecution. Elisabeth demonstrated a keen interest in philosophical and intellectual controversy and discussion. Life in The Hague turned out to be the first crucial stage of Elisabeth’s intellectual development, for she used this opportunity to shape a major intellectual community of exiles in The Hague. For instance, in 1634, at the age of only sixteen, she arranged a debate between Descartes and a Protestant Scottish minister named John Dury. Over the course of the next few years, she forged personal and intellectual connections with a wide variety of figures, including Descartes, Leibniz, Constantijn Huygens, and many others.

Binnenhof, The Hague

Elisabeth’s intense intellectual life at The Hague ended in 1646, when she left the court and resettled in Berlin for a short time, before returning to her birthplace in Heidelberg. It was her last move to Herford that enabled her once again to create a rich and thriving community of intellectual and religious exiles. Henry More became aware of Elisabeth’s philosophical talents, and there is evidence that More hoped she would accompany her mother, Queen of Bohemia, on her trip to England so that they could speak in person. These details are found in a letter that John Worthington sent to Samuel Hartlib in May of 1661 (Worthington 1847—, I: 311), which means that More’s anticipation of her visit was public knowledge to some extent. Instead of moving with her mother to England in 1661, however, Elisabeth chose instead to move to Herford in Germany. This was a fateful decision, as she became the Abbess of the convent there in 1667. This meant, as Carol Pal remarks in her Republic of Women, that Elisabeth would become the Calvinist leader of an abbey in Lutheran Germany harboring religious exiles such as Quakers and Labadists. In an age of religious wars that led to massive migration of refugees in Europe and the Americas, Elisabeth used her influence to protect those who were labeled as heretics. How Elisabeth understood religion and theology, and connected them with both politics and philosophy, is a pressing question that has yet to be fully answered.

Herford Abbey

In philosophical circles, Elisabeth is best known for her correspondence with Descartes (see section 5.1). Indeed, to scholars in the 18th century, she was known as “the leader of the cartésiennes,” the women who were counted as followers of Descartes (Harth 1992, 67). But she also forged connections, both personal and intellectual, with a remarkable range of other figures, both canonical (eventually) and otherwise. For instance, Elisabeth met Leibniz in person during her visit to Hanover in the winter of 1678 (Aiton 1985, 90-1), at which point she introduced him to Malebranche’s Conversations Chrestiennes. Leibniz later wrote Elisabeth a long letter that same year expressing his reactions to Malebranche’s ideas (Leibniz 1926, 433-38). As one would expect, because Leibniz was already developing a critical attitude toward Cartesian ideas in philosophy, he did not see eye-to-eye with Malebranche on a number of issues. This event then led to an exchange of letters between Malebranche and Leibniz in 1679 (Leibniz 1926, 2-1: 472-480). Elisabeth’s connections to figures like Descartes, Leibniz, and Penn are very well known, having been covered in depth in both history of philosophy scholarship (the former) and the history of Quakerism (the latter).

Elisabeth’s connections with women intellectuals during her era are equally impressive and significant, but perhaps less well known. For instance, she became acquainted with Henry More, the theologian and philosopher in Cambridge, who then introduced her to other influential figures, including the Viscountess Anne Conway. Having introduced van Helmont to Henry More in 1670, it seems that Conway may have sent Elisabeth some of More’s recent work the following year (Hutton & Nicholson 1992, 340). More and Conway corresponded extensively, and they mention Elisabeth on occasion (Hutton & Nicholson 1992, 498,). Elisabeth’s familial and intellectual networks intersected in this case: Elisabeth’s mother, Elizabeth Stuart, had been a friend of the first Viscount Conway (Hutton 2004, 154). In tandem, the Quaker leader Robert Barclay mentions Conway in some of his letters to Elisabeth (Hutton & Nicholson 1992, 435-36). As part of Barclay’s effort to convince Elisabeth to join the Quaker movement, he tells her of the conversion of Conway. Elisabeth apparently never met or corresponded with Anne Conway directly, but it is certainly significant that they knew of one another. Conway’s close friend Francis Mercury van Helmont, who was introduced to the Quaker movement during a visit to Elisabeth’s family’s court in Heidelberg in 1659 (Hutton 2004, 178-79), and who converted to Quakerism with Conway, also become close with Elisabeth, attending her at her deathbed (with Leibniz) in 1680. Indeed, van Helmont visited Elisabeth shortly after Conway’s death (Hutton 2004, 154).

Elisabeth’s connection to Anna Maria van Schurman, who was the first woman to attend university in the Netherlands, and who was known as “the light of Utrecht,” lasted her whole life (see especially Pal 2012). We know, at least partly through correspondence, that the young Elisabeth sought van Schurman’s advice about what to study, which classical authors to read, and in general how to fashion her own education (Pal 2012, 72-74). That fact alone, of course, is worthy of note, since it shows that Elisabeth’s inability to obtain an education through an institution of learning in some formal way was no obstacle to her obtaining a serious education – involving history, literature, philosophy, etc. – through her own means.

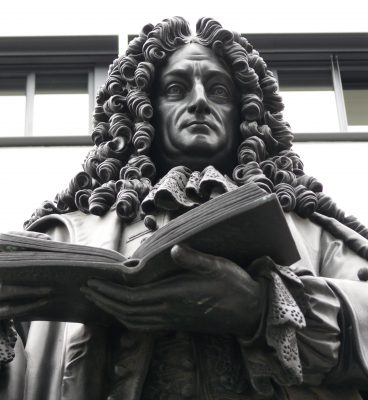

Through her family, Elisabeth’s connections to a remarkable group of intellectuals extended even into the 18th century in certain respects, after her death. For instance, in addition to her personal connection with Leibniz, and their correspondence, Elisabeth’s sister Sophie was tutored by Leibniz. Indeed, during the Hanoverian Succession, which involved the arrival of Sophie’s son George I in England in 1714 (Brown 2004, 263-65), there was considerable discussion in London at that time of whether Leibniz would accompany George’s move to England. Those in Isaac Newton’s famous circle in London were especially concerned that Leibniz’s connections with Sophie and her family might mean that he would not only move to England, but also wield considerable influence under the new regime. In the end, Leibniz did not move to England, but he would make an important decision that deepened his connections with Elisabeth’s extended familial world. Because Sophie’s son, George I, ended up in England alone – George’s wife Sophie-Dorothea remained in Germany at the Castle of Ahlden when he moved to England to take the throne – it turned out that Princess Caroline of Wales was the highest ranking female royal in England at the time. So in 1715, instead of trying to influence events in England directly, Leibniz wrote Princess Caroline a famous letter bemoaning the decay of religion and the emergence of dangerous philosophical ideas in England at that time. Leibniz mentioned especially the ideas of John Locke and Isaac Newton, who at that time was “Sir Isaac” and the President of the Royal Society in London. Caroline’s previous intellectual connection with Leibniz, including her admiration for his Theodicy, made her the perfect choice for his epistolary foray into combatting Newtonian philosophy. Indeed, Princess Caroline met Leibniz in Berlin in the late 17thcentury, where she was living under the protection and care of Sophie-Charlotte, Elisabeth’s niece. And when Sophie-Charlotte died in 1705, leaving Leibniz bereft after a long friendship, Caroline became perhaps his closest female interlocutor. As Leibniz expected, his letter to Princess Caroline was shared with Newton and his circle in London. In this way, the famous the Leibniz-Clarke correspondence was born. There is strong evidence that various editions of the Leibniz-Clarke correspondence, of which there are many, exclude Princess Caroline from the history in which she participated, even to the point of failing to note for readers that Leibniz’ “first letter” to Clarke was in fact written to Princess Caroline and not to Clarke at all (Bertoloni Meli 1999, 470)! Recent scholarship has begun to rectify such errors, noting the importance of Leibniz’s relation to, and discussions with, Princess Caroline (Brown 2004). In the end, Leibniz sent four more letters to Princess Caroline, who shared them with Newton’s circle, and Clarke sent replies to each of them. So, Caroline served as the intermediary for the most famous philosophical correspondence of the 18th century. Intriguingly, Sophie herself had served as the intermediary for a correspondence between Leibniz and Paul Pellisson, an assistant to Louis XIV (Bertoloni Meli 2002, 456-59).

Elisabeth’s Family, 1620

The two Princesses, Elisabeth and Caroline, have another important feature in common. Like Elisabeth before her, Princess Caroline was under considerable pressure to convert to Catholicism in order to make a marriage into an important political and royal family possible, but she ultimately refused and the marriage was called off. Notably, both Elisabeth and Princess Caroline made famous pronouncements later in life about their commitment to their religion. When pressed on the point about her conversion later in life, Elisabeth famously noted that she wouldn’t convert when she stood to gain a kingdom, so she would obviously not do so later in life when she stood to gain nothing. In an equally witty remark, Princess Caroline took offense at a comment by the Bishop of London after she arrived in England, noting: “He is very impertinent to suppose that I, who refused to be Empress for the sake of the Protestant Religion, don’t understand it fully” (cited in Bertoloni Meli 1999, 473). Both Elisabeth and Caroline made it clear that they would not tolerate anyone who underestimated their commitment and understanding of Protestantism.

Like nearly all women in early modern Europe—Anna Maria van Schurman in Utrecht and Laura Bassi in Bologna are important exceptions—Elisabeth was prevented from joining the intellectual communities of universities and scientific academies in her day. Even her immense influence as a member of a family that sat at the intersection of two major royal households did not allow her to break through those strictures. What is remarkable, then, is Elisabeth’s successful efforts at forming intellectual communities of her own, first at the exiled court at The Hague in her youth, and many years later during her time in Herford. The story of women participating in, and even shaping, political, intellectual and religious life through the famous salons of Europe is well known. But Elisabeth was much more than a salonière: she managed to create, not once but twice, a flourishing community of intellectual leaders and religious exiles through her powerful personality and influence. This meant that her exclusion from the institutions of European intellectual life was dramatically minimized: she simply created a robust intellectual life around herself. But there is one important consequence of the fact that so much of Elisabeth’s intellectual life was conducted through events in person: we often have very little trace of her many discussions in the historical record. We know that she had numerous meetings with a myriad of intriguing figures, including Descartes, Leibniz, William Penn, van Schurman, and many others. Yet we know very little about the questions that she asked, the arguments that she made, the positions that she explored, and so on. Through the documents, correspondences, manuscripts and publications that have survived and that are currently known, Elisabeth has become a great philosophical heroine to many scholars and students. Indeed, she was famous in her own lifetime for her philosophical abilities and for her protection of religious exiles. She even became an inspiration to figures in the 18th century, such as Émilie Du Châtelet. Nonetheless, for all that influence and fame, one thing seems painfully clear: her full story has yet to be written.

Bust of Elisabeth in front of Herford Abbey

References

- Hayes, Julie C. 1999. Reading the French Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutton, Sarah. 2004. Anne Conway: a woman philosopher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hume, David. 1850. History of England. Six volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Pal, Carol. 2012. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shapiro, Lisa. 2013. “Elisabeth, Princess of Bohemia”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), edited by Edward Zalta. Web. Accessed July 1, 2017. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/elisabeth-bohemia/

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

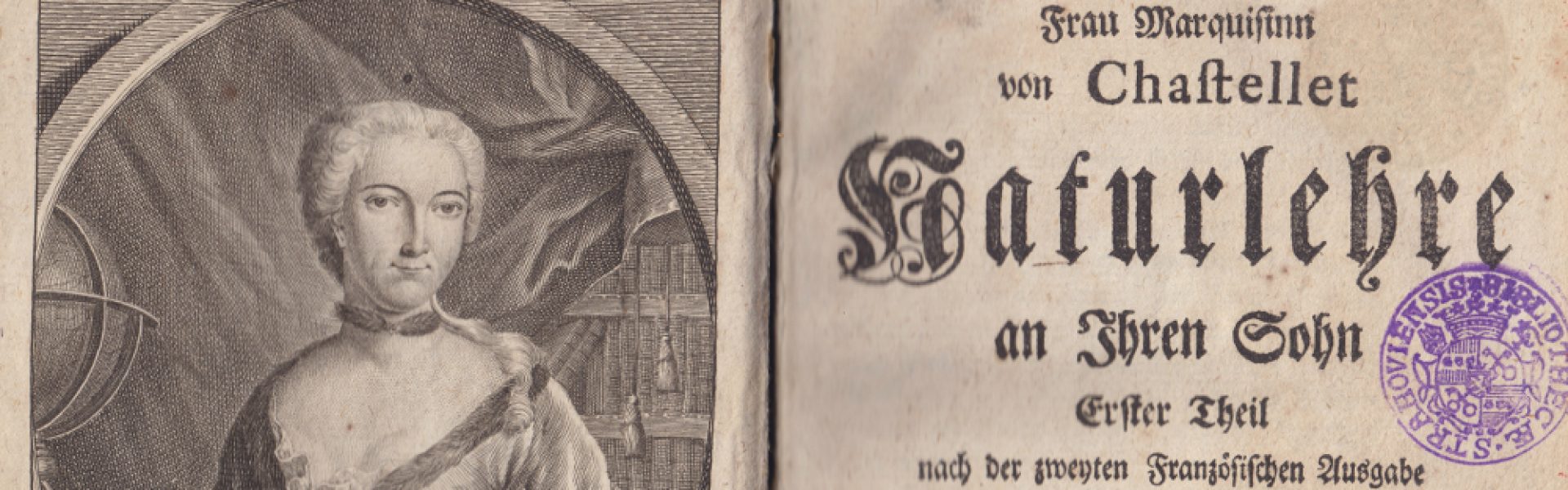

1.2 Portraits

Given Princess Elisabeth’s royal status, it is not surprising that several portraits of her exist. Some of these have been lost, but we are fortunate that most are extant today. We include two here that have been made available for use on the Project Vox website. See the References below for other sources of Elisabeth portraiture.

Portrait of Princess Elisabeth as Diana

This portrait is dated in 1642, “shortly after the 1631 group portrait of the four children of the ‘Winter King’” (Judson and Ekkart 1999, 269-70). As indicated by its title, the painting depicts Princess Elisabeth as Diana, the Roman goddess of hunting. Typically portrayed as a young woman with a bow and arrow, Diana was known for, as a virgin and an unmarried goddess, chastity and purity.

This portrait is attributed to the artist Gerard van Honthorst, a Dutch painter at the Hague. He produced many royal portraits of her family: in addition to painting Princess Elisabeth, Honthorst also painted King Charles I (Elisabeth’s uncle), Frederick V (Elisabeth’s father), Prince Rupert (Elisabeth’s brother), Queen Elizabeth (Elisabeth’s mother), and Louise Hollandine (Elisabeth’s sister). This was possible as Honthorst was recorded to be “at the court of the exiled King and Queen of Bohemia, painting portraits of the family and teaching drawing to their children” (Pal 2012, 71).

Princess Elisabeth as Diana

Elizabeth, Princess of the Palatinate

This undated portrait, currently housed at the National Portrait Gallery in the United Kingdom, was painted sometime in the mid-seventeenth century. This painting is attributed to the studio of Gerard van Honthorst, while it has an engraving in the frame by painter and engraver Crispiaen Queboren, who was active in Utrecht, dating to the same time period.

The Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery bought this work in February 1872 first under the title of “Sophia, Electress of Hanover” (Elisabeth’s sister, tutored by Leibniz). It was only in 1914 that the portrait was correctly identified as Elisabeth when its similarities to another portrait of the princess were noticed (Piper 1963, 119).

Elisabeth, Princess of the Palatinate

References

- Judson, Jay Richard, and Rudolf E. O. Ekkart. 1999. Gerrit van Honthorst (1592-1656). Doornspijk: Davaco.

- Pal, Carol. 2012. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Piper, David. 1963. Catalogue of seventeenth-century portraits in the National Portrait Gallery, 1625-1714. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- The British Museum. n.d. “Crispijn van Queborn (Biographical details).” Accessed October 23, 2018. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=110646.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.3 Chronology

| DATE | EVENT |

| 26 December 1618 | Princess Elisabeth is born in Heidelberg Castle as the oldest daughter to Frederick V, the Elector of the Palatinate, and Elizabeth Stuart, the daughter of James I of England. |

| 8 November 1620 | The weakly defended Bohemia is taken by the Spanish Ambrogio Spinola as part of the Thirty Years’ War. To escape the invaders, Elisabeth flees with her family to Brandenburg, then her grandmother’s charge in Krossen. |

| 1621-1622 | Elisabeth’s uncle Prince Maurice, Stadthalter of the Dutch Republic, offers the royal family refuge at the Hague. Most of Elisabeth’s family move there, but Elisabeth stays in Krossen, the residence of her cousin Princess Hedvig Sophia Augusta of Sweden. Elisabeth’s “natural gravity and dignity” is said to have been disciplined at Krossen. |

| 1627 | Elisabeth and her brother Charles Louis leave Krossen and join their siblings at The Hague. |

| 1627-1635 | Elisabeth’s education at The Hague consists of learning Latin, Greek, French, English, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, and German; being trained in logic and natural science; and being versed in the principles of Heidelberg Catechism, the latter of which formed her Protestant religious outlook for the rest of her life. Even at an early age, Elisabeth impresses everyone with her love of Greek and philosophy, earning her the nickname “la Greque.” |

| 1633-1634 | Elisabeth befriends Anna Maria van Schurman, probably when the latter visited Leiden to give a lecture or to hold a dispute in the great hall of the University. |

| 1637 | Descartes publishes his Discourse on the Method. |

| 1639 | Princess Elisabeth and Anna Maria van Schurman commence correspondence. |

| 1640 | Elisabeth and Descartes meet for the first time, when the latter visits The Hague. Elisabeth was already interested in his earlier philosophical writings. |

| 1641 | Descartes publishes Meditations on first philosophy. |

| 1643 | Correspondence between Elisabeth and Descartes begins with Elisabeth querying Descartes about the coherence of his account of the human being presented in the Sixth Meditation. |

| 1644 | Descartes’s Principles of Philosophy, dedicated to Elisabeth, is published. |

| 1 July 1646 | Leibniz is born in Leipzig. |

| 7-17 September 1646 | Princess Elisabeth moves to Berlin, Brandenburg. Elisabeth introduces Cartesianism to Berlin, then far behind in culture, thus strengthening the intellectual community there. |

| 1649 | Descartes’s The Passions of the Soul, prompted by and refined through discussions with Elisabeth, is published. |

| 1649 | Elisabeth’s uncle Charles I is executed in England, following Oliver Cromwell’s victory over Imperial troops. Hearing the news, Elisabeth falls into serious illness. |

| 11 February 1650 | Descartes passes away at the court of Queen Christina of Sweden, the daughter of King Gustav, for whom Elisabeth’s father fought earlier in the century. |

| 1650 or 1652 | Elisabeth returns to Heidelberg by invitation of her sister Sophie. At the University of Heidelberg, which her brother Charles Louise reconstructed from the ruins of the Thirty Years War, she engages with teachers and actively disseminates Cartesianism to students. |

| 1657 or 1658 | Louise Hollande converts to Catholicism and disappears from her mother at The Hague. Both the Queen and Elisabeth are greatly distressed, though Elisabeth did not bear any grudges later. Because of her departure, Elisabeth is now considered for candidacy to the Abbess of Herford Abbey. |

| 1661 | Elisabeth is appointed successor to her cousin, Elizabeth Louise, to the position of Abbess of Herford. |

| 1667 | Elisabeth is formally named Abbess of the Abbey at Herford after Elizabeth Louise’s death. |

| 1670 | Elisabeth provides Anna Maria van Schurman and her Labadists asylum at the Abbey; this is to the dismay of her family, who are not sympathetic towards “mystical doctrine.” |

| 1676 | Elisabeth provides asylum to the Quakers at the Abbey. |

| 4 May 1676 | Anna Maria van Schurman dies in Friesland. |

| 1677 | William Penn visits Elisabeth at Herford Abbey. |

| Winter 1678 | Elisabeth meets Leibniz. |

| 1680 | Leibniz visits Elisabeth at Herford. |

| 8 February 1680 | Elisabeth dies at age 62. Her sister Sophie announces Elisabeth’s death (on February 12). Francis Mercury van Helmont, a close friend of Anne Conway’s, and Leibniz attend to Elisabeth at her deathbed. |

| 1714 | Sophie’s son, Elisabeth’s nephew, becomes George I of England as part of the famous Hanoverian Succession. |

| 14 November 1716 | Leibniz dies in Hanover. |

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2. Primary Sources Guide

Although Elisabeth was a prolific correspondent—she wrote to everyone from philosophers like Descartes and Leibniz to Quaker leaders like William Penn to various members of her extended, royal family—she never published a work of her own. In addition, scholars have not found any manuscripts of hers, so her unpublished extant writings consist entirely of correspondence and various personal items. As for her correspondence, many of her letters have gone missing or were destroyed during the course of the Thirty Years War and her family’s long exile in Holland. Enough of her correspondence with various figures did survive for Madame Blaze de Bury to compose Memoirs of Princess Palatine (1853), the first biography of Elisabeth. Then, by sheer chance in the late 1800s, an antique bookseller was rummaging through the archives of Rosendael castle near Arnheim, in the Netherlands, and found a bundle of papers. The French philosopher Alexandre Foucher de Careil recognized these papers as her responses to Descartes. Foucher de Careil’s book, Descartes, la princesse Élisabeth et la reine Christine d’après des lettres inédites (1879), thus became the first publication dedicated to their complete exchange. The most important modern edition of the Elisabeth-Descartes correspondence was published in 2007 by Professor Lisa Shapiro.

References

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2002. Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pal, Carol. 2012. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shapiro, Lisa, ed. 2007. The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.1 Primary Sources

Dedications to Elisabeth

- Descartes, René. 1644. Principia Philosophiae. Amsterdam: Louis Elzevir.

- Reynolds, Edwards. 1640. Treatise of the Passions and the Faculties of the Soule of Man. London: Robert Bostock.

Selected editions of Elisabeth-centered correspondence

- Blaze de Bury, Marie Pauline Rose Stewart. 1853. Memoirs of the Princess Palatine, Princess of Bohemia including her correspondence with the great men of her day. London: Richard Bentley, New Burlington Street.

- Descartes, René. 1989. Correspondance avec Elisabeth. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion.

- —. 1955. Lettres sur la morale: corréspondence avec la princesse Elisabeth, Chanut et la reine Christine. Paris: Hatier-Boivin.

- Foucher de Careil, Alexandre. 1862. Descartes et la Princesse Palatine, ou de l’influence du cartesianisme sur les femmes au XVIIe siecle. Paris: Auguste Durand.

- —. 1909. Descartes, la Princesse Elisabeth et la Reine Christine. Paris and Amsterdam: Germer-Ballière/Muller, 1879. New edition. Paris: Felix Alcan.

- Godfrey, Elizabeth. 1909. A Sister of Prince Rupert: Elizabeth Princess Palatine and Abbess of Herford. London and New York: John Lane.

- Neel, Marguerite. 1946. Descartes et la princess Elisabeth. Paris: Editions Elzevier.

- Nye, Andrea. 1999. The Princess and the Philosopher: Letters of Elisabeth of the Palatine to René Descartes. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- —. 2000. Elisabeth, Princess Palatine: Letters to René Descartes. Presenting Women Philosophers. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Petit, Leon. 1969. Descartes et la Princesse Elisabeth: roman d’amour vecu. Paris: A-G Nizet.

- Shapiro, Lisa. 2007. The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth and René Descartes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Other primary sources

- Adam, Charles. 1917. Descartes et ses amities feminines. Paris: Boivin.

- Adam, Charles, and Paul Tannery. 1897-1913. Oeuvres de Descartes. Eleven volumes. Paris: Leopold Cerf.

- Baker, L. M., ed. 1953. The letters of Elizabeth, queen of Bohemia. London: Bodley Head.

- Barclay, Robert. 1870. Reliquiae Barclaianae: Correspondence of Colonel David Barclay and Robert Barclay of Urie. London: Winter & Bailey.

- Benger, Elizabeth. 1825. Memoirs of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, Daughter of James I. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

- Bromley, George. 1787. A Collection of Original Royal Letters. London: J. Stockdale.

- Creese, Anna. 1993. “The Letters of Elisabeth, Princess Palatine: A Seventeenth Century Correspondence.” PhD diss., Princeton University.

- Descartes, René. 1657-67. Lettres de Monsieur Descartes. Paris: Angot.

- —. 1984–1991. The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, vol. I–III. edited by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothof, Dugald Murdoch, and Anthony Kenny. London: Cambridge University Press.

- —. 2013. Der Briefwechsel zwischen René Descartes und Elisabeth von der Pfalz. Hamburg: Meiner.

- de Swarte, Victor, and Emile Boutroux. 1904. Descartes, directeur spirituel. Correspondance avec la princesse Palatine et la reine Christine de Suéde. Paris: Félix Alcan.

- Gorst-Williams, Jessica. 1977. Elisabeth: The Winter Queen. London: Abelard.

- Great Britain Public Record Office. 1858. Calendar of State Papers, Domestic series, of the reign of Charles I. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts.

- Gummere, A. M. 1912. “Letter from William Penn to Elizabeth, Princess Palatine, Abbess of the Protestant Convent of Hereford, 1677, with an Introduction.” Bulletin of Friends’ Historical Society of Philadelphia 4(2), 82-97. Friends Historical Association. Retrieved December 2, 2017, from Project MUSE database.

- Hauck, Carl. 1908. Die Briefe der Kinder des Winterkönigs, herausgegeben und mit einer Einleitung versehen von Karl Hauck. Heidelberg: G. Koester.

- Hodgkin, Thomas. 1898. George Fox. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Hume, David. 1850. History of England. Six volumes. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Hutton, Sarah, and Marjorie Hope Nicholson, eds. 1992. The Conway Letters. Revised edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Huygens, Constantjin. De briefwisseling van Constantijn Huygens, (1608-1687), Vols. V – 28. Edited by J.A. Worp. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Rijks Geschiedkundige Publicatiën, 1916.

- Keblusek, Marika. 1997. The Bohemian Court in The Hague. Princely Display: The Court of Frederik Hendrik of Orange and Amalia van Solms. M. K. a. J. Zijlmans. The Hague: Waanders.

- Klopp, Onno, ed. 1874. Correspondance de Leibniz avec l’électrice Sophie de Brunswick-Lunebourg. Hanover: Klindworth; Londres: Williams & Norgate; Paris: F. Lincksieck.

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. 1926. Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe. Zweite Reihe. Philosophischer Briefwechsel. Berlin.

- Malebranche, Nicolas. 1961. Oeuvres completes de Malebranche. Paris: Vrin.

- Müller, Frederick. 1876. 27 onuitgegeven brieven aan Descartes, 336-9. De Nederlandsche Spectator. ‘S Gravenhage: D. A Thieme and Martinus Nijhoff.

- Penn, William. 1695. An Account of W. Penn’s travails in Holland and Germany Anno MDCLXXVII, 2nd corrected edition. London: T. Sowle.

- Robinet, André. 1955. Malebranche et Leibniz: Relations personnelles, 103-5. Paris: J. Vrin.

- Sophia (Electress, consort of Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover). 1888. Memoirs of Sophia, electress of Hanover, 1630-1680. London: R. Bentley & Son.

- Sorbiére, Samuel. 1660. Lettres et discours de M. de Sorbiére sur diverses matieres curieuses. Paris: Chez Francois Clousier.

- —. 1694. Sorberiana, ou bons mots, recontes agreables, pensees judicieuse et observations curieuses de M Sobiere. Amsterdam: George Gallet.

- Strachan, Michael. 1989. Sir Thomas Roe, 1581-1644: A Life. Salisbury: Michael Russell Ltd.

- Strickland, Lloyd, ed. 2011. Leibniz and the Two Sophies: The Philosophical Correspondence. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies.

- Verbeek, Theo, Erik-Jan Bos and Jeroen van de Ven, eds. 2003. The Correspondence of René Descartes 1643. Utrecht: Zeno Institute for Philosophy.

- Webb, Maria. 1896. The Fells of Swarthmoore Hall and Their Friends: With an Account of Their Ancestor, Annew Askew, the Martyr. A Portraiture of Religious and Family Life in the Seventeenth Century, Comp. Chiefly from Original Letters and Other Documents Never Before Published. Philadelphia: H. Longstreth.

- Worthington, John. Diary and Correspondence, edited by J. Crossley and R.C. Christie. Manchester: Chetham Society Remains, 1847-86.

- Schurman, Anna Maria van. 1652. Nobiliss. virginis Annae Mariae à Schurman. Opuscula Hebraea, Graeca, Latina, Gallica, prosaica & metrica. ex officina Joannis à Waesberge.

- —. 1998. Whether a Christian Woman Should Be Educated, edited and translated by Joyce L. Irwin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

3. Secondary Sources Guide

Because of her famous correspondence with Descartes, interpreters and scholars of Elisabeth’s life and thought have often placed her into a subsidiary position vis-à-vis the canonical French philosopher. Indeed, this occurred already during her own lifetime, as figures like Samuel Hartlib and Henry More described her as the “Cartesian Princess,” and it continued into the next century, when she was labeled the leaders of the “cartésiennes.” Her correspondence with Descartes is certainly a major source for our understanding of her ideas. But there are many other aspects of her life, including her correspondence with various other figures, and her actions during her time as the primary authority over the Herford Abbey, that transcend the standard characterization of her in relation to Descartes. Happily, the scholarly literature on Elisabeth as an important intellectual figure in her own right has been expanding in recent years; it was given a substantial boost by the publication of Lisa Shapiro’s edition of the complete correspondence between Elisabeth and Descartes. Shapiro treats Elisabeth as a philosopher with views of her own, and not merely as the critic of Descartes. There are also helpful online guides to Elisabeth’s life and the literature concerning it. These include the online entries by Rainer Pape, the director of Herford’s Municipal Museum, written in German; and Lisa Shapiro’s article about Elisabeth in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

References

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2002. Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pal, Carol. 2012. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pape, Rainer. 30 March 2004. “Elisabeth of Palatinate (1618-1680)”. Westfälische Lebensbilder. Web. Accessed June 30, 2017. http://www.lwl.org/westfaelische-geschichte/portal/Internet/finde/langDatensatz.php?urlID=1517&url_tabelle=tab_person

- Shapiro, Lisa, ed. 2007. The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- —. 2013. “Elisabeth, Princess of Bohemia”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), edited by Edward Zalta. Web. Accessed July 1, 2017. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/elisabeth-bohemia/

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

3.1 Secondary Sources

Selected secondary sources: metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of mind

- Alanen, Lilli. 2003. Descartes’s Concept of Mind. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Alexandrescu, Vlad. 2012. “What Someone May Have Whispered in Elizabeth’s Ear”. In Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy 4. Edited by Daniel Garber and Donald Rutherford. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Apostalova, Iva. 2010. “Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia and Margaret Cavendish: The Feminine Touch in Seventeenth-Century Epistemology”. Maritain Studies 26: 83–97.

- Ariew, Roger. 1983. “Mind-Body Interaction in Cartesian Philosophy: A Reply to Garber’s ‘Understanding Interaction: What Descartes Should Have Told Elisabeth’.” Southern Journal of Philosophy 21: 33-38.

- Bertoloni Meli, Domenico. “Caroline, Leibniz and Clarke.” Journal of the History of Ideas 60 (1999): 469-486.

- —. “Newton and the Leibniz-Clarke correspondence.” In I.B. Cohen and George Smith, editors. The Cambridge Companion to Newton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Boros, Garbor. 2003. “Love As a Guiding Principle of Descartes’s Late Philosophy.” History of Philosophy Quarterly 20: 149-163.

- Broughton, Janet, and Ruth Mattern. 1978. “Reinterpreting Descartes on the Notion of the Union of Mind and Body.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 16: 23-32.

- Cunning, David. 2007. “‘Semel in vita’: Descartes’ Stoic View on the Place of Philosophy in Human Life.” Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers 24: 165-184.

- Franco, A. B. 2006. “Descartes’ Theory of Passions.” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh.

- Garber, Daniel. 1992. Descartes’ metaphysical physics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- —. 1983. “Understanding interaction: what Descartes should have told Elisabeth.” Southern Journal of Philosophy 21 (Supplement): 15-32.

- Garber, Daniel, and Margaret Wilson. 1998. “Mind-Body Problems”. The Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, edited by Daniel Garber and Michael Ayers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harth, Erica. 1992. Cartesian Women: Versions and Subversions of Rational Discourse in the Old Regime. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hatfield, Gary. 1992. “Descartes’ physiology and its relation to his psychology”. The Cambridge Companion to Descartes, edited by John Cottingham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 335-370.

- Hayes, Julie C. 1999. Reading the French Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heil, John, and David Robb 2013. “Mental Causation”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), edited by Edward Zalta. Web. Accessed July 14, 2017. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mental-causation/

- Hutton, Sarah, 2005. “Women Philosophers and the Early Reception of Descartes: Anne Conway and Princess Elisabeth”. In Receptions of Descartes: Cartesianism and anti-Cartesianism in Early Modern Europe. Tad M. Schmaltz, ed. London; New York: Routledge.

- Jeffery, Renee. 2017. “The Origins of the Modern Emotions: Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and the Embodied Mind.” History of European Ideas 43: 547-559.

- Johnstone, Albert A. 1992. “The bodily nature of the self or what Descartes should have conceded Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia”. In Giving the body its due. Edited by Maxine Sheets-Johnstone. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 16-47.

- Lee, Kyoo. 2011. “‘Cogito Interruptus’: The Epistolary Body in the Elisabeth-Descartes Correspondence, June 22, 1645-November 3, 1645.” philoSophia: A Journal of Continental Feminism 1: 173-194.

- Lloyd, Genevieve. 1984. The Man of Reason: ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ in Western Philosophy. London: Methuen.

- Mattern, Ruth. 1978. “Descartes’s correspondence with Elizabeth: concerning both the union and distinction of mind and body”. In Descartes: Critical and Interpretive Essays, edited by Michael Hooker. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 212-222.

- Nadler, Steven, ed. 1993. Causation in Early Modern Philosophy: Cartesianism, Occasionalism, and Preestablished Harmony. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- Nye, Andrea. 1996. “Polity and Prudence: The Ethics of Elisabeth, Princess Palatine”. In Hypatia’s Daughters: Fifteen Hundred Years of Women Philosophers. Edited by Linda Lopez McAlister. Bloomington: Indiana Univ Press.

- O’Neill, Eileen. 1987. “Mind-Body Interaction and Metaphysical Consistency: A defense of Descartes”. Journal of the History of Philosophy 25: 227-245.

- —. 1998. “Disappearing Ink. Early Modern Women Philosophers and their Fate in History”. In Philosophy in a Feminist Voice: Critiques and Reconstructions, edited by J. A. Kourany. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- —. 1998. “Women Cartesians, ‘Feminine Philosophy’ and Historical Exclusion”. In Feminist Interpretations of René Descartes. Edited by Susan Bordo. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press: 232-257.

- Radner, Daisie. 1971. “Descartes’ Notion of the Union of Mind and Body”. Journal of the History of Philosophy 9: 159-171.

- Richardson, R. C. 1982. “The ‘Scandal’ of Cartesian Interactionism”. Mind 92: 20-37.

- Rozemond, Marleen. 1998. Descartes’s Dualism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- —. 1999. “Descartes on Mind-Body Interaction: What’s the Problem?”. Journal of the History of Philosophy 37: 435-467.

- Schiebinger, Londa. 1989. The Mind Has No Sex? Women in the Origins of Modern Science. Cambridge, MA; London, England: Harvard University Press.

- Schmitter, A. 2010. “17th and 18th Century Theories of Emotions”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), edited by Edward Zalta. Web. Accessed July 13, 2017. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/emotions-17th18th/

- Shapiro, Lisa. 1999. “Princess Elizabeth and Descartes: The Union of Soul and Body and the Practice of Philosophy.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 7: 503-520.

- Tollefsen, Deborah. 1999. “Princess Elisabeth and the Problem of Mind-Body Interaction.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 14: 59-77.

- Wartenburg, Thomas E. 1999. “Descartes’s Mood: The Question of Feminism in the Correspondence with Elisabeth”. In Feminist Interpretations of René Descartes. Edited by Susan Bordo. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- Wilson, Margaret. 1978. Descartes. New York: Routledge.

- Verbeek, Theo. 1988. Descartes and the Dutch: Early Reactions to Cartesianism (1637-1650). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Yandell, David. 1997. “What Descartes Really Told Elisabeth: Mind-Body Union as a Primitive Notion.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 5: 249-273.

Selected secondary sources: ethics and political philosophy

- Brown, Gregory. “[…] et je serai tousjours la mere pour vous. Personal, Political and Philosophical Dimensions of the Leibniz-Caroline Correspondence.” In Leibniz and his Correspondents, edited by Paul Lodge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Harth, Erica. 1992. Cartesian Women: Versions and Subversions of Rational Discourse in the Old Regime. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- —. 1999. “Cartesian Women”. In Feminist Interpretations of René Descartes, edited by Susan Bordo. University Park: Penn State University Press: 213-231.

- Levi, Anthony. 1964. French Moralists: The Theory of the Passions, 1585-1649. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Marshall, John. 1998. Descartes’s Moral Theory. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Mason, S.F. 1974. “Science and religion in seventeenth-century England.” In The Intellectual Revolution of the Seventeenth Century. Edited by Charles Webster. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Mesnard, Pierre. 1936. Essai sur la morale de Descartes. Paris: Boivin & Cie.

- Rodis-Lewis, Genevieve. 1957. La morale de Descartes. Paris: PUF.

- Schmaltz, Ted. (forthcoming). “Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia on the Cartesian Mind: Interaction, Happiness, Freedom”. In Feminist History of Philosophy: The Recovery and Evaluation of Women’s Philosophical Thought. Edited by Eileen O’Neill and Marcy Lascano. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Shapiro, Lisa. 2013. “Elisabeth, Descartes, et la psychologie morale du regret”. In Elisabeth de Boheme face a Descartes: Deux Philosophes. Edited by M-F. Pellegrin and D. Kolesnik. Paris: Vrin. pp. 155-169.

Selected secondary sources: biographical studies

- Aiton, E. J. 1985. Leibniz: a Biography. Bristol: A. Hilger.

- Gaukroger, Stephen. Descartes: an intellectual biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Hutton, Sarah. 2004. Anne Conway: a woman philosopher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marshall, R. K. 1998. The Winter Queen: The Life of Elizabeth of Bohemia, 1596-1662. Edinburgh: Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

- Morrah, Patrick. 1976. Elizabeth of Bohemia. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Goldstone, Nancy. 2018. Daughters of the Winter Queen: Four Remarkable Sisters, the Crown of Bohemia, and the Enduring Legacy of Mary, Queen of Scots. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Oman, Carola. 1938. Elizabeth of Bohemia. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Pal, Carol. 2012. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rait, Robert, Ed. 1908. Five Stuart princesses: Margaret of Scotland, Elizabeth of Bohemia, Mary of Orange, Henrietta of Orleans, Sophia of Hanover. Westminster: A. Constable.

- Zedler, Beatrice. 1989. “The Three Princesses.” Hypatia 4: 28-63.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

4. Teaching & Philosophy

Elisabeth as Philosopher

The question of how one might treat Princess Elisabeth as a philosopher is especially pressing. First of all, Elisabeth did not publish philosophical works of her own—we have only her correspondence to discover her ideas textually, and she decided not to allow Clerselier to publish her side of the correspondence with Descartes when he gathered the latter’s letters for publication (Shapiro 2007, 2-8). Although early modern correspondence was usually a rather public affair – copies of letters often circulated widely, and were often published right after someone died, such as Clarke’s correspondence with Leibniz – Elisabeth decided, for whatever reason, to keep her correspondence with Descartes more or less private. This does not mean that we should not look to her correspondence to learn about her ideas; it simply means that other aspects of her life take on greater importance. We may wish to see if we can find other aspects of her life when looking for her ideas, whether philosophical or otherwise. And second, unlike many of the early modern philosophers who constitute the traditional canon, she was an important political and religious figure in her day and hailed from one of the most important royal families in all of northern Europe (including England). These two facts combine together to make her actions especially significant, and an especially intriguing place to look for her philosophical views.

Since Elisabeth did not publish anything during her lifetime, and did not write essays or manuscripts that survive, interpreters of her thought have focused primarily on her extant correspondence to determine her views on various philosophical questions. And her correspondence with Descartes is undoubtedly the most important source within that domain. The publication in 2007 of Lisa Shapiro’s complete edition of her correspondence with Descartes transformed our understanding of Elisabeth’s ideas, and helped to correct the fact that many editions of Descartes lacked her side of the correspondence altogether (Shapiro 2007). The discussion of her correspondence with Descartes can be found in section 5.1 However, there is another, less explored, avenue for understanding Elisabeth’s intellectual life and her philosophical ideas in particular. Because she was a figure of some authority during her time at Herford Abbey, she was unusually well placed to put various ideas into action. This leads us to ask: what do Elisabeth’s actions tell us about her philosophy? Answering that kind of question requires us to think about Elisabeth in an especially broad way. Suppose one has a case of a political figure, one who corresponded with various others, as one would expect, but who never published a work under his own name. We might look at the actions that the figure took, interpret them within their historical context, and see if we could derive from them a coherent political philosophy, or a coherent moral position, etc. Were the figure’s actions chaotic, or were they systematic? Did the figure explicitly or implicitly regard his own policies, actions, etc., as expressive of some coherent ideology or position? Or would the figure have simply regarded herself as making whatever decisions she could within certain constraints without seeing them as expressive of any coherent view? Of course, it is open to us, as readers of history and as readers of philosophy, to interpret things differently from the actors themselves. We might think that all things considered, the actions and policies of such a figure are in fact expressive of a coherent ideology, even if the figure herself never held that view, or even went so far as explicitly to deny it.

In order to pursue this line of thought, however, some important historical facts must first be acknowledged. Elisabeth’s time at the Abbey in Herford is well known, but it is often misunderstood. She was not merely in a position of authority in a religious institution; she was a political figure in an important sense as well. The facts are roughly as follows: For some time, there was an extensive discussion about whether Elisabeth could become effectively the second person in charge at the Abbey in Herford; it was a political as well as a religious question, and involved many important figures. With support from various parties, Elisabeth was elected to the position of second in command in May of 1661. She would eventually rise to become the Abbess herself, a position she held from March of 1667 until her death in 1680. Herford Abbey was in Lutheran territory, of course, but it was actually run by Calvinists beginning in the 17th century. It was founded in the 9th century, as a Catholic institution, and during the early years of the Reformation it was no longer affiliated with Catholicism. Beginning in the early 17th century, it became associated with Calvinism, or at any rate was run by women who were Calvinists. Most importantly, as Creese shows in detail (1993), the Abbey was in fact an independent institution: because of various political and religious changes in Prussia at that time following the end of the Thirty Year’s War, the Abbey was officially granted “imperial independence” (Reichunmittelsbarkeit) in the Peace of Westphalia. That fact meant that the Abbess reported only and directly to the Emperor himself. She was independent of any local authority. Signifying this status, the Abbess actually held the title of “Princess and Prelate of the Holy Roman Empire” (Creese 1993, 180-82). As William Penn noted, after a visit to Herford in 1671, Elisabeth governed “a small territory,” but in his view, she was suited to govern a larger one. The question is, what kind of governor was she?

Elisabeth did not use her position of authority merely to look after the Abbey and its inhabitants; she chose to take several courageous actions. After pleas from her old mentor and friend, the philosopher Anna Maria van Schurman, she agreed to provide a place of refuge for the Labadists, the followers of the radical theologian Jean de Labadie. She also provided refuge for Quakers, who were connected with William Penn, Robert Barclay and others. Elisabeth’s sister said that she was “the refuge of all the oppressed” (Pal 2012, 254-55). These acts were more courageous than is typically recognized: the followers of Labadie, for instance, had been accused of murder in the past, which resulted in a riot when they fled to Amsterdam (Creese 1993, 188). That happened despite the fact that Amsterdam was considered a free-thinking city in one of the most liberal countries in all of Europe in that time; by 1660, for instance, there were Quaker meetings in many Dutch cities, including Amsterdam. The Dutch situation contrasted sharply with the persecution faced by Quakers in England; the English parliament passed a series of anti-Quaker measures beginning in 1662. Indeed, as Barclay noted in a major work in 1678, members of his movement were called Quakers “in scorn,” so there was a kind of persecution even in the name used to describe them. Hence it was at considerable personal risk, and at some risk to her institution, that Elisabeth invited not only her old friend van Schurman, but also all of the Labadists, to take refuge in the Abbey. Elisabeth herself made it perfectly clear that what the Labadists were seeking more than anything was their own “freedom” to worship, to practice their religion without interference from the Emperor or other authorities. Word of their arrival at Herford spread quickly: it was obviously seen as a major event. Indeed, Leibniz learned of van Schurman and the Labadists’s arrival in Herford soon after it happened (Creese 1993, 190-3). But the townspeople in Herford and the environs did not support Elisabeth. They objected vociferously to the arrival of the religious refugees. After threats of violence against the community were made, and after many negotiations occurred, Elisabeth personally travelled to Berlin in early 1672 to ensure that her jurisdiction over the Abbey and all of its inhabitants would not be challenged further by the local people (Creese 1993, 195-6). This was no mean feat: Herford is roughly 375 kilometers from Berlin, and the roundtrip took her several months to complete. She prevailed.

This first aspect of Elisabeth’s life leads to an initial conclusion. She was not merely open minded about religion – a very sensitive topic, of course, in a century in which religious strife, and religious wars, were rampant – but chose actively to promote religious freedom. She put her institution and even herself at considerable political risk in order to protect the religious freedom of a radical, hated minority. One can imagine that a figure like Elisabeth did more for religious freedom during her life than many a philosopher who wrote a treatise promoting it. This is not to denigrate more purely intellectual pursuits, it is merely to emphasize the importance of the actions she took during her time as the Abbess.

There is a second aspect of Elisabeth’s life that enriches our understanding of her attitude toward religious freedom. Her life was marked by an intense and intellectually rich relationship with religion in another way. She was born into a very prominent Protestant family. Both early in her life and towards its end, she came under significant pressure to convert to another strand of Christianity. In each case she refused, despite the immense pressure. As a young woman, she had the opportunity to become a member of the Polish royalty through marriage, if only she would convert to Catholicism. She refused to convert, despite the potential personal benefit she would have derived from a conversion (Pal 2012, 50-1). The pressure to convert to Catholicism resumed later in her life: no less a figure than Father Malebranche himself seems to have urged her to convert to Catholicism (Creese 1993, 206). Late in life, she came under significant pressure once again, this time to convert to Quakerism, which was a young, radical movement at the time. Quakers were sometimes considered as radical politically as other English groups, such as the Diggers, because they each advocated an end to religious and social hierarchies (Mason 1974, 211). The husband of Anne Conway, who bemoaned her conversion to the Quaker faith, said that their leaders’ main goal was to “turn out the landlords” (Hutton 2004, 178). With respect to the Quaker faith, Elisabeth was under pressure from one of the most prominent British Quaker leaders, Robert Barclay. Once again, she refused to convert, despite her decision to provide refuge to Quakers fleeing persecution in England. She clearly thought from an early age that a conversion should reflect one’s personal conviction – perhaps one can see this notion as a Protestant trope – and should not be undertaken merely to benefit oneself or one’s family, even when the fate of empires is at stake, as it was in her case. This attitude is apparent in her correspondence with Barclay who, like William Penn, sought Elisabeth’s endorsement of their new Quaker movement. Barclay tried to persuade Elisabeth to join their group by noting that Anne Conway had recently begun to adopt Quaker ways (see Pal 2012, 262). Elisabeth replied sharply that she respected Conway’s decision, but could not follow it: “The Countess of Conoway doth well to go on the way she thinks best, but I should not do well to follow her, unless I had the same conviction” (quoted by Creese 1993, 236, who corrects a misprinted date in the Barclay correspondence). Barclay’s attempt to convert Elisabeth to Quakerism was problematic on a number of fronts. For one thing, like Elisabeth, the leaders of the Abbey had been Calvinists for some time, and he obviously did not have a high opinion of Calvinism: he proclaimed in his treatise An apology for the true Christian divinity that Calvinists, along with “Papists, Socinians and Arminians,” have slighted the “light of nature.” He regarded the latter as the sole means of achieving salvation. It is bad enough for Barclay to list the Calvinists along with the followers of the Pope, but the Socinians were widely considered to be heretics (Barclay 1678, entry for “light of nature” in the volume’s alphabetical “table of the chief things” at its end; an earlier version was published in 1676 and known to Elisabeth). Barclay may have underestimated the extent to which Elisabeth would have been wary of attempts to convert her with an eye towards providing a political or civil advantage for some fledging movement. She was willing to provide refuge to persecuted religious figures, but not to convert to their cause. In the end, although Elisabeth sought to provide both the Labadists and the Quakers with a refuge from persecution, and although she used her authority to promote tolerance and religious freedom, even at considerable personal risk, Barclay, Malebranche, and all others failed to convince her to convert. Unlike tolerance and freedom, conversion in her mind required a certain kind of conviction that she lacked.

These two aspects of Elisabeth’s life combine to form a compelling picture of her conception of, and support for, religious freedom. She did not merely trumpet the common early modern principle, for instance, that the members of the various Protestant sects ought to be free to practice their religion, and not face persecution for failing to adhere to the older and more powerful Catholic tradition emanating from Rome. She also extended this principle to cover the members of a number of much more radical sects. Many early modern thinkers would not have extended the principle so far. In addition, there is an important sense in which Elisabeth sought to protect her own freedom in the religious realm by refusing to convert to Catholicism on several occasions, and later, refusing to convert into the Quaker movement. In each case, she sought to protect her view that one’s religious faith must be a matter of one’s convictions. One might take the intersection of these two ideas and state a more general principle: for Elisabeth, one’s religion ought to be an expression not merely of one’s own tradition and heritage—it ought to be a considered expression of one’s personal convictions, even if those convictions contravene prevailing ideas amongst one’s family members or compatriots, and even if those convictions put one at a considerable social, political or economic disadvantage. In tandem, Elisabeth’s actions to protect religious freedom at Herford Abbey indicate that she had a political philosophy according to which institutions with the relevant authority ought to protect religious freedom, even if it means risking their relatively peaceful existence under the prevailing authorities at the national or imperial level. Given that Elisabeth lived in an age where religious strife and war were rampant, it is not a stretch to say that the broad question of religious freedom was one of the dominant issues in political philosophy at that time, perhaps even the dominant issue. In that sense, even if Elisabeth never wrote a treatise on religion, as Spinoza did, or one on political philosophy, as Locke and Hobbes did, she spent her entire life expressing her strong views concerning the way in which political institutions ought to stand for religious freedom, and indeed, the freedom of even the most radical thinkers of the day.

Scholars and students alike are not accustomed to investigating the lives of the philosophers they study. After all, the lives of most early modern philosophers tell us little about their ideas. A classic example would be Kant, who never strayed far from Konigsberg – he may have left town on occasion and entered the surrounding forest – and who led a rather simple life as a bachelor, tutor and professor in a coastal town on the far reaches of the Prussian empire. It can be amusing to think of him taking his daily constitutional at a particular hour – except for once, supposedly, when he received Rousseau’s Émile in the post – but his life and the personal choices he made shed almost no light at all on his philosophical views. If only one could understand the Critique of Pure Reason by studying daily life in Konigsberg! This example is rather extreme, but something similar can be said of many of the early moderns. Consider Descartes: unlike Kant, he left his home in France and actually lived much of his life in Holland; he met many intriguing people throughout his travels, and in his early years, he may have seen several battles as part of the fighting happening then. He ended up in Sweden, where he famously died in the care of Queen Christina, probably of a pneumonia caused in part by the rigorous schedule he was asked to keep. These events give us a picture of Descartes the person, but they tell us little about his philosophical views. Princess Elisabeth is importantly different from these figures. That is not merely because she never published a text like the Meditations or the Critique, but because she was in a position to express her own views about such crucial topics as religious freedom through her actions on behalf of an independent religious and political institution. In the very least, one hopes that the discussion above is sufficient to show students and scholars that Elisabeth’s actions as Abbess merit further study.

But that idea leaves us with an important question. How should we categorize Elisabeth? She was a member of European royalty, a political figure, a writer, an intellectual, a philosopher, etc. Which category fits her best? It is pretty clear that she does not sit happily in the category princess because unlike most people who fit that role in the early modern period, she was also an intellectual of considerable stature. Calling her the “Cartesian Princess,” as Henry More did, makes her subordinate to Descartes of course, but also misses many of the key events in her life. She doesn’t really fit the category of the learned woman – they were called “gelehrte Frauen” in German-speaking Europe – all that well, because unlike women in that category, she wasn’t merely learned in various sciences and in philosophy, she was also in a position of political and religious authority, and therefore able to put some of her ideas into action. She also doesn’t really fit the category of the philosopher, because unlike most of the early moderns, she was not merely in a position to develop her ideas, but actually to implement them through her own authority and actions on behalf of others. Perhaps the category for Elisabeth doesn’t quite exist. It does not seem like a stretch to say that she was unique. Plato famously wrote of Philosopher Kings; we cannot quite say that Elisabeth was a Philosopher Queen, but she was close.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5. Correspondence Guide

In the early modern period, correspondence between philosophers and intellectuals was a primary means of communicating ideas and engaging in debates. Although many philosophers also chose to write essays, publish treatises, etc., nearly every major thinker in the period also engaged in correspondence. Whereas some figures were extremely prolific correspondents—one thinks of Leibniz or of Voltaire—others were less concerned with writing letters, but correspondence played an important role for every early modern intellectual. For intellectual women, letters often played an outsized role in their lives because they were typically excluded from institutions of learning, including colleges, universities and scientific academies, and were often not in a position to publish works under their own name. Due to the importance of correspondence, however, it was possible for an intellectual woman to have a significant influence on philosophy and science solely through her personal connections and her letters. Elisabeth was such a figure. Because she never published a work of her own, Elisabeth’s correspondence is unusually important for understanding her philosophical views and her intellectual life more broadly. Happily, she corresponded with a very wide range of figures, from religious leaders like William Penn to philosophers like Descartes to fellow intellectual women like Anna Maria van Schurman. Indeed, Elisabeth’s intellectual network, which she fashioned throughout her adult life through careful maintenance of various kinds of relationships, was vast. It is not an exaggeration to say that this network included a veritable “who’s who” of European intellectual life in the late 17th century. In this section, we catalogue all of her known correspondents.

Spreadsheet overview: Excel file

References

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2002. Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Godfrey, Elizabeth. 1909. A Sister of Prince Rupert: Elizabeth Princess Palatine and Abbess of Herford. London: John Lane.

- Nye, Andrea. 1996. “Polity and Prudence: The Ethics of Elisabeth, Princess Palatine”. In Hypatia’s Daughters, edited by Linda Lopez McAlister. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Pal, Carol. 2012. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shapiro, Lisa, ed. 2007. The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5.1 Elisabeth-Descartes Correspondence

Elisabeth’s most famous correspondent is certainly Descartes. Her correspondence with him is extremely wide ranging. Although it is most famous for her criticisms of mind body dualism and her formulation of the mind-body problem, the parties also discuss a huge range of other issues, including Machiavelli’s The Prince; Elisabeth’s health; Descartes’s understanding of the passions; questions in political philosophy; the views of Descartes’s former disciple Regius, who had recently published Fundamenta physica when they corresponded; and so on. Descartes’s correspondence with Elisabeth was especially personal, even intimate, involving not only unusually detailed explanations of his views, but also the only known reference to his mother (Gaukroger 1995, 385) in all of Descartes’s letters, which take up several volumes of the Oeuvres complètes edited by Adam and Tannery. For the first time, Elisabeth’s letters to Descartes have been digitized and are now available at the New Narratives website.

Elisabeth told Descartes that she wished for her letters to be private. But we have to be cautious with that notion. Even if the letters were not published, that does not mean that no one else besides the two correspondents had any notion of what they were discussing over those years. Indeed, at least some of the letters were sent via a third party, a man named Pollot, and on at least one occasion, Descartes even sent a letter to Elisabeth to Pollot with a separate cover letter discussing the question of whether he had provided a geometrical problem to Elisabeth that was too difficult (Creese 1993, 78-80); he needn’t have worried, because she solved the problem elegantly soon thereafter, as Descartes himself recognized. Later on, after Elisabeth had left the Hague to return home to Germany, her sister Sophie acted as an intermediary for some of her exchanges with Descartes. So, although the correspondence was not public, it was not entirely private either, at least in the sense that it was not carried out in strict secrecy. There is also the question of whether Elisabeth or Descartes discussed their letters with anyone else during or after the correspondence. Finally, both Elisabeth and Descartes seem to have been aware that their letters might have been subjected to scrutiny by outside parties, as evidenced by their discussion of whether they should write to one another in code. Given that Elisabeth was at the heart of a very important political family in northern Europe, one can imagine that spies may have wished to see if her correspondence could shed any light on her or her family’s plans – for instance, during the long negotiations that led to the Treaty of Westphalia, which ended the thirty years of war and left many German lands in ruins and poverty. Right after Descartes’s death in Sweden in 1650, Chanut wrote to Elisabeth with the news, and requested that she allow him to publish her correspondence with the now deceased philosopher. Despite his entreaties, she never gave permission for her side of the correspondence to be published and thereby made completely public. This may have reflected the fact that by the time of Descartes’s death, she was no longer in exile – she returned to Heidelberg in 1651 – and was well aware that her views about such things as political authority and the ideas of Machiavelli might interest opponents of her family and their return to the Palatinate after the end of the Thirty Year’s War.

Her philosophical disputes and discussions with Descartes interact in certain respects with her religious faith, which latter was important throughout her life in myriad ways. For instance, as a Calvinist, she would not necessarily have believed in free will in any obvious sense; she would have thought presumably that each person is subject to the Calvinist doctrine of “predestination,” according to which God has chosen a future path for each human soul, ensuring that each of us will eventually be sent to heaven or to eternal damnation. And that predestination does not reflect the actions that we take during our lives, since it is predetermined by God before that life takes place. So there is at least one sense in which free will is a foreign concept in this context: our decisions and choices and actions do not have any bearing on our moral futures. Of course, we might still have free will in a more technical or limited sense: it might still be the case that our will is not determined, for instance, by anything external; but one of the primary motivations for thinking about free will, namely, that our choices and decisions and actions will have at least some bearing on our moral future, is removed. And Elisabeth was aware of these nuances, discussing them with Descartes in some depth.

Mind-Body relation

One of the most important aspects of Elisabeth’s famous objections to Descartes is that she helped to formulate the mind-body problem, not by using some general philosophical move, but by specifically reflecting the kind of mechanist thinking about causation within nature that was championed by Descartes, and with which she herself agreed. For a mechanist philosopher, all natural change involves contact between material bodies, whether macroscopic bodies like the earth or the moon, or the microscopic constituents of those bodies, the particles that make up everything in the material universe. If nothing can occur within nature unless such contact between bodies occurs, Elisabeth infers, then Descartes has a rather specific problem. For Descartes, the body can of course be in contact with things, since it is material – he would say, it is a res extensa, an extended thing, a substance whose essence is extension – and so there is no problem in understanding how the body might cause things to happen, as when, e.g., I hold a pencil and move it across the page. So far, the mechanist theory of causation within nature is satisfied. But according to Descartes, the mind is radically different from the body: whereas the body is essentially extended, the mind is essentially thinking – it is a res cogitans, a thinking thing or substance with the essence of thought – and what is more, the mind is not extended at all. The mind is not material. Since the mind is not extended or material, that is, since the mind is not a spatial thing like the body is, the problem is that we cannot conceive of how the mind could be in contact with anything. That is a general problem. The specific version of that problem is that we cannot conceive of how the mind can be in contact with the body. How can the mind causally influence the body – as it certainly seems to do all the time, at least as we experience things – without being in contact with it? To make matters worse, it is not as if the mind is simply a bit too far away from the body, as when my pencil is lying on the table across the room and I can’t quite reach it. Instead, from Descartes’s point of view, the mind isn’t located anywhere. So the mind isn’t close or far away from the body – those predicates don’t apply to the mind at all, they apply only to material things. So Elisabeth concludes: it is entirely mysterious how any kind of mechanical causal relation could occur between the body and the mind, since they cannot, even in principle, be in contact with one another. This is important, because as Elisabeth and Descartes knew perfectly well, there were all sorts of other concepts and theories of causation in the period that could be relied on in this instance (for instance, Aristotelian-inspired theories of the four causes). But what Elisabeth very effectively shows is that for Descartes, who was a committed mechanist, and who thought that all causation within nature was some kind of efficient causation, which had to involve contact between the causal relata, the result of saying that the mind is a non-extended thing and therefore located nowhere is that it now looks like the mind is causally excluded from the world. The mind cannot be in contact with anything, so it cannot cause anything to happen in nature, whether to the body or to anything else! In a way, we can see that Elisabeth is posing a kind of dilemma for Descartes here: either one can give up on the idea that the mind is non-extended and located nowhere, or else one can give up on the mechanical philosophy. Neither Elisabeth nor Descartes wanted to give up on the mechanical philosophy, for it was one of the most fundamental developments of the new science. Moreover, that perspective would eventually find support from nearly every major philosophical figure in the period, from Galileo to Boyle to Descartes to Locke to Leibniz to Huygens, etc. The sensible way out of the dilemma, then, would be to rethink the notion of the mind. What minimal reconstruction would be required in order to solve at least Elisabeth’s formulation of the mind-body problem? One would have to say at least that the mind is in fact located somewhere, that it is extended. (As it turns out, that is precisely the view that Henry More develops in some depth after a rigorous correspondence with Descartes in 1648-49, and More’s view, in turn, had a profound influence on a young Isaac Newton.) As Lisa Shapiro helpfully notes, it looks like Elisabeth is beginning to embrace that philosophical position in her correspondence with Descartes, arguing that the mind ought to be conceive of differently than the picture we find in Descartes’s Meditations (1641) and in his other works (Shapiro 2007, 41ff). Of course, merely saying that the mind is extended and therefore located somewhere doesn’t explain exactly how it causally interacts with the body. But it does remove one mystery: at least a mechanical philosopher does not need to contend that such a causal interaction is impossible because there is a lack of contact. Two extended things with locations can be in contact, at least in principle, even if we still do not really understand the details of that contact.