Anna Maria van Schurman

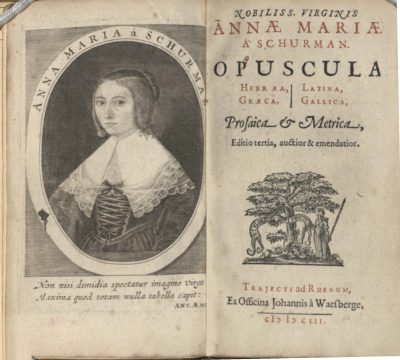

“Here only half of the gifted young woman is portrayed / for no frame can completely contain her.”– Antonius Aemilius, in Opuscula by Anna Maria van Schurman (1652 and 1749, frontispiece), trans. Pieta van Beek (2010, 96).

There is no more fascinating figure in early modern philosophy than the Dutch polymath Anna Maria van Schurman. A figure of renowned learning, an inspiring linguist who learned more than a dozen ancient and modern languages, van Schurman would have been a remarkable intellectual at any point in European history. The fact that she was a woman living in northern Europe in the early 17th century, a time when women were not only officially excluded from colleges, universities and intellectual academies, but also a time when they were rarely given any formal education at all, makes her all the more remarkable. She was a genius and recognized as such in her day. However, in other respects, van Schurman defies easy categorization. Textbooks concerning the history of science and the history of philosophy in early modern Europe are full of recognizable characters. There are the “schoolmen” and the “doctors of philosophy” promoting the traditional, Aristotelian-focused ideas promulgated throughout the colleges of early modern Europe. And then there are the radical figures who challenged the Aristotelians—the novatores or “moderns”—who made history. They were led by figures who quickly became famous for their anti-Scholastic methods and ideas, people like Galileo in Italy, Bacon in England, and Descartes in France and Holland. In a deep sense, van Schurman does not fall into either camp. That is not because she lacked views about Scholasticism and the various modern challenges to it. On the contrary, she expressed those views in depth in correspondence with various figures in her day. Rather, she charted her own unique path. In terms of her method, she displayed strong sympathies for Scholasticism, which stood in stark contrast to her friend Princess Elisabeth, who was more sympathetic to modern methods such as those of Descartes (Broad 2002, 17-19). But in terms of van Schurman’s ideas, she articulated a series of arguments in favor of women’s education that were equally challenging to the orthodoxy of European institutions at the time and to the moderns who sought to reshape those institutions in their own image. One is tempted to say that she put new wine in old bottles. But that old trope does not fully capture her unusual approach. In following a Scholastic method, especially in her famous Dissertatio, described below, she deployed an approach that would have been welcome to many of her interlocutors and certainly well known by the moderns who sought to challenge it. But in deciding to employ that method to endorse a conclusion about women’s education that was a serious challenge to nearly every male intellectual figure in Europe at that time, van Schurman greatly enriched the philosophical conversation of her day. Her work helps to underscore a profound fact that is easy to ignore. Despite their attempts to shake the very foundations of knowledge; despite their challenge to the orthodoxy of the schools throughout Europe in their day, the great “moderns” like Bacon, Descartes, Galileo, and Newton did nothing to challenge the prevailing gender norms governing philosophy and education in the 17th century. Their radical agenda, which eventually did overturn an intellectual regime that had prevailed for centuries, stopped at gender’s door. In that sense, the seemingly conservative and traditional Anna Maria van Schurman was perhaps more radical in her conception of education than the greatest thinkers of her age.

Van Schurman defies categorization in other ways. Renowned for her unmatched ability to learn both ancient—e.g., Hebrew, Greek, Latin—and modern—e.g., English, French, German—languages, she was also a poet, a philosopher, an embroiderer, and a painter. She made numerous striking self-portraits over the course of her career. In addition, her early years as a Dutch writer and intellectual figure of great fame were followed by her final decade in which she relinquished her worldly belongings in order to become the co-leader of a radical religious group associated with the French Protestant theologian and orator Jean de Labadie. In her early life, she was an inspiration and mentor to many men and women, including most prominently Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, and a challenging interlocutor for many others, including most prominently Descartes. In her later life, she was an inspiration and mentor to many people who sought a new form of religious life, including most prominently the famous Quaker William Penn. Although some accounts portray van Schurman rather simply as a convert to Labadie’s theology, after Labadie’s death in 1674 she became a recognized leader of the movement and was sought out by influential figures like Princess Elisabeth and Penn for her thoughts about pressing religious issues at the time. In that sense, perhaps what most unites the various stages of her life is that many people in northern Europe, both the famous and the common, sought her out for her learning, her wisdom, her advice, and her leadership. She did not take her responsibilities lightly: she often expressed some trepidation about her increasing fame, and she was far from a self-promoter. Nonetheless, the historical record is replete with examples of people seeking her out for advice throughout her long life. For all of these reasons, her fame as an intellectual figure and scholar was “unprecedented” in this period (Pal 2012, 56).

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Anna Maria van Schurman was born in Cologne in 1607 to a family that had fled Antwerp during the last century and that was part of a Calvinist minority. They later settled in Utrecht in 1615, where she would spend her early years. The fact that she was from a family of religious exiles may have helped to shape important events later in her life. Early on, she demonstrated remarkable intellectual abilities, learned many languages, and developed a knack for philosophical argumentation. Her father taught her French, and when he noticed that she was correcting the Latin used by her brothers in their own lessons, he let her join their sessions. He then introduced her to classic authors like Seneca and also to Holy Scripture (Irwin 1989, 178). Unlike so many intellectual women in early modern Europe, her talents were recognized early. They were encouraged by many men and women in her milieu, and before long, she had achieved a level of fame rarely seen in this period of European history. Perhaps the most famous episode of her early life was her invitation in 1636 to deliver a Latin ode on the occasion of the opening of a new university in her home town of Utrecht. The beauty of her Latin oration quickly increased her fame, but in a sign that van Schurman was no ordinary Scholastic thinker, she challenged the professors at the new university to admit women students. Although her pleading in this case fell on deaf ears at an institutional level, van Schurman was personally invited to attend lectures at the new university. However, during the lectures she had to remain behind a screen, lest her presence disrupt the male audience (Larsen 2016, 275)! The ode and her status as the first woman in European history to attend any university or college greatly increased her renown. Already in May of 1638, Marin Mersenne, one of the most famous philosophical interlocutors and correspondents of the century, wrote that “she deserves to be among the illustrious women” (Larsen 2016, 49-50).

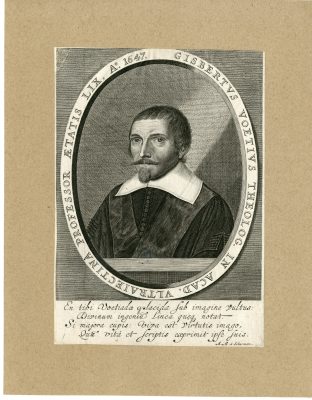

Amazingly, the tale of van Schurman listening to lectures from behind a screen circulated widely among Europe’s intellectual elite. Even Descartes mentions it in a letter to Regius, one of the most famous early Cartesians, during the summer of 1640. In an ironic twist, the lives of Descartes, Regius, van Schurman and her old Utrecht teacher Voetius were intertwined in a philosophical dispute. In June of 1640, Regius proposed a public discussion with Voetius in which they would argue their positions on a series of Cartesian ideas, including the circulation of the blood, a recent discovery by Harvey prominently endorsed by Descartes. The struggle between the two became quite personal and vicious, and eventually, Voetius was able to have Cartesianism banned from the university in Utrecht (Vrooman 1970, 150-66). It was in the midst of the early part of this intellectual debate that Descartes wrote to his young follower Regius from his home in Leiden, informing him that he would be happy to support him by traveling to Utrecht. He then joked that he could hide behind van Schurman’s screen in order to listen to the debates about his ideas at the university (see AT III: 70). Joking aside, Descartes did not take up van Schurman’s cause by arguing that women ought to be given a chance at an education at Dutch universities in this time. He complained to his friend Marin Mersenne in a letter from November 1640 (AT 3: 230-31) that he found Voetius to be very annoying and that the theologian had ruined van Schurman’s intellectual path by convincing her to focus on nothing but theological questions (see also Gaukroger 1995, 358-59). This difference in their approaches to theology would resurface when Descartes met van Schurman in person years later. [In their translation of this letter to Mersenne, Cottingham et al. (1991, vol 3: 156) misattribute her date as “Anne-Marie de Schurman (born 1612)”.]

Van Schurman’s early failure to convince the leaders of the new university in Utrecht to admit women did not deter her from pursuing that topic more substantially. In fact, she decided to make it one of her most significant intellectual pursuits. She began by engaging in an extended debate through extensive correspondence with the theologian André Rivet (see Clarke 2013, 94-108) just after delivering the ode in Utrecht. In 1637-38, Rivet and van Schurman exchanged courteous and respectful letters, but clearly disagreed with one another on the question of whether women ought to be afforded an education in the arts and sciences. Rivet seemed keen to limit the option of an education to certain special exceptions, such as van Schurman herself, a person he obviously greatly admired. He insisted that most women, especially girls and married women with various obligations, were in no position to receive a proper education, and he warned her against implying that women were superior to men. Van Schurman’s reply remained cautious and cordial, but she firmly argued again that education should not be restricted in the way that Rivet suggested. Instead, she thought, as long as girls and women did not shirk any of their social obligations—e.g., those undertaken through marriage—then they ought to be afforded a proper education. The lack of educational institutions, including colleges, that were open to women should be no impediment, van Schurman argued, because women could receive an education through home tutors. This idea obviously reflected her own early experience, but it may also have been an expression of a pragmatic approach to the problem at hand.

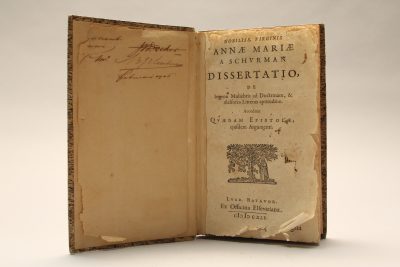

Rather than heed Rivet’s warnings and treat this highly controversial topic only in private correspondence, van Schurman took the courageous step of deciding to articulate her views for the public. She was also pressed into a somewhat rushed publication because in 1638, an unauthorized version of what would become her famous Dissertatio on the education of women was published in Paris (Larsen 2016, 186). The Paris edition, which appeared in Latin, was riddled with errors, so van Schurman published an authorized, corrected version with the famous Dutch publisher Elzevier in Leiden in 1641. This version, A Dissertation on the Capacity of Women for Education, greatly increased van Schurman’s fame. It was published in a French translation in Paris in 1646, under the title Question celebre, and was translated into English by the vicar and teacher Clement Barksdale and published in London in 1659 under the title The Learned Maid (Larsen 2016, 186). There have also been two modern English translations (Irwin 1998 and Clarke 2013). The publication of the Dissertatio in Latin, and its circulation in two vernacular languages, enabled van Schurman to accomplish two goals: first, the text allowed her to express her views in considerable depth, which correspondence generally prohibits; and second, it allowed her to expand her initial thoughts from her correspondence with Rivet into a properly formulated philosophical treatise (see “Section 4. Philosophy & Teaching” below for details).

Descartes’s joke that perhaps he should stand behind van Schurman’s screen in the lecture hall in Utrecht to listen to debates about his ideas was not his only encounter with the young Dutch polymath. Near the end of Descartes’s life, he met with van Schurman and discussed at least one important theological issue, the interpretation of the Book of Genesis. Unfortunately, scholarship on Descartes has been misleading on this point. The famous critical edition of Descartes’s Oeuvres edited by Adam and Tannery incorrectly identifies this important personal meeting between Descartes and van Schurman as having occurred sometime around 1640 (AT 4: 700-01). As evidence, the editors cite a number of letters among Descartes, Mersenne and Regius in 1640 and 1641, the letters that discuss Voetius’s supposedly negative influence on van Schurman, her genius, her screen for listening to lectures, etc. (see AT 3 71 note B; AT 3: 231). In addition to their discussion of van Schurman, Descartes also informs Mersenne in 1641 that in an effort to think about how his method of philosophizing could “accommodate” theology, he had thought about the interpretation of the first chapter of Genesis, an issue he later discussed with van Schurman. The story of Descartes’s final encounter with van Schurman, in which he chastised her for reading the Bible in Hebrew, and in which she was shocked and appalled by his impious attitude toward Holy Scripture, has circulated widely. Every Descartes scholar may encounter this episode easily because it is described in depth through a long quotation from the “Life of Jean Labadie of 1670” to be found in AT 4: 700-01. In fact, Adam and Tannery, the editors of Descartes’s Oeuvres, were not quoting directly from that late 17th century text, but rather from another text that describes Descartes’s relation to yet another famous 17th century woman, Princess Elisabeth [Foucher de Careil, Descartes et la Princesse Elisabeth (Paris, 1879), pages 150-52, which is apparently based on the Vie de Jean Labadie of 1670. The episode can also be found in Gustave Cohen, Écrivains français en Hollande dans la première moitié du xviie siècle (Paris 1920), pages 536-38].

However, as the primary accounts from the period indicate, Descartes’s fateful meeting with van Schurman actually occurred in 1649, when he was traveling to Sweden to sit in the court of Queen Christina. On his way to Sweden, Descartes stopped in Amsterdam to visit his publisher (Rodis-Lewis 1992, 48) and also stopped in Utrecht to see van Schurman. The tale was first told in a contemporaneous account by Pierre Yvon in his Abregé sincere de la & de la Conduite & des vrais sentiments de feu Mr. De Labadie [which was reprinted in Supplementa illustrationes und emendationes zur Verbessurung der Kirchen-Historie, ed. by Gottfried Arnold, Frankfurt, 1703, pages 282-83]. The visit did not go well. As the two philosophers sat and chatted, Descartes noticed a copy of the Hebrew Bible on van Schurman’s desk. He asked her why someone of her erudition and talent would waste her time reading the Bible in Hebrew, its original language, when it was of such little importance. As one would expect, van Schurman was deeply offended by this remark. She replied that one could not understand Holy Writ without reading it in the original, for no translation could truly do it justice. He replied that he had once attempted to interpret the first book of the Hebrew Bible, Genesis—reflecting a comment he had written to Mersenne years earlier—but had been unable to make much headway in understanding the words of Moses (cf. AT 4: 700-01). She was greatly surprised by his attitude, and resolved at that moment never to hold a discussion with the French philosopher again. As fate would have it, they could not have met again anyway: Descartes traveled to join Queen Christina’s court in Sweden a short time thereafter, and died in Sweden the next year.

Ultimately, van Schurman was not satisfied with the life of intellectual fame in Utrecht that she had forged for herself in her early years. She certainly stood at the center of an impressive, international network of scholars and philosophers (Pal 2012). As Anne Larsen shows in her extensive biography, van Schurman’s correspondents and interlocutors included Queen Christina of Sweden, Marie du Moulin, Descartes, Mersenne, Gassendi, Constantijn Huygens, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, Dorothy Moore in England, William Penn, etc. Van Schurman corresponded with these figures, and many more, in Dutch, French, Greek, Latin and Hebrew. By the early 1640s, her fame extended throughout Europe. And yet for all this, van Schurman did not feel satisfied. Perhaps she felt that she lacked a true community. In the event, she made a radical choice late in life: having met a former French Jesuit by the name of Jean de Labadie, who had developed a reputation as a famous preacher and radical theologian, she decided to relinquish her comfortable life of fame in Utrecht and begin a trek across much of northern Europe as a member of Labadie’s growing community of believers. This decision would carry her for roughly the last decade of her life (she died in 1678). The famous story of van Schurman’s last encounter with Descartes is relayed from a nearly contemporaneous account originally written in 1670, a text concerning the life and teachings of Jean de Labadie written by one of his acolytes, Pierre Yvon. Van Schurman’s life among the Labadists contains many intriguing clues to her developing ideas about education, philosophy, theology and religion. Her choice to follow Labadie is especially interesting.

Jean de Labadie was a French religious figure of considerable importance in the mid-to-late 17th century; he gathered a significant following and caused a number of religious and political disturbances in the course of his life. As a young man from Southwest France, Labadie began his studies as a Jesuit and soon gained a reputation as a fiery orator and compelling speaker. However, by late 1638, he requested that he be allowed to leave the Jesuit order, a request that was granted the following spring.

This action was the first in a long line of such moves by Labadie: throughout his life, he joined one religious group or another, only to decide later that his co-religionists did not meet his spiritual requirements. He was also something of a rabble rouser. Over the years, he lived in, and was eventually chased out of, Paris, Port-Royal, Utrecht, Herford, and Amsterdam (Pal 2012, 238ff). It was therefore not surprising that he decided in the end to found his own religious community, and found it difficult to settle his community in a permanent home. Before he began his own sect, however, he traveled extensively in northern Europe, joining one group or another for a time, then breaking with their doctrine later. For instance, after leaving the Jesuits and traveling widely, he eventually made his way to the free Calvinist city of Geneva. He quickly made a strong impression there: within a month of his arrival in 1659, he had become a pastor in the Calvinist church and was soon a wildly popular orator, one known widely for his three-hour sermons (Saxby 1987, 11-15, 105-6). Despite his great success, he also had a knack for upsetting powerful people: it turns out that at this time, he had already promised a congregation in London that he would become their minister. Quite soon after, the Speaker of the Long Parliament in England, William Lenthall, who had famously defied King Charles years earlier, wrote to Geneva objecting to Labadie’s stay there. Eventually, this dispute was resolved, but Labadie was not destined to remain in Geneva for long. Although the leaders of the city asked him to stay, by 1666 he had decided to forge a new path once again. This time, Labadie and his growing following traveled together to Utrecht where they stayed with Anna Maria van Schurman for ten days. Labadie had met van Schurman’s brother Johann in Geneva years earlier, so he was confident that he would find a welcome refuge at her home in Utrecht (Saxby 1987, 117-18, 129, 138-9). This initial short stay would radically alter van Schurman’s life as well as Labadie’s philosophy. He dedicated his next work, Le triomphe de l’Euchariste, to van Schurman because (he said) they shared an understanding of the Christian spirit. Not long after this initial visit, van Schurman made a radical decision: she resolved to leave her comfortable life in Utrecht as a famous intellectual figure and join the growing, but itinerant, Labadist community. In 1669, van Schurman and several others, including her maid and her nephew, traveled to Amsterdam and stayed on the ground floor of Labadie’s new home there. Van Schurman’s friends considered this to be a seriously controversial and unwise decision (Pal 2012, 238-44; Saxby 1987, 177), and her time in Amsterdam was marked by the local community’s skepticism, and even outright hostility, toward Labadie and his followers. Van Schurman was perfectly well aware that her decision would be controversial, but chose it anyway (Irwin 1989, 180-1). Even in the famously freethinking and liberal city of Amsterdam—a reputation it enjoys to this day—the Labadists were considered radicals who challenged political and religious institutions too sharply and forcefully. The citizens of Amsterdam objected to Labadie’s public contention that no institution had the right to legislate against the conscience of individual believers and communities like theirs (Saxby 1987, 156). Consequently, in 1670, the Labadists decided to follow van Schurman’s lead by seeking refuge in the Abbey at Herford controlled by her old friend from the Hague, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, a powerful royal figure who van Schurman had mentored in her youth. It was another fateful choice. Princess Elisabeth had welcomed van Schurman and her community to enjoy the free land under her control within the larger Prussian Empire (in present day Germany). Roughly fifty of them arrived at the Abbey, with van Schurman and Labadie at their head (Saxby 1987, 197), in October of that year.

The Abbey at Herford was founded in 820 and included considerable lands around the town in which it was situated. The convent had survived the Reformation, and became a Protestant institution. As the Abbess, Princess Elisabeth and the two dozen members of the Abbey enjoyed significant autonomy: their lands were known as “Stifts-freiheit” or independent lands within the Duchy of Brandenburg-Prussia—this meant that the Princess was formally required to report only to the Emperor himself. These conditions must have given van Schurman and the Labadists confidence that they may have finally found a stable home for their growing but controversial, if not persecuted, community. Certainly, they all placed great faith in Princess Elisabeth’s judgment and influence, and she had ensured them that her cousin, Elector Friedrich William of Brandenburg, had given her official permission to provide refuge to Labadie and his flock. In a clever move, Princess Elisabeth described the Labadist community to her cousin as a “convent” led by the now famous van Schurman, noting that Labadie was their preacher (Pal 2012, 246-48). Alas, controversy continued to follow their young community. Although the Abbey provided van Schurman and the Labadists with a safe haven, the surrounding townsfolk did not share Princess Elisabeth’s open mindedness and liberal attitude toward religious pluralism. Like the community in Amsterdam, the people of Herford and environs were greatly displeased that a controversial group of religious refugees had settled in their town. They expressed their displeasure to the local authorities, hoping that they would send the Labadists on their way. When this failed, they took matters into their own hands: they smashed windows in van Schurman’s bedroom, pelted the Labadists with mud as they walked through town, and even tried to prevent them from drawing water at the local well (Saxby 1987, 199). It can be difficult for us to understand these events now, so it is beneficial to remember that this was a time of great religious strife throughout both Britain and Continental Europe, with numerous conflicts and wars involving religion and factionalism. In addition to the well-known conflicts between Protestants and Catholics, the Labadists, like the Quakers and others, were part of the growing number of new Protestant sects that not only rejected Catholicism, but also the authority of the more recently founded Lutheran and Calvinist churches that existed in many regions throughout northern Europe. This helps to explain the actions of the townspeople of Herford, but from another point of view, it also helps to underscore how profoundly important Princess Elisabeth’s liberal attitude toward religion was at this time. She knew, as did van Schurman, that she was taking a great risk in providing refuge for their band of religious radicals, just as Labadie and van Schurman were taking a great risk in separating themselves from all forms of established religion at that time. Moreover, by deciding to stay under the Princess’s protection in Herford, everyone involved was consciously testing the limits of local political control within the larger context of the evolving boundaries of Brandenburg-Prussia in the late 17th century.

For a time, van Schurman and her community of exiles remained safe under Princess Elisabeth’s care. In June of 1671, the Elector officially decreed that he would be continuing the policy of toleration that his cousin Elisabeth had been advocating, thereby allowing the Labadists to remain unscathed in Herford. However, this liberal policy clearly did not reflect the sentiments of the local townspeople (Saxby 1987, 207). From their point of view, the Labadists were hidden Jesuits—this was a Protestant region that would be expected to reject Catholic influence—and also, somewhat incongruously, secret Quakers (Saxby 1987, 208). The local peace was not destined to last: after much struggle and continuous claims of heresy by the local people, a strong ruling against the Labadists was finally passed. At the end of October, 1671, the Reichskammergericht, which asserted its authority over Princess Elisabeth’s lands, ruled that the Labadists were actually a radical sectarian group filled with Quakers and Anabaptists, and that they therefore must leave the lands where only Lutherans and Reformed Protestants were legally allowed to live (Saxby 1987, 210). However, Princess Elisabeth continued to believe that she possessed the ultimate authority to determine the fate of the community living on her lands, so she undertook a long journey to Berlin to appeal the proclamation of the council. After an extensive deliberation, she prevailed: in early May of 1672, the Elector proclaimed that the council had overstepped its bounds and instructed them not to undermine the Labadists any further (Saxby 1987, 216). However, by this time, the damage had been done: van Schurman and Labadie decided that they had probably overstayed their welcome in that region of Prussia, despite Princess Elisabeth’s heroic efforts on their behalf, so they resolved to find another home for their community.

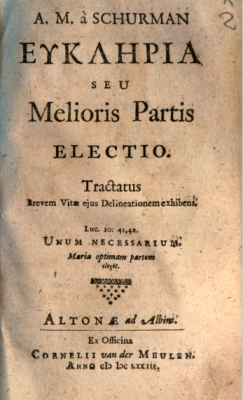

The Labadists< left Herford and eventually settled in Altona, a town which was then under the dominion of Denmark (it is adjacent to present-day Hamburg). Although they remained for just two years, from 1672-74, two important events in the life of the community took place there. First, in 1673 van Schurman published one of her most influential works, Eukleria, which has been called “the most significant of all Labadist writings,” and which was widely praised, including by Leibniz (Saxby 1987, 225). Second, after a long life of religious fervor and years of exile, Jean de Labadie died in February of 1674, leaving van Schurman as the leading intellectual figure in their still growing community. She has also been called their “spiritual leader” (Hull 1935, 10). In order to find a more permanent and safe home, the community of several hundred believers moved again, this time taking up residence in Wieuwerd, a small village in the Netherlands east of Groningen and near the coast. A community of several hundred Labadist followers remained there for a number of years (Irwin 1998, 9). It was here in May of 1678 that van Schurman died, at the age of seventy (Larsen 2016, 66-67).

It is ironic that the townspeople of Herford regarded Labadie and his followers as secret “Quakers,” because when the Quaker William Penn first visited the Labadists in October of 1671 at Elisabeth’s Abbey in Herford, he was greatly offended by what he regarded as their inhospitable attitude toward him and his cause. He wrote a long letter to Labadie and his followers that same month, criticizing them for their wayward ways and also for what he regarded as their lack of hospitality (Penn 1981, pp. 215ff). He even made some of his sentiments public, proclaiming in November 1672 in an open letter (entitled “Plain Dealeing”) that the Labadists had improperly lifted Labadie above his true station (Saxby 1987, 209-10). If nothing else, it was clear already from this first encounter that the fortunes of these two newly founded, controversial religious sects, the Labadists and the Quakers, would be intertwined in various ways. Some scholars think that Penn and the Quakers sought support from Princess Elisabeth because she had shown such clear resolve in attempting to promote toleration for van Schurman, Labadie and their followers (Hull 1935, 39-40). They sought toleration for their views as well, especially at a time in European history when the term “Quaker” was often seen as a term of abuse. For his part, the Quaker leader Penn was clearly committed not only to seeking Princess Elisabeth’s support, but also to forging an alliance with van Schurman. Although he never saw Labadie again, Penn found the time in his arduous travels around Europe promoting the Quaker message to meet once more with both van Schurman and Princess Elisabeth. He visited Elisabeth in Herford a second time, in August of 1677, and later wrote her an extensive letter attempting to convince her of his religious and theological views, warning her to avoid the temptation of following the devil [the letter is reproduced in its entirety in Bulletin of the Friends Historical Society of Philadelphia, vol. 4 (1912): 86-97]. Among other things, he tried to convince Elisabeth that some of the ministers and priests living under her protection were idolaters. Despite the sometimes overly optimistic portrayals of his biographers, one of whom characterized Elisabeth as convinced of the truth of Quaker doctrine (e.g., see Janney 1853, 126-27), Penn’s efforts were not terribly successful, as evidenced by Elisabeth’s rather terse reply to his entreaties. In her reply, which she wrote to him in late October 1677 (Bulletin 1912, 97), she did not take up any of his principal recommendations in detail, preferring to remain vague on each significant religious point, although she had adopted a friendly tone. Penn remained undeterred: soon after his visit to Elisabeth, he once again sought out her old friend, van Schurman, presumably this time as the intellectual leader of the Labadist sect. In the famous journal of his travels in Holland and Germany, which was later found among the papers of Anne Conway, Penn records some details of this second visit to van Schurman and the Labadists (Janney 1853, 125; Penn 1981, 473-74). Although he judged the first visit a failure, when he was insulted by his “unhandsomely” treatment by Labadie and his followers, Penn found the second visit, which occurred in September of 1677, far more congenial. He had hoped especially to meet personally with van Schurman during the second visit, since he had not been allowed to see her during the first. After arriving during the evening, they were brought into van Schurman’s chambers the next morning, thereby accommodating her poor health. The meeting was obviously important to van Schurman as well, since she was unable to walk by this time. Here is Penn’s description of her: she is an “Antient made above 60 years of Age, and of great note & fame for learning in Languages & philosophy; & hath obtained a considerable place among the most learned men of this age.” During their time together, Penn asked van Schurman and the other Labadists gathered in her room why they had decided to separate themselves from ordinary society and what he called “the common way,” a question that obviously went to the heart of their endeavors. Each person in attendance answered his question in turn. He records van Schurman’s answer as follows. She told Penn that she wished to add “a short Testimony” to what others had said (Penn 1981, 474). He summarizes that testimony thus: “She told us of her former life, of her pleasure in learning, & her love to the religion she was brought up in: but confessed, she knew not God or Christ all that while. And though from a child God had visited her at times; yet she never felt such a powerful stroak, as by the ministry of de Labade. She saw her learning to be Vanity; & her religion like a body of death. She resolved to despise the shame; desert her former way of living & acquaintance; & to joyn herself with this little family, that were retired out of the world: among whom she desired to be found a living sacrifice offerd up intirely to the Lord.—She spoke in a very serious and broken sense, not without some trembling. These are but short hints of what she sayd.” [Both quotations: page 474 of The Papers of William Penn, vol. 1: 1644-1679, edited by Mary Maples Dunn et al. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.] Penn’s description of van Schurman’s personal religious attitude is obviously of great significance both for understanding the development of early Quaker attitudes toward rival religious sects and also for understanding van Schurman’s own sense of the development of her life. This is also close to van Schurman’s final testament: she died just months later in 1678.

It is tempting to follow Penn’s description by dividing van Schurman’s life into two distinct periods: an early time of learning, philosophy, painting, and literature, and a later era of religious conviction and the rejection of her previous secular ways. Underlying the division, however, one might also find an intriguing thread of unity: throughout her long life, van Schurman was a woman of great conviction, and also a confident and independently minded person. She very deliberately did not allow the gender norms of her day to prevent her from achieving a deep education and a level of intellectual fame that was simply remarkable for any woman at the time. Later in life, although she rejected the secularism of her education and earlier pursuits, she nonetheless continued to pursue her own independent, not to mention risky, path in life, leaving behind her life of comfort and fame in Utrecht to join and eventually help to lead a band of religious converts whose choices would lead to their rejection and persecution in several countries. Van Schurman understood perfectly well that her early choices exposed her to criticism: she not only chose to write a work defending the education of women, a controversial topic in itself, but she also chose to embody that very life in her own person. Similarly, she did not merely defend religious toleration and freedom of conscience, she chose to embody those very principles in her personal choices at the end of her life, living in exile for a decade in accordance with her newfound beliefs. It is easy to understand why Anna Maria van Schurman, since her earliest days, has been an inspiration to so many others.

The lives of philosophers are often categorized into distinct periods, the province of the scholar. Leibniz has his early, middle, and late years, Kant his pre-critical and critical years, Wittgenstein his early and late periods, and so on. The lives of saints and religious heroes are often categorized into the worldly years, or the years marked by sin, and the holy years, or the days after a conversion or religious experience. In similar sense, Anna Maria van Schurman’s life has two distinct periods, not just on intellectual or philosophical grounds, but on religious ones as well. In her autobiography, Eukleria, published late in her life in 1673, she distinguishes these two periods and marks off her later years, the days when she was part of the Labadist community, as lacking in the worldly vanity that characterized her early years. As a young woman, as we have seen, van Schurman was immersed in a scholarly and intellectual world, and became increasingly famous for her erudition, insight and knowledge. In her final decade, she seemingly shunned this worldly, scholarly existence for a more contemplative, religiously infused life as a member of a community of outcasts and religious exiles. It is therefore quite tempting to divide her life neatly into two categories: her early years as a secular intellectual who worked at the heart of a major international network of scholars and philosophers, and her later years as a religious figure who worked at the center of a community of exiled religious thinkers and practitioners. The notion of a secular life, and of a secular community, in contrast to a religious one, employs categories that are all too familiar to the contemporary reader. Tempting as it is, however, this neat division of van Schurman’s life is anachronistic; it also misses some of the subtlety in her later work. There is no doubt that van Schurman herself divided her life into two distinct periods. But instead of distinguishing the early “secular” years from the late “religious” ones, it is more accurate to note that the division reflects a shift in her religious or theological views. Far from having a “secular” childhood and early adulthood, she tells us that she held religious and theological views in her early years that were of great importance to her; later in life, however, those views had shifted, and that shift, in turn, put her early years of study and learning into a new light for her. There is no doubt that some of the more forceful passages in Eukleria, her late autobiography, encourage her readers to interpret her life as falling into two sharply divergent periods. At times, she seems to denounce the frivolity of her youth, her youthful failure to understand the importance of the love and worship of God, her vanity in increasing her fame through study and publications, and so on. The seriousness of purpose of her late work, coupled with her intense focus on the righteous path for a Christian life, can leave one with the impression that she decided to completely reject her earlier life, its concerns and its very reason for being. But as one would expect from a philosopher like van Schurman, these passages occur within the larger context of a text that attempts to present a detailed, complex and subtle account of the change in her life’s circumstances, of her decision to leave the scholarly life behind in favor of committing herself entirely to a community of religious exiles led by Jean de Labadie. It is obvious that the details, the complexity, and the subtlety meant a great deal to van Schurman, and so they must be our guide in trying to understand her life today.

In a sign of the fame that she had acquired, the very fame that she bemoaned in certain regards later in life, van Schurman tells us at the outset of Eukleria that her goal in this text is to explain her change of life to her readers. She wants us to understand why she decided to forsake the life of a scholar for the life of a religious exile. Ironically, she approaches this task as a scholar would: she writes a detailed text in Latin with the aim of describing her life! Moreover, she approaches her task not merely as a scholar, but as a philosopher: she proclaims early on in Chapter One that she must provide reasons and arguments to defend her stark change of life—a sure sign that she had not relinquished the commitment to philosophy evident in her early writings. One of her principal arguments is that she wished to relinquish what she took to be her own vanity in her youth: she thinks in a sense that her early fame as a scholar, linguist and artist went to her head, causing her to develop a kind of self-regard and self-love that was not appropriate for a young Christian. That is, she found it difficult to maintain her humility in the face of the great fame that she had achieved. In a memorable phrase, she says that her early years were marked by a kind of “literary idolatry” (Irwin 1998, 78). She shows her philosophical stripes even more clearly when she enriches her account with what must be one of the only autobiographies to include an imagined objection to her own account of her life! She objects to herself as follows: certainly, one can understand that your early fame involved excessive praise from others, but surely your learning and study itself was appropriate. Her reply to this objection nicely expresses the subtlety of her views. She does not take this opportunity to shun learning altogether, or to proclaim that all education involves vanity. Instead, she notes that study and learning on occasion involve too much vanity. More importantly, she wishes now to place the study of the arts and sciences into a new context: the aim ought to be for the pupil to focus on those things that pertain to God purely and truly (Irwin 1998, 79). She reiterates and deepens this point in section 19 of Chapter Two: the true teacher needs not only Holy Scripture (“the book of God”), but also the book of nature, and of course, the latter book cannot be understood unless one has training in the arts and sciences. So her aim in her later years is not to reject “secular” education, as we might think of it today, but rather to underscore that the aim of education must be to bring the pupil to an understanding of God’s creation (a view that was, of course, exceedingly popular throughout the century). The study of letters is to be commended, but she again warns her reader that many who study are vain. This reading of her text is supported by her discussion of her youth in Chapter Two. She tells us that from a very early age, she felt piety. She vividly remembers a day when she was just four years old and she felt a surge of love for God as she recited the Heidelberg catechism (Irwin 1998, 79-80). In a foreshadowing of her later years, as a young person she always disliked preachers and neighbors who were not truly Christian in their actions (Irwin 1998, 87-88). She was skeptical of people who followed the letter, but not the spirit, of Jesus’s teachings. In this sense, there is an important continuity in van Schurman’s life. She ends Chapter Two with a memorable remark: she tells us that she knows for certain that the one argument that is most effective against the errors of atheists is in fact a life that has been lived in accordance with Christian virtues (Irwin 1998, 94). This focus on action late in life, rather than on purely intellectual or scholarly pursuits, has an analogue in Princess Elisabeth’s life, and shows that van Schurman was not merely a philosopher in writing, but in action.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.2 Work as an Artist

In her lifetime, Anna Maria van Schurman had several nicknames that referenced her intellectual accomplishments. One among these was the “Utrecht Minerva,” a nod to the patroness of arts and sciences from Greco-Roman antiquity. This name indeed captures the Dutch scholar’s lifelong engagement with the arts, particularly with portraiture. van Schurman lived during the early Golden Age (1588-1647), a period of rich cultural development in the Dutch Republic (Larsen 2016, 8). It is necessary to contextualize van Schurman with other painters and engravers from this period, such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Frans Hals (1582-1666), who were also known for their portraits. Yet in her autobiography, van Schurman never showed much desire to become a professional artist; instead, she considered her artistic practice as a diversion from her other humanistic pursuits (van Beek 2010, 20; van der Stighelen 1996, 57). The arts nevertheless played an integral role in the formation of her international reputation and in how she forged intellectual networks, notably among female rulers, artists, and writers such as Queen Christina of Sweden, Marie Le Jars de Gournay, and Anna Roemers Visscher (van Beek 2010, 148, 150-151, 157).

Education

The artistic education van Schurman received as a young girl included drawing, painting, sculpture, printmaking, embroidery, and paper cutting. Unlike most early-modern women artists who trained with a father, brother, or husband, van Schurman did not have any professional artists in her immediate family (Harris and Nochlin 1979, 41; van der Stighelen 1996, 58). However, her autobiography probably overemphasizes the extent of her self-teaching (Honig 2001, 33; van Beek 2010, 20). Scholars have connected van Schurman to Utrecht-based engravers, the van de Passe family. In the 1630s, she probably apprenticed with Magdalena van de Passe, whose father, Crispin van de Passe, did an early portrait engraving of van Schurman, a copy of which is now held at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (Honig 2001, 33; van Beek 2010, 20; van de Stighelen 54, 61). There is also some speculation that van Schurman received drawing lessons at Gerard Honthorst’s studio, where she would have met Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia (Birch 1909, 28; van der Stighelen 1996, 63). In 1643, van Schurman was accepted as a painter, sculptor, and engraver to the St. Luke Guild in Utrecht, but this was only an honorary title and does not confirm her as an active member of that guild (Honig 2001, 33; van der Stighelen 1996, 58, 65).

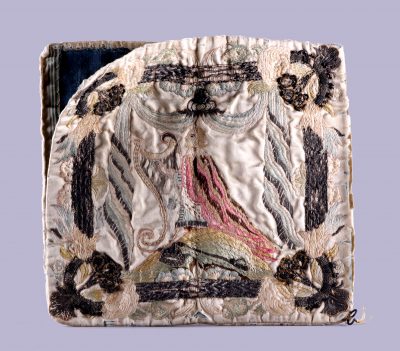

In addition, van Schurman’s parents had an impressive collection of paintings at their Utrecht home which could have inspired the young artist (van der Stighelen 1996, 60-61). Yet she appears to have preferred the handicrafts, such as embroidery, paper cutting, and drawing, which were popular among noblewomen and amateurs (van der Stighelen 1996, 57, 65). It is likely that she acquired these skills from female members of her family (van Beek 2010, 44).

Portraits and Self-Portraits

Self-portraiture was a common pursuit for early-modern women artists, who rarely had access to models and studio space. It was also considered a socially acceptable way for such women to convey their talents (Harris and Nochlin 1979, 27-28, 41; van der Stighelen 1996, 55-56). In this sense, Anna Maria van Schurman was no exception. She experimented with self-portraiture using various techniques, such as gouache, oil painting, wax- and boxwood-carving, engraving, and pencil and pastel drawing. She was in fact the first Dutch artist to use pastels (van der Stighelen 1996, 65).

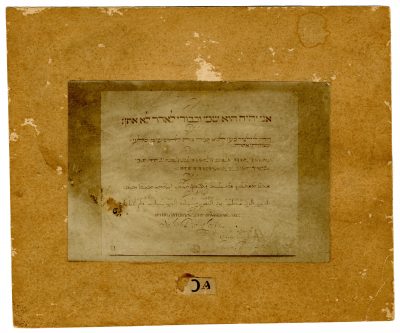

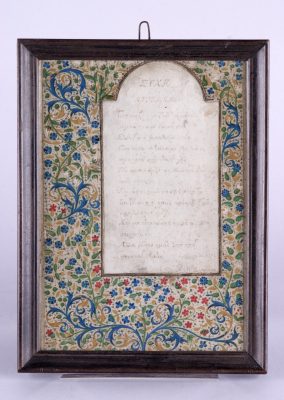

Van Schurman also painted portraits of other people, but only a few are known today. Some extant examples include miniatures of the theologians Jean de Labadie and Gisbertus Voetius, as well as van Schurman’s brother, Johan Godschalk van Schurman (De Baar 1996, 76, 97, 120). Van Schurman also demonstrated her proficiency in calligraphy and poetry by writing in others’ alba amicorum or “friendship albums,” books that contained their owner’s collection of autographs and visual memorabilia (Honig 2001, 32-33; van Beek 2010, 26).

Considering van Schurman’s experimental techniques and preference for working on a smaller scale, one may be inclined to label her an amateur artist. However, it is clear by the wide dissemination and remarkable consistency of her portraits that van Schurman considered her image as integral to her professional reputation. This speaks to her commitment to a female “Republic of Letters,” in which illustrious women across Europe exchanged their letters, ideas, and artworks (Larsen 2008).

The following extant images of van Schurman showcase her longstanding commitment to portraiture as a means of self-fashioning. While one is her earliest known engraved self-portrait, the other is a commissioned portrait done when van Schurman was at the height of her international career.

In this 1633 engraving, van Schurman presents herself in a modest but intricately wrought dress. She avoids the viewer’s gaze and hides her hands behind a quatrain that she composed. The Latin text reads, “No pride or beauty prompted me to engrave my features in the unforgiving copper; but [it was] because my un-practiced graver was not yet capable of producing good work, [and] I would not have risked a weightier task the first time” (Translation by RISD Museum). Van Schurman sent this early engraving, likely made during her apprenticeship with Magdalena van de Passe, to several people in her intellectual circle, such as Constantijn Huygens and Caspar Barlaeus. Both men responded with poems in which they interpret van Schurman’s decision to hide her hands as a reference to her virginity. But, this omission may simply have been a way for the young artist to conceal her inexperience with engraving certain features (van Beek 2010, 35-37). On the other hand, van Schurman did display her skills at calligraphy in the elegant script of her Latin poem.

Another notable depiction of van Schurman is a 1649 oil painting done by the Dutch artist Jan Lievens. Despite being completed 16 years later, this portrait shows its sitter with softer features and more conventional signs of beauty. Lievens’s use of color and light contrast in this work prioritizes the sitter’s intellect. While van Schurman’s body appears cloaked in darker fabrics, her face and book are both illuminated, thus emphasizing her knowledge and writing skills. The concentration of white brushstrokes in the middle of her forehead further highlight her brilliance. Her social status is indicated by her fur-trimmed robe and silk chemise, and by a decorative rug that covers the table. The string of pearls wrapped around van Schurman’s hair is connected to a subtle black veil, which reinforces the image of her elegance and piety. Despite the prevailing sentiment of modesty in this portrait, there are certain elements that suggest the model’s sensuality, namely the rosy hue of her lips and cheeks and her direct, lively gaze. In contrast to the more anxious look given in her engraving, van Schurman here stares out confidently and communicates an awareness concerning her representation. Indeed, Lievens’s portrait bears striking similarities to a pastel self-portrait van Schurman had completed in 1640 (above), suggesting that this painting was a close collaboration between the artist and sitter (Larson 2016, 267-268).

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.3 Chronology

| DATE | EVENT |

| Nov. 5, 1607 | Anna Maria van Schurman is born in Cologne, in the house ‘De Cronenberg’ at the ‘Krummer Buchel.’ She is born into a well-off patrician family. At three years old, she and her family flee from religious intolerance and arrive in the Netherlands. |

| 1615 | The van Schurman family moves into the house “Achter de Dom” in Utrecht, where Anna Maria resides for the next forty years. |

| 1618 | Her father, Frederik van Schurman, decides to educate Anna Maria in classics as well, alongside her brothers, after he was impressed by her immediate talent in Latin. |

| Nov. 15, 1623 | Frederik van Schurman dies soon after the family’s move to Franeker. Per her dying father’s request, Anna Maria van Schurman swears celibacy. |

| March 16, 1636 | Theologian Gisbertus Voetius invites her to present a Latin poem at the opening of the new Utrecht University. Her poem celebrates the city and its new university, and addresses the issue of women’s education. It is reprinted and gains considerable attention throughout Europe. |

| 1636 | Van Schurman becomes the first woman to study at a university in the Netherlands. Utrecht University arranges for a curtained booth to be placed in the lecture hall for her to sit in, so that other students are not distracted by her presence. She studies theology, philosophy, history, languages, and even medicine and physics. She is taken under Voetius’s wing. |

| 1638 | Charles du Chesne’s unauthorized publication of Amica Dissertatio is printed in Paris. This prompts van Schurman to expand and solidify her arguments for women’s education, which leads to the writing of Dissertatio (1641). |

| 1639 | Van Schurman’s contribution to Johan van Beverwijck’s collection on theology of medicine is published in Brittenburg, near Leiden. This is her first appearance in a serious international debate. Her contribution is titled De Vitae Termino. |

| 1641 | Van Schurman publishes Dissertatio, an argument for women’s education, through the prestigious publishing house Elzevier in Leiden. |

| 1648 | Frederick Spanheim publishes the unauthorized first edition of Opuscula, van Schurman’s collection of poems, letters, and tributes, which were written in many languages. |

| 1650 | Opuscula is reprinted. |

| 1652 | Van Schurman publishes her authorized and expanded edition of Opuscula. |

| 1653 | Van Schurman moves to Cologne for almost a year to reclaim land confiscated during the Thirty Years War. This is the first time she lives apart from the circle of Voetius in Utrecht. She experiences a different side of the Reformed Church and begins to have doubts about her theological training. |

| 1662 | Van Schurman meets Jean de Labadie through her brother, Johan Godschalk van Schurman. She is quickly attracted to his Pietist teachings. |

| 1669 | Van Schurman sells her house in Utrecht, renounces scholarly education, and joins the wandering Labadist community, lead by Labadie. She also publishes two short pamphlets, Pensées and Sérieux avertissement, that condemn the Reformed Church. |

| 1670-1672 | Van Schurman and the Labadists gain asylum at Herford Abbey at the behest of the abbess, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. Van Schurman and Princess Elisabeth have enjoyed a decades-long intellectual friendship ever since Elisabeth reached out to her in 1632. |

| 1673 | Van Schurman publishes Eukleria, her autobiographical defense of Labadism and criticism of scholasticism. |

| 1674 | Jean de Labadie passes away. Van Schurman becomes the de facto co-leader with Pierre Yvon of the Labadist community. |

| 1675 | Van Schurman and the Labadists settle in Wieuwerd, Freisland, which will be her final resting place. There she writes the continuation of Eukleria, which is posthumously published in 1685. |

| May 14th, 1678 | Van Schurman dies at age 70 from severe rheumatism, which has kept her housebound for years. |

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2. Primary Sources Guide

During her lifetime, Anna Maria van Schurman produced three major works: Dissertatio, Opuscula, and Eukleria. Each were reprinted and translated multiple times, which is an impressive statement about those works, made even more remarkable by the fact that it was by a woman scholar of the seventeenth century. She also published numerous shorter works such as poems and pamphlets, which similarly enjoyed wide circulation. Due to such wide distribution of her works, many copies today can be found in major libraries across the world. However, much of her independent shorter works were lost. This section catalogues her extant works, and it is presented in chronological order.

See a spreadsheet of which archives currently hold her works: Van Schurman ARCHIVAL RECORDS

2.1 Major Works

Amica Dissertatio inter Annam Mariam Schurmanniam et Andraeam Rivetum, De ingenii muliebris ad scientias, et meliores literas capacitate

Amica Dissertatio is an unauthorized publication of van Schurman’s correspondence with André Rivet. This text is sometimes wrongly regarded as an early edition of her renowned Dissertatio mainly for two reasons. One, it sets the groundwork for the arguments advanced in Dissertatio. Second, Pieta van Beek (2010) argues that this misconception understandably comes from this work’s rarity; she describes only a single, incomplete copy of Amica Dissertatio in Det Kongelige Bibliotek in Copenhagen, which was then assumed to be an incomplete copy of the authorized Dissertatio (2010, 109). Larsen then located three other copies of Amica Dissertatio at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris (2016, 160ff.), and one more at the Bibliothèque Municipale in Grenoble.

How was an unauthorized collection of van Schurman’s letters published? By the 1630s, many of van Schurman’s colleagues and admirers urged her to publish her letters. This included the French court physician Charles du Chesne, who also advised Princess Elisabeth to publish her own correspondence. Despite van Schurman refusing to do so, du Chesne went ahead and published an unauthorized edition of the Rivet-van Schurman correspondence anyway. Van Beek explains that du Chesne wanted to help her attain further international renown not only by publishing this demonstration of her erudition, but also by showcasing the respect she received from Rivet, a well-known scholar (2010, 110). Nonetheless, though it was compiled by du Chesne and published with the permission of Louis XIII, this unauthorized edition of their correspondence contains many printing errors, including inaccurate dating of the letters.

Van Schurman was dissatisfied with her private scholarly letters being published without her prior approval, as she made known to du Chesne in her letter to him on Feb. 18, 1640. So, two years later, she refined her arguments and put together Dissertatio, a revised and augmented work from Amica Dissertatio, and published it through the prestigious Elzevier publisher. Following this incident, she had a say in every subsequent edition of her works, as demonstrated in her letter to Rivet on July 18, 1640, where she prevented Elzevier from publishing Dissertatio before she had given her final approval.

Edition:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nobiliss. Virginis Annae Mariae a Schurman Dissertatio, de ingenii muliebris ad doctrinam, & meliores litteras aptitudine: accedunt quaedam epistolae, ejusdem argumenti.

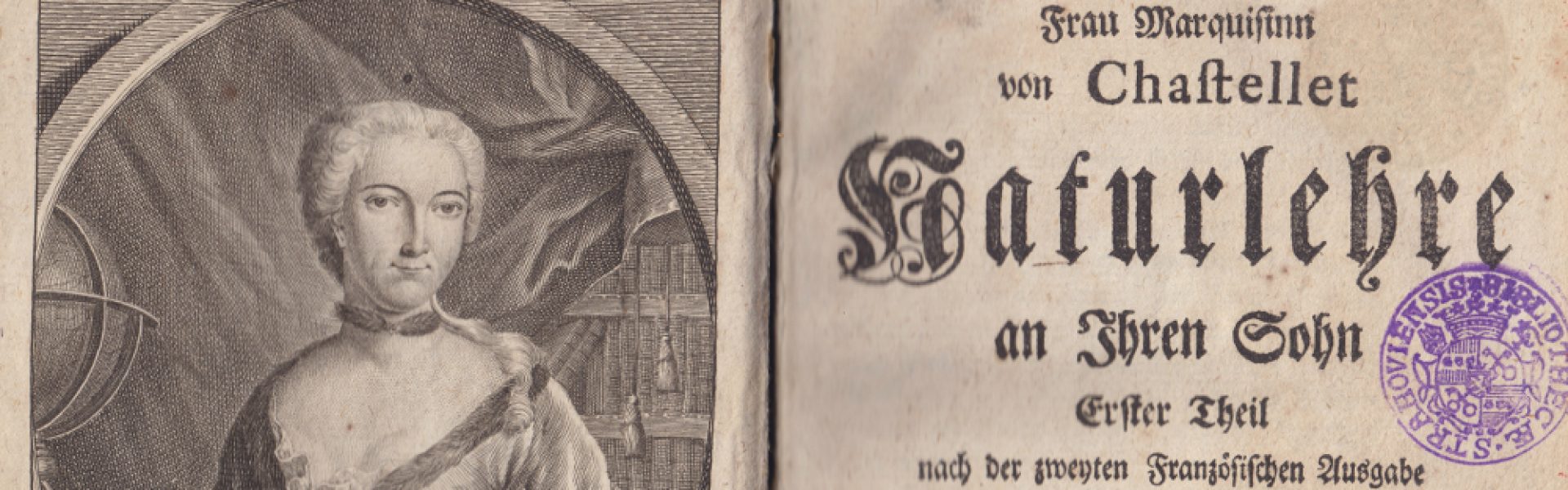

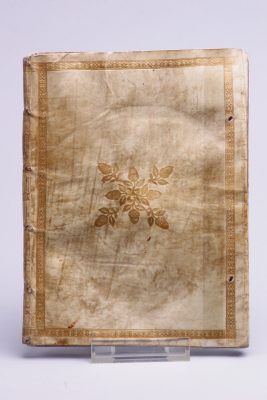

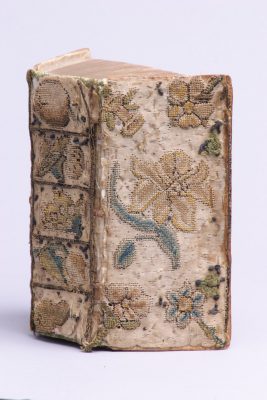

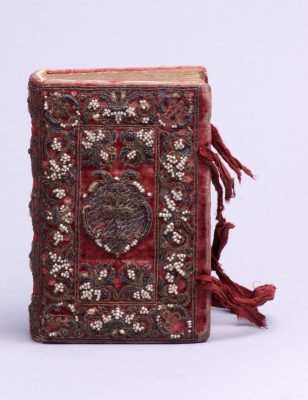

Commonly abbreviated into Dissertatio, this treatise on women’s education is her most renowned work. English editions translate the title into The Learned Maid, or Whether A Maid May Be a Scholar (trans. Barksdale, 1659), Whether the Study of Letters Is Fitting for a Christian Woman (trans. Irwin, 1998), and A Dissertation on the natural capacity of women for study and learning (trans. Clarke 2013). The work is composed of 14 theses advocating for women’s access to education. They serve three main points: 1) men and women are equally fit for learning; 2) the pursuit of knowledge allows one to elevate the “glory of God and the salvation of one’s soul” (van Schurman 1998, 26); and, 3) humans naturally want to learn, making learning an end onto itself, giving right to women to learning. She demonstrates how it is groundless for women to be barred from education, based on the premises that learning is a devotional activity and that women as members of the human species should seek to become more pious. The moderate nature of her argument may have been an important factor behind the wide acceptance of her treatise by male contemporaries (Irwin 1977, 48). Likewise, the moderate character of her argument is emphasized in her responses to the critiques by André Rivet, Andreas Colvius, Adolf Vorstius, Pierre Gassendi, Lady Moor, Simond D’ewes, and Frederick Spanheim. The work saw wide circulation across Europe, having been translated into French and English and also reprinted in Latin in 1641, 1646, and 1659. In addition to the content, another possible reason for the popularity of the work involves the prestige of the publisher, Elzevier, and the company’s trademark decorated cover. The famous Leiden-based company bound its books in highly decorated covers, which enticed many collectors to buy whatever Elzevier published. The original 1641 Leiden edition of Dissertatio was no exception. Van Beek (2010) suggests that the fanciful cover of Dissertatio played no small part to its wide ownership. She also suggests the same for van Schurman’s next publication, Opuscula (1648).

Editions:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References:

- Coffey, John. “Barksdale, Clement.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Web. Published 23 September 2004. Web. Accessed 4 March, 2019. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.duke.edu/10.1093/ref:odnb/1425.

Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica. Prosaica et Metrica

The publication of Opuscula began with Frederik Spanheim, professor of theology and rector at University of Leiden, repeatedly urging van Schurman to publish her scholarly letters, which she declined out of modesty every time. Then, in 1647, she responded more positively to him, which inspired him to publish an unauthorized edition of her letters in 1648. However, there, he had abridged some letters, removed all forms of address as well as postscripts, and eliminated the prologue and the epilogue of De Vitae Termino and of Dissertatio. When Spanheim passed away the following year, van Schurman published her own authorized and augmented edition of Opuscula in 1652, where she included those pages missing from the 1648 edition as well as additional letters, poems, and elegies.

This authorized collection of van Schurman’s works secured her international celebrity status as the “Tenth Muse” or “Star of Utrecht.” The text demonstrated the extent of her learning in Latin, Hebrew, Greek, French, and Dutch, as well as in several academic disciplines. Fortunately, many copies survive to this day, and are currently housed in major libraries across Europe and the United States. This may attest to its wide circulation. Schotel (1853) records that there have been four additional impressions of Opuscula, one from 1672 in Leiden and Herford, 1723 in Dresden, and 1749 in Leiden. However, Pieta van Beek (2010) notes that her research of two decades yielded no further evidence of those subsequent editions. Regardless, the work’s celebrity status is still remarkable, and we find mention of this work frequently in the Republic of Letters.

Van Beek argues that there are additional reasons for its popularity. Elzevier, the publisher of its first two iterations in 1648 and 1650, was one of the most prestigious publishers of the time, having many connections to book fairs across the continent and accompanying their products with an exquisitely designed cover (2010, 106). Many readers would have taken notice of Opuscula simply by its publisher. Moreover, in 1658 and again in 1678, Opuscula entered the list of banned books by the Roman Catholic Church, Index Librorum Prohibitorum, for reasons still confidential to this day. The ban, van Beek suggests, may have helped its popularity even more, as often happens with banned books.

In addition to the letters and the two scholarly works, Opuscula also includes a series of letters later referred to as “Epistola Theologica a Virginae Nobiliss Anna Schurmanna.” It records her contributions to the debate around the interpretation of 1 Corinthians 15:29, on the baptism for the dead. Lydius mentioned a separate publication of these letters, which remains untraceable today. It is his own translation of those letters that allowed it to be preserved and included in the 1641 edition of Dissertatio and all editions of Opuscula.

Exact table of contents for each editions of Opuscula can be found in the appendix of van Beek’s 1997 doctoral dissertation, cited here:

- Van Beek, Pieta. 1997. Klein Werk: De Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica Prosaica et metrica van Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678). Ph.D. diss., University of Stellenbosch, South Africa.

All but the 1749 edition of Opuscula can also be found digitized and with full access on Google Books.

Editions:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

See Current Location of Opuscula in this spreadsheet: Opuscula Locations

Eukleria seu Meliores Partis Electio (Eucleria, or Choosing the Better Part)

Two decades after van Schurman reached the heights of her scholarly fame through the popularity of Dissertatio and Opuscula, she presented a distinct view of herself in her autobiographical work entitled Eukleria. Van Schurman published this work after she had become a full-fledged follower of Jean de Labadie. In her autobiography, she reflects on her earlier life as an academic and describes the process behind her evolving attitudes towards education. The discontinuity in her stance on education prompted scholars to distinguish the early “Scholastic” van Schurman from the later “Pietist” one. But some scholars overemphasize this shift and overlook that in Eukleria, van Schurman reminds the audience of her deep commitment to piety that anchored her scholarly and artistic pursuits as a young woman.

Editions:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.2 Extant Smaller Works

Anna Maria van Schurman authored numerous commentaries, poems, and scholarly letters that exhibit complex scholarship. Mostly written in the scholarly language of Latin, or in one of the ten other languages that testify to her linguistic virtuosity, these short works demonstrate a level of learning that caught the attention of the entire continent. She used her poetry as a means of commenting on current events, participated extensively in the rapidly expanding Republic of Letters (Pal 2012). What is remarkable, however, is not just the sheer volume of her output, but the depth and the expertise with which she addressed a wide variety of academic disciplines. Her contemporaries often wrote poems celebrating her erudition, and the news of her highly unusual intellect spread across the learned world. In an extremely rare occurrence, for instance, she was featured in university textbooks at Utrecht University (van Beek 2010, 246), despite the fact that women could not formally study at any university in Europe.

Many of her shorter works were preserved because they were included in Opuscula, or survived in the Nachlass of a colleague or correspondent. The outline below details prominent and longer works that are not treatises and that have been published by themselves at least once.

De Vitae Termino

The physician Johan van Beverwijck edited a volume of letters focused on two questions: 1) should humans attempt to prolong their life, if the duration of life had been determined by God; and, 2) what is the purpose of doctors if the time of death has been predetermined? Van Beverwijck called on several famous scholars to discuss these questions through correspondence; van Schurman was the only woman to be included in the discussion. In her contribution, she argued that God must also have planned any progress in medical science, so it is permissible to prolong a life medically. Indeed, since actual death is predetermined, perhaps patients were meant to be cured so that they could die at the proper time. In that way, doctors are “partners” with God. Her contributions appear 15 times in van Beverwijck’s volume. Her letters on this topic are also later included in all editions of Opuscula except for the 1749 Leipzig edition.

Editions:

| Title | Year | City and Publisher | Language | Citation |

| De Vitae Termino | 1639 | Brittenburg (near Leiden): Johannes le Maire | Latin | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1639. “De Vitae Termino”. In Epistolica quaestio de vitae termino, fatali an mobili? Cum doctorum responsis. Pars tertia, et ultima, nunc prima edita. Seorsim accedit […] Annae Mariae a Schurman de eodem argumento epistola, totius disputationis terminus […], edited by Johan van Beverwijck. Brittenburg: Johannes le Maire. |

| De Vitae Termino | 1644 | Rotterdam: Arnold Leers | Latin | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1644. “De Vitae Termino”. In Epistolica quaestiones cum doctorum responsis, edited by Johan van Beverwijck, 1-14. Rotterdam: Arnold Leers. |

| De Vitae Termino | 1665 | Dordrecht: Rudolph a Nuyssel | Latin | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1655. “De Vitae Termino”. In Epistolica quaestiones cum doctorum responsis, edited by Johan van Beverwijck, 1-14. Dordrecht: Rudolph a Nuyssel. |

| Paelsteen van den tijd onses levens | 1639 | Dordrecht: Jasper Gorissz | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1639. Paelsteen van den tijd onses levens. Dordrecht: Jasper Gorissz. |

| Paelsteen van den tijd onses levens | 1639 | Amsterdam: Joost Broersz | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1639. Paelsteen van den tijd onses levens. Amsterdam: Joost Broersz. |

| Paelsteen van den tijd onses levens | 1647 | Amsterdam: Joost Broersz | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1647. Paelsteen van den tijd onses levens. Amsterdam: Joost Broersz. |

| Paelsteen | 1651 | Dordrecht: Jasper Gorissz | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1651. “Paelsteen”. In Schat der ongesontheyt, 51-56. Dordrecht: Jasper Gorissz. |

| Der Marckstein vom Ziel und Zeit unseres Lebens | 1678 | Unknown: unknown | German | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1678. Der Marckstein vom Ziel und Zeit unseres Lebens, translated by S.W.Z.B. s.l.: s.n. |

| Geleerde Brieven van de Edele, Deugt- en Konstryke Juffrouw, Anna Maria van Schuurman; gewisselt met de Geleerde en Beroemde Heeren Samuel Rachelius, professor in de Rechten te Kiel en Johan van Beverwijck, Med. Doct. tot Dordrecht. | 1728 | Amsterdam: Johannes van Septeren | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1728. Geleerde Brieven van de Edele, Deugt- en Konstryke Juffrouw, Anna Maria van Schuurman; gewisselt met de Geleerde en Beroemde Heeren Samuel Rachelius, professor in de Rechten te Kiel en Johan van Beverwijck, Med. Doct. tot Dordrecht. Amsterdam: Johannes van Septeren. |

| Lettres traduites du Hollandois par madame de Zoutelande | 1730 | Paris: Rebuffé | French | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1730. Lettres traduites du Hollandois par madame de Zoutelande. Paris: Rebuffé. |

Vraaghbrief, waerom de Heere Christus, daer hy ongeneselijcke Sieckten, soo met een Woordt, so met Aenraken genas, des Blindens oogen met Slick, en Speecksel gestreken heeft?

Loosely translated as “Question letter,” the Vraaghbrief is a published correspondence with Johan van Beverwijck on Jesus’s miraculous healing of the man born blind (John 9: 1-12). It is included in van Beverwijck’s “Aenhangsel van Brieven” (“attachment of letters”) appendix to the Wercken der genees-konste, bestaende in den Schat de gesontheyt, Schat der gesontheit en ongesontheit, as letter number four in their five-letter correspondence. In that same series of letters, letter number two is the above Paelsteen (Dutch translation of De Vitae Termino).

Editions:

| Title | Date | City and Publisher | Language | Citation |

| Vraeghbrief, waerom de Heere Christus, daer hy ongeneselijcke Sieckten, soo met een Woordt, so met Aenraken genas, des Blindens oogen met Slick, en Speecksel gestreken heeft? | 1642 | Amsterdam: J. Schipper | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1642. “Vraeghbrief, waerom de Heere Christus, daer hy ongeneselijcke Sieckten, soo met een Woordt, so met Aenraken genas, des Blindens oogen met Slick, en Speecksel gestreken heeft?” In Schat der ongesontheit, Aenhangsel van Brieven, edited by Johan van Beverwijck, 121-124. Amsterdam: J. Schipper. |

| Vraeghbrief, waerom de Heere Christus, daer hy ongeneselijcke Sieckten, soo met een Woordt, so met Aenraken genas, des Blindens oogen met Slick, en Speecksel gestreken heeft? | 1680 | Amsterdam: J. Schipper | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1680. “Vraeghbrief, waerom de Heere Christus, daer hy ongeneselijcke Sieckten, soo met een Woordt, so met Aenraken genas, des Blindens oogen met Slick, en Speecksel gestreken heeft?” In Schat der gesontheit en ongesontheit Part III, Aenhangsel van Brieven, edited by Johan van Beverwijck. Amsterdam: J. Schipper. |

| Lettres traduites du Hollandois par madame de Zoutelande | 1730 | Paris: Rebuffé | French | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1730. Lettres traduites du Hollandois par madame de Zoutelande. Paris: Rebuffé. |

Bedenckingen over de toekomst van Christi Koninkrijk

When van Schurman became increasingly disillusioned with the mainstream church later in her life, she expressed her religious views in her poetry. She wrote this religious didactic poem in Dutch about the future of the Church, the love between Christ and the soul, and the interpretation of Genesis 1-3. It originally circulated in manuscript form and was published later. The poem was also set to music, which was performed on September 15, 1668, in Mijdrecht at the home of the minister Van Almeloveen. This poem provides a look into her transition from the “early,” “Scholastic” van Schurman into the later “Pietist.” The poem is included in van Schurman’s Dutch translation of Jean de Labadie’s French text, Odes sacrées sur le Très-adorable et auguste Mystère du S. Sacrement de l’Autel [Sacred Odes…], Amiens, 1642. See also Van Schurman, 1992, Verbastert Christendom, edited by Pieta van Beek: 79-92.

Editions:

| Title | Date | City and Publisher | Language | Citation |

| Bedenckingen over de toekomste van Christi Koninkrijck | No date; manuscript form | No publisher | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. N.d. “Bedenckingen over de toekomste van Christi Koninkrijck”. s.a. s.l. |

| Bedenkingen van A.M. van Schuurman over de toekomste van Christi Koningryk | 1675 | Amsterdam: Jacob van Velzen | Dutch | Labadie, Jean de. 1675. “Bedenkingen van A.M. van Schuurman over de toekomste van Christi Koningryk”. In Heylige Lof-sangen ter Eeren Gods, tot Heerlijkheid van Jesus Christus, en tot Vertroostinge en vreugde van syn Kerk, translated by Anna Maria van Schurman, 326-331. Amsterdam: Jacob van Velzen. |

| Bedenckingen van A.M. van Schurman over de Toekomste van Christi Coninkrijck | 1683 | Amsterdam: Jacob van de Velde | Dutch | Labadie, Jean de. 1683. “Bedenckingen van A.M. van Schurman over de Toekomste van Christi Coninkrijck”. In Heylige gesangen.Zijn achter bygevoegt de Bedenckingen van A.M. van Schurman over de Toekomste van Christi Coninkrijk, 394-400. Amsterdam: Jacob van de Velde. |

| Heylige gesangen. Zijn achter bygevoegt de Bedenckingen van A.M. van Schurman over de Toekomste van Christi Coninkrijk | 1683 | Amsterdam: Jacob van de Velde | Dutch | Labadie, Jean de. 1683. Heylige gesangen. Zijn achter bygevoegt de Bedenckingen van A.M. van Schurman over de Toekomste van Christi Coninkrijk. Amsterdam: Jacob van de Velde. |

| Bedenckingen over de toekomste van Christi Koninkrijck | 1826 | Dordrecht: unknown | Dutch | Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1826. “Bedenckingen over de toekomste van Christi Koninkrijck”. In Mnemosyne xvi, 3-13. Dordrecht: s.n. |

Pensées d’A. M. de Schurman Sur la Reformation necessaire à present à l’Eglise de Christ.

Citation: Van Schurman, Anna Maria. 1669a. Pensées d’A. M. de Schurman Sur la Reformation necessaire à present à l’Eglise de Christ. Amsterdam: n.p.

In March 1669, she published this brief pamphlet that can be translated into “Thoughts of A. M. van Schurman on the Reformation necessary at present in the Church of Christ.” A work exhibiting her reasons for her later complete severance of ties with the mainstream church, she condemns the decline of the Church and contemporary morals for blasphemously imposing secular reason onto faith and belief (van Beek 2010, 215).

Sérieux avertissement et vive exhortation à toute sorte de Fidèles Réformés.

Citation: Samuel, Jean [pseudonym]. 1669b. Sérieux avertissement et vive exhortation à toute sorte de Fidèles Réformés. Amsterdam: Stephanus Molard.

The author of this 8-page pamphlet has typically been considered a mystery, but Larsen has recently argued (2018, 308) that the style and content closely mirror the Pensées and it should therefore be attributed to van Schurman (footnote 11). Included in the volume Jugement du Synode National des Eglises reformées des Pays-Bas tenu à Dordrecht l’an 1618 & 1619 (traduit du Latin en François), this “Serious Warning” on reformed faith is currently located at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris. Here, again, like the Pensées, she attacks the notion that faith is inferior to reason when used to justify claims, and argues that reason should not be the priority when accepting religious tenets.

Mysterium Magnum, Oder Grosses Geheimnüs das ist: Ein sehr herrliches und im heiligen Wort Gottes wohlgegründetes Bedencken Uber die Zukunft des Reichs Christi. Durch die hochgelehrte/in aller Welt beruffene und von Gott hochverleuchtete Jungfer Juffr. Anna Maria von Schurmann […].