“My mind aspires to be the theme of your sweetest songs.” – Tullia d’Aragona, Rime (1547), trans. Elizabeth A. Pallitto (2006, 79).

Tullia d’Aragona was a sixteenth-century poet, philosopher, and cortegiana honesta [honorable courtesan], a courtesan recognized and praised for her intellectual abilities. Born in Rome around the turn of the sixteenth century, she traveled to intellectual centers throughout the Italian peninsula, where she gained the favor of powerful figures who helped advance her work to publication. As d’Aragona traveled, her social status precarious—her parentage was uncertain, yet she was linked to the noble name of d’Aragona—she was a popular and talented writer, yet she faced increasing restrictions against courtesans. The complexity of her social identity mirrors the multidimensional nature of her works. While her poetry and philosophical dialogue have often been studied separately, for early modern women these seemingly disparate genres offered socially-acceptable platforms for the expression of profound ideas.

Through her Rime, a published collection of correspondence poetry; her philosophical Dialogue on the Infinity of Love (both 1547); and her epic poem Il Meschino detto Il Guerrino, d’Aragona was able to advance her own self-representation as well as the possibility of reciprocity and mutual respect in relationships between men and women. Over thirty poets and philosophers contributed to her Rime, praising her character, talent, and intellect; in her overtures and responses, she presents women as worthy equals with emotional and moral agency. In Il Meschino, she writes of the social conditions of women and includes them in her ideal audience. Of her known works it was her Dialogue that most championed women as capable of the most exalted form of love, Platonic love, previously reserved for men. Through this dialogue written in Italian, she became the first woman to enter the debate on the ethics of love and she drew upon multiple philosophical traditions and vocabularies to argue for parity between women and men. Her works were published in multiple editions throughout the early modern and modern eras, and have attracted renewed attention in the past thirty years. Through this entry on her life and works, we respond to her exhortation to her friend and literary ally Benedetto Varchi in one of her poems: “Lift up my name with your pen” (Rime, trans. Pallitto 2006, 55).

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Poet, philosopher, and courtesan Tullia d’Aragona was born in Rome between 1501 and 1505. Since the time of her birth, her parentage has been contested. She was raised by her mother Giulia Pendaglia, who was a courtesan from the Italian town of Ferrara. During the renaissance in Italy, educated courtesans such as Giulia—and later, Tullia—were admired by their patrons and enjoyed freedom of movement and wealth. The cortegiane honeste, or honest courtesans, have been characterized by Salvatore Battaglia as intellectual and sophisticated women “who [give] sexual favors in a relation of mutual respect and esteem” (Battaglia 1971, 3:863). Giulia married a Costanzo Palmieri d’Aragona of Naples who was listed as Tullia’s father on her marriage certificate (Bongi 1890, 1:152, Celani 1891, xx-xxxii).

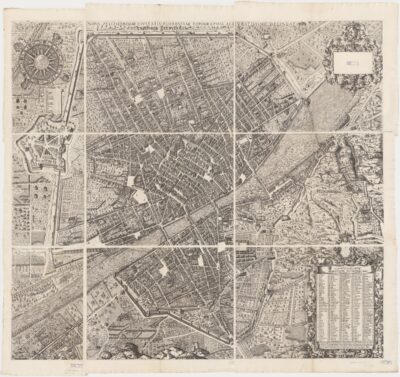

In the years 1535–1548, d’Aragona and her mother moved among Siena, Venice, Ferrara, and Florence. Rinaldina Russell has posited that these travels represent an attempt to maintain their financial and social status amid turmoil in the Italian states (Russell 1994, 23).

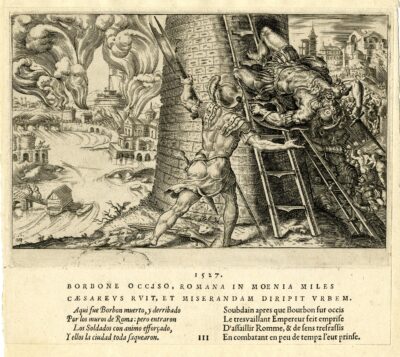

The Sack of Rome in 1527 had negative consequences for the privileged position of cortegiane honeste. After Emperor Charles V’s troops invaded the city, many artists and intellectuals who were the supporters and admirers of cortegiane honeste decamped Rome. New sumptuary legislation came into effect on a municipal basis, which meant that some cities were more tolerant of these intellectual courtesans than others. During the Renaissance, Italian societies were very concerned with the notion of belonging and knowing one’s place. Some of the most common sumptuary legislation pertaining to courtesans required them to wear a yellow veil in public as a visible marker of their occupation.

It was in Rome that d’Aragona made her entrée into courtly society through her association with the Florentine banker Filippo Strozzi (Hairston 2014). By 1535 she was hosting gatherings of literati in her home in Venice, which inspired the setting for Sperone Speroni’s dialogue on love, to which she later responded with her own dialogue (Pozzi 1978, 1:517, 527-28). Perhaps while in Venice she became aware of the printing press that would eventually become the publisher of her dialogue and poem anthology, Gabriele Giolito. Her path toward publication progressed with her sojourn to Ferrara in 1537, where she met Girolamo Muzio at the Este court. Muzio was a writer in the service of Duke Ercole II whose works were also published by Giolito. Russell has highlighted the multifaceted relationship that developed between d’Aragona and Muzio as lovers and literary collaborators. He wrote sonnets, songs, and a treatise on marriage in d’Aragona’s honor, which were published by Giolito in 1550 and 1551. He later became a literary agent of sorts for d’Aragona, facilitating the publication of her dialogue and authoring the preface. Her literary circle expanded further upon her move to Florence in the mid-1540s.

From the early 1540s, the restrictions imposed on courtesans led to legal trouble for d’Aragona. In 1544, she was denounced but then excused for not dressing in prescribed courtesan garb in Siena (documents published in Bongi 1886, 85-86). Changes in the Sienese government likely prompted her move to Florence, as her protectors were no longer in power. In Florence, d’Aragona met Benedetto Varchi, a leading figure in the literary scene (she may well have met him earlier, as he was a tutor to Filippo Strozzi’s sons). Varchi would later be depicted as the main character opposite the character Tullia in d’Aragona’s dialogue on love.

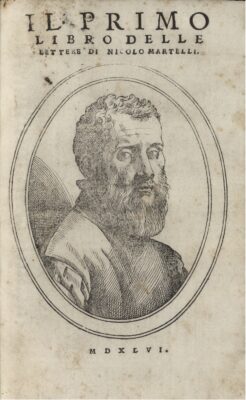

D’Aragona is referenced in Varchi’s works along with works by other literary figures she met, such as Ludovico Martelli and Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici among others. Despite her popularity in Florence, d’Aragona again encountered legal difficulty when she did not comply with the 19 October 1546 sumptuary law that required courtesans to wear a yellow covering in public.

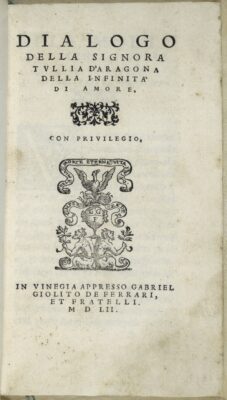

Varchi helped her petition Duchess Eleonora de’ Medici, and she was granted an exemption by Duke Cosimo I on the grounds of her “rare knowledge of poetry and philosophy” (1 May 1547, Archivio di Stato di Firenze published in Bongi 1886, 89-90; 1890, 184-85). In the months that followed, d’Aragona’s anthology of poems and dialogue were published by Giolito; the success of her dialogue led to a second edition by Giolito in 1552. Her dialogue, written in the vernacular, participated in Duke Cosimo I’s continuing campaign to promote Tuscan as the dominant dialect in Italy. From her last will and testament, we know that among her possessions were 35 books in Latin and Italian, and 13 music books along with other books and papers.

She died in March 1556 and was buried in the church of Sant’Agostino in Rome. Posthumously, her epic poem Il Meschino was published by Giovan Battista and Melchior Sessa. Her works were republished in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; it was only after the unification of Italy in 1860 that her significance in literary and philosophical history began to decline, due in part to the cultural backlash against decadence and the stigmatization of prostitution. More recently, scholars of literature, philosophy, and the Italian Renaissance have worked to restore d’Aragona’s place as a significant cultural contributor.

1.1 Portraits

Tullia d’Aragona has several portraits to her name, but none can be said with certainty to present her likeness. Just two of these portraits were completed in her lifetime. The first was done by the Lombard painter Alessandro Bonvicino, known as Moretto da Brescia (ca. 1498–1554). Sebastiano del Piombo painted the second, probably during one of d’Aragona’s periods in Rome. Little historical evidence exists to securely identify either of these portraits as the famed poet-courtesan. By the nineteenth century, however, print reproductions and an attribution by Guido Biagi had set the Moretto painting’s link to d’Aragona. The Sebastiano portrait has more recently become recognized as d’Aragona, at least since the publication of R. H. Ramsden’s book on Renaissance portraiture, Come, Take This Lute (1983).

This section assesses the two portraits through close visual analysis, incorporating contemporary images of intellectual women in the Italian peninsula and later printed portraits labelled as d’Aragona. The aim is to highlight the ongoing difficulty to reconcile d’Aragona as both a courtesan and woman of letters in sixteenth-century Italy.

In the first portrait by Moretto, a centrally positioned woman gazes at the viewer with her head cocked slightly to the side. She leans on a stone wall in regal repose, coolly eyeing her audience. This low stone wall bears a Latin inscription that leads us to identify its sitter as Salome. The inscription reads: “QUAE SACRU IOANIS / CAPUT SALTANDO OBTINUIT,” which translates to: “She who obtained the sacred head of John by Dancing” (Hairston 2010, 158). Salome was the stepdaughter of Herod, the ruler of a Roman principality in modern-day Palestine during the first century C.E. According to the New Testament Gospels of Mark and Matthew, Salome ordered the execution of John the Baptist in return for her performance before Herod and his guests at a banquet. Salome was a recurring subject in visual art during d’Aragona’s lifetime (Neginsky 2013). Titian, for example, painted multiple versions of the biblical figure, including this one done circa 1515. Moretto was in fact known for his stylistic similarities to Titian; it is even speculated that Moretto trained in Titian’s studio (Philips 1892, 156).

In the late nineteenth century, Guido Biagi identified the Moretto portrait as a faithful likeness of d’Aragona in the guise of Salome (Biagi 1886). Biagi was a Florentine journalist and historian who wrote one of the earliest monographs on d’Aragona. He published this text in 1897 under the title, Un’etera romana: Tullia d’Aragona. Multiple symbols within the Moretto painting support Biagi’s attribution. The scepter held casually in the sitter’s left hand demonstrates a graceful, but sure, sense of power. This could allude to Tullia’s noble lineage from the House of Aragona. Additionally, the sitter is richly dressed in lace, fur, and velvet. Her hair is done up into an elaborate coiffure braided with pearls.

These sartorial features establish a connection to Tullia’s high social status. With the laurel branches in the shadowy background, the image also signals d’Aragona’s intellectual pursuits in poetry and philosophy. Laurels are associated with Petrarchan poetry, a style of sonnet for which d’Aragona became well-known (Pallitto 2006, 21). In fact, through her writing, d’Aragona gained favor with Florentine nobility. Courtesans at the time were required to wear a particular yellow veil on their heads. However, because of her merits as a poet, d’Aragona appealed to the Medici court and in 1547 received an exemption from the mandate from Cosimo I. The mantle tied around the woman’s shoulders in the Moretto painting, rather than over her hair, further establishes the connection with d’Aragona’s unique circumstances as a poet-courtesan.

Biagi was not the first to connect the Moretto portrait with d’Aragona. The earliest mention of the painting comes in 1814. That year, it was acquired by Giuseppe Longhi (1766 – 1831) under the title “Herodias [the mother of Salome] with a Fur Pelt and Staff in her Hand.” Longhi owned the painting until his death in 1831. It subsequently came into the hands of collector Paolo Tosio. In 1843, the painting was transferred as part of the Tosio collection to the Commune of Brescia. The work now resides in the public museum in Brescia, the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo (Ragni 1997, 209-212).

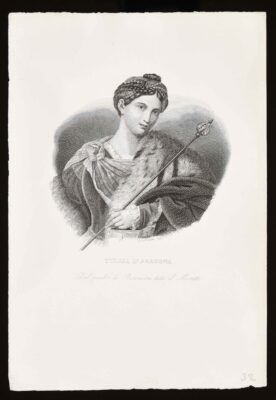

By 1897, print reproductions of Moretto’s painting had been circulating the Italian peninsula for over fifty years. These prints reinforced Biagi’s attribution. They existed as individual sheets and as illustrations in bound anthologies of poetry and philosophy. Notable examples include a print engraved by Caterina Piotti Pirola (ca. 1800 – 1850). Pirola was an engraver and draughtswoman who trained with Longhi at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, a fine arts institution in Milan. In 1823, she received the first prize in printmaking for her print after the Moretto painting (Crespi et al. 2010, 36). The caption of Pirola’s print is where we first see Moretto’s sitter identified as Tullia d’Aragona. There we also find a pair of couplets that justify the identification: “Qual fu la culla mia / Mostra lo scettro d’oro / L’ingegno mio qual sia / Mostra il crescente alloro.” This translates to: “The golden scepter points to my origins / The laurel points to my ingenuity.” With these lines, the print nods to d’Aragona’s noble lineage and her noble intellect. Interestingly, Pirola chose not to include the inscription on the stone parapet that references John the Baptist and thus the painting’s association with Salome. Biagi believed this to be a clue that the line was later added to Moretto’s painting (Pallitto 2006, 24). But restoration done in 1988 revealed the inscription as contemporary with the rest of the canvas (Ragni 1997, 209-212).

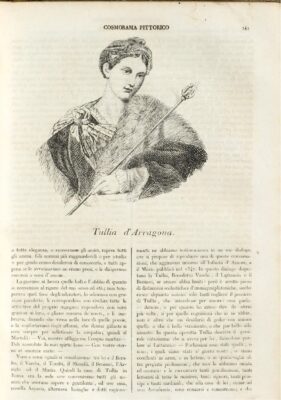

Moretto’s painting was also reproduced in other print versions. The Milanese journal Cosmorama Pittorico illustrated its 1839 article on d’Aragona with a simplified rendition of Moretto’s painting. In 1870, Salomone Eugenio Camerini published an even looser reproduction of the portrait in his collective biographies on women of letters, Donne Illustri. Biografie (Camerini 1877, 142).

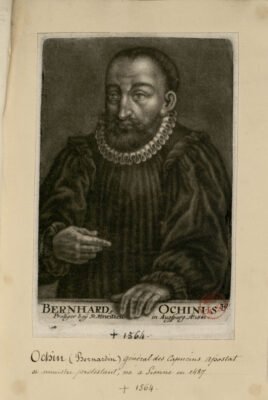

To this day, uncertainty still surrounds Biagi’s attribution. Scholars like Elizabeth Pallitto have interpreted d’Aragona’s poetry as evidence of the Salome connection. Pallitto reproduced the painting as the cover for her 2006 critical edition of d’Aragona’s poetry. There, she wrote that the label of Tullia as Salome could be a reference to the “Poem XXV” from her Rime that addresses Cardinal Bernardino Ochino. Pallitto suggests similarities between John the Baptist and Ochino, who had conservative religious views opposed to Tullia’s (Pallitto 2006, 23–29). In “Poem XXV,” Tullia calls out Ochino for the hypocrisy of his teachings, saying, “It is not holiness, but arrogance displayed/ to take away the greatest gift—free will” (Pallitto 2006, 27).

Other literary historians have contested Biagi’s association of the Moretto painting with d’Aragona. Ann Rosalind Jones, for example, has written that “Biagi’s main motive for this attribution was romantic: he thought the painting corresponded to the praises of Tullia’s fine hair and eyes by the male poets included in her Rime” (Jones 2005, 294). Julia Hairston has also expressed doubts about the identification. But she provides a productive reading of the image as both a portrait of Salome and of another, unknown, figure. Hairston writes: “It is in fact the painting’s double figuration and its paradoxical embodiment of an absence that render it relevant to Tullia d’Aragona, for she too negotiated between her dual identities as a courtesan and as a woman of letters” (Hairston 2010, 160).

The Moretto has been dated to a time when d’Aragona had just arrived in Ferrara, where she was to inspire legendary passion in the literary men at court. Years earlier, she had hosted an intellectual salon at her home in Venice. This salon later became the setting for Sperone Speroni’s Dialogue on Love, written in 1528. In his text, Speroni includes a character associated with irrational, carnal love and who he later names Tullia (Hairston 2010, 36). D’Aragona responded directly to this unflattering portrayal in her own dialogue. There “Tullia” also appears as a character. The character Tullia controls the conversation and establishes a parity between men and women in sensual and intellectual love relationships.

Although the circumstances of the portrait’s commission are unknown, it is unlikely that d’Aragona would have chosen to represent herself as Salome. As an imaginary portrait of the biblical femme fatale, Moretto’s painting alludes to the power of women’s beauty and sexuality to corrupt men. But in her writings, d’Aragona carefully crafts a self-representation that distances her work as a courtesan (Hairston 2010, 162, 341-342n14). Granted, the Moretto portrait does project the refinement that d’Aragona cultivated in her writings. Yet beyond the laurels, it says little of her learning or intellectual production as a poet.

The second supposed portrait of d’Aragona was done by Sebastiano del Piombo (ca. 1485 – 1547). It was acquired in the eighteenth century by the Earls of Radnor at Longford Castle in Salisbury, England. At the time, it was purchased as a representation of La fornarina by the celebrated artist, Raphael. Nearly a century later, however, G.F. Waagen, the Director of the Royal Gallery in Berlin, corrected this misattribution and proclaimed Sebastiano del Piombo to be the painter. Since then, the sitter has either been identified as Tullia d’Aragona or as the Countess Giulia Gonzaga. It was first linked to d’Aragona by the art historian E. H. Ramsden in his book Come, Take This Lute (Ramsden 1983, 95-106). The painting is now on extended loan from Longford Castle to the National Portrait Gallery in London. It is currently titled more vaguely as “Portrait of a Lady.” It depicts a sober woman standing in profile at three-quarter length. Her face, turned toward the viewer, bears similar features to those of Moretto’s sitter. She too is wrapped in a luxurious fur mantle, draped over her fashionable brocade gown with balloon sleeves, slashed to reveal the frilled white undergarment. Like the Moretto sitter, she wears pearls in her intricately coiffed hair.

The woman’s hands are also of interest, as hand gestures were used to communicate various messages in Renaissance portraiture. According to those conventions, the hand held to her chest could signify modesty or self-reflection. The stylized hand grasping a length of fabric could indicate her gentility and refinement. These poses are typical in portraits of courtiers. An example is another painting by Sebastiano from 1519, well-known for its identification with Christopher Columbus.

Ramsden identified the Sebastiano portrait as d’Aragona based on the sitter’s physical characteristics, like her long nose and fine eyes, and confident demeanor. Accordingly, he wrote that the portrait alludes to d’Aragona’s exceptional intellect in its “thoughtful expression” and “penetrating gaze” (Ramsden 1983, 105). The woman also wears the yellow veil that was prescribed for courtesans in d’Aragona’s lifetime. This feature was key in Ramsden’s identification. Also important was the phrase embroidered along the edge of fabric that the woman grasps in her right hand. This barely legible, shadowy hemline reads: “[Sunt] Laquei Veneris-Cave,” or “These are snares of Venus, beware.” This is a reference to Venus’ belt, thought to grant its wearer seductive powers in classical Roman mythology. Like the Moretto reference to Salome, this portrait alludes to women’s ability to elicit male desire.

How does Sebastiano’s portrait compare to those of other sixteenth-century intellectual women, particularly of poet-courtesans, created by painters of the Venetian and Roman schools? It has been suggested that Veronica Gambara is the sitter in this painting by Correggio and dated circa 1520-1524. Upon her husband’s death in 1518, Gambara became the ruler of the court of Correggio. There, she developed a thriving literary salon and produced poetry of her own. Details in the Correggio painting suggest the sitter’s widowhood, like her black overdress, the inscription on the silver chalice alluding to sorrow and memory, and the ivy, symbolic of fidelity and undying love. Positioned in a three-quarter pose, the woman turns toward the viewer and gives a slight smile. She wears a dress with dramatically bloused white sleeves and a contrasting black velvet overdress that exposes the smooth expanse of her shoulders, but no cleavage. She thus appears fashionable and attractive, yet modest. Her braided hairnet secured with a jewel signals her nobility and perhaps even alludes to her great intellect.

Other women with exceptional knowledge and creative talent were depicted with wild hair or turbans to express their genius. This portrait by Tintoretto possibly depicts Veronica Franco, another poet-courtesan alive one generation after d’Aragona. Unlike in the supposed portraits of d’Aragona, Franco’s eyes are averted so as to pose no direct challenge to her audience. Her face recedes, partially hidden in shadow, leaving her expression unreadable to the viewer. The circles under her eyes convey weariness and worldly knowledge, in contrast to the youthfulness of her pink cheeks and vibrant red hair. Her asymmetrically hung cloak, diagonal line of jewels, and low-cut bodice crisscross over the expanse of her pale chest. A hint of nipple even emerges from the bright white ruffles of her chemise. By comparison, the Moretto sitter shows much less skin and instead draws the eye with sumptuous fabrics and materials. Perhaps an attempt to champion her character, Tintoretto has depicted Franco wearing a strand of pearls, symbolic of chastity and purity. Like d’Aragona, Franco used her poems to defend her special honor above other courtesans by showcasing her intellect and network of powerful connections (Smarr 2005, 24). In her poetry, Franco counters the men who attack her as a prostitute in their verses. She openly states her worthy character and invites the reader’s admiration (King 1991, 216). The Tintoretto portrait likewise shows a woman who welcomes admiration and acknowledgement of her profession. Tintoretto, however, has omitted explicit attributes, such as quills, letters, or books, that would portray her in the intellectual persona she wrote for herself.

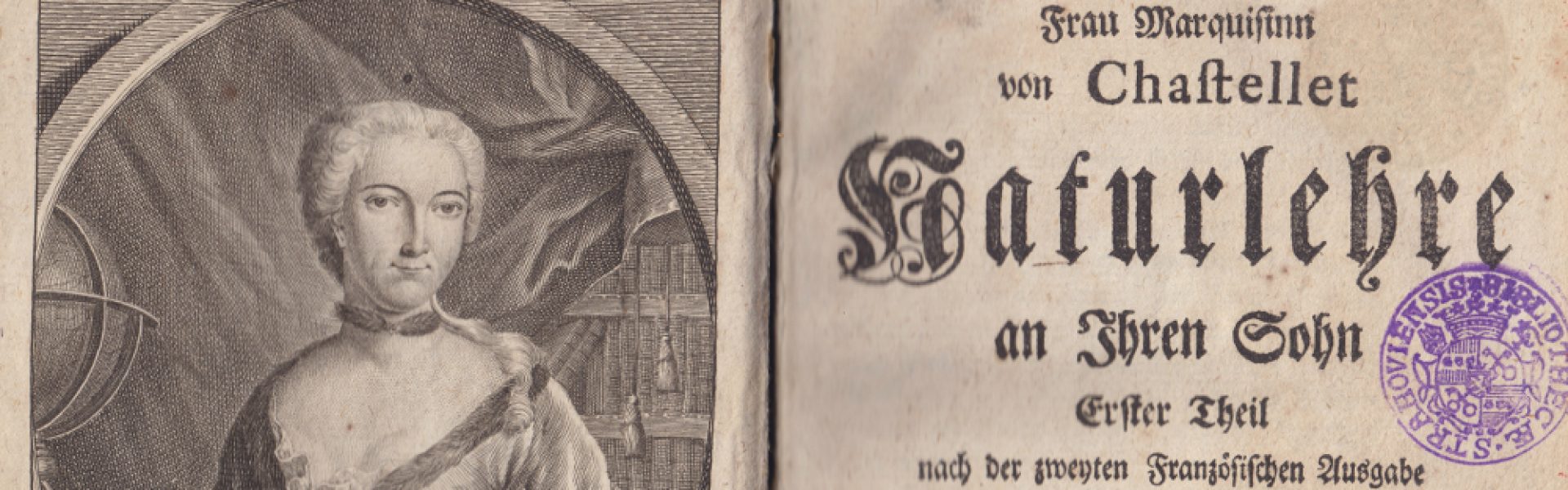

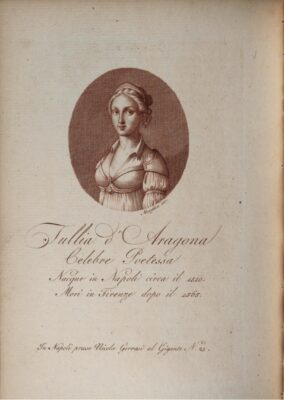

Besides the two paintings by Moretto and Sebastiano, other historical images of d’Aragona exist in print. Her portrait was included in multiple dictionaries and anthologies of poetry and philosophy that date from the late-seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Many were produced in the rich cultural and intellectual atmosphere of Milan in the early nineteenth century. As mentioned above, most of the portraits were based on Moretto’s original painting of Salome. In addition to those is a version published by Antonio Locatelli in his 1837 Iconografia italiana degli uomini e delle donne celebri.

A few other prints of d’Aragona do not reference any known paintings of her. One curious outlier is this print engraved by Morghen circa 1814. “Morghen” likely refers to Raphael Morghen, a neoclassical engraver based in Florence at the turn of the eighteenth century. This image appeared as an illustration to the second volume of the Biografia degli uomini illustri del regno di Napoli published by Nicolo Gervasi. Displaying no resemblance to other supposed representations of d’Aragona, it is perhaps based on a lost portrait. Or it may even be a purely fictional likeness. The caption also mistakes her birth and death cities, perhaps with the intent of claiming the poet-courtesan for the canon of Neapolitan intellectuals.

Another print of unknown reference is this frontispiece portrait of d’Aragona from the 1693 edition of her Rime. It portrays a woman in Baroque attire with only vaguely individualized facial features. The image more explicitly pays homage to d’Aragona in its caption, referencing her dual professions: “il ritratto della celebre Poe/tessa Tullia d’Aragona, acciò che in lui /ammiri, che non meno con le fattezze che/con l’ingegno seppe incantare i cuori di virtuosi…” In turn, this portrait probably served as the model for another frontispiece, this time for the 1864 edition of d’Aragona’s Della infinita d’amore.

A final supposed image of d’Aragona is this nude painting done by Dirk de Quade van Ravesteyn in the early seventeenth century. Van Ravesteyn was a Netherlandish painter working in Prague for the court of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II from 1589 until about 1608, the year this painting has been dated (Kaufmann 1988, 22-23, 224-225). This painting could depict one of the many common courtesans Rudolf II is believed to have kept at his court. It is currently held in Vienna at the Kunsthistorisches Museum and is labelled as a portrait of Venus. It is part of a series of mythological nudes by the artist. Another virtually identical composition is currently held in the Musée des beaux-arts in Dijon, France. In recent years, blogs and online image repositories have labelled the reclining nude in Van Ravesteyn’s painting as d’Aragona. But the dating of the work to around 1608, over fifty years after d’Aragona’s death, makes that connection tenuous. Further, there is no historical evidence that connects d’Aragona to the Netherlandish painter or the Hapsburg court. Instead, this misattribution perpetuates the same sexualized image of d’Aragona that over emphasizes her role as a courtesan. These digital-age hiccups in the historical record are akin to the nineteenth-century “modern” medium of print, which more widely spread images of d’Aragona like the Moretto painting, sometimes under weak pretenses. Rosalind Jones has likewise doubted the depiction of Gampara Stampa that appears in a 1738 edition of her Rime (Jones 2005, 300).

None of the portraits discussed above have a secure provenance that allows us to identify Tullia d’Aragona as their subject. Still, these contemporary and posthumous images are valuable to the study of d’Aragona’s legacy and reception, for they collectively convey the ongoing effort to represent her as both a woman of letters and a courtesan.

1.2 Chronology

| DATE | EVENT |

| 1501-1505/1510 | Tullia d’Aragona is born in Rome to Giulia Pendaglia. The identity of her father is disputed – while Costanzo Palmieri d’Aragona was named by Giulia, it has been posited that she did so to protect the reputation of another candidate for Tullia’s biological father, Cardinal Luigi d’Aragona. |

| 1526 | D’Aragona returns from Siena to Rome, where she is associated with Florentine banking magnate Filippo Strozzi. She becomes well known as a celebrated courtesan and accrues the patronage of notable nobles and prominent cultural figures. |

| 1530s | D’Aragona resides in Venice. Her Venetian home becomes the setting of Sperone Speroni’s Dialogo d’amore (Pozzi 1978). Her 1547 Dialogo responds in part to Speroni’s treatment of her as a character. |

| July 1535 | D’Aragona resides in Rome once again; she begins corresponding with influential poets and intellectuals. She will later include the sonnets dedicated to her in her 1547 anthology of poems. |

| June 1537 | D’Aragona is at the Este court in Ferrara, where she enjoys a period of great social success. Notably, she encounters the reformist Bernardo Ochino, to whom she later sends a sonnet on free will, as well as Girolamo Muzio (1496-1576), a writer in the service of Duke Ercole II. Muzio was also the editor of her dialogue and her long-standing publicist. |

| 8 January 1543 | D’Aragona marries Silvestro Guicciardi of Ferrara; the couple reside in Siena. |

| 1545-46 | Political unrest prompts D’Aragona’s move from Siena to Florence. This move leads to her most significant moment of literary production and patronage. |

| August 1546 | D’Aragona hosts salon-style gatherings at her home in Florence near the Mensola River. Luminaries such as the Viceroy of Spanish Naples, Pedro de Toledo, are in attendance. |

| 1547 | D’Aragona is pardoned by Cosimo I, Duke of Florence for her refusal to obey sumptuary legislation on the grounds of her “rare knowledge of poetry and philosophy.” That same year, her anthology of poetry is published by Gabriele Giolito in Venice in Summer, followed by Giolito’s publication of her Dialogo later that Autumn. |

| October 1548 | D’Aragona leaves Florence for Rome, she where she will remain for the rest of her life. |

| March-April 1556 | D’Aragona dies in Rome. She leaves behind a son, Celio (birthdate unknown), who is cared for by Pietro Chiocca. Her will testifies to her literary interests as she possessed multiple books in Latin and vernacular Italian. |

| 1560 | D’Aragona’s epic poem Il Meschino is published posthumously by Giovan Battista and Melchior Sessa. It is the first known epic poem by a woman. |

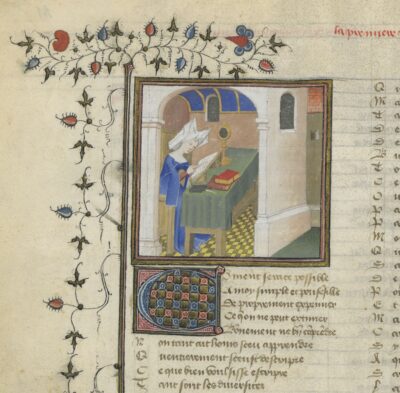

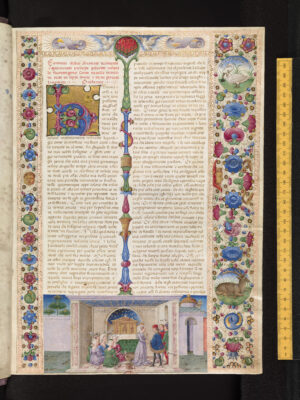

2. Primary Sources Guide

There are three published works attributed to Tullia d’Aragona: a philosophical dialogue (Dialogue on the Infinity of Love, 1547), an anthology of poems (Rime, 1547), and an epic poem (Il Meschino, 1560). While most modern scholars have found the most philosophical import in her dialogue (as a genre familiar to the discipline), there is evidence of her philosophy woven throughout her poems as well. As Lisa Curtis-Wendlandt has observed, d’Aragona makes a strong case for the poet as philosopher within her dialogue, presenting the poet as a seeker of truth who can access knowledge through other means than the traditional philosopher (Curtis-Wendlandt 2004, 86–87). The first editions of her dialogue and choral anthology were published in Venice by Giolito in 1547; their success led to reprints in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Her epic poem was published in 1560, four years after her death.

2.1 The Question of Language

Tullia d’Aragona’s choice to compose Dialogue on the Infinity of Love in Italian coincided with a historical moment in which Italian was codified and expanded. Italian was not the only language of intellectual debate in early modern Italy; many different dialects thrived on the peninsula and Latin was still dominant in universities and formal educational settings. In the 1300s, authors such as Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch had successfully raised the status of the Florentine dialect (which would become Italian) to a literary language, but the Humanists of subsequent generations also greatly revered classical Latin as they began to rediscover and study more ancient texts. By the time d’Aragona wrote, both languages were in use; as historian Paul Oskar Kristeller has argued, the literary culture of the Renaissance “found its expression simultaneously in Latin and in the respective vernacular languages” (Kristeller 1956). However, Latin and Italian were imbued with different connotations and implied different audiences.

In the sixteenth century, the Italian vernacular achieved a new status thanks to Pietro Bembo. Bembo’s 1525 Prose della volgar lingua [Discussions of Vernacular Language] responded to the ongoing debate, la questione della lingua [the language question]. This debate asked what the model for a unified, literary Italian should be and how it might compete with Latin. Bembo praises Petrarch, in particular his Canzoniere, as the model for Italian verse, and Boccaccio’s Decameron as the model for prose. Bembo’s work successfully advocated for this new, standardized fourteenth-century Italian over Latin and over more modernized versions of Italian (on the Latin tradition in Renaissance Europe see: Robert Black, Humanist and Education in Medieval and Renaissance Italy: Tradition and Innovation in Latin Schools from the Twelfth to Fifteenth Century (New York, N.Y: Cambridge University Press, 2001). In the Dialogue, Tullia aligns herself with Bembo by choosing to write in Italian and by citing his literary works in addition to those of Boccaccio and Petrarch (see Literary Sources section below).

As a woman, Tullia d’Aragona’s access to a formal education in Latin was probably limited; we know, however, that her will attests to the presence of Latin books in her library, and additional evidence suggests she knew Latin well (Favaro 2018). Even so, she decided to write in Italian, which would have made her work accessible to a wider audience, including women. It is worth noting that some of the first literature written in Italian, including Boccaccio’s Decameron, was addressed to female audiences. Moreover, Dante makes the claim in his Vita Nova that the first poet to write in the vernacular did so in order to communicate his love to a woman. D’Aragona’s Dialogue both adheres to conventions of writing about love in the vernacular, and makes a canny appeal to her dedicatee, Cosimo de’ Medici, who was invested in a campaign to make the Florentine vernacular the broadly accepted language of the diverse states of the Italian peninsula. D’Aragona significantly pushes the bounds of the vernacular, and participates in the project to elevate it to a scholarly language by showing how Italian can accommodate philosophical topics as well.

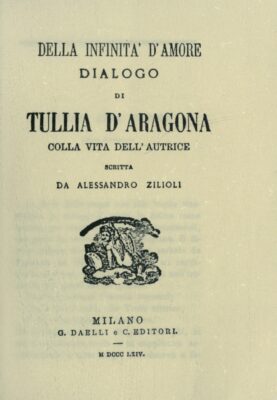

2.2 Dialogue on the Infinity of Love

D’Aragona’s Dialogue on the Infinity of Love was produced while she was in Florence, where she participated in a literary community of Florence’s most illustrious men. Among these men was Benedetto Varchi, considered one of the leading humanists of his day. The two main characters in the dialogue are Varchi and d’Aragona herself. Another speaker who appears late in the dialogue, Lattanzio Benucci, was also a close friend. Dedicated to Cosimo I, the Duke of Florence, the dialogue is written in the vernacular and contributes to the duke’s project to establish the Tuscan tongue as the dominant dialect in the Italian peninsula, then comprised of diverse city states, republics, and kingdoms. It was Cosimo’s ambition to position Florence as the cultural center of these territories, a goal furthered by the flourishing of literature, visual art, and academic societies during his rule. By writing in the vernacular, d’Aragona reaches a more diverse audience than traditional Latin treatises could do. The genre of the dialogue itself made philosophical ideas accessible to a broad audience. It presents a complex debate through a seemingly casual conversation that could bridge the gap between religious and secular morals in a courtly society. Janet Levarie Smarr identifies the dialogic form as a way for women to insert their voices into conversations from which they were traditionally excluded (Smarr 2005, 10).

As a woman, d’Aragona’s contribution to the debate on human love was unprecedented. Her dialogue draws on Platonic and Aristotelian vocabulary to articulate radical ideas about love and the discipline of philosophy. On both counts, she establishes parity between men and women, an aim that scholars have often seen as linked to her personal prerogatives as an intellectual courtesan living in an increasingly intolerant society. In d’Aragona’s time, popularizations of Platonic love were presented in dialogue form intended to be read in public settings. These debates explored the relationship among physical love, reason, religion, and morality. Early in the sixteenth century, prior to d’Aragona’s dialogue, Pietro Bembo, Mario Eqicola, Sperone Speroni, Giuseppe Betussi, Francesco Sansovino, and Leone Ebreo published Italian dialogues on love.

D’Aragona’s Dialogue on the Infinity of Love is a direct response to Speroni’s 1542 Dialogue on Love, which is set in Tullia’s Venetian home and in which Tullia appears as a character who is naturally subservient to men. His depiction of her is misogynistic, with an unflattering alignment of her character with animalistic, irrational love. Within her dialogue, d’Aragona pays homage to Ebreo’s 1535 Dialogues on Love. Ebreo’s work was innovative for the inclusion of a historic woman Sophia in the role of questioner. D’Aragona takes the role of the female character further by positioning a woman—her proxy, no less—as the main disputant. Early in her dialogue she anticipates her critics by addressing the question of whether a woman, who has an imperfect intellect in the Aristotelian view, is fit to participate in the debate. Varchi’s character is forced to concede that women surpass men in spiritual and physical beauty, and to disavow Speroni’s previous dismissal. “Women,” her character states, “reinterpret everything after their own fashion,” a point she amply illustrates through her skillful synthesis of ancient and contemporary authors to construct her own arguments (Dialogue, trans. Russell 1997, 56). She further exposes the flawed basis of the literary and philosophical tradition, as the terms of debate are largely taken from the viewpoints expressed and preserved by men (Dialogue, trans. Russell 1997, 69).

The guiding question of the debate is whether it is possible to love within limits. As the characters move through their debate, they each serve as questioner and respondent in turn, exploring a full range of human love with multiple definitions. Infinity is revealed to have multiple meanings. Varchi and d’Aragona develop their arguments jointly, a set of equals who collaborate in the pursuit of truth. This is a disputational dialogue, which allowed d’Aragona to champion her viewpoint while also preempting foreseeable critiques (Smarr 2005, 99). D’Aragona speaks in her own, authorial voice rather than through the mouth of a man; she is unchaperoned and alludes at times to her worldly experience with love. Though she never explicitly mentions her profession, d’Aragona may be leveraging her identity as a cortigiana onesta as proof that she has the right to participate in such a debate and legitimizing the conversation as a historic possibility, rather than a purely literary construct. While women were embedded in salon culture in France, sixteenth-century women in Italy participated in urban salons only if their honor was in question, as was the case for d’Aragona’ (Smarr 2005, 106). While women were understood to have experience in the realm of love, d’Aragona elevates their engagement to include Platonic love, traditionally reserved for men. Distancing herself from the base love associated with her identity of courtesan, d’Aragona argues that women’s love is also reasoned and spiritual. It is this integration of earthly and heavenly aspects of love which makes it infinite. The boundaries between honest and vulgar love are blurred – they are aspects that are present in all forms of love, for all people, to varying degrees.

Writer and friend Girolamo Muzio brought d’Aragona’s manuscript to Giolito in October 1547. The success of her dialogue prompted a second edition by Giolito in 1552, followed by a third edition in Naples published by Antonio Bulifon nearly one hundred and fifty years later in 1694. Following the unification of Italy in 1860, new cultural conservatism led to the suppression of d’Aragona’s works as “decadent” and as stigmatized by her association with prostitution (Russell 1997, 26-27). D’Aragona desired that her work would prompt new discussion and she exhorted Benedetto Varchi in a letter of 25 August 1546, “from time to time, do converse with my dialogue.”

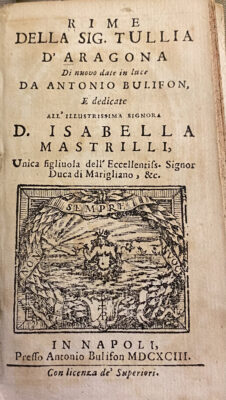

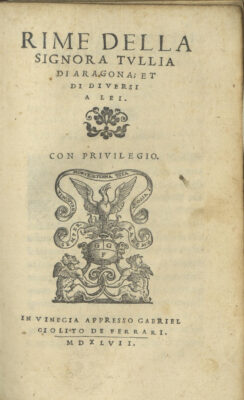

2.3 Rime

D’Aragona’s dialogic poems were published in Venice by Giolito the same year as her Dialogo (1547). Giolito published two reprints of the Rime in 1549 and 1560, which were followed by late seventeenth- and nineteenth-century editions published in Naples (1693) and Bologna (1891). The most widely-available, if partial, English translation of the original 1547 edition is Elizabeth Pallitto’s 2006 bilingual edition Sweet Fire: Tullia d’Aragona’s Poetry of Dialogue and Selected Prose. Pallitto articulates her goal of correcting inaccuracies perpetuated in the editions most available to modern scholars, many of which stem from the rearrangement and substantive changes made by Enrico Celani, the editor of the 1891 Bolognese edition. According to Pallitto, Celani’s edits conceal the political and social implications of d’Aragona’s intentional phrasing.

Though written in a different genre from the Dialogo d’Amore, the Rime can also be considered a dialogue as they represent an exchange between author and respondent. In their original Italian, these paired poems share rhyming schemes (Pallitto 2006, 12). In addition to d’Aragona, over thirty people—philosophers among them—contributed poems to the Rime. By making a public display of her personal relationships, the publication of these collected poems established a record of d’Aragona’s social and intellectual network.

As in her Dialogo and epic poem Il Meschino, d’Aragona’s volume of Rime showcases her knowledge of literary precedents. Her poems incorporate the imagery and rhetoric of Petrarch’s poetry (Pallitto 2006, 15; see also Literary Sources selection). Paralleling the dedication of her Dialogo to Florentine Duke Cosimo de’ Medici, the Rime anthology is dicated to Duchess Eleonora de Toledo. Once again, she includes herself, Benedetto Varchi, and Lattanzio Benucci as characters. These real-life allies offer public support of d’Aragona through their response-poems, such as Niccolo Martelli’s praise of her “eloquence high, immortal, and profound.” While her poems include conventional themes of beauty, love, and fame, they also advance her Dialogo’s agenda of establishing parity between the sexes in love. For example, her exchange with Alessandro Arrighi speaks of equality in passion; similarly, her poems with Antonfrancesco Grazzini (called “il Lasca”) invoke the division between soul and body. Throughout, d’Aragona emphasizes the nobility of her spirit and intellect, despite performances of gendered self-deprecation: “My mind aspires to be the theme of your sweetest songs.”

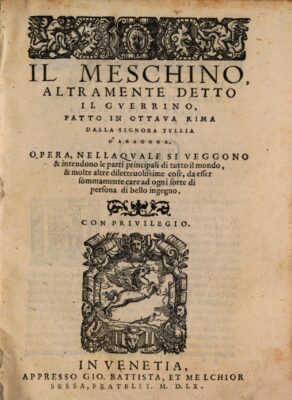

2.4 Il Meschino

Tullia d’Aragona’s final work is an epic poem, Il Meschino, altramente detto il Guerrino [The Wretched, otherwise known as Guerrino]. The text is adapted into verse from Andrea da Barberino’s fourteenth-century prose romance, Il Meschino di Durazzo. However, in a note to readers preceding the poem, d’Aragona claims her source is a Spanish romance rather than Barberino’s text. Perhaps d’Aragona hoped to emphasize the originality of her Italian verse by distancing herself from Barberino, or maybe she hoped to emphasize the originality of her Italian verse. Il Meschino tells of the journey of a man of noble birth who was captured by pirates and sold into servitude at a young age; he is called “meschino,” meaning “wretched” or “poor” precisely for this reason. After growing up as a servant in the court of the Emperor in Constantinople, Meschino ultimately proves his worth after winning a tournament (throughout which he remains anonymous), and later by winning a battle against the Turks who withdraw after an exchange of prisoners. He then embarks on a journey to discover the truth about his parentage and his name. This quest takes him across Europe, Africa, Turkey, and even includes a Dantesque visit to the afterlife. After his travels, he happily marries the Princess of Persia and saves his parents from imprisonment. While this is quite a departure from the material of d’Aragona’s Dialogue and her poems, there is some continuity in the work’s interest in love and gender; there are also new reflections on religion, gender and sexuality, and a cultural “Other.”

Unlike the Dialogo or the Rime, d’Aragona offers an explicitly moralizing voice in Il Meschino. In her opening address to readers, she censures predecessors like Boccaccio and Ariosto whom she accuses of being too lascivious in their writings. Paradoxically, her own poem is hardly free of lewd content; it, too, contains scenes of sex, violence, and questionable morality. At the same time, moralizing digressions express the author’s contempt for some of the inappropriate behaviors on display in Il Meschino. We might understand the address to readers, then, as an attempt to recast an inappropriate tale with instructions about the appropriate way one should read and interpret such scenes. This may also speak to d’Aragona’s attempt to rehabilitate her own reputation as a reputable woman later in her life. (For more on Il Meschino and its transformation of Andrea da Barberino see: McLucas, John C. “Renaissance Carolingian: Tullia d’Aragona’s Il Meschino, Altramente Detto Il Guerrino.” Olifant 25, no. 1/2 (2006): 313–20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48603110.)

2.5 Primary Sources

D’Aragona, Tullia. 1547. Dialogo della signora Tullia d’Aragona della infinità di amore. Venice: Gabriel Giolito de Ferrari.

____. 1549. Rime della S. Tvllia di Aragona, et di diversi a lei. Venice: Gabriel Giolito de Ferrari.

____. 1552. Dialogo della signora Tullia d’Aragona della infinità di amore. Venice: Gabriel Giolito de Ferrari.

____. 1553. Il Sesto Libro delle Rime. Edited by Girolamo Ruscelli. Venice: Giovan Maria Bonelli.

____. 1560. Il Meschino, altramentte detto Il Gverrino. Venice: Giovanni Battista e Melchior Sessa.

____. 1560. Rime della S. Tvllia di Aragona, et di diversi a lei. Venice: Gabriel Giolito de Ferrari.

____. 1864. Della infinità di amore: Dialogo di Tullia d’Aragona colla vita dell’autrice scritta da Alessandro Zilioli. Milan: G. Daelli.

____. 1912. “Dialogo della signora Tullia d’Aragna della infinità di amore.” In Trattati d’amore del Cinquecento, edited by Giuseppe Zonta, 185–248. Bari: Laterza. ***See especially Appendices: “Alla molto eccellente signora Tullia d’Aragona, il Muzio iustinopolitano” and “Allo illustrissimo signor Cosimo De’ Medici, duca di Firenze, signore suo osservandissimo, Tullia d’Aragona”

____. 1969. Le rime di Tulla d’Aragona: Cortigiana del secolo XVI. Edited by Enrico Celani. Bologna: Commissione per i testi di lingua.

____. 1988. Dialog über die Unendlichkeit der Liebe. Edited by Ursula Konnertz. Translated by Martin Haag. Tübingen, Germany: Diskord.

____. 1997. Dialogue on the Infinity of Love. Edited and translated by Rinaldina Russell and Bruce Merry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

____. 1997. De l’infinité d’amour. Translated by Yves Hersant. Paris: Éditions Payot & Rivages.

____. 2001. Sobre a Infinidade Do Amor. Translated by Karina Jannini. São Paulo, Brazil: Martins Fontes.

____. 2002. “A Selection of Poems by Tullia d’Aragona.” Translated by Elizabeth A. Pallitto. Forum Italicum 36, no. 1: 179–189.

____. 2006. Sweet Fire: Tullia D’Aragona’s Poetry of Dialogue and Selected Prose. Translated and edited by Elizabeth A. Pallitto. New York: George Braziller.

____. 2014. The Poems and Letters of Tullia d’Aragona and Others. Edited by Julia L. Hairston. Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies.

3. Secondary Sources Guide

D’Aragona’s critical fortune as a philosopher has been largely dependent on changing conceptions of the discipline itself. Rinaldina Russell presents d’Aragona’s work as misunderstood, not receiving its due for its mediation of the conflict between individual conduct and the ethical code imposed by religion (Russell 1997, 41). Lisa Curtis-Wendlandt argues that d’Aragona’s work and persona together invite philosophy to reflect on its disciplinary boundaries, values, and identity (Curtis-Wendlandt 2004, 93). In “Conversing on Love,” Curtis-Wendlandt makes a case for d’Aragona’s philosophical originality, a cultural contribution that has been less studied by modern scholars of philosophy than by scholars of literature, history, and gender studies. D’Aragona’s dialogue challenged fixed binary distinctions between men and women by establishing parity in their intellectual, emotional, and ethical capacities, and by drawing attention to the male-dominated voice of the philosophical tradition. Though she was recognized as a philosopher in her own time, d’Aragona has often been framed as a poet first and foremost in the secondary literature. Her disputative dialogue, poetic exchanges, and epic poem were vehicles for her philosophical ideas in forms that were considered appropriate for women; therefore, by employing a communication style that was palatable to her audience, d’Aragona could promote serious consideration of her radical ideas.

Janet Levarie Smarr analyzes d’Aragona’s dialogue within the context of the dialogues of her male contemporaries in Italy, as well as dialogues written by other early modern women. Smarr views the dialogue, along with d’Aragona’s poems, as part of a strategy of self-promotion. Through the use of an authorial voice in a character of the same name, d’Aragona shows her audience how she would like to be perceived and constructs a different role for herself. Rinaldina Russell likewise finds evidence that d’Aragona strategically obeyed literary etiquette and the cultural prerogatives of Cosimo I’s Tuscany to advance the standing of her work and persona. Her self-fashioned image as the center of an intellectual circle would be disrupted after her death, when her identity as a courtesan would be re-stigmatized. While her works regularly appeared in eighteenth-century literary encyclopedias and histories, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century there was a greater fascination with d’Aragona’s biography and association with prostitution, renewing debate about her moral status and authority. Salvatore Bongi’s archival work during this period shed new light on her struggle from the 1540s onward to preserve her image as a refined courtesan, adding new urgency to the publication of her writings to solidify her place within Florentine literary society and a courtly milieu.

3.1 Secondary Sources

Allaire, Gloria. 1995. “Tullia d’Aragona’s Il Meschino altramente detto il Guerrino as Key to a Reappraisal of Her Work.” Quaderni d’Italianistica: Official Journal of the Canadian Society for Italian Studies 16, no. 1: 33–50.

Baerstein, P. Renee and Julia L. Hairston. 2008. “Tullia d’Aragona: Two New Sonnets.” Baltimore 123, no. 1: 151–59.

Biagi, Guido. 1897. Un’ etèra romana: Tullia d’Aragona (con ritratto). Florence: R. Paggi.

Bongi, Salvatore. 1980. “Rime della Signora Tullia di Aragona; Et di diversi a lei.” In Annali di Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari. Vol. 1. By Salvatore Bongi, 150–99. Rome: Principali Librai.

Camerini, Eugenio. 1872. “Tullia d’Aragona: O la cortegiana illustre.” In I precursori del Goldoni, 197-205. Milan: E. Sonzogno.

____. 1875-76. “Tullia d’Aragona: O la cortegiana illustre.” In Nuovi profili letterari, 162–169. Vol. 4. Milan: N. Battezzati e B. Saldini.

Carolina, Beatriz. 2004. “Vandalio, el amador veleidoso de la poesia de Gutierre de Cetina.” Bulletin of Hispanic Studies (Liverpool) 81, no. 2: 155–171.

Colburn, Ethel. 1909. “Tullia d’Aragona.” In Enchanters of Men, 81–94. 2nd ed. London: Methuen.

Curtis-Wendlant, Lisa. 2004. “Conversing on Love: Text and Subtext in Tullia d’Aragona’s Dialogo della Infinità d’Amore.” Hypatia 19, no. 4: 77–98.

Dubard de Gaillarbois, Frédérique. 2017. “Il rebus di Tullia: Tullia d’Aragona e Benedetto Varchi o di una felice ‘associazione per scrivere.’” La Rivista 5: 137–52.

Favaro, Maiko. 2018. “L’auctoritas di Petrarca e la lontananza dell’amante: il caso del Dialogo d’amore (1588) di Cornelio Frangipane.” In Interdisciplinarità del Petrarchismo. Prospettive di ricerca fra Italia e Germania. Edited by Maiko Favaro and Bernhard Huss, 17–33. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore.

Giovannozzi, Delfina. 2017. “Quello scoziese a roma: Su un passaggio nel dialogo di Tullia d’Aragona.” Bruniana e Campanelliana (1125–3819) 23, no. 2: 451.

____. 2019. “Leone Ebreo in Tullia d’Aragona’s Dialogo: Between Varchi’s Legacy and Philosophical Autonomy.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 24, no. 4: 702–717.

Gleichen-Russwurm, Alexander. 1927. “Tullia d’ Aragona.” In The World’s Lure: Fair Women, their Loves, their Power, their Fates. New York: Knopf.

Hairston, Julia L. 2003. “Out of the Archive: Four Newly-Identified Figures in Tullia d’Aragona’s Rime della Signora Tullia di Aragona et di diversi a lei” (1547).” Modern Language Notes 118, no. 1: 257–63.

____. 2010. “‘Di sangue illustre & pellegrino’ The Eclipse of the Body in the Lyric of Tullia d’Aragona.” In The Body in Early Modern Italy, edited by Julia L. Hairston and Walter Stephens, 158–75. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

____. 2010. “Introduction.” In The Body in Early Modern Italy, edited by Julia L. Hairston and Walter Stephens. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

____. 2018. “L’attribuzione de Il Meschino, altramente detto il Guerrino di Tullia d’Aragona: alcuni documenti.” RR: Roma nel Rinascimento: 419–39.

____. 2020. “Tullia d’Aragona,” in Dizionario biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 97. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/tullia-d-aragona_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

Jaffe, Irma. 2002. “Tullia d’Aragona (1505/1510-1556) From Bed to Verse.” In Shining Eyes, Cruel Fortune: The Lives and Loves of Italian Renaissance Women Poets, 71–104. New York: Fordham University Press.

Jones, Ann Rosalind. 2005. “Bad Press: Modern Editors versus Early Modern Women Poets (Tullia d’Aragona, Gaspara Stampa, Veronica Franco).” In Strong Voices, Weak History: Early Women Writers & Canons in England, France, & Italy, edited by Pamela Joseph Benson and Victoria Kirkham, 287–313. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Leushuis, Reinier. 2017. “The Infinite Practice of Amorous Speaking: Tullia d’Aragona and the Venetian poligrafi.” In Speaking of Love: The Love Dialogue in Italian and French Renaissance Literature, 108–70. Leiden: Brill.

López, Maritere. 2010.“The Courtesan’s Gift: Reciprocity and Friendship in the Letters of Camilla Pisana and Tullia D’Aragona.” In Discourses and Representations of Friendship in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1700, edited by Daniel T. Lochman, Maritere López a

Marchetti Ferrante, Giulio. 1924. “Tullia d’Aragona e le cortegiane.” In Rievocazioni del rinascimento, 209–38. Bari: Laterza.

McLucas, John C. 2006. “Renaissance Carolingian: Tullia d’Aragona’s Il Meschino, altramente detto il Guerrino.” Olifant 25, no. 1–2: 313–20.

Pallitto, Elizabeth A. 2002. “Apocalypse and/or Metamorphosis: Chronographia and Topographia in Petrarch’s Sestina XXII and Tullia d’Aragona’s Sestina LV.”

Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 33: 59–76.

Phillips, Claude. 1892. “Alessandro Bonvicino, Called Il Moretto da Brescia.” The Portfolio: An Artistic Periodical 23 (January): 155–57.

Ragni, Gianfranceschi, Ida, and Elena Lucchesi. 1997. “Tullia von Aragon.” In Vittoria Colonna: Dichterin und Muse Michelangelos, edited by Sylvia Ferino Pagden, 209–12. Vienna: Skira.

Rosati, Salvatore. 1936. Tullia d’ Aragona. Milan: Treves.

Schoenberg, Thomas and Lawrence Trudeau, eds. 2006. “Tullia d’Aragona.” In Critical Discussion of the Works of Fifteenth-, Sixteenth-, Seventeenth-, and Eighteenth-Century Novelists, Poets, Playwrights, Philosophers, and Other Creative Writers. Vol. 121 of Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800. Detroit: Gale.

Segler-Meßner, Silke. 2012. “Geschlechternorm und Liebesdiskurs aus weiblicher Sicht: Tullia d’Aragona, Louise Labé und Gaspara Stampa.” In Bilder der Liebe: Liebe, Begehren und Geschlechterverhältnisse Eine Einführung, edited by Doris Guth and Elisabeth Priedl. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Smarr, Janet Levarie. 1998. “A Dialogue of Dialogues: Tullia d’Aragona and Sperone Speroni.” Modern Language Notes 113, no. 1: 204–12.

____. 2005. “Dialogue & Social Conversation: Tullia d’Aragona, Catherine des Roches.” In Joining the Conversation: Dialogues by Renaissance Women, 98–129. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

3.2 Contextual Sources

Benson, Pamela Joseph and Victoria Kirkham, eds. 2004. Strong Voices, Weak History: Early Women Writers and Canons in England, France, and Italy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Campbell, Julia D. and Maria Galli Stampino, eds. 2011. In Dialogue with the Other Voice in Sixteenth-Century Italy: Literary and Social Contexts for Women’s Writing, The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series 11.

Celenza, Christopher S. 2014. “Ideas in Context and the Idea of Renaissance Philosophy,” Journal of the History of Ideas; Philadelphia 75, no. 4: 653–66.

____. 2018. The Intellectual World of the Italian Renaissance. New York, N.Y: Cambridge University Press.

Cox, Virginia. 1992. The Renaissance Dialogue: Literary Dialogue in its Social and Political Contexts, Castiglione to Galileo. New York: Cambridge University Press.

____. 2008. Women’s Writing in Italy, 1400–1650. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

____. 2011. The Prodigious Muse: Women’s Writing in Counter-Reformation Italy Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

____. 2013. “The Female Voice in Italian Renaissance Dialogue.” MLN 128, no. 1: 53.

Crespi, Alberto, ed. 2006. Giuseppe Longhi & Raffaello Morghen: l’incisione neoclassica di traduzione 1780 –1840. Monza, Italy: Associazione dei Musei diMonza e Brianza onlus.

Edwards, Karen. 2007. “Milton’s Reformed Animals: An Early Modern Bestiary: L.” Milton Quarterly 41, no. 4: 223–56.

Feldman, Martha and Bonnie Gordon, eds. 2006. “A Case Study: The Courtesan’s Voice in Early Modern Italy,” in The Courtesan’s Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fučíková, Eliška et al., eds. 1997. Rudolf II and Prague: The Court and the City. Prague: Prague Castle Administration; London:Thames and Hudson.

Garrard, Mary D. 2020. “Artemisia and the Writers: Feminism in Early Modern Europe.” In Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe, 13-68. London: Reaktion Books.

____. 1980. “Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting.” The Art Bulletin 62, no. 1: 97–112.

Gibson, Joan. 2006. “The Logic of Chastity: Women, Sex, and the History of Philosophy in the Early Modern Period.” Hypatia 21, no. 4: 1–19.

Hankins, James, ed. 2016. The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hirst, Michael. 1981. Sebastiano del Piombo. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Iorio, Dominick A. 1991. The Aristotelians of Renaissance Italy: A Philosophical Exposition, vol. 24, Studies in the History of Philosophy. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Kaborycha, Lisa, ed. and trans. 2016. A Corresponding Renaissance: Letters Written by Italian Women, 1375–1650. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. 1988. The School of Prague: Painting at the Court of Rudolf II. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Neginsky, Roisna. 2013. Salome: The Image of a Woman Who Never Was; Salome: Nymph, Seducer, Destroyer. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Panizza, Letizia, ed. 2000. “Women and Letters.” In Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society. Oxford: European Humanities Research Centre.

Panizza, Letizia and Sharon Wood, eds. 2000. A History of Women’s Writing in Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pirillo, Diego. 2014. “Philosophy.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Italian Renaissance, ed. Michael Wyatt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ramsden, R. H. 1983. Come, Take This Lute: A Quest for Identities in Italian Renaissance Portraiture. Salisbury, England: Element Books.

Ross, Sarah Gwyneth. 2009. The Birth of Feminism: Woman as Intellect in Renaissance Italy and England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thompson, Wendy. 2007. “Antonfrancesco Doni’s ‘Medaglie’.” Print Quarterly 24, no. 3: 223–38.

3.3 Annotated Bibliography

The following sources are suggested reading for understanding Tullia d’Aragona in the contexts of her time and place, Renaissance philosophy, and literary sources.

Benson 1992. Benson, Pamela Joseph. The Invention of the Renaissance Woman: The Challenge of Female Independence in the Literature and Thought of Italy and England. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992.

Responding to Joan Kelly’s essay “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” Pamela Benson argues that early modern writers display a conflicted and dynamic understanding of womanhood and should not be treated as evidence of fixed attitudes. Building on Maclean (1980) and Jordan (1990), Benson identifies relationships in literary strategies used to navigate the notion ‘woman’ among Renaissance treatises, dialogues, and defenses to show the position of each text within a larger context. The temporal and geographic treatment of these treatises helps us understand when individual women or groups of women truly were exceptional in their socio-historical context or participating in a broader trend of activity.

Celenza, Christopher S. “What Counted as Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance? The History of Philosophy, the History of Science, and Styles of Life.” Critical Inquiry vol.39, no.2 (Winter 2013): 367–401.

In this essay, Christopher Celenza seeks to establish what, precisely, constituted philosophy in the Renaissance, and why it is rarely recognized as philosophy today. Celenza traces a shift from philosophy as a way of life to organized systems of thought. Fifteenth-century intellectuals, like the ancients, were interested in questions that linked the pursuit of wisdom to the realities of everyday life. They undertook the study of logic, rhetoric, and the other liberal arts with the goal of making life better. Celenza also shows how Marsilio Ficino and other Renaissance thinkers sought to harmonize the views of ancient philosophers. That is, they understood disparities in the works of Plato or Aristotle not as fundamental disagreements but rather as different ways to reach higher, more important truths. These characteristics distinguish Renaissance philosophy from more modern understandings of the discipline and explain why these thinkers may have been marginalized from traditional philosophical canons.

Celenza, Christopher S. The Intellectual World of the Italian Renaissance. New York, N.Y: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

This book outlines the major intellectual debates of the Italian Renaissance through an exploration of its key figures – from Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch to later Humanists such as Poggio Bracciolini, Lorenza Valla, and Marsilio Ficino. Celenza’s analysis shows how the study of language, philosophy, and literature were intimately connected for the Humanists. A key aspect of these debates is the relationship between philosophy and literature. Celenza shows how the Humanists, in particular Leonardi Bruni, believed that the kind of eloquence found in literature was necessary to the project of disseminating philosophical truths (see especially Chapter 4: Florentine Humanism, Translation, and a New (Old) Philosophy).

Cox, Virginia. “The Female Voice in Italian Renaissance Dialogue,” Modern Language Notes, 128, no.1 (2013): 53.

Cox’s essay charts the use of female figures in Renaissance dialogues from fifteenth to seventeenth century Italy. Her analysis is focused on those dialogues which are considered ‘documentary,’ that is, involving historical figures and conversations which could have, theoretically, unfolded. Her essay considers potential social and cultural factors that may have led to the inclusion of women in these dialogues such as court life and the emergence of women as powerful figures both as aristocrats and courtesans. While she admits that these dialogues did not circulate extensively in manuscript or print, she highlights the importance of female voices in intellectual debates. In a convincing analysis, Cox shows that even when women voiced and embodied traditional stereotypes in a dialogue – i.e. women are irrational – they proved themselves to be just as competent and rational as their male counterparts.

Jordan 1990. Jordan, Constance. Renaissance Feminism: Literary Texts and Political Models. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Beyond Maclean’s exploration of the ‘notion of woman,’ Constance Jordan seeks evidence of feminism in Renaissance texts from a self-identified feminist perspective. Like Maclean, Jordan recognizes that the literature is dynamic and shows a progression of thought. Jordan engages with these writings as a representation of a theory of knowledge and considers ideology in the context of cultural agents and agencies. Jordan examines Italian, French, and English texts and their circulation, organizing her texts in a way that establishes “the normative patriarchal positions on the nature and status of women and the feminist responses to them” (9).

Kelly 1977. Kelly, Joan. Kelly-Gadol, Joan. “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” In Becoming Visible: Women in European History. Edited by Renate Bridenthal and Claudia Koonz, 19–50. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

In this foundational essay, historian Joan Kelly challenges notions of historical periodization from the standpoint of women’s history by showing that women’s historical experience differs from men. She asks whether the Renaissance advanced the development of women’s social, legal, and ideological situation the way it did for men. By examining period literature for textual evidence of political and sexual norms, Kelly finds that the conditions that allow for men’s social and cultural expression can have a constraining effect on women. Kelly takes the case study of Renaissance Italy because it was “well in advance of the rest of Europe from 1350–1530” because of its consolidation of states, mercantile and manufacturing economy, and post-feudal social relations. She argues that there was no Renaissance for women, due to constraints imposed by the state, early capitalism, and changes in conceptions of sex-roles.

King 1991. King, Margaret L. Women of the Renaissance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Margaret King’s book is organized around three themes: women in relation to their families, the Church’s treatment of women in theory and practice, and powerful women of political and intellectual influence. She considers not only women’s societal roles and their treatment by others, but also their consciousness of themselves, arguing for a shift in women’s self-conception that surpassed changes in their social conditions. In her study of women’s lives between 1350 and 1650, King notes that women of the same social class living centuries apart have more in common than rich and poor women coexisting in the same place and time. By looking more closely at the specific, intersecting roles that women could occupy, we can better understand their professional opportunities and choices as cultural producers. In the first section, King shows that women were categorized in society by their reproductive status, and that women outside the reproductive cycle – prostitutes and nuns – were further marginalized.

Maclean 1980. Maclean, Ian. The Renaissance Notion of Woman: A Study in the Fortunes of Scholasticism and Medical Science in European Intellectual Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

In this book, intellectual historian Ian Maclean addresses the gap in the literature of a comprehensive modern history of woman in Renaissance Europe. His contribution is the examination of the notion of woman in Renaissance scholarly texts and its evolution. He argues that over time, the discrepancy between the notion of woman in theory and practice increases. His three areas of focus are the notion of woman, the idea of sex difference, and the relationship between sex difference and other differences. He argues that the complexity of the Renaissance notion of woman derives from inconsistencies among humanism, science, politics, economics, and social factors, which were interdependent disciplines.

Ross 2009. Ross, Sarah G. The Birth of Feminism: Woman as Intellect in Renaissance Italy and England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Ross examines the commonalities in the lives, rhetorical strategies, contemporary reception, and feminist contributions of nineteen women writers in Italy and England, 1400-1600. She rebuffs earlier feminist scholarship that positioned the early modern intellectual woman as idiosyncratic and victimized by her social condition. She illuminates sixteenth and seventeenth century patterns of intellectual collaboration among women and men, offering insight into the mechanisms of the household academy and the “intellectual family.” It must be noted, however, that she purposely excludes courtesans in her analysis. Part I focuses on the documentary record around household academies and father-daughter teams. Ross argues that the patriarch enabled the creation of “Renaissance feminism.” Part II moves from the household academy to the household salon; here Ross contend that feminists were no longer social and cultural elite, but intellectual women across the socioeconomic and disciplinary landscape by seventeenth century.

Pirillo, Diego. “Philosophy.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Italian Renaissance, edited by Michael Wyatt, 260–75. Cambridge Companions to Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139034067.016.

Diego Pirillo’s chapter offers an overview of Renaissance philosophy, examining how the rediscovery of ancient authors influenced philosophical thought of the period. In addition to returning to Aristotle in his original Greek, Renaissance philosophers engaged with the works of Plato, the Epicureans, the Stoics, and even skeptical philosophy. This new proliferation of various schools of philosophical thought challenged the authority of medieval Scholasticism and paved the way for inquiries of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Wiesner-Hanks 1993. Wiesner, Merry E. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. (Fourth Edition 2019).

Wiesner-Hanks focuses on the relationship between gender and power through three sections on the tripartite division of man as body, mind, and spirit. Women were regarded as the dominance of one part to the exclusion of the other two: married women and prostitutes by their bodies, learned women and artists by their minds, nuns and witches by their spirits. Wiesner-Hanks begins with a historiographic review of women’s history as told by social historians beginning in the 1930s. Early historians of women demonstrated that all historical change affects the lives of women in some way, though often very differently than it affects the lives of men of the same class or social group. Women as individuals were active in the public sphere as patrons, salon hosts, and writers; though they received some praise for their achievements, they also had to avoid perceptions that they were defying societal expectations, institutional rules, or the personal authority of the man within the family.

4. Philosophy Guide

Dialogue on the Infinity of Love

The topic of the debate between the characters “Tullia” and “Varchi” is introduced by Tullia’s provocation, “Is it possible to love within limits?” (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 58).

Opening Terms

The character Varchi asks whether “limit” and “end” denote the same thing. Maintaining that the two words are interchangeable, Varchi proposes that “one who has no end, also has no limit.” On this note, Varchi clarifies his position in the debate: his objective is to “prove to [Tullia] that love has no end” (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 59–60).

Essence vs. Accident

First, to clarify definitions, the character Varchi asks whether “love” and “to love” denote the same thing. The character Tullia believes that “love” and “to love” must be different because such “things … are clear and obvious in themselves.” Nevertheless, she offers a rebuttal by categorizing “love” as a noun and “to love” as a verb. On this topic, Varchi expresses his belief that nouns are “more noble” than verbs. Tullia thus points out the contradiction of Varchi’s stance that “love” and “to love” are the same thing while maintaining that there exists a difference in “degree of merit” between nouns and verbs. How can a thing differ from itself? To solve this paradox, Varchi invokes the Aristotelian concepts of essence and accident: the former pertains to the indispensable qualities of a thing, while the latter regards its expendable properties. According to Varchi, “love” and “to love” are the same in essence but may appear different when examined in other frameworks, for instance, vis-a-vis time. For example, nouns are unbounded by time, while verbs imply an event occurring in time. But since these apparent differences (or, accidents) do not conflict with the defining traits of “love” and “to love,” the essence is unchanged. Thus, from this perspective, a thing can differ from itself (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 60–62).

Varchi buttresses his point through the following example: God must love Himself, and therefore he is simultaneously the lover and the beloved. He then asks Tullia which role is nobler. Tullia chooses the latter: “Because the loved one constitutes not just the efficient and formal cause of an act, but also the final one … and the final cause is the most noble of all causes.” Varchi agrees with her analysis and then extends this premise to conclude that God, when seen as the recipient of love, is thus more noble than Himself than when viewed as the agent of love. Since the essence of God is consistent between the two situations, the apparent differences between God the lover and God the beloved are accidental qualities. Thus, God can unparadoxically differ from himself (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 63).

Platonist Division of Realms

The character Tullia, however, rejects an example using divine elements, i.e., God, insisting that humans cannot comprehend the heavenly world. This concept of a gulf between the mortal and immortal realms is rooted in Platonist and Neoplatonist philosophy: the spiritual realm of perfection cannot be fully understood in this earthly existence (Ursic and Louth 1998, 85). Tullia may be alluding to Leone Ebreo’s Dialoghi d’Amore, which argues for the inability of the human intellect to apprehend the perfection of God (Ebreo, Dialoghi 34, Russell 1997, 64n13).

Accepting Tullia’s dichotomous framework, Varchi focuses on the dialectic between physical and spiritual worlds—more specifically, between body and soul. He asks which is more “perfect:” form without matter or form united with matter, the soul without the body “or the soul and the body together?” Tullia believes that the combination of the two elements must be the worthiest, since even if the body contributes no value, its addition does not reduce the value of the soul. However, Varchi maintains that even if the soul remains unchanged by the addition of the body, the soul itself is nevertheless worthier without the corporeal component (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 65). Such scorn for the bodily element exemplifies the Platonist contempt for the imperfection of the physical and idealization of the “perfect” metaphysical (Slawson 2018). In contrast, Tullia refuses to value the physical realm as an undesirable component, an idea which figures prominently in her critique of Platonic love.

Tullia’s Definition of Love

The character Varchi asks Tullia for her definitions of “love” and “to love.” Tullia states that love is “a desire to enjoy with union what is truly beautiful or seems beautiful to the lover,” and to love is “to desire to enjoy, and to be united with, either what is truly beautiful or what seems beautiful to the lover.” These definitions draw directly from Leone Ebreo’s Dialoghi, in which Ebreo describes the connection between love and union with what is good, as well as union’s linking with human pleasure (Ebreo, Dialoghi 45, Russell 1997, 69n22). Though Varchi thinks that Tullia now agrees with his equation of the two terms, she does not believe a cause (love) can be equated to an effect (to love). Varchi responds by stating that based on her definitions, “love” and “to love” constitute an identical effect; thus, they must have an identical cause (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 69–70).

The Infinity of Love

Varchi then summarizes what he and Tullia have established: 1) “limit” and “end” are the same—whatever lacks a “limit” also lacks an “end;” whatever has no “end” can thus have no “limit;” 2) “love” and “to love” are the same in essence, despite being seemingly different when viewed with respect to time (accidental properties); and, 3) “love” causes one “to love,” so “loving” becomes the effect of “love,” which means that the cause and effect, though seemingly disparate, are essentially the same. With this discussion, Varchi believes that the initial question of “whether it is impossible to love with a limit” is thereby resolved: one cannot love with an end or limit (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 71).

Falling Out of Love

Tullia then relies on experience to object, noting that countless men have fallen out of love. This appeal to experience is reminiscent of Ebreo’s Dialoghi d’Amore, in which the character Sofia holds empirical information above Ebreo’s abstract reasoning (Ebreo, Dialoghi 50, Russell 1997, 71n25). Here, Tullia exclaims, “I want you to bow to experience, which I trust by itself far more than … the whole class of philosophers.” Varchi agrees that many people fall out of love, but argues that this fact does not imply that love has an “end.” He raises the example of the impossibility of living without eating, a fact which is not at odds with the fact that the dead do not eat. In other words, while one loves, one does not love within limits; but when one stops loving, “the issue simply does not arise.” Tullia then raises the case that some people love in order to achieve a selfish end, after which they fall out of love. Varchi does not believe such cases exist. But after Tullia insists by asserting her superior credentials in the lived experience of love, Varchi condemns those who love this way because “they give the most beautiful and precious label to what is just a vile and sordid act” (d’Aragona, trans. Russell and Merry 1997, 71–75). Here, he equates love that is short-lived and self-interested to bodily lust. This contemptuous view of loving due to physical yearnings has precedents in Plato’s Symposium, Marsilio Ficino’s Commentary on Plato’s ‘Symposium,’ and Pietro Bembo‘s Gli Asolani (Russell 1997, 75n29).

The Infinity of God