Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

“If I am condemned, I shall be annihilated to nothing: but my ambition is such, as I would either be a world, or nothing.”

“If I am condemned, I shall be annihilated to nothing: but my ambition is such, as I would either be a world, or nothing.”

– Poems (1653), dedication to “To Natural Philosophers”

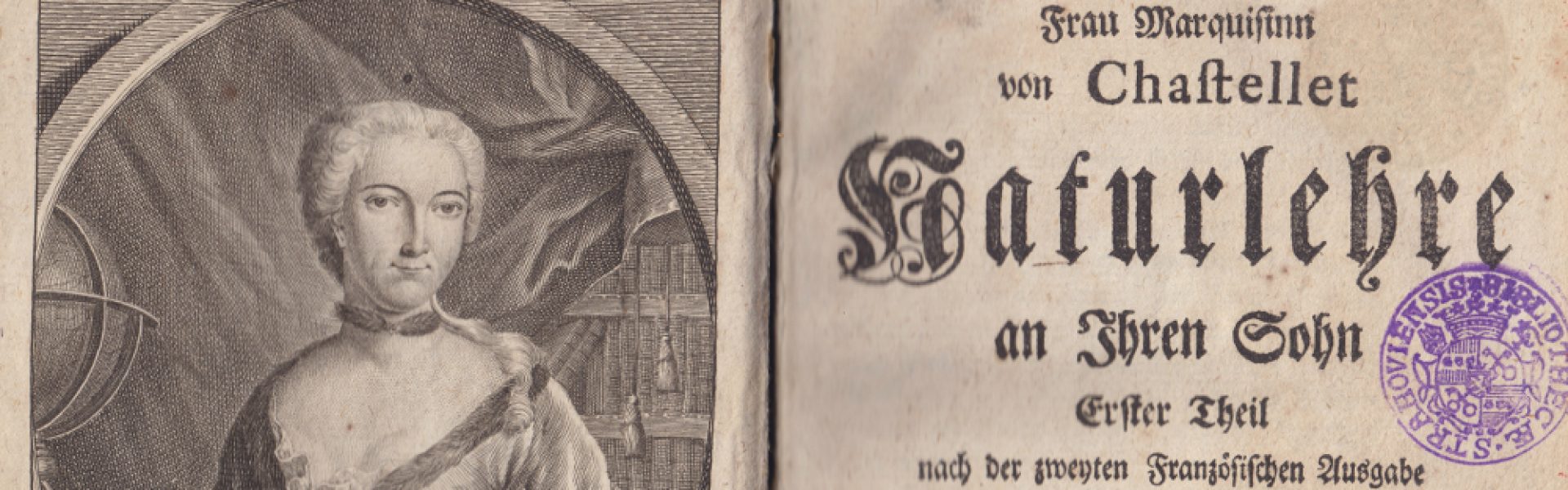

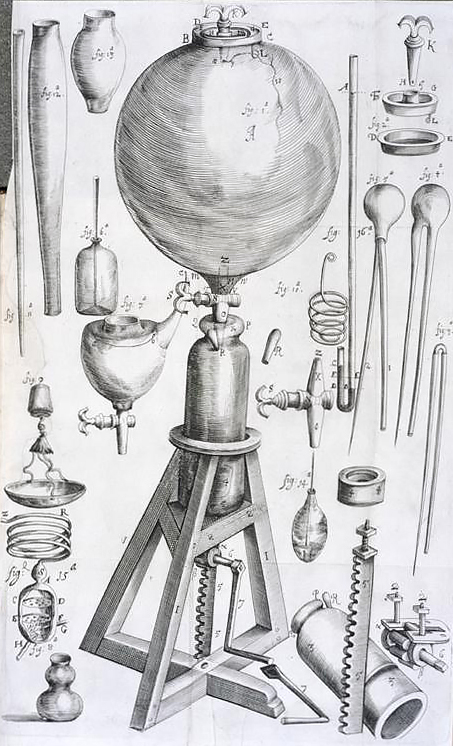

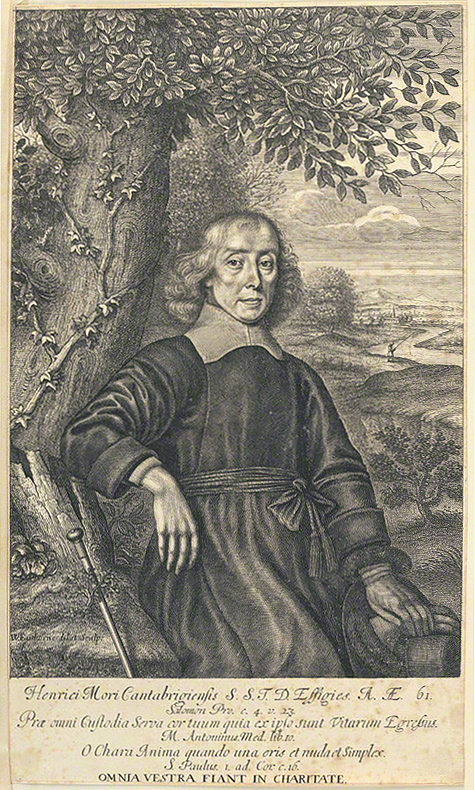

Cavendish is famous today for her plays, letters, orations, poetry and fiction, and was a very popular writer in her time. She was prolific, publishing more than a dozen original works during her life, under her own name, with her portrait proudly engraved on the frontispieces of her works. This was done at a time when most women did not publish works, let alone under their name. Cavendish was also a natural philosopher in her own right, determined to learn about the latest scientific developments and to engage in philosophical debate despite her lack of any formal education. Thanks to her high social status, and her husband’s active and supportive interest in philosophy, she was able to personally know the best minds of her time, including René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, Henry More, Walter Charleton, and Joseph Glanvill. She was also the first woman to be formally invited to visit the Royal Society and to observe the famous air pump experiments of Robert Boyle. At a time when many women writers were concerned predominantly with issues of religion, or the education of women, Cavendish trail-blazed her way by developing a unique position in natural philosophy which critiqued the dominant materialist, mechanist and dualist theories of substance and causation. Extravagant and eccentric, “mad Madge” stands alone as one of the few early modern women – the list also includes Du Châtelet – who was bold enough to stake out her philosophical position in a non-anonymous way, even at the risk of public ridicule.

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

In 1623, Margaret Cavendish (neé Lucas) was born into a wealthy aristocratic family, the youngest of the eight children of Sir Thomas Lucas and Elizabeth Leighton Lucas. Her father died when she was very young; her mother raised her. She received no formal education in science or philosophy, nor in any of the academic languages, such as Greek or Latin. Her education was typical for young ladies of her time, consisting of learning to read and write, to dance, and to sing. Unlike some aristocratic women, such as Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, she did not have private tutoring in natural philosophy, and unlike Masham or Conway, she also did not have a philosophical mentor. She was, however, precocious from an early age and having access to private scholarly libraries, she made up for her lack of education by reading. Despite her stay in France, however, she seems never to have learned French. She also benefitted from learned discussions with her brother John, who was a scholar of philosophy and natural science, and who was fluent in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek. John later became one of the founding fathers of the Royal Society. Cavendish’s lack of formal education is important, as she very often publicly decried this handicap in her works. Interestingly, given her future notoriety as eccentric, extravagant and “mad,” she is described as being very shy in her youth.As the Civil War erupted in England in 1642, Cavendish’s home at St. John’s Abbey was attacked by rebels and her family’s tomb was desecrated. Given that her father’s early death left her without a dowry, the ambitious Cavendish successfully applied in 1643 to become the maid of Queen Henrietta Maria, the Catholic wife of the soon to be executed King Charles I, and the mother of the future kings Charles II and James II.

In 1644, following more political disturbances in England, Cavendish followed the Queen from Oxford to exile in Paris. There she met her future husband William Cavendish (1593–1676), who later became the Duke of Newcastle. Cavendish’s marriage match proved to be intellectually, as well as socially, important for her. Her well-established and influential husband, thirty years her senior, was an amateur scholar very much interested in philosophy. Thomas Hobbes tutored both him and his brother Charles. William was not only able to introduce her to the most famous philosophers of the day, but also to help her publish her future works. Although Cavendish became very popular as a writer in her own right, and was prolific, it was highly unusual at the time for a woman to publish on topics in natural philosophy, and even more unusual for her to publish under her own name. Many of Cavendish’s works include a dedicatory epistle to her husband or a preface by him, which in some eyes lent the works an air of respectability. Although she did not have a dedicated philosophical mentor as Conway and Masham did, Cavendish did have the benefit of an influential husband who looked favorably upon her intellectual endeavours.

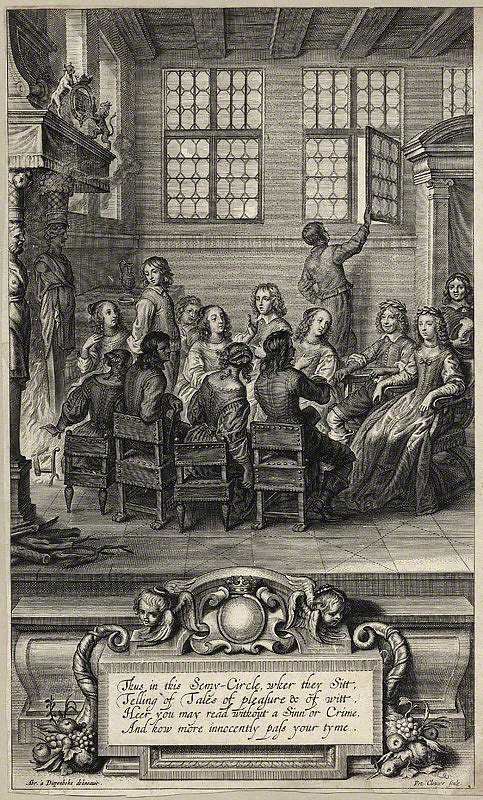

It is during their three-year sojourn in Paris from 1645 to 1648 that William introduced Cavendish to an intellectual circle of both French scholars and English scholars in exile, which soon became known as the “Newcastle” or the “Cavendish” circle. The circle included English philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes, Kenelm Digby and Walter Charleton, and French philosophers such as René Descartes, Pierre Gassendi and Marin Mersenne. The circle was also very well connected outside of Paris: William’s brother Charles Cavendish, for example, was personally acquainted with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, who in turn corresponded with Descartes, and also commented on Digby’s views. Other notable women of the time, such as Queen Christina of Sweden, whom Descartes would later tutor, and Anna Maria van Schurman, were in communication with Gassendi and Mersenne. The new mechanical philosophy discussed by these philosophers left a deep impression upon Cavendish, inspiring her to pursue natural philosophy. In 1657, she corresponded with Constantijn Huygens on the topic of Prince Rupert’s Drops, glass objects that were characterized by a curious combination of strength and fragility. By the time she returned with her husband to Restoration England in 1660, she had already penned five works, including Poems and Fancies (1653), Philosophical Fancies (1653), and Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1655), in which she begins to lay the groundwork for her alternative to the new mechanical philosophy.

After her return to England, Cavendish busied herself with reading the latest works in natural philosophy. She read Charleton, Descartes, Digby, Hobbes, and J.B. Van Helmont, considering topics as wide as dioptrics, hydrostatics and magnetic theory. She also pursued readings in ancient philosophy. By 1668, she had already published – publicly and with her name and portrait proudly displayed on the frontispieces – thirteen works ranging from treatises, fiction, plays and a biography of her husband (which proved very popular and was subsequently reprinted many times). In her works she experimented with varieties of styles and genres to express her views on natural philosophy. Instead of engaging other philosophers in academic debate, Cavendish sent her works as presents to well known scholars at universities such as Oxford and Cambridge. Dressing lavishly and acting with an affected manner, she acquired a reputation for being an eccentric and extravagant, and altogether too bold for someone of her sex. She was a society phenomenon, and her visits to London always occasioned much excitement.

During the 1660s, Cavendish was also interested in the world of experimental philosophers such as Robert Boyle, the curator of experiments at the Royal Society, Robert Hooke, and Henry Power. On May 30th, 1667, she gained even more notoriety for being the first woman to attend a meeting of the Society. Cavendish not only attended, but she was also formally invited, partly due to the intervention of her friend Walter Charleton, who lobbied on her behalf. At the Society, she observed Robert Boyle’s experiments with the air pump, and his experiments with mixing colours, with the assistance of Robert Hooke. She was delighted. The visit caused such a sensation that Samuel Pepys thought it worthy of an entry in his Diary, having spent some time pushing through the crowds to get a glimpse of her sumptuous carriage.

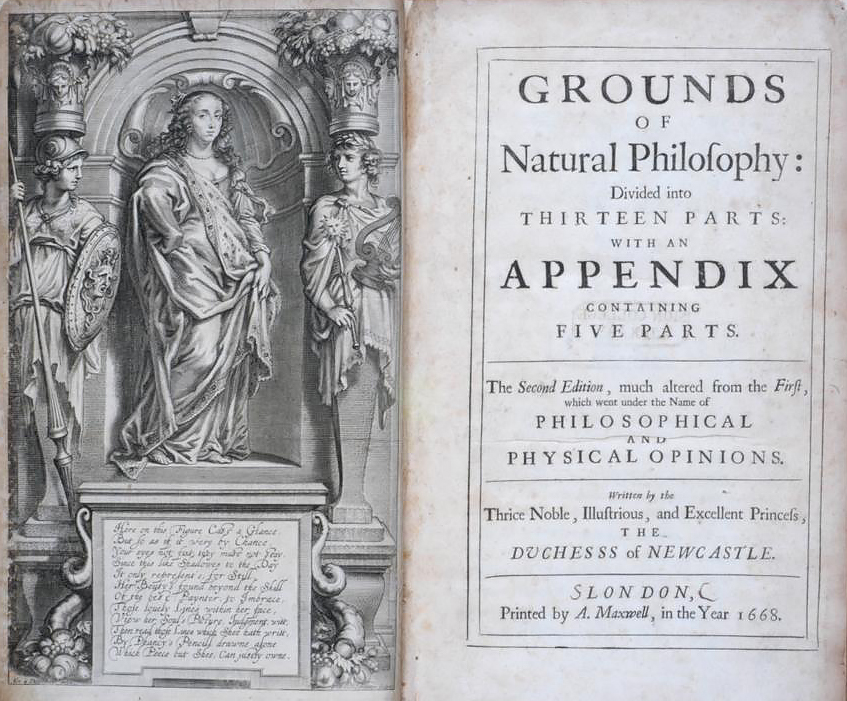

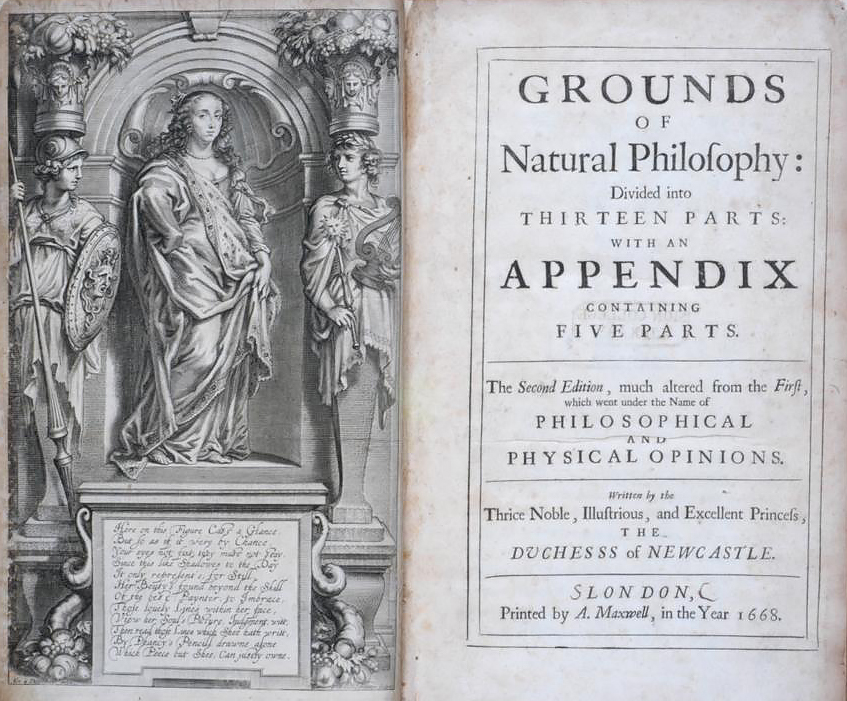

By the time of her death in 1673, Cavendish had developed an overarching position that was unique in the philosophical landscape of her time. Her philosophical views are presented in her works Poems and Fancies (1653), Philosophical Fancies (1653), Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1655), Philosophical Letters (1664), Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy (1666), and Grounds of Natural Philosophy (1668), among others. In her works, she discusses Cartesian dualism, the materialism of Hobbes, and mechanist views of nature and of causation. According to many scholars, Cavendish staked out a new position that was distinguished from both the dualism and the materialism of her contemporaries.

For image sources and permissions, see our image gallery.

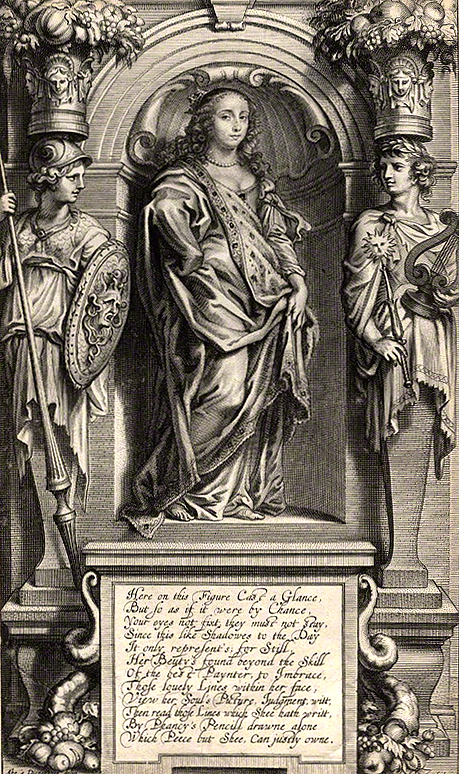

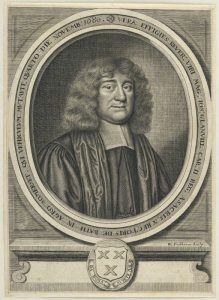

1.2 Portraits

Cavendish’s publications stand out not only because of their number (thirteen in total), but also because they visually represent a campaign of public self-promotion rare among women authors of the time. Cavendish not only self-published lavish presentation volumes, but she had many of the frontispieces engraved with her portraits – leaving no one in doubt as to the author. Unlike Conway and Masham, who cultivated socially acceptable anonymity, she unabashedly sought publicity.

Historical context

To put Cavendish’s publications in context, in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the number of women whose works were published in print increased to the hundreds. However, most of these works were not published in quarto or folio format – what we would today think of as “book” and “large book” formats. According to Jane Stevenson, “well over half of seventeenth-century women’s ventures into print – approximately 60% – belong to the level of printing which was only one step up from the broadsheet ballad: pamphlets which amounted to one or one-and-a-half sheets cut and folded.” (Stevenson, 2009, pg. 207)

This would not do for Cavendish. As a wealthy aristocrat, she did not need to publish for financial gain; rather, self-published in order to gain widespread recognition from philosophers and academics. To give her works respectability, she published them in a format expected for scholarly works, the kind that would be included in university libraries, and commissioned the best possible publishers, printers, and illustrators. She published her first six works with the upscale London publishers John Martin and James Allestrye, who worked with some of the best printers, such as T. Roycroft. It is not clear why, but in 1662 Cavendish decided to work directly with a different printer, William Wilson, and after 1666, with the Anne Maxwell. Her works were published in the large folio format, which was usually reserved for classical authors, Bibles, or theological works.

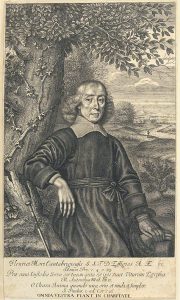

Abraham Van Diepenbeeck

Moreover, Cavendish commissioned multiple portrait frontispieces for her works from Abraham Van Diepenbeeck (1596-1675) a Dutch stained-glass painter, painter and illustrator. Today he has been largely forgotten and is remembered in association with the Dutch painter Peter Paul Rubens. Van Diepenbeeck was familiar with Rubens’s work and produced a number of engravings based on his paintings. When he was rediscovered in the 19th century, many of the copies of Rubens’s paintings were attributed to him. Van Diepenbeeck was, however, a painter in his own right, although it is difficult to track down all his paintings and drawings (research forthcoming). It is not clear why Cavendish settled on Van Diepenbeeck; perhaps there is a personal connection: during their exile in Antwerp, Cavendish and her husband Sir William stayed in a house formerly owned by Rubens. Sir William also commissioned Van Diepenbeeck to draw family portraits, one of which is included in Cavendish’s works as a frontispiece, and to draw several illustrations for his publication on horse dressage, La Méthode Nouvelle et Invention Extraordinaire de Dresser les Chevaux (1658).

Image of Van Diepenbeeck forthcoming.

Van Diepenbeeck individual portraits

(1) Image of the Minerva & Apollo portrait, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Multiple portraits by Van Diepenbeeck appear in many of Cavendish’s works. One is a picture of Cavendish in “which she appears as a classical heroine, standing in a masculine heroic pose with hand on hip, elbow pointed towards the viewer, draped in loose robes, wearing sandals, and standing in a statue’s niche between herms of Minerva and Apollo, who turn their heads in her direction. Marchioness Sappho, so to say.” (Stevenson, 2009, pg. 212). The portrait was engraved by Pieter Louis van Schuppen, after Abraham Diepenbeeck, and appears in six of the works digitized in the Early English Books Online proprietary database (EEBO).

The inscription below the portrait states:

(2) Image of the Scholar portrait, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Another portrait is “as Scholar Marchioness: she sits by her writing table, wearing a plain dark dress, a feminine equivalent of scholar’s black, though she also wears a marchioness’s coronet, while a fine carriage clock takes the place of the hourglass used in scholars’ portraits to indicate that time is being well used. A cloth of state hangs above her, and in front of her, separating her from the viewer, is a low balustrade, such as was used to divide the monarch or aristocrat on his dais from the rest of the room.” (Stevenson, 2009, pg. 212) It is not clear who was the engraver of this image. Note: Unfortunately this portrait does not appear in any of digitized copies of Cavendish’s works available in EEBO. Perhaps it appears in different copies (research forthcoming).

Other individual portraits

The National Portrait Gallery’s website indicates that there are at least three other extant portraits, engraved after Van Diepenbeeck:

(3) Seated portrait, engraver unknown. This portrait appears in two of the works on EEBO. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery in London (two copies).

(4) Draped robe standing portrait, various engravers. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery in London (three copies).

(5) Court dress with pillar standing portrait, by William Greatbach, after Abraham Diepenbeeck. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery in London (two copies.)

Van Diepenbeeck – family portraits

There are also four group family portraits engraved after drawings by Van Diepenbeeck, some of which also serve as frontispieces. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

(6) The Duke and his family, by Peter van Lisebetten (Lysebetten, Liesebetten), after Abraham Diepenbeeck.

(7) William & Margaret Cavendish seated, by Peter van Lisebetten (Lysebetten, Liesebetten), after Abraham Diepenbeeck.

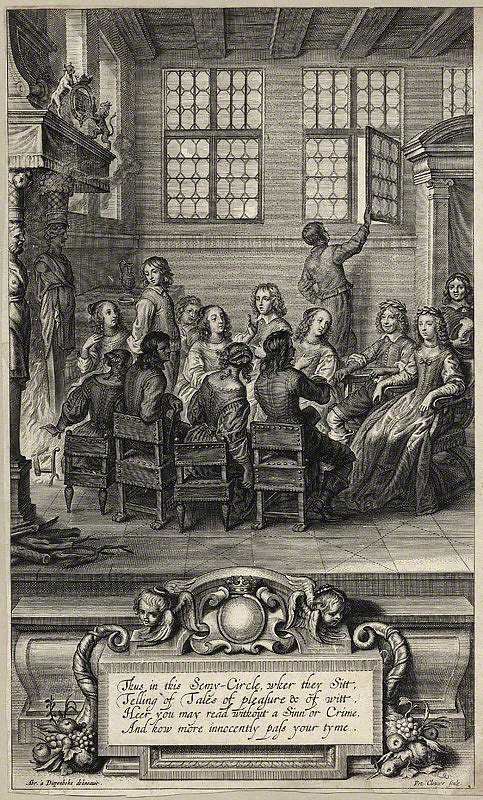

(8) The Duke and his family in Antwerp, by Peeter Clouwet, after Abraham Diepenbeeck. This portrait appears once in Cavendish’s works in EEBO.

The inscription below the picture states:

(9) William & Margaret Cavendish, small seated picture, by James Mitan, after Peeter Clouwet.

Painted portraits

The portrait on our website is by Gonzales Coques, and is called “Portrait of a Married Couple in a Park,” or “Lord Cavendish und Seine Frau Margaret im Rubensgarten in Antwerpen” (Kat.Nr. 858). The image is reproduced here with the permission of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. Foto: Jörg P. Anders.

To date, we have been able to identify two additional possible painted portraits. One is attributed to Sir Peter Lely, but many scholars suggest that this is a painting of Cavendish’s oldest sister. Another one is attributed to Van Diepenbeeck, and was reproduced in Grant’s (1957) biography by the permission of the Duke of Portland, K.G.

List of portraits & frontispieces in Early English Books Online

Note: the following information is from digitized copies of originals available in the Early English Books Online proprietary database. First editions are in bold. There may be other copies of Cavendish’s work with different portraits or frontispieces.

Spreadsheet version of table: Excel file

|

Source |

Year |

Portrait |

Frontispiece |

Source library |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Philosophical Fancies |

1653

|

— |

London. Printed by Tho. Roycroft for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church-yard. |

British Library |

|

Poems and Fancies |

1653

|

Minerva & Apollo (1)

|

London. Printed by T. R. for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church Yard. |

Huntington Library |

|

Philosophical and Physical Opinions

|

1655 |

Grant (1957) cites Scholar portrait (2) but this is not in EEBO.

|

London. Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church-Yard. |

British Library |

|

The World’s Olio |

1655 |

Minerva & Apollo (1)

|

London. Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church-Yard. |

Huntington Library |

|

Nature’s Pictures |

1656

|

Duke and his family in Antwerp (8)

|

London. Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church-Yard. |

Huntington Library |

|

Orations of Divers Sorts

|

1662 |

— |

London. Printed Anno Dom. (1663 in Latin) |

Cambridge University |

|

Plays |

1662

|

Minerva & Apollo (1)

|

London. Printed by A. Warren for John Martyn, James Allestry, and Tho. Dicas, at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church Yard. |

Huntington Library |

|

Orations of Divers Sorts

|

1663 |

— |

London. Printed Anno Dom. 1663. |

University of Durham, England |

|

Philosophical and Physical Opinions

|

1663 |

— |

London: Printed by William Wilson. |

Huntington Library |

|

Sociable Letters |

1664

|

— |

London: Printed by William Wilson. |

Harvard University Library |

|

Philosophical Letters |

1664

|

— |

London. Printed in the year 1664. |

Cambridge University Library |

|

Poems and Fancies

|

1664 |

— |

London: Printed by William Wilson. Anno Dom. (1664 in Latin) |

Huntington Library |

|

Observations upon Experimental Philosophy & The Blazing World |

1666 |

— |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1666. |

University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) |

|

The Blazing World |

1666 |

— |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1666. |

Harvard University Library |

|

The Life of William |

1667 |

— |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1667. |

University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign Campus) |

|

The Blazing World

|

1668 |

Seated portrait (3) |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year (1668 in Latin.) |

British Library |

|

Grounds of Natural Philosophy (revised 3rdedition of Philosophical and Physical Opinions) |

1668 |

Image not available in EEBO. |

Image not available in EEBO. |

Huntington Library |

|

Observations upon Experimental Philosophy & The Blazing World |

1668 |

— |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1668. |

Cambridge University Library |

|

The Blazing World |

1668 |

Seated portrait (3) |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year (1668 in Latin.) |

British Library |

|

Orations of Divers Sorts

|

1668 |

— |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1668. |

Edinburgh University Library |

|

Plays, Never Before Printed

|

1668

|

Minerva & Apollo (1)

|

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year (1668 in Latin.) |

Huntington Library |

|

Poems and Fancies, or Several Fancies In Verse

|

1668 |

Minerva & Apollo (1) Court dress (5)

|

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1668. |

Huntington Library |

|

Nature’s Pictures

|

1671 |

Minerva & Apollo (1)

|

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1671. |

British Library |

|

The World’s Olio

|

1671 |

— |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1671. |

Huntington Library |

|

The Life of William

|

1675 |

Portrait of William. |

London: Printed by A. Maxwell, in the Year 1675. |

Huntington Library |

National Portrait Gallery, London

The National Portrait Gallery main link for Van Diepenbeeck’s portraits of Cavendish.

References

Grant, Douglas. 1957. Margaret the First; a biography of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, 1623-1673: London, Hart-Davis, 1957. (See illustrations page in front matter.)

Steadman, David W. 1982. Abraham Van Diepenbeeck: Seventeenth Century Flemish Painter. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

Stevenson, Jane. 2009. “Women and the Cultural Politics of Printing.” The Seventeenth Century 24 (2): 205-237.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.3 Chronology

Source: For more details, see the very helpful account of the major dates and events in Cavendish’s life in O’Neill, Eileen, editor, 2001. Margaret Cavendish: Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. xxxvii-xli.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| c. 1623 | Margaret Lucas, youngest of eight children of Thomas Lucas and Elizabeth Leighton Lucas, born in Colchester, England. |

| 1625 | Death of Cavendish’s father, Thomas. |

| 1630 | Hobbes begins teaching natural philosophy to William Cavendish, Earl of Newcastle, and to William’s brother, Charles. |

| 1635-36 | Hobbes joins Marin Mersenne’s scholarly circle in Paris, which maintained contact with Descartes. |

| 1641 | Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy published in Latin. |

| 1642 | Looters enter Cavendish’s home in St. John’s Abbey as the English Civil War begins. |

| 1643 | Cavendish becomes a maid of honor to Queen Henrietta Maria, who had fled from anti-Royalist forces in London to Merton College in Oxford.

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia enters into a now famous correspondence with Descartes, challenging his dualism of mind and body. |

| 1644 | Descartes’s Principles of Philosophy, Mersenne’s Synopsis of Universal Geometry and Mixed Mathematics and Physico-Mathematical Thoughts, and Kenelm Digby’s Two Treatises, are all published. Descartes’s Principles would be seen as his magnum opus in natural philosophy, and was translated into French three years later.Cavendish follows Queen Henrietta Maria into exile in Paris. |

| 1645 | Cavendish’s future husband William travels in the Netherlands and visits the exiled Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia in The Hague; he later arrives in Paris, where he meets and corresponds with Cavendish. William and Margaret marry at year’s end in Sir Richard Browne’s chapel, thereby changing Margaret’s life forever. |

| 1647 | Death of Cavendish’s sister, Mary Killigrew; her mother, Elizabeth Leighton Lucas; and her illegitimate brother, Sir Thomas. |

| 1648 | Mersenne dies. Cavendish and her husband William travel to Holland following King Charles I, renting rent the house formerly owned by the famous painter, Peter Paul Rubens, in Antwerp.Parliamentary troops execute William Cavendish’s brother, Sir Charles. |

| 1649 | King Charles I is executed in London. |

| 1650 | During his time in Stockholm tutoring Queen Christina, who would later become an important figure for thinkers like Émilie Du Châtelet, Descartes dies. Hobbes published his The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic.

Walter Charleton publishes some medical treatises of J. B. Van Helmont, in his A Ternary of Paradoxes. |

| 1651 | Hobbes publishes what would become his most famous and influential work, Leviathan. |

| 1652 | Walter Charleton publishes his The Darknes of Atheism Dispelled by the Light of Nature. |

| 1653 | Henry More’s An Antidote Against Atheisme and the first English edition of William Harvey’s On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals are both published.

Cavendish publishes her very first volume, Poems, and Fancies, followed quickly by Philosophicall Fancies a few months later. She returns from her trip to England back to Antwerp. |

| 1654 | Charleton’s Physiologia-Epicuro-Gassendo-Charltoniana is published, an influential work that would be read by many natural philosophers, including a young Isaac Newton.Death of Charles Cavendish. |

| 1655 | Cavendish’s shorter literary pieces, including Shakespeare criticism and her discussion of Harvey on the circulation of the blood, are published as The World’s Olio.Also published are Cavendish’s Philosophical and Physical Opinions, and Hobbes’ Latin treatise, Elements of Philosophy, The First Section Concerning Body, which was published in an English translation in 1656.

Death of Pierre Gassendi. |

| 1656 | Cavendish publishes Nature’s Pictures, which includes her biographical essay ‘‘A True Relation of My Birth, Breeding and Life.” |

| 1657 | Cavendish corresponds with Constantijn Huygens, father of the mathematician and philosopher Christiaan, who would become renown throughout Europe later in the century. |

| 1658 | William Cavendish publishes a French work, The New Method and Extraordinary Invention to Dress Horses and Work Them According to Nature. |

| 1659 | Henry More publishes The Immortality of the Soul; More would eventually become connected with the philosopher Anne Conway. |

| 1660 | Charles II is restored to the throne.Cavendish and her husband William return from exile, residing at Welbeck Abbey, an estate in Nottingham. She becomes an honorary member of the literary salon of Katherine Philips. Robert Boyle publishes his famous New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall, touching the Spring of the Air and Its Effects; we have reproduced a diagram from this work in the Images section of the site. |

| 1662 | Cavendish’s Playes and Orations of Divers Sorts, as well as Johannes Baptista Van Helmont’s Oriatrike, Or, Physick Refined are published. |

| 1663 | A revised version of Cavendish’s Philosophical and Physical Opinions and Henry Power’s Experimental Philosophy are both published. |

| 1664 | Henry More discusses Cavendish in his letter of March 1664/65 to Conway. |

| 1665 | Robert Hooke, a former assistant to Boyle and later the Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society, publishes his Micrographia, which is often considered a neglected work of this period.

William Cavendish is made Duke of Newcastle. |

| 1666 | Cavendish publishes her Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, to which is added, the Description of a New Blazing World.Margaret Cavendish’s eldest brother, John, is expelled from the Royal Society of London |

| 1667 | Cavendish’s The Life of the Thrice Noble . . . William Cavendishe is published, with a Latin translation published by Walter Charleton in 1668.Cavendish corresponds with Glanvill on metaphysical issues and also visits the Royal Society of London. |

| 1668 | Cavendish’s Grounds of Natural Philosophy and Plays, never before Printed are both published |

| 1673 | Cavendish dies on December 15 – she is buried in Westminster Abbey on January 7 of the next year. |

| 1676 | William Cavendish edits and publishes Letters and Poems in Honour of the Incomparable Princess, Margaret, Dutchess of Newcastle.Death of William – he is buried next to Margaret in Westminster Abbey. |

2. Primary Sources Guide

Cavendish delighted in publicizing her work: unlike her fellow English philosophers Conway and Masham, she insisted on having her name, and usually a portrait, printed in her works. Given that she was a prolific writer, we have tried to breakdown the information on primary sources in a helpful way. Section 2.1 provides a chronological reference list of Cavendish’s published works, a breakdown of the references according to specific work and its editions, and a list of modern editions. Section 2.2 provides a brief description of each of her works.

There is no standard critical edition of Cavendish’s complete works, and few of her writings are available in their entirety in modern editions. However, digital scans of the originals of all her works are available electronically through the Early English Books Online (proprietary) database. It also makes available modern text transcriptions of all the first editions of the texts.

An annotated list of Cavendish’s texts, printers, and booksellers (1653-1675) has been compiled by Cameron Kroetsch and is available for download as a PDF on the Digital Cavendish Project website.

Spreadsheet overview: Excel file

2.1 Primary Sources

Chronological list

Cavendish, Margaret. 1653. Philosophicall Fancies. London: Printed by Tho. Roycroft for J. Martin and J. Allestrye.

______. 1653. Poems and Fancies. London: Printed by T. Roycroft for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church Yard.

______. 1655. Philosophical and Physical Opinions. London: Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in St. Pauls Church-Yard.

______. 1655. The World’s Olio. London: Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye.

______. 1656. Nature’s Pictures Drawn by Fancie’s Pencil to Life. London: Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Paul’s Church-yard.

______. 1662. Orations of Divers Sorts, Accommodated to Divers Places. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1662. Playes. London: Printed by A. Warren for John Martyn, James Allestry, and Tho. Dicas, at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church Yard.

______. 1663. Orations of Divers Sorts, Accommodated to Divers Places. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1663. Philosophical and Physical Opinions. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1664. CCXI Sociable Letters. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1664. Philosophical Letters. London: Publisher unknown.

______. 1664. Poems and Fancies. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1666. The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1666. Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. To Which is Added, the Description of a New Blazing World. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1667. The Life of the Thrice Noble, High and Puissant Prince William Cavendishe, Duke, Marquess, and Earl of Newcastle. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. Grounds of Natural Philosophy. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. To Which is Added, the Description of a New Blazing World. 2nd ed. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. Orations of Divers Sorts, Accommodated to Divers Places. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. Playes, Never Before Printed. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. Poems, or Several Fancies in Verse: with the Animal Parliament, in Prose… The Third Edition. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1671. Nature’s Pictures Drawn by Fancie’s Pencil to Life. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1671. The World’s Olio. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1675. The Life of the Thrice Noble, High and Puissant Prince William Cavendishe, Duke, Marquess, and Earl of Newcastle. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Contemporary Latin edition of the Life of William

Charleton, William, ed. 1668. De Vita et Rebus Gestis…Guilielmi Ducis Novo-Castrensis. London: Printed by T. Milbourne.

Contemporary review of Cavendish’s work

Du Verger, S. 1657. Humble Reflections upon some passages of the Right Honorable the Lady Marchionesse of Newcastles Olio, or, An Appeale from her Mes-informed, to her Owne Better Informed Judgement. Printed at London: Publisher unknown.

Early English Books Online database, Gale Group, has a modern text transcript and images of the 1657 original in the Huntington Library.

O’Neill cites this work as the only published contemporary critical response. Reference: O’Neill, Eileen. 2001. Margaret Cavendish: Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

List of editions, by work in alphabetical order

Blazing World

Cavendish, Margaret. 1666. The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

The Life of William

Cavendish, Margaret. 1667. The Life of the Thrice Noble, High and Puissant Prince William Cavendishe, Duke, Marquess, and Earl of Newcastle. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Charleton, William, ed. 1668. De Vita et Rebus Gestis…Guilielmi Ducis Novo-Castrensis. London: Printed by T. Milbourne.

Cavendish, Margaret. 1675. The Life of the Thrice Noble, High and Puissant Prince William Cavendishe, Duke, Marquess, and Earl of Newcastle. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Philosophical Fancies

Cavendish, Margaret. 1653. Philosophicall Fancies. London: Printed by Tho. Roycroft for J. Martin and J. Allestrye.

Philosophical and Physical Opinions (later renamed Grounds of Natural Philosophy)

Cavendish, Margaret. 1655. Philosophical and Physical Opinions. London: Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in St. Pauls Church-Yard.

______. 1663. Philosophical and Physical Opinions. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1668. Grounds of Natural Philosophy. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Plays & Plays Never Before Printed

Cavendish, Margaret. 1662. Playes. London: Printed by A. Warren for John Martyn, James Allestry, and Tho. Dicas, at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church Yard.

______. 1668. Playes, Never Before Printed London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Poems and Fancies

Cavendish, Margaret. 1653. Poems and Fancies. London: Printed by T. Roycroft for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Pauls Church Yard.

______. 1664. Poems and Fancies. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1668. Poems, or Several Fancies in Verse: with the Animal Parliament, in Prose…The Third Edition. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Nature’s Pictures

Cavendish, Margaret. 1656. Nature’s Pictures Drawn by Fancie’s Pencil to Life. London: Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye at the Bell in Saint Paul’s Church-yard.

______. 1671. Nature’s Pictures Drawn by Fancie’s Pencil to Life. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy

Cavendish, Margaret. 1666. Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. To Which is Added, the Description of a New Blazing World. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

______. 1668. Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. To Which is Added, the Description of a New Blazing World. 2nd ed. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Orations of Divers Sorts

Cavendish, Margaret. 1662. Orations of Divers Sorts, Accommodated to Divers Places. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1663. Orations of Divers Sorts, Accommodated to Divers Places. London: Printed by William Wilson.

______. 1668. Orations of Divers Sorts, Accommodated to Divers Places. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Philosophical Letters

Cavendish, Margaret. 1664. Philosophical Letters. London: Publisher unknown.

Sociable Letters

Cavendish, Margaret. 1664. CCXI Sociable Letters. London: Printed by William Wilson.

The World’s Olio

Cavendish, Margaret. 1655. The World’s Olio. London: Printed for J. Martin and J. Allestrye.

______. 1671. The World’s Olio. London: Printed by A. Maxwell.

Modern editions of Cavendish’s work

Please note that this list is not exhaustive. Excerpts of Cavendish’s works have been published in many modern works, especially literary anthologies. Cavendish remains a popular literary author. The following list focuses on complete modern editions of her work, along with works that include her natural philosophy.

Atherton, Margaret, ed. 1994. Women Philosophers of the Early Modern Period. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Note: Contains selections from Philosophical Letters.

Cavendish, Margaret. 1969. CCXI Sociable Letters (Facsimile Reprint). Menston: Scolar Press.

______. 1972. Poems and Fancies (Facsimile Reprint). Menston: Scolar Press.

De Longueville, Thomas, ed. 1910. The first Duke and Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. London; New York: Longmans, Green.

Firth, C. H., ed. 1886. The Life of William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle, to Which is Added the True Relation of my Birth, Breeding and Life. London: New York: Scribner & Wellford.

______, ed. 1903. The Cavalier in Exile; Being the Lives of the First Duke & Dutchess of Newcastle . London: G. Routledge & sons limited.

______, ed. 1906. The Life of William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle, to Which is Added the True Relation of my Birth, Breeding and Life . London: G. Routledge.

______, ed. 1915. The Life of the First Duke of Newcastle: and other writings. London: G. Routledge.

Fitzmaurice, James, ed. 1997. Margaret Cavendish: Sociable Letters . New York: Garland.

James, Susan, ed. 2003. Margaret Cavendish: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lilley, Kate, ed. 1923. The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World and Other Writings. New York: New York University Press.

______, ed. 1992. The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World and Other Writings. New York: New York University Press.

______, ed. 1994. The Blazing World and Other Writings. London: Penguin.

Lower, Mark Antony, ed. 1872. The Lives of William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle, and of his Wife, Margaret, Duchess of Newcastle. London: J. R. Smith.

Michael, Colette V. , ed. 1996. Grounds of Natural Philosophy (Facsimile Reprint). West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill Press.

O’Neill, Eileen, ed. 2001. Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rhys, Ernest, ed. 1915. The Life of the Duke of Newcastle. London; New York: J.M. Dent; E.P. Dutton.

______, ed. 1916. The Life of the (1st) Duke of Newcastle, & Other Writings. London; Toronto; New York: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd.; E.P. Dutton & Co.

Shaver, Anne, ed. 1999. The Convent of Pleasure and Other Plays. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

2.2. Primary Sources Description

Cavendish was a prolific writer, composing thirteen works of varied genre, including poems, plays, fiction, orations, letters and philosophical essays. It can be a challenge to keep track of the different works, editions, and their content. Below is an overview of the content of her works. Since scholars differ in their interpretations of the works – for example, there is not a consensus on exactly which ones contain her “natural philosophy” – the descriptions are brief. The overview table in this section lists the first editions, and subsequent editions only where a work underwent major revision.

Helpful resources regarding Cavendish’s specific works include:

Stewart Duncan’s overview of the Philosophical Letters (1664)

Table of contents and sources link.

Cross-listed at The Digital Cavendish Project.

A handful of the letters are reproduced online here.

Emory Women Writers Resource Project digital edition of the atomic poems included in the first fifty or so pages of Poems and Fancies (1653):

Digital edition can be found here.

Critical introduction to digital edition can be found here.

‘The Language of Genres’ data analysis of Cavendish’s texts by Jacob Tootalian, PhD candidate in English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, can be found on the Digital Cavendish Project website.

Articles which summarize the content of Cavendish’s works on natural philosophy:

Boyle, Deborah. 2004. “Margaret Cavendish’s Nonfeminist Natural Philosophy.” Configurations: A Journal of Literature, Science, and Technology 12 (2): 195-227.

James, Susan, ed. 2003. Margaret Cavendish: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (A critical edition of The Blazing World and Orations.)

Descriptions of Cavendish’s works

|

Source |

Year |

Brief description |

|---|---|---|

| Poems and Fancies | 1653

|

A collection of poems, epistles and some prose on a variety of topics. It is notable because the first fifty pages contain poems on atoms, and offer atomistic explanations of various natural phenomena such as cold, life, death, frost, etc. Various other topics include animals, the sun, roaring of the sea, witches of Lapland, battle between life and death, love, passions, etc.

Emory Women Writers Resource Project digital edition of the atomic poems. |

| Philosophical Fancies | 1653

|

A collection of short thoughts and verse on natural and other topics such as: matter, nature, infinite knowledge, vacuum, division, pleasure, senses, thinking, animals, optics, planets, etc. |

| The World’s Olio

|

1655 | Note: the term ‘olio’ means a ‘miscellaneous collection of things.’

A collection of short essays on a variety of social topics such as fame, why men write books, translating, languages, music, dancing, virtues and vices, mind and body, riches and poverty, etc. It contains references to various historical and mythological figures. |

| Philosophical and Physical Opinions

|

1655 | Offers explanations of various natural phenomena such as life, death, growth, passions, light, earth, water, air, fire, and diseases, in terms of motion as well as in non-mechanistic terms. The work also discusses variety in nature and the possibility of our knowledge of nature. The front matters includes the Condemning Treatise of Atomes, which is sometimes interpreted as a rejection her earlier atomistic views. |

| Nature’s Pictures

|

1656

|

A collection of stories in verse, prose and dialogues mostly on the topic of love, in which Cavendish discusses the position of women in society. She also satirizes the use of tobacco. The first edition (but not the second 1671 edition) contains an autobiographical letter titled ‘A True Relation of my Birth, Breeding and Life.’ |

| Plays | 1662

|

The first collection of plays includes fourteen pieces, many of which comment on the position of women in society:

Loves Adventures The Several Wits Youths Glory, and Death’s Banquet The Lady Contemplation Wits Cabal The Unnatural Tragedy The Public Wooing The Matrimonial Trouble Nature’s Three Daughters, Beauty, Love and Wit The Religious The Comical Hash Bell in Campo A Comedy of the Apocryphal Ladies The Female Academy |

| Orations of Divers Sorts

|

1662 | A collection of oratory speeches which present multiple opposing views on subjects to do with a fictional society which is on the brink of civil war. The orations take up subjects such as the pros and cons of peace and war, the levying of taxes, theft, adultery, and virtues appropriate to private and public life. Some of the orations also explore the position of women in society, and discuss the reasons for women’s subordinate position to men, including their lack of educational opportunities. |

| Philosophical and Physical Opinions | 1663 | This is a major revision of Cavendish’s earlier work of the same title. The 1655 first edition is 174 pages, but the 1663 edition is 510 pages including the prefaces and index. To read an open access version of this text, see Margaret Cavendish: Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1663 edition), edited by Marcy Lascano. |

| Sociable Letters | 1664

|

A collection of fictional and partly auto-biographical letters between two gentlewomen. The witty letters discuss a variety of social topics from daily life, notably love and the institution of marriage. The work is often interpreted as a critique of marriage. |

| Philosophical Letters | 1664

|

The work presents Cavendish’s natural philosophy and engages with the ideas of Hobbes, Descartes, Henry More, J.B. Van Helmont, and other seventeenth-century philosophers such as Robert Boyle and William Harvey. For example, Cavendish discusses their mechanical explanations of perception, light and colors, the view that motion can be transferred, and their views on immaterial substances. She also discusses the limits of human knowledge. The work is often interpreted as a critical response to these philosophers.

Stewart Duncan’s overview of the Letters: Table of contents and sources link Cross-listed at The Digital Cavendish Project A handful of the letters are reproduced online here |

| Observations upon Experimental Philosophy

|

1666 | The work discusses the mechanical, corpuscular and experimental philosophy promoted by the Royal Society, and the use of new instruments such as microscopes and telescopes. It is often interpreted as a direct critique of the Royal Society’s work, especially Robert Hooke’s Micrographiaand Robert Boyle’s experiments. The work also discusses mechanistic explanations of natural phenomena and atomism.

Some scholars suggest that the Observations and The Blazing World, which were initially published together, should be viewed as philosophical companion pieces despite their different genres. |

| The Blazing World

(published with Observations)

|

1666

|

A fictional sci-fi utopia, which tells a story of a woman who is abducted from her world and becomes the Empress of a different world, where she proceeds to set up learned societies, study immaterial spirits, and wage futuristic-style warfare back in her own world. The Duchess of Newcastle acts as an adviser to the Empress. The work is considered a forerunner of science fiction, and is often interpreted as a satire of the Royal Society and the irrelevance of its methods for effective political governance. |

| The Life of William

|

1667 | A biography of her husband, William Cavendish, the first Duke of Newcastle. The biography became very popular and was reprinted several times. |

| Plays, Never Before Printed

|

1668

|

The second collection of plays consists of six new pieces. Like her first collection of plays, the second set comments on women’s’ position in society. Many of them also poke fun at the dashing ‘rake’ lover ideal of the Restoration period.

The Sociable Companions, or the Female Wits The Presence Scenes (edited from The Presence) The Bridals The Convent of Pleasure A Piece of a Play |

| Grounds of Natural Philosophy

(3rd edition of Philosophical and Physical Opinions)

|

1668 | A revised second edition of Philosophical and Physical Opinions. The work, split into thirteen sections, presents Cavendish’s view on natural philosophy and its implications for a variety of natural phenomena, such as perception, animal and human reproduction, appetites and passions, human dreams, illness, etc. It also discusses natural phenomena such as fire, tides, wind, the motions of the planets, etc.

The work includes five appendices on the topics of immaterial spirits, possibility of other worlds, happiness of creatures, natural conditions in an irregular world, and the possibility of resurrection by means of restoring beds or ‘wombs.’ |

3. Secondary Sources Guide

The following reference list focuses on scholarship that is most relevant to philosophy. The list is by no means exhaustive, as Cavendish is a very popular figure in many humanistic disciplines and the scholarly literature is vast. A critical treatise of Cavendish’s philosophy from an analytic philosophy perspective has not yet been published, although new scholarship is forthcoming.

Bibliographies

For extensive bibliographies categorized according to topic, please consult the following resources:

James, Susan, ed. 2003. Margaret Cavendish: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press. (See pp. xxxiv-xxxix of the Introduction)

O’Neill, Eileen. 2001. Margaret Cavendish: Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (See Further Reading, pp. xlii-xliv.)

Weise, Wendy. 2012. “Recent Studies in Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (2001-2010).” English Literary Renaissance 42 (1): 146-176.

The Margaret Cavendish Bibliography Initiative of the International Margaret Cavendish Society, maintained by graduates at Brigham Young University since 2012.

Introductory resources

Some introductory resources for students and instructors who are just starting to explore Cavendish’s natural and political philosophy are:

Chapter in Jacqueline Broad’s Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century (2002)

David Cunning’s article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Introduction by Susan James to her edition of Margaret Cavendish: Political Writings (2003)

Introduction by Eileen O’Neill to her edition of Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy (2001)

Lisa Sarasohn’s book The Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish: Reason and Fancy During the Scientific Revolution (2010)

Edited collections

Two recent edited collections include essays on various aspects of Cavendish’s life and work, including her natural philosophy:

Stephen Clucas, A Princely Brave Woman: Essays on Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle(2003)

Sara Mendelson, Margaret Cavendish (2009)

3.1 Secondary Sources

Selected reference works & encyclopedia articles

Knight, Joseph. 1917. “Cavendish, Margaret.” In The Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 3, edited by Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Neill, Eileen. “Cavendish, Margaret Lucas (1623-1673).” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. 1, edited by E. Craig.

Schiebinger, Londa. 1987. “Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle: Natural Philosopher (1617-1673).” Resources for Feminist Research 16 (3).

______. 1991. “Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle.” In Modern Women philosophers, 1600-1900, Vol. 3, edited by Mary Ellen Waithe. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Selected secondary sources in philosophy

Alic, Margaret. 1986. “The Rise of the Scientific Lady.” In Hypatia’s Heritage: a History of Women in Science from Antiquity Through the Nineteenth Century, edited by Margaret Alic. Boston: Beacon Press.

Ankers, Neil. 2000. “Margaret Cavendish and the Nature of the Individual.” In-between: Essays and Studies in Literary Criticism 9 (1-2): 301-315.

______. 2003. “Paradigms and Politics: Hobbes and Cavendish Contrasted ” In A Princely Brave Woman: Essays on Margaret Cavendish, edited by Stephen Clucas. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Apostalova, Iva. 2010. “Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia and Margaret Cavendish: The Feminine Touch in Seventeenth-Century Epistemology.” Maritain Studies/Etudes Maritainiennes 26: 83-97.

Barnes, Diana. 2009. “Familiar Epistolary Philosophy: Margaret Cavendish’s Philosophical Letters (1664).” Parergon: Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association for Medieval and Early Modern Studies 26 (2): 39-64.

Battigelli, Anna. 1998. Margaret Cavendish and the Exiles of the Mind, Studies in the English Renaissance. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

______. 1998. “Political thought/political action: Margaret Cavendish’s Hobbesian dilemma.” In Women Writers and the Early Modern British Political Tradition, edited by Hilda L. Smith and Carole Pateman. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Bertuol, Roberto. 2001. “The Square Circle of Margaret Cavendish: the 17th Century Conceptualization of Mind by Means of Mathematics.” Language and Literature 10 (1): 21-39.

Blaydes, Sophia B. 1988. “Nature Is a Woman: The Duchess of Newcastle and Seventeenth-Century Philosophy.” In Man, God, and Nature in the Enlightenment, edited by Donald C. Mell, Jr., Theodore E. D. Braun and Lucia M. Palmer. East Lansing, MI: Colleagues.

Bordo, Susan. 1999. “Women Cartesians, ‘Feminine Philosophy,’ and Historical Exclusion.” In Feminist Interpretations of René Descartes, edited by Susan Bordo. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Borlik, Todd. 2008. “The Whale under the Microscope: Technology and Objectivity in Two Renaissance Utopias.” In Philosophies of Technology: Francis Bacon and His Contemporaries, edited by Claus Zittel, Gisela Engel, Romano Nanni and Nicole C. Karafyllis. Leiden: Brill.

Boyle, Deborah. 2004. “Margaret Cavendish’s Nonfeminist Natural Philosophy.” Configurations: A Journal of Literature, Science, and Technology 12 (2): 195-227.

______. 2006. “Fame, Virtue, and Government: Margaret Cavendish on Ethics and Politics.” Journal of the History of Ideas 67 (2): 251-289.

______. 2013. “Margaret Cavendish.” Philosophers’ Magazine 60 (1): 63 – 65.

______. 2013. “Margaret Cavendish on Gender, Nature, and Freedom.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 28 (3): 516-532.

Broad, Jacqueline. 2002. Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

______. 2007. “Margaret Cavendish and Joseph Glanvill: Science, Religion, and Witchcraft.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 38 (3): 493-505.

______. 2011. “Cavendish, Van Helmont and the Mad Raging Womb.” In The New Science and Women’s Literary Discourse: Prefiguring Frankenstein, edited by Judy A. Hayden. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

______. 2011. “Is Margaret Cavendish Worthy of Study Today?” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 42 (3): 457-461.

______. 2012. “Impressions in the Brain: Malebranche on Women, and Women on Malebranche.” Intellectual History Review 22 (3): 373-389.

Broad, Jacqueline, and Karen Green. 2009. “Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle.” In A History of Women’s Political Thought in Europe, 1400-1700, edited by Jacqueline Broad and Karen Green. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clairhout, Isabelle, and Sandro Jung. 2011. “Cavendish’s Body of Knowledge.” English Studies: A Journal of English Language and Literature 92 (7): 729-743.

Clucas, Stephen. 1994. “The Atomism of the Cavendish Circle: a Reappraisal.” The Seventeenth Century 9: 247–273.

______. 2000. “The Duchess and the Viscountess: Negotiations between Mechanism and Vitalism in the Natural Philosophies of Margaret Cavendish and Anne Conway.” In-between: Essays and Studies in Literary Criticism 9 (1-2): 125-136.

______, ed. 2003. A Princely Brave Woman: Essays on Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. Aldershot: Ashgate.

______. 2003. “Variation, Irregularity, and Probabilism: Margaret Cavendish and Natural Philosophy as Rhetoric.” In A Princely Brave Woman: Essays on Margaret Cavendish, edited by Stephen Clucas. Aldershot: Ashgate.

______. 2011. “Margaret Cavendish’s Materialist Critique of Van Helmontian Chymistry.” Ambix 58 (1): 1-12.

Correard, Nicolas. 2013. “Anti-Scientific Scepticism and Early Satires of the Royal Society: Exposing the Fictions of Experimental Science in Samuel Butler, Margaret Cavendish and Jonathon Swift (1660-1730).” Science et Esprit: Revue de philosophie et de théologie 65 (3): 325-342.

Cottegnies, Line, and Nancy Weitz, eds. 2003. Authorial conquests : essays on genre in the writings of Margaret Cavendish. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; Associated University Presses.

Cunning, David. 2006. “Cavendish on the Intelligibility of the Prospect of Thinking Matter.” History of Philosophy Quarterly 23 (2): 117-136.

______. 2012. “Margaret Lucas Cavendish.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Dear, Peter. 2007. “A Philosophical Duchess: Understanding Margaret Cavendish and the Royal Society.” In Science, Literature, and Rhetoric in Early Modern England, edited by Juliet Cummins and David Burchell. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

Detlefsen, Karen. 2006. “Atomism, Monism, and Causation in the Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish.” Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy 3: 199-240.

______. 2007. “Reason and Freedom: Margaret Cavendish on the Order and Disorder of Nature.” Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 89 (2): 157-191.

______. 2009. “Margaret Cavendish on the Relation between God and World.” Philosophy Compass4 (3): 421-438.

______. 2012. “Margaret Cavendish and Thomas Hobbes on Freedom, Education, and Women.” In Feminist Interpretations of Thomas Hobbes, edited by Nancy J. Hirschmann and Joanne H. Wright. College Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Duncan, Stewart. 2012. “Debating Materialism: Cavendish, Hobbes, and More.” History of Philosophy Quarterly 29 (4): 391-409.

Fitzmaurice, Susan. 2003. “Margaret Cavendish, the Doctors of Physick and Advice to the Sick.” In A Princely Brave Woman: Essays on Margaret Cavendish, edited by Stephen Clucas. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Green, Karen, and Jacqueline Broad. 2006. “Fictions of a Feminine Philosophical Persona: Christine de Pizan, Margaret Cavendish and Philosophia Lost.” In The Philosopher in Early Modern Europe: the Nature of a Contested Identity, edited by Conal Condren, Stephen Gaukroger and Ian Hunter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, Frances. 1997. “Living in the Neighbourhood of Science: Mary Evelyn, Margaret Cavendish and the Greshamites.” In Women, Science and Medicine: 1500-1700. Mothers and Sisters of the Royal Society, edited by Lynette Hunter and Sarah Hutton. Stroud: Alan Sutton.

Hutton, Sarah. 1997. “Anne Conway, Margaret Cavendish and Seventeenth Century-Scientific Thought.” In Women, Science and Medicine 1500-1700, edited by Lynette Hunter and Sarah Hutton.

______. 1997. “In dialogue with Thomas Hobbes: Margaret Cavendish’s natural philosophy.” Women’s Writing 4 (3): 421-432.

______. 2003. “Margaret Cavendish and Henry More.” In A Princely Brave Woman: Essays on Margaret Cavendish, edited by Stephen Clucas. Aldershot: Ashgate.

______. 2004. “John Finch, Thomas Hobbes and Margaret Cavendish.” In Anne Conway: a Woman Philosopher, edited by Sarah Hutton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

______. 2009. “In Dialogue with Thomas Hobbes: Margaret Cavendish’s Natural Philosophy.” In Margaret Cavendish, edited by Sara H. Mendelson. Farnham: Ashgate.

James, Susan. 1999. “The Philosophical Innovations of Margaret Cavendish.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 7 (2): 219-244.

______. 2003. “Introduction.” In Margaret Cavendish: Political Writings, edited by Susan James. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

______. 2009. “The Philosophical Innovations of Margaret Cavendish.” In Margaret Cavendish, edited by Sara H. Mendelson. Farnham: Ashgate.

Kargon, Robert Hugh. 1966. Atomism in England from Hariot to Newton. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Keller, Eve. 1997. “Producing Petty Gods: Margaret Cavendish’s Critique of Experimental Science.” ELH 64 (2): 447-471.

Lewis, Eric. 2001. “The Legacy of Margaret Cavendish.” Perspectives on Science: Historical, Philosophical, Social 9 (3): 341-365.

Linden, Stanton J. 2001. “Margaret Cavendish and Robert Hooke: Optics and Scientific Fantasy in The Blazing World.” In Esotérisme, Gnoses & Imaginaire Symbolique: Mélanges Offerts à Antoine Faivre, edited by Richard Caron, Joscelyn Godwin, Wouter J. Hanegraaff and Jean-Louis Vieillard-Baron. Louvain: Peeters.

Lynch, Marianne. 2008. “A Perfect Stranger: The Development of Margaret Cavendish’s Natural Philosophy.” PhD Dissertation, Concordia University, Canada.

Malcolmson, Cristina. 2013. Studies of Skin Color in the Early Royal Society: Boyle, Cavendish, Swift, Literary and Scientific Cultures of Early Modernity. Burlington: Ashgate.

Mendelson, Sara Heller, ed. 2009. Margaret Cavendish. Surrey: Ashgate.

Merchant, Carolyn. 1989. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. New York: Harper & Row.

Merrens, Rebecca. 1996. “A Nature of ‘Infinite Sense and Reason’: Margaret Cavendish’s Natural Philosophy and the ‘Noise’ of a Feminized Nature.” Women’s Studies 25 (5): 421-38.

Michaelian, Kourken. 2009. “Margaret Cavendish’s Epistemology.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 17 (1): 31-53.

Mintz, Samuel. 1952. “The Duchess of Newcastle’s Visit to the Royal Society.” The Journal of English and German Philology 51: 168-76.

Monroy-Nasr, Zuraya. 2003. “Epistemología y Sujeto en la Filosofía Antimecanicista de Margaret Cavendish.” Revista Latinoamericana de Filosofia 29 (2): 185-198.

Nelson, Holly Faith, and Sharon Alker. 2014. “‘Perfect according to Their Kind’: Deformity, Defect, and Disease in the Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish.” In The Idea of Disability in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Chris Mounsey. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press.

O’Neill, Eileen. 2001. “Introduction.” In Margaret Cavendish: Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, edited by Eileen O’Neill. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2001).

______. 2013. “Margaret Cavendish, Stoic Antecedent Causes, and Early Modern Occasional Causes.” Revue Philosophique de la France et de l’Etranger 138 (3): 311-326.

Parageau, Sandrine. 2008. “The Function of Analogy in the Scientific Theories of Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673) and Anne Conway (1631-1679).” Etudes Epistémè 14: 89-104.

______. 2010. “Catching the ‘Genius of the Age’: Margaret Cavendish, Historian and Witness.” Etudes Epistémè 17: 55-67.

Parageau, Sandrine, and Line Cottegnies. 2008. “La Contribution des Femmes au Débat Philosophique en Angleterre au Milieu du XVIIe Siècle Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673), Anne Conway (1631-1679), et la Philosophie de la Nature.” PhD Dissertation, Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle (Paris).

Rees, Emma L. E. 2003. Margaret Cavendish: Gender, Genre, Exile. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

______. 2004. “Margaret Cavendish: Gender, Genre, Exile.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 12 (4): 731-741.

Robinson, Leni. 2009. “A Figurative Matter: Continuities Between Margaret Cavendish’s Theory of Discourse and her Natural Philosophy.” PhD Dissertation, University of British Columbia, Canada.

Rogers, John. 1996. The Matter of Revolution: Science, Poetry, and Politics in the Age of Milton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Rudan, Paola. 2011. “Il Centro Eccentrico: Le Donne, il Femminismo e il Soggetto a Sesso Unico.” Filosofia Politica 25 (3): 365-383.

Sarasohn, Lisa T. 1984. “A Science Turned Upside Down: Feminism and the Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish.” Huntington Library Quarterly: A Journal for the History and Interpretation of English and American Civilization 47 (4): 289-307.

______.1999. “Margaret Cavendish and Patronage.” Endeavour 23 (3): 130-32.

______. 1999. “Thomas Hobbes and the Duke of Newcastle: A Study in the Mutuality of Patronage before the Establishment of the Royal Society.” Isis 90 (4): 715-737.

______. 2003. “Leviathan and the Lady: Cavendish’s Critique of Hobbes in the Philosophical Letters.” In Authorial Conquests: Essays on Genre in the Writings of Margaret Cavendish, edited by Line Cottegnies and Nancy Weitz. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; Associated University Presses.

______.2009. “A Science Turned Upside Down: Feminism and the Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish.” In Margaret Cavendish, edited by Sara H. Mendelson. Farnham, England: Ashgate.

______. 2010. The Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish: Reason and Fancy During the Scientific Revolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

______. 2011. “Margaret Cavendish, William Newcastle, and Political Marginalization.” English Studies 92 (7): 806-817.

Sarasohn, Lisa T., and Brandie R. Siegfried, eds. 2014. God and Nature in the Thought of Margaret Cavendish. Farnham: Ashgate.

Schiebinger, Londa. 1991. “Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle.” In Modern Women philosophers, 1600-1900, Vol. 3, edited by Mary Ellen Waithe. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Semler, L. E. 2012. “Margaret Cavendish’s Early Engagement with Descartes and Hobbes: Philosophical Revisitation and Poetic Selection.” Intellectual History Review 22 (3): 327-353.

Sheehan, Richard Johnson, and Denise Tillery. 2001. “Margaret Cavendish, Natural Philosopher: Negotiating Between the Metaphors of the Old and New Sciences.” Eighteenth Century Women 1: 1-18.

Siegfried, Brandie R. 2003. “Anecdotal and Cabalistic Forms in Observations upon Experimental Philosophy.” In Authorial Conquests: Essays on Genre in the Writings of Margaret Cavendish, edited by Line Cottegnies and Nancy Weitz. Madison, NJ; London: Fairleigh Dickinson UP; Associated UP.

Smith, Hilda L. 2005. “The Many Representations of the Marquise Du Chatelet.” In Men, Women, and the Birthing of Modern Science, edited by Judith P Zinsser. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

______. 2005. “Margaret Cavendish and the Microscope as Play.” In Men, Women, and the Birthing of Modern Science, edited by Judith P Zinsser, pp. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

______. 2007. “Margaret Cavendish and the False Universal.” In Virtue, Liberty, and Toleration: Political Ideas of European women, 1400-1800, edited by Jacqueline Broad and Karen Green. Dordrecht: Springer.

Stevenson, Jay. 1996. “The Mechanist-Vitalist Soul of Margaret Cavendish.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 36 (3): 527-543.

Strauss, Elisabeth Wilhelmine. 1993. “Organismus versus Maschine: Margaret Cavendish Kritik am Mechanistischen Naturmodell.” In Das Sichtbare Denken, Modelle and Modellhaftigkeit in der Philosophie un den Wissenschaften, edited by Jorge Mass. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

______. 1997. “Die Naturphilosophie von Margaret Cavendish (1623 – 1673) im Umfeld von Thomas Hobbes, Henry More und den Empiristen der Royal Society.” PhD dissertation, Frei Universiteit, Berlin, Germany.

______. 1999. Die Arithmetik der Leidenschaften: Margaret Cavendish’s Naturphilosophie. Stuttgart: Metzler-Verlag.

Tillery, Denise. 2003. “Margaret Cavendish as Natural Philosopher: Gender and Early Modern Science.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 28: 200–08.

______. 2007. “‘English Them in the Easiest Manner You Can’: Margaret Cavendish on the Discourse and Practice of Natural Philosophy.” Rhetoric Review 26 (3): 268-285.

Wallraven, Miriam. 2004. “‘My Spirits Long to Wander in the Air … ‘: Spirits and Souls in Margaret Cavendish’s Fiction between Early Modern Philosophy and Cyber Theory.” Early Modern Literary Studies: A Journal of Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century English Literature 14.

Wallwork, Jo. 2001. “Old Worlds and New: Margaret Cavendish’s Response to Robert Hooke’s Micrographia.” In Women Writing, 1550-1750, edited by Jo Wallwork and Paul Salzman. Bundoora, Australia: Meridian.

Walters, Lisa. 2014. Margaret Cavendish: Gender, Science and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Webster, Erin. 2011. “Margaret Cavendish’s Socio-Political Interventions into Descartes’ Philosophy.” English Studies 92 (7): 711-728.

Weise, Wendy S. 2012. “Recent Studies in Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (2001-2010).” English Literary Renaissance 42 (1): 146-176.

Weststeijn, Thijs. 2008. Margaret Cavendish in de Nederlanden: Filosofie en schilderkunst in de Gouden Eeuw. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Wilson, Catherine. 2007. “Two Opponents of Material Atomism: Cavendish and Leibniz.” In Leibniz and the English-Speaking World, edited by P. Phemister and Stuart Brown. Dordrecht: Springer.

Wolfe, Charles. 2013. “Vitalism and the Resistance to Experimentation on Life in the Eighteenth Century.” Journal of the History of Biology 46 (2): 255-282.

Selected secondary sources in Political Philosophy

Boyle, Deborah. 2006. “Fame, Virtue, and Government: Margaret Cavendish on Ethics and Politics.” Journal of the History of Ideas 67 (2): 251-289.

Broad, Jacqueline, and Karen Green, eds. 2007. Virtue, Liberty, and Toleration: Political Ideas of European Women, 1400-1800. Dordrecht: Springer.

______, eds. 2009. A History of Women’s Political Thought in Europe, 1400-1700 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Detlefsen, Karen. 2012. “Margaret Cavendish and Thomas Hobbes on Freedom, Education, and Women.” In Feminist Interpretations of Thomas Hobbes, edited by Nancy J. Hirschmann and Joanne H. Wright. College Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Iyengar, Sujata. 2002. “Royalist, Romancist, Racialist: Rank, Gender, and Race in the Science and Fiction of Margaret Cavendish.” ELH 69 (3): 649-672.

James, Susan. 2003. “Introduction.” In Margaret Cavendish: Political Writings, edited by Susan James. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

______, ed. 2003. Margaret Cavendish: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rogers, John. 1996. The Matter of Revolution: Science, Poetry, and Politics in the Age of Milton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Rudan, Paola. 2011. “Il Centro Eccentrico: Le donne, il Femminismo e il Soggetto a Sesso Unico.” Filosofia Politica 25 (3): 365-383.

Webster, Erin. 2011. “Margaret Cavendish’s Socio-Political Interventions into Descartes’ Philosophy.” English Studies: A Journal of English Language and Literature 92 (7): 711-728.

Selected biographical studies

Ballard, George. 1775. Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain: Who Have Been Celebrated for their Writings or Skill in the Learned Languages, Arts, and Sciences . London: Printed for T. Evans, in the Strand, Near York-Buildings.

Ballard, George, and Ruth Perry, eds. 1985. Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain: Who Have Been Celebrated for their Writings or Skill in the Learned Languages, Arts, and Sciences. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Bartow, Virginia. 1957. “Philosophical Studies of the Duchess of Newcastle.” Journal of Chemical Education 34 (2): 82-87.

Beneden, Ben van, and Nora de Poorter, eds. 2006. Royalist Refugees: William and Margaret Cavendish in the Rubens House, 1648-1660 . Antwerp: Rubenshuis & Rubenianum.

Grant, Douglas. 1957. Margaret the First: Biography of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, 1623-1673. London: Hart-Davis.

Jones, Kathleen. 1988. A Glorious Fame: the Life of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623-1673). London: Bloomsbury.

Mendelson, Sara Heller. 1987. The Mental World of Stuart Women: Three Studies. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

De Longueville, Thomas. 1910. The First Duke and Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. By the Author of “A Life of Sir Kenelm Digby” [i.e. Thomas Longueville] … With illustrations. London: Longmans & Co.

Perry, Henry Ten Eyck. 1918. The First Duchess of Newcastle and her Husband as Figures in Literary History. Boston and London: Ginn and Company.

Trease, Geoffrey. 1979. Portrait of a Cavalier: William Cavendish, First Duke of Newcastle. New York: Taplinger.

Whitaker, Katie. 2002. Mad Madge: the Extraordinary Life of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, the First Woman to Live by her Pen. New York: Basic Books.

Woolf, Virginia. 1925. “The Duchess of Newcastle.” In The Common Reader, edited by Virginia Woolf. London: L. & V. Woolf at the Hogarth Press.

4. Philosophy & Teaching

This section is forthcoming. Our team is working with the Advisory Board on materials interpreting Cavendish’s philosophical work and accompanying teaching materials. In the meantime, please see the Teaching section of the website for sample syllabi.

Videos

Project Vox has partnered with the Wireless Philosophy project to create educational videos on various topics related to the women philosophers. Please subscribe to our newsletter to stay on top of new video resources.

5. Correspondence

Please note that just as there is no authoritative edition of Cavendish’s work, there is no comprehensive edition of her extant correspondence. More research on her correspondence and extant manuscripts is forthcoming. Below is information on some of the frequently cited sources of Cavendish’s correspondence.

Philosophical correspondence

Cavendish was able to engage only a few philosophers in more extensive correspondence. The two key extant exchanges are with Constantijn Huygens and Joseph Glanvill, and are covered in detail in Sections 5.1 and 5.2. The correspondence with Huygens covers (1653-1671) and discusses the phenomenon of Rupert’s Drops and Cavendish’s presentation of her works to the University of Leiden. The correspondence with John Glanvill (probably 1667-1668) discusses topics such as pre-existence of the souls, Platonist views on substance, and the existence of witches.

A Collection of Letters and Poems

A key source of correspondence is the collection of poems and letters sent to Cavendish and her husband William, which William published in 1678 after her death: A Collection of Letters and Poems Microform / Written by Several Persons of Honour and Learning, upon Divers Important Subjects, to the late Duke and Dutchess of Newcastle. It also includes a number of eulogies dedicated to Cavendish. The collection is from a variety of authors, poets such as Thomas Shadwell, academics from Cambridge University, and natural philosophers such as Walter Charleton, Kenelm Digby, Thomas Hobbes, Constantijn Huygens, Joseph Glanville, and Henry More. Cavendish knew most of these philosophers through her husband and his brother Charles Cavendish, who actively promoted the new experimental philosophy and sponsored philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes (see Section 6 on Connections.)

Many of these letters are polite thank you letters full of praise for Cavendish’s presents of her works. Cavendish was in the habit of sending expensively printed copies of her own books to eminent scholars and university libraries, including Oxford, Cambridge and Leiden, in order to gain public recognition. Cavendish’s high social position and the support of her politically, academically, as well as financially well-connected husband William enabled her to do so. The lucky recipients were thus obliged by social convention, and sometimes by the need for patronage, to accept and praise the presents. Cavendish’s approach was scandalous at a time when women were expected to stay out of public limelight, or at the very least to publish their thoughts anonymously. This was the path taken by Conway and Masham, but Cavendish preferred to be ridiculed by society rather than stay silent. There is scholarly debate, however, as to whether her strategy worked: there is general agreement that she was not taken seriously by her contemporaries, but it is not clear whether this was because of the quality of her philosophical ideas, the non-conventional genres she used to express them, or because of her blatant disregard for social conventions.

Primary source

Cavendish, William, Duke of Newcastle, ed. 1678. A Collection of Letters and Poems Microform / Written by Several Persons of Honour and Learning, upon Divers Important Subjects, to the late Duke and Dutchess of Newcastle. London: Printed by Langly Curtis in Goat Yard on Ludgate Hill.

A spreadsheet overview of the Letters and Poems is available for download below. Please note that there are two worksheets; one with all the letters and one with only the letters from philosophers.

Courtship letters and poems

Another source of correspondence are the courtship poems and letters that William and Margaret Lucas wrote to each other in 1645. The letters are only available in the 1956 edition by Douglas Grant. The poems are available in the English Poetry (proprietary) online database. (Information on manuscripts is forthcoming.)

Letter to John Evelyn

There is also an extant letter from Cavendish to John Evelyn (1620-1706), writer, diarist, botanist, and one of the founding members of the Royal Society. The letter is reprinted in the Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn (1857) edited by William Bray. In the letter Cavendish thanks Evelyn for sending her his work Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber in his Majesty’s Dominions (1664). Evelyn originally presented his work as a paper at the Royal Society in 1662. It became one of the most influential works on the topic of forestry. The letter is available via Hathi Trust and for download below.

Digital copy of letter: PDF file

Hathi Trust link

Reprints of primary sources

Bray, Willliam, ed. 1857. Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, Vol. 3. London: Henry Colburn. (See pg. 226)

Grant, Douglas, ed. 1956. The Phanseys of William Cavendish, Marquis of Newcastle, Addressed to Margaret Lucas. London: Nonsuch.

Secondary sources

Chambers, Douglas D.C. 2004-15. “Evelyn, John (1620–1706).” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition, Jan 2008), edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Link.

Hunter, Michael. 2004-15. “Founder members of the Royal Society (act. 1660–1663).” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition), edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Link.

Fitzmaurice, James. 2004. The Intellectual and Literary Courtship of Margaret Cavendish. Early Modern Literary Studies Special Issue 14. Link.

For image sources and permissions please see our image gallery.

5.1 Correspondence with Constantijn Huygens