Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

“But who has prohibited women private and individual studies? Do they not have a rational soul like men? … What divine revelation, what determination of the Church, what dictate of reason made for us such a severe law?” —Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, in Autodefensa Espiritual (translated from Tapia Mendez 1993).

Born at the end of the Spanish “Golden Century,” Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz is, in many senses, the perfect embodiment of the Baroque spirit. Both her life and her writings are marked by a series of tensions and contrasts. Although it may have been possible for Sor Juana’s choices and life circumstances to destine her for a life of opprobrium and relative obscurity, given her birth out of wedlock, her oppressive and hierarchical colonial context, and her membership in a religious order, she ultimately became one of the most famous polymaths of the 17th century. For most of her life, she maintained close friendships with many members of the political and cultural elite of New Spain, and she achieved a series of literary and intellectual feats that led one of her admirers to describe her as “Madre que haces chiquitos a los más grandes” (“a Mother who makes the greatest so small”). Just as her personal and social life was marked by tensions between her marginal status as a nun and the central role she played in the cultural and intellectual life of New Spain under the patronage of two successive Vicereines, her writings are often marked by tensions and contrasts between competing aspirations. Indeed, while Sor Juana defends in some pieces her right to study and be educated, she demurs in others from certain intellectual pursuits, writing “También es vicio el saber” (“Knowledge is also a vice”). Praised and celebrated by many as “the Phoenix of Mexico” during her lifetime, she was nonetheless forced to recant her works at the end of her life.

In spite of all these tensions and contrasts, Sor Juana’s life and writings have continuously fascinated many people, both in her homeland and beyond. Her poetry and her plays have been the object of dozens of scholarly studies and monographs, all of which recognize her immense literary talent and her amazing poetic abilities. However, one aspect of Sor Juana’s polymathy that has received comparatively little attention is her engagement with philosophical questions. Though her philosophical work is not presented in conventional forms such as treatises or dialogues, some of her poetry (in particular, the epistemological poem First Dream, which is considered her masterpiece) and her letters (the Letter Worthy of Athena and the Reply to Sor Filotea) offer novel suggestions regarding the relationship between dreams and knowledge, the connection between the natural and the divine, and original arguments supporting the right of women to study and be educated. In addition to these intellectual accomplishments, Sor Juana displayed an interest in the indigenous groups of New Spain by composing a few pieces in Nahuatl and by offering a limited defense of indigenous cultures and religions in her Loa (prologue) to Divine Narcissus. She presented her thoughts on the duties of heads of state to their subjects in Allegorical Neptune, just as Bartolomé de las Casas had a century before her. In light of all this, Sor Juana stands not only as the first woman to have written substantial philosophical works on the American continent, but also as one of the first female indigenistas, thus paving the way for later figures such as noted Mexican novelist and essayist Rosario Castellanos.

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana was born on November 12 in either the year 1648 or 1651. In her early life, she also went by the shorter name Juana Ramírez de Asbaje. She adopted the more famous version of her name—Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz—after joining the Hieronymite order of nuns. She was born out of wedlock in the village of San Miguel Nepantla, 60 km southeast of Mexico City. She was the illegitimate child of Isabel Ramírez Santillana, a criolla woman (a person of white European Spanish descent born in the Americas), and Pedro Manuel de Asbaje y Vargas Machuca, a Spanish captain who left her life very early on, and about whom she knew very little. Understanding the societal role imposed upon her as a criolla and an illegitimate daughter—both of which were conditions that would have left others with no prospects in life—make her subsequent renown in court, intellectual history, and popular culture even more remarkable.

Although not much is known about her early life, it is clear that her maternal grandfather, Don Pedro Ramírez de Santillana, was an influential figure in her intellectual development. His extensive library captivated the precocious child prodigy, who later in life would say that at three years old, she was “inflamed with a desire to know how to read,” a skill which she soon accomplished. Her appetite for knowledge must have quickly shown her the benefits of a university education. During her lifetime, only males were allowed that privilege, however, and graduation from a university was a prerequisite for becoming a respected teacher. She begged her mother to dress her up in boys’ clothes so that she could attend such an institution in Mexico. “I began to plague my mother with insistent and importunate pleas: she should dress me in boy’s clothing and send me to Mexico City to live with relatives, to study and be tutored at the University” (Reply to Sor Filotea). Needless to say, she was scolded and never achieved this goal.

Sor Juana was apparently distressed by her lack of formal education. She complained about the unfortunate conditions of her early auto-didacticism in her later writings, “Study and more study, with no teachers but my books. Thus I learned how difficult it is to study those soulless letters, lacking a human voice or the explication of a teacher.” She added, “I undertook this great task without benefit of teacher, or fellow students with whom to confer and discuss, having for a master no other than a mute book, and for a colleague, an insentient inkwell” (Reply to Sor Filotea).

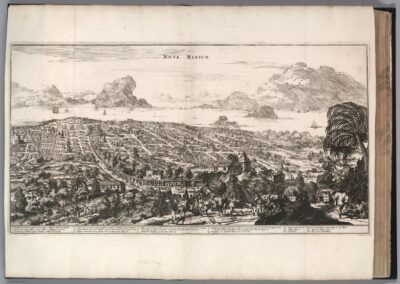

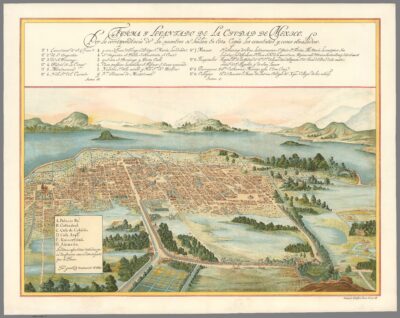

In 1656, she was sent to Mexico City by her mother to live with her maternal aunt and uncle, María Ramírez Santillana and Juan de Mata. Mexico City had around 50,000 inhabitants at the time and was the bustling heart of New Spain’s colonial life. She began her study of Latin in 1659 under the tutelage of Bachelor Martín de Olivas—it is said that she learned the language in only twenty lessons. If this is true, it is an early manifestation of the literary and linguistic genius that she demonstrated in her later work. In order to give herself motivation to study seriously, she would punish her own laziness or ineptitude by cutting her hair.

In 1664, she entered the court of Antonio Sebastián Álvarez de Toledo, 2nd Marquess of Mancera, as a lady-in-waiting for his wife, the Vicereine Leonor Carreto. The Viceroyals of New Spain were described as the “living images” of the monarchs in Spain, and therefore had some autonomy in the colonial government structure of the Viceroyal system, which stood in for imperial bureaucracy. They expressed love and loyalty for the monarch, and cooperated with them on important matters, so a position in the court of Leonor Carreto as a lady-in-waiting was an exceedingly impressive accomplishment for Juana Inés. The court was based on a household model, with blurred distinctions between the household and the bureaucratic figures. The patron and client relationships in this model were based on ties of loyalty and social networks, so Juana Inés benefitted from the prestige of being in the Vicereine’s household, especially since she managed to entertain the court with her witty command of language, poetry, and works of theatre.

She made her first attempt at religious life in August 1667, when she entered the Convent of San José de las Carmelitas de México. However, she renounced the Carmelites on November 18 of that year, largely due to their rigidity.

Upon returning to court, she underwent an examination by 40 scholarly men from the University of Mexico including philosophers, theologians, mathematicians, historians, poets, and humanists. This examination was arranged by the Viceroy to assess her intellect, after she had impressed the Viceroyal court; ultimately the men were astounded by her multi-disciplinary knowledge.

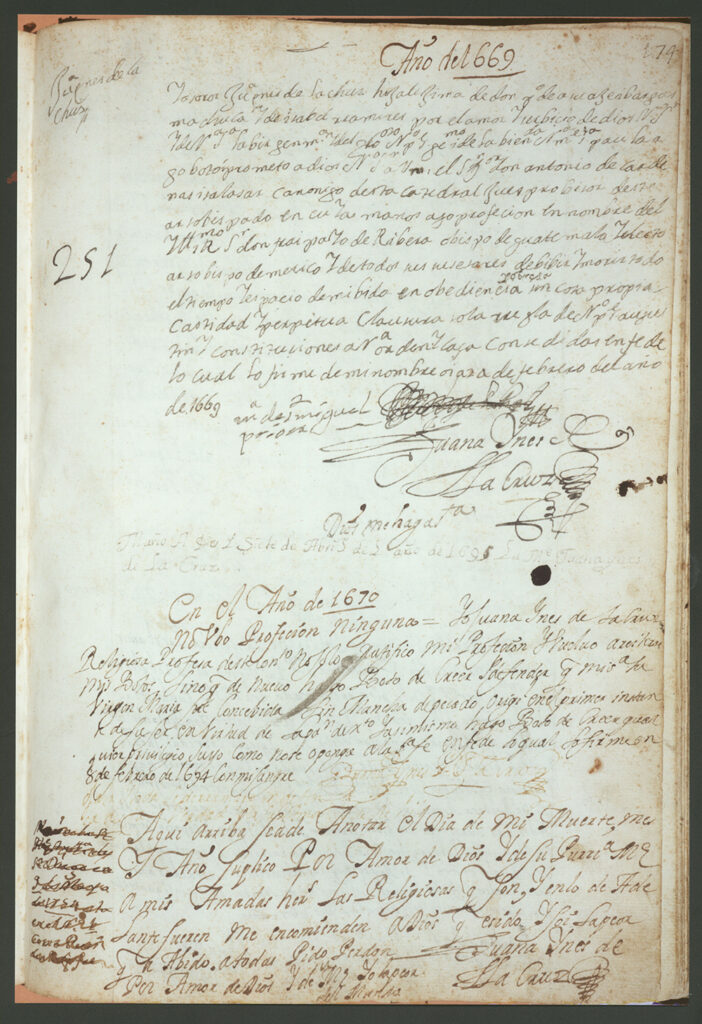

With no desire to marry, but rather searching for the autonomy necessary to study, she once again entered religious life, this time at the Convent of San Jerónimo in February 15, 1669. Here she would stay for the rest of her life, composing her life’s work in poetry, drama, and prose. The convent was one of the only places for women to pursue intellectual activity during her time, though the environment was not perfectly conducive to that pursuit, as can be seen from a controversy marking the end of her life. In her La Respuesta, she explained her motivation as animated by antipathy for marriage, despite the knowledge that convent life was going to entail “conditions most repugnant to my nature.” At this point, she transitioned from one distinct period of her life to another, from courtly life to religious life. However, she did continue to keep close connections with the court. For example, she frequently had visits from court members and friends such as Don Carlos Sigüenza y Góngora in the locutorio (a kind of parlor) of the convent, where they engaged in intellectual discussions called tertulias. The subjects ranged from secular to religious.

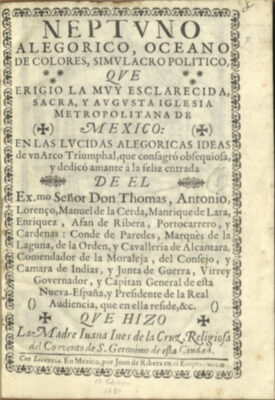

Her connection to court was further strengthened by her writing Allegorical Neptune, a long Baroque prose piece accompanied by explanatory poetic verses which was designed to decorate a triumphal arch in celebration of the incoming Viceroy of New Spain, Tomás de la Cerda y Aragón, Marquess of Laguna, and his wife María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga. In it, she compares the virtues of the new Viceroy to those of the god Neptune, and establishes a link between ancient Egypt, Christianity, and New Spain. This work was so well-received that scholars consider this to have established Sor Juana’s long friendship with the new Viceroyals, who also became her patrons as the last ones had.

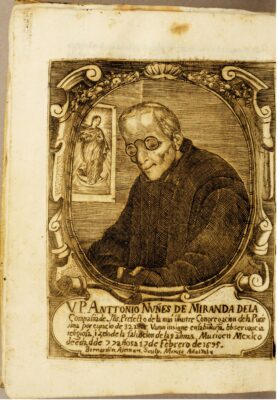

As detailed in her Letter from Monterrey, or Spiritual Self-Defense (Carta de Monterrey, or Autodefensa Espiritual) in 1681, this patronage also enabled her to eventually fire her confessor, Antonio Núñez de Miranda, who was jealous of her success and fame as his own declined.

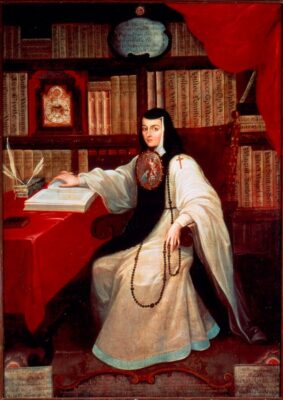

In addition to writing, she also worked as the accountant of the convent, and as a music teacher to the nearby girls’ school (by some accounts). There is a book of cooking recipes that was used by the convent, which may have been written by Sor Juana. She may also have written a small treatise on logic, and another on music theory, both of which are lost. In her personal nun’s cell, she was said to have a maid and 400–4000 volumes, along with scientific equipment such as a telescope, although portraits of her have tended to emphasize only her collection of literature. Some scholars describe her as the first bibliophile of the New World.

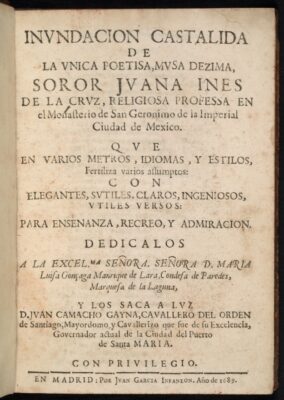

Throughout her life, she wrote over 200 works, often in groups of poems and villancicos, or carols, and in nearly all literary genres. Many were written for special occasions such as funerals, feasts, and birthdays. Two volumes of her poetry were published in Spain during her lifetime, and one shortly after. She also had a work entitled Castalidan Flood, of the Unique poet, the Tenth Muse of Mexico, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, published with the help of the Countess of Paredes.

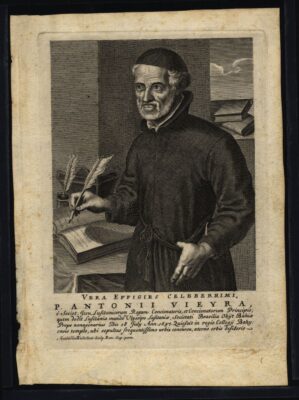

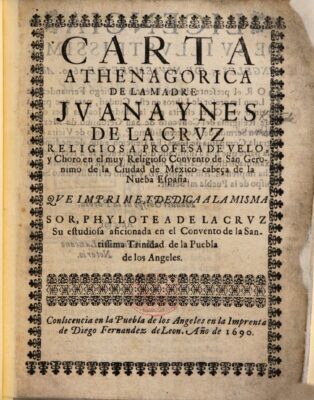

In November 1690, a private letter from her to an acquaintance, later named Letter Worthy of Athena, or Critique of a Sermon, was published without her consent by the Bishop of Puebla. In her epistolary essay, she criticized a sermon given by Jesuit priest António Vieyra on Christ’s love. Vieyra claimed that the Church fathers St. John Chrysostom, St. Thomas Aquinas, and St. Augustine of Hippo did not understand the meaning of Christ’s demonstrations or proofs of his love, including the question of which among them was the greatest. Sor Juana takes up a defense of these three Church fathers and offers her own interpretation of the significance of Christ’s sacrifice and God’s demonstrations of love.

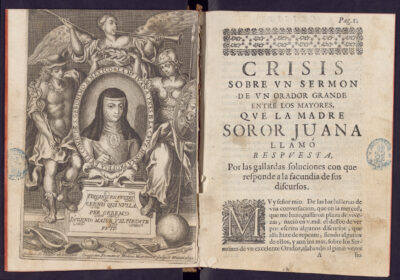

The Bishop of Puebla published the content of the letter along with his own response to her arguments under the pseudonym of Sor Filotea de la Cruz (i.e. Lover of God), impersonating a nun and chastising Sor Juana for not writing more on theology and for spending too much time on poetry and the profane sciences. The letter was respectful but threatening, insofar as it indirectly attacked her character and enjoined her to be more like other nuns of good repute. Although Sor Juana wrote a lengthy and substantial response to this attack, she did not publish it during her lifetime. The Response to the most Illustrious Poetess Sor Filotea de la Cruz was written on March 1, 1691, but published posthumously in 1700 in a volume titled Fame and Posthumous Works. In this magnificent epistolary essay, she mounted a defense of women’s right to study and teach. It is clear throughout this response that she believed religious devotion and intellectual freedom could go hand in hand, and that a woman need not forsake righteousness in order to study. The autobiographical details included in this essay have long attracted the fascination of scholars, and remain a central source for all biographies of Sor Juana’s life.

After the publication of these epistolary essays, Sor Juana turned towards more religious duties and withdrew from her public persona as an intellectual. Some scholars, including Irving Leonard and Octavio Paz, hold that powerful men in the church like Nuñez de Miranda and Aguiar y Seijas forced her to renounce her intellectual career and renew her vows as a “bride of Christ”. Indeed, there are documents showing her agreement to undergo penance for her previous work, including one which, in 1694, she famously signed “Yo, la Peor de Todas” (“I, the worst of all women”) in her own blood.

Sor Juana died on April 17, 1695 while treating a sick friend who was struck by a plague in the convent. Her body is supposedly buried in the Convent of Santa Paula of the “Hieronymite Order” of Saint Jerome. Although much of her work is lost to time, and her books and instruments were either given to charity or seized by officials, we cannot be certain that she stopped writing during the years leading up to her death.

An unfinished poem was found in Sor Juana’s cell after her death. It was addressed to her supporters in Spain, thanking them for “breathing another spirit into [her],” that is, giving her work new life by representing her not as she was — a nun struggling (as she put it) to “learn more [and] be ignorant about less” — but as they wanted to imagine her, a great intellectual, a sublime poet, a phoenix rising from the ashes.

1.1 Modern Reception

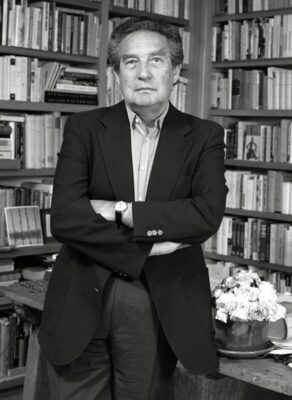

Sor Juana de la Cruz is one of those rare philosophical figures who not only left a tremendously influential and thought-provoking legacy for posterity, but also features prominently in the popular culture of an entire people. Her numerous “afterlives” have morphed with the sentiments of the times. While she took part enthusiastically in the intellectual conversations of her contemporaries, especially within the court of Viceregal New Spain and the circle of the Spanish literati, her ideas and name received little notice during the vast majority of the 18th and 19th centuries. However, her work has recently experienced a resurgence in the modern Mexican imagination, mainly due to her “re-discovery” by the renowned Mexican author Octavio Paz.

In 1982, Paz published a detailed biography on her work that skyrocketed her visibility both among scholars and the general public. In Sor Juana: Or, the Traps of Faith, he investigated what he saw as the great contradictions and mysteries of her life, including her ability to rise to fame from the unfortunate circumstances of her birth, her choice to go from glittering court erudite to cloistered nun, and her striking renunciation of books and secular learning. His contemporary esteem renewed interest in this symbolic figure, which has only grown in recent years. Prior to Paz’s seminal publication, the Complete Works of Sor Juana compiled by scholar Antonio Mendez Plancarte was the most notable work about her life and achievements. While Plancarte considered her philosophy and literature with a critical and academic perspective, Paz familiarized readers with the figure through his enthusiasm and engrossing writing.

Sor Juana first appeared on the obverse of the Mexican banknote in 1978, with the brown 1,000 peso. Therefore, her image was well known prior to Paz’s biography. Her revived popularity subsequent to the publication inspired her continued presence on Mexican banknotes. She was honored in 1985 on the 2,000 peso banknote and again in 2007 on the new 200 peso bill issued by the Banco de Mexico, along with an excerpt from one of her most famous poems:

“Foolish men, who accuse,

Women without reason,

Without seeing that you create,

The very faults that you identify.”

Clearly, she is celebrated primarily as a feminist icon—a figure who spoke out against the restrictions on female education and who criticized gender power dynamics in society.

Of all the figures hitherto published on Project Vox, Sor Juana has unquestionably had the greatest modern impact. There are diverse representations of Sor Juana in historical novels, poetry, plays, films, musical performances, and the visual arts. With countless books written by those both within and outside academic circles, her image has been reframed, reinterpreted, and sensationalized in countless ways, making research into her personage all the more complex and compelling. A film from 1990 called “I, the Worst of All”, based on Paz’s biography, has a distinctly sexual tone, rather than an intellectual one: “Lesbian passion seething behind convent walls… Engrossing, Enriching, and Elegant!” The title refers to the fact that she signed in blood a renunciation of her intellectual pursuits with the provocative statement, “I, the Worst of All”. Although the romanticization and sexualization of her image as a lesbian nun no doubt stems from her affectionate poems addressed to both the first and second Vicereines in her life, as perhaps most blatantly depicted in the theatre production “Los Favores de Sor Juana,” there is no strong evidence that she engaged in romantic pursuits with either of these women, let alone demonstrated such overt sexuality as a cloistered nun. As far as we can tell, she chose to forgo a life of sexuality for the freedom to study, which was offered to her by the cloister.

On the other hand, it is possible that our skewed modern reception aligns with her desire to be viewed as more fantastical than she truly was. She elaborates on this sentiment in an unfinished poem that was found in her cell after her death in 1695—this piece also proves that she never truly gave up writing after her renunciation, and continued her intellectual work in private. The poem was addressed to her supporters in Spain, whom she thanked for “breathing another spirit into [her].” In other words, she expressed gratitude to those fans who crafted a new, more exciting life around her image, representing her name as something other than how she saw herself in reality: a nun struggling to “learn more [and] be ignorant about less.” They apparently raised her to an ideal of intellectual prowess, sublime poetic skill, and the mythological Phoenix of Mexico. Some striking words from this unfinished poem are, “You imagine me, and I exist.”

This self-refashioning reflects our modern representation of her in many ways, given her evidential command of languages and of important philosophical concepts. Nevertheless, there is no explicit mention by Sor Juana about the lesbian fantasies that have been attributed to her in our popular culture. Consequently, the situation remains unclear, as Paz himself mentions. Queer readings of Sor Juana’s love poetry to the Vicereines are plausible, though without more information it is difficult to gain clarity on the matter.

However, as societal values have become more inclusive, her pleas for educational rights—though admirable and historically influential—do not provide the shock value that they would have had in the 17th century. It is perhaps for this reason that our contemporary lens morphs her image to maintain that sense of fascination in this new age. Of course, there is no need to stretch the truth when telling her story as the sheer intensity of all her work and the conditions of her life—as an illegitimate daughter in a sexually oppressive and intellectually stifling time—which complicated her rise to fame as a contrarian provide us with more than enough material for fascination.

Her image has also been the focus of more interest in the Western world in recent years, especially due to her identity, which straddled religious orthodoxy and intellectual freedom, and her prescient efforts in multiculturalism are now constantly in our minds. She melded colonial and indigenous languages in her poetry, giving an unprecedented voice to Native American symbols and religious traditions in the Viceroyal court while stressing her own criolla identity.

For example, parts of Sor Juana’s “Villancico 224” were written in Nahuatl, while others were in Spanish. Switching between the two languages, she centered her narrative on both the Catholic Virgin of Guadalupe and Cihuacoatl, an indigenous goddess. We can see that she was not afraid to break boundaries between cultures, engaging in comparative religious explorations that equated the worth of Native American religions to that of Catholic saints—a striking decision given her life-long role as a Catholic nun during the time of the Inquisition. The dual focus of her work is such that it is often ambiguous whether she prioritized Catholic or indigenous religious figures, or whether she sought to harmonize the two. Scholars such as Nicole Gomez argue that her fusion of Spanish and Aztec religious traditions aimed to raise the status of indigenous religious traditions to equal that of Catholicism in New Spain as well as to chastise the egregious violence against native communities and traditions by New Spain.

Another example of her intercultural interests is seen in her Loa, or Prologue, to the Divine Narcissus. She centered this play on the interactions between two pairs of aptly named peoples from Indigenous and Spanish cultures, Occident and America, and Religion and Zeal, respectively. The work is informative in its description of Aztec rituals and gods, including Huitzilopochtli, who symbolized the land of Mexico. In their encounters, the two pairs of opposing peoples discuss their religious perspectives and come to the conclusion that their similarities are greater than their differences. Surely this was a noble attempt at religious harmony during the tumultuous and aggressive period of her life. In our contemporary age of religious extremism and hostility, we can undoubtedly admire and learn from her efforts to foster conversation between people of different backgrounds and bridge cultural divides by emphasizing similarities.

In Mexico, she is viewed as a more political figure in the sense that she is claimed by the nation as a visionary philosopher who belongs wholly to Mexico, unlike the typical thinkers who hailed from Spain during the Spanish Golden Age. Consequently, she has become a strong symbol of Mexican national pride, and has been promoted as such by the government.

Sor Juana’s name was inscribed in gold on the wall of honor in the Mexican Congress in April 1995. The town where Sor Juana grew up, San Miguel Nepantla in the municipality of Tepetlixpa, State of Mexico, was renamed in her honor as Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, and the walls of the town are adorned with her image. She is also known in the whole of Latin America as the “Tenth Muse” and the “first feminist of the Americas,” as well as the “Phoenix of Mexico.”

There are also connections drawn between Sor Juana and the more modern and popular artist Frida Kahlo. Scholar Theresa A. Yugar has focused her research with the question, “Why does the world know more about Frida Kahlo than Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz?” This comparison has since gained traction, and the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana honored both Frida Kahlo and Sor Juana on October 31, 2018 with a symbolic altar.

Sor Juana’s numerous complexities involving gender roles, racial identity, and religious harmony make her an especially modern thinker who fits well into the multicultural discourse of our day, and her influential life during the Golden Age makes her a proto-feminist from the New World. Therefore, if we want to understand more about our own age of ambiguity, globalization, and crossing boundaries, it would be beneficial to examine her novel approach to these issues, which, before most other people, she recognized as significant concerns for our collective humanity.

1.2 Chronology

| Date | Event |

| 12 November 1648 (or 1651) | Sor Juana is born as Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana in the village San Miguel Nepantla, though the exact date is still debated. In her early life also went by Juana Ramírez de Asbaje. Only in 1669, once she entered the convent, did she take her more well-known name: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. |

| 1656 | Sor Juana is sent to Mexico City to live with her maternal aunt and uncle: María Ramírez Santillana and Juan de Mata. |

| 1659 | Sor Juana begins studying Latin under the tutelage of Bachelor Martín de Olivas. She allegedly picked up the language in 20 lessons. |

| 1664 | Sor Juana joins the court of the Marquis and Marquise of Mancera in Mexico City. These Viceroyals were considered to be like “living images” of the monarch in Spain. |

| 1667 | Sor Juana enters the Convent of San José de las Carmelitas de México in August. On November 18 of the same year, she renounces her place for the convent’s rigid practices and style of worship. She then returns to the Viceroyals‘ court. |

| 1668 | The Marquis of Mancera gathers 40 male courtiers comprised of philosophers, theologians, mathematicians, historians, poets and other humanists to examine her intellect. She passes the thorough questioning and gains a prodigious reputation. |

| 1669 | Sor Juana enters the Convent of San Jerónimo in Mexico City on February 15 and remains there until her death. In committing to the convent, she severed ties with her official position at the Viceroyals’ court, though she retained a close and unofficial relationship with the remaining courtiers (i.e. Carlos Sigüenza y Góngora). |

| 1689 | Sor Juana composes two conjoined plays: the Divine Narcissus (Divino Narciso) and its Loa, or prologue. |

| 1690 | The Bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, publishes Sor Juana’s critique of a sermon by Jesuit priest António Vieyra, and does so without her consent. The published critique is named Letter Worthy of Athena (Carta Atenagórica). |

| 1691 | Sor Juana replies to the Bishop of Puebla with her Reply to Sor Filotea (Respuesta a sor Filotea de la Cruz). |

| 1692 | Sor Juana composes her poem First Dream (Primero Sueño). |

| 1694 | Antonio Nuñes de Miranda and Don Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas, religious leaders in Mexico City, lead a secret case against Sor Juana and sentence her to a renunciation of her intellectual career. The written renunciation is signed in her blood. |

| 1695 | Sor Juana dies on 15 April 1695. Her body is supposedly buried at the Convent of Santa Paula, of the Order of San Jerónimo. |

2. Primary Sources Guide

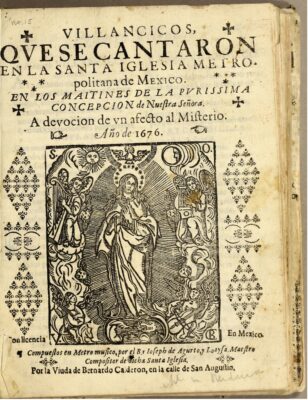

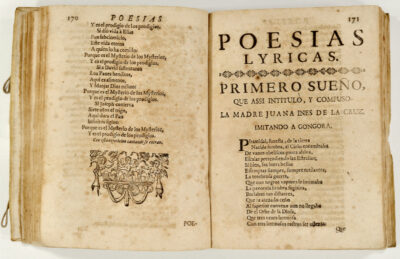

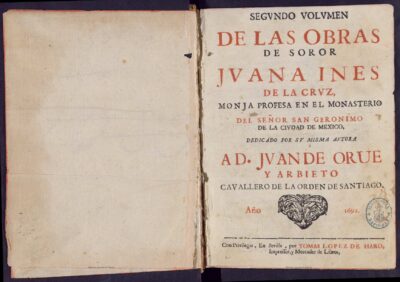

The publication of Sor Juana’s works was undertaken in two main periods. In the first, which roughly encompassed the last two decades of the 17th century, a selection of Sor Juana’s works was published in Spain. The first volume, which was published in Madrid by Juan García Infanzón under the title Inundación Castálida de la única poetisa (1689), included various sonnets, romances, décimas, loas, and the various poems and other texts that comprised the Neptuno Alegórico. This selection of works proved extremely popular in Spain. The Inundación Castálida was promptly followed by another volume titled Segundo tomo de las obras de sóror Juana Inés de la Cruz (1692), which was published in Seville by Tomás López de Haro. This volume contained various other poems previously unpublished (in particular sonnets, romances, endechas, and villancicos) as well as Primero Sueño, the Carta Atenegórica, and her two secular plays Los Empeños de una Casa and Amor es más laberinto.

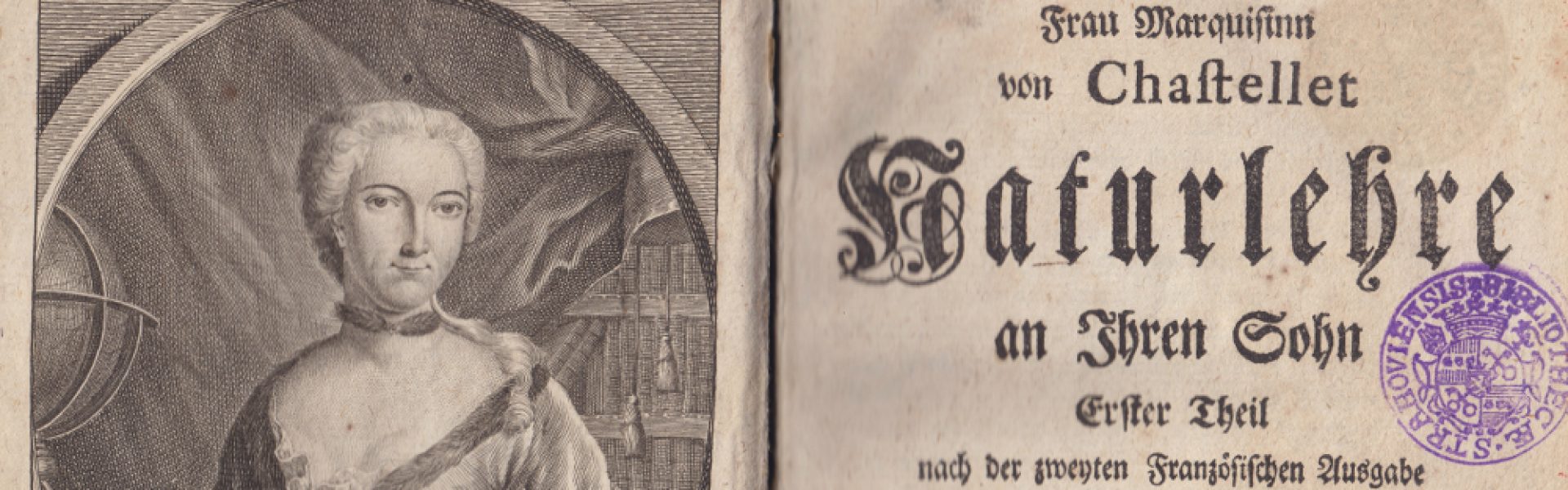

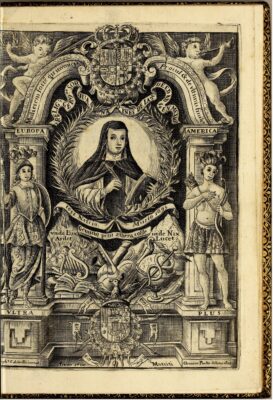

Subsequently, a few years after the death of Sor Juana, a third volume entitled Fama y obras póstumas del fénix de México (1700) was published in Madrid by Manuel Ruiz de Murga. This volume contains a series of poems that were written by various figures to honor and commemorate Sor Juana, as well as several pieces authored by Sor Juana that were not included in the two previously mentioned volumes. This volume contained the religious or devotional exercises as well as a series of other poems that had not been published previously, including the romance dedicated to her by the Count of La Granja and the romance that she penned in response. Fama y obras póstumas also features an elaborate frontispiece, engraved by Clemens Puche after a drawing by Joseph Caldevilla, that reflects the volume’s commemorative message. Composed of rich visual and textual symbolism, this frontispiece highlights Sor Juana as a cultural mediator between Spain and the New World.

At the center, we find a bust portrait of Sor Juana wearing the white tunic with a dark outer layer that was typically worn by Hieronymite nuns. Another reference to Saint Jerome is the banner above her that reads: “Mulierem fortē qis inveniet? / Procul & (et) de ultimis finibus?” This translates roughly to: “Who can find a strong or virtuous woman? / For her price [is] far above jewels.” It comes from the Vulgate, a version of the Bible translated into more everyday “vulgar” Latin by Saint Jerome in the late fourth century that became the standard version of the Old Testament used by the Catholic Church.

In her hands, Sor Juana holds a book and quill whose tip hovers as if we have just interrupted her writing something down. These attributes represent her legacy as a prominent scholar in Mexico. Indeed, Sor Juana was often referred to as the “Tenth Muse” by peers and admirers during her lifetime (Boyle 2016). The frontispiece visualizes her esteemed intellectual status in the form of an angel at the top right who plays a bugle or small trumpet, a common symbol of victory, triumph, and glory. Read as a fanfare trumpet and associated with military fanfare, this trumpet implies the fame and far-reaching impact of Sor Juana’s writings.

Below Sor Juana are multiple objects that further allude to her capacious humanist knowledge: the Staff of Hermes, a violin, a lute, a globe, and various books. The Staff of Hermes, also known as a caduceus, is a reference to ancient Greek mythology. Hermes was messenger of the gods, as well as the god of travel, trade, and diplomacy. The caduceus in Sor Juana’s frontispiece could signal her relation to diplomacy and imperialism of the Spanish Empire. Including this ancient Greek symbol of travel and trade links Sor Juana to Europe and nods to her classical intellectual heritage. The globe likewise symbolizes travel and reinforces the frontispiece’s theme of colonial expansion and exchange.

To either side of Sor Juana are two soldiers that represent conventional allegories of Europe and America. The soldier symbolizing “Europa” on the left is formally dressed in military gear and gladiator sandals. He holds a spear and shield to convey Europe as a civilized continent with advancements in armor and weaponry. His proud stance, looking up and slightly puffing out his chest, further signals European conquest. The soldier on the right, labelled “America,” represents a stereotypical image of the New World, appearing in a skirt with his torso and feet bare. His weaponry, a bow and arrows, suggest the perceived technological inferiority of native Mexican peoples at the time. Compared to Europe, he is posed more demurely, with a downward gaze and hand to his chest in a gesture reminiscent of the classical Venus pudica.

Other details, however, lessen the sartorial and behavioral opposition of the two soldiers. For example, both figures are rendered with the same skin tone and facial features. This is unusual for early modern Western depictions of race. As in painted or sculpted allegorical series of the four continents, for example, European artists tended to misrepresent physiognomic and cultural differences between European and New World peoples to the point of caricature.

It is possible that Caldevilla was familiar with Sor Juana’s work and had her previous writings in mind when he designed the frontispiece to Fama y obras póstumas. In Loa, the prologue play to her Divine Narcissus, Sor Juana portrays allegorical characters named America and Occident, as native to the Americas, and European characters named Zeal and Religion (see Section 4.8 below). One can imagine that in a performance of Loa, these characters would have been costumed like the stereotypical allegories on her posthumous frontispiece. As the narrative of Loa progresses, these characters transition from a combative to a more constructive dialogue about native and Christian belief systems.

Similarly, by positioning Sor Juana between the two soldiers, the 1700 frontispiece signals her interest in merging of European and indigenous American customs. It communicates her religious ties to Spain, as a member of Saint Jerome’s Order, and her life in Mexico City. This placement alludes to her bridging of different worlds: Sor Juana used her teachings with European religious and academic roots to help form an intellectual community in the Spanish viceroyalty. In 1700, her Fama y obras póstumas del fénix de México was published in Madrid with the help of Juan Ignacio de Castorena y Ursúa. This publication spread awareness of New World literary achievements like Sor Juana’s and fostered intellectual networks with Spain (Robles 2021, p. 62-63).

Finally, underneath Sor Juana is a banner that reads: “Unde Lix [Lux] Ardet,” “Gemino petit aethera colle,” “Inde Nix Lucet.” This loosely translates to: “Whence light burns,” “The twin peaks [of Parnassus] soar to heaven,” “The snow shall shine” (The Princeton University Dante Project 2011, https://dante.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/dante/DispCommentByTitOrId.pl?EDIT=1&INP_ID=249786). This is an excerpt from the epic poem Pharsalia written by the Roman poet Lucan in the 1st century C.E. The line is a reference to Mount Parnassus in central Greece. Between the twin peaks of Parnassus was Delphi, considered the center of the classical world and the home of the nine Muses. The phrase in Sor Juana’s frontispiece could nod to her position between the “two peaks” of the Old and New Worlds. It also implies that she occupies Delphi, a fitting residence for the “Tenth Muse.”

After this first main period around 1700, Sor Juana’s works experienced a profound revival of interest during the 20th century. This interest led Mexican literary scholars such as Manuel Toussaint and Emilio Abreu Gómez to publish some brief selections of her poems in the 1920s and 1930s. A more substantial selection of her works was edited by Antonio Castro Leal, which includes her theater and prose works. This edition was published by Editorial Porrúa in 1948 and was republished numerous times.

The most authoritative edition of her complete works was edited and published by the Catholic priest and literary scholar Alfonso Méndez Plancarte (1909–1955), who introduced, edited and annotated the first three volumes published by the Fondo de Cultura Económica (FCE) in Mexico City (1951–52, 1955). The first volume includes Sor Juana’s lyrical poetry, the second her villancicos and other religious poetry, and the third her religious plays (the autos and loas). Méndez Plancarte was unable to complete his editorial work on the last volume due to an untimely death. The fourth and last volume of Sor Juana’s Obras Completas was published in 1959 under the direction of Alberto Salceda, and contains her secular plays, the Neptuno Alegórico, and her prose pieces. The first volume of this collection was recently re-edited in 2009 under the direction of Antonio Alatorre, who addressed some of its lacunae. To this day, the Méndez Plancarte and Salceda edition of Sor Juana’s complete works (along with the re-edited first volume prepared by Antonio Alatorre) remains the best scholarly edition of Sor Juana’s complete works.

There is another edition of her complete works which has been introduced by Francisco Monterde. This edition, originally published by Editorial Porrúa in Mexico City in 1969, has undergone multiple reprints. Subsequent partial editions of her works typically follow the texts established by Méndez Plancarte and Salceda, though there are facsimile editions of the original publications of Inundación Castálida, Segundo Volumen, and Fama y Obras Póstumas that were reprinted by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 1995.

2.1 Major Works

Cruz, Sor Juana Inés de la. 1689. Inundación castálida de la única poetisa. Madrid: Juan García Infanzón.

—. 1692. Segundo tomo de las obras de sóror Juana Inés de la Cruz. Sevilla: Tomás López de Haro.

—. 1700. Fama y obras póstumas del fénix de México. Madrid: Manuel Ruiz de Murga.

2.2 Critical Editions

Cruz, Sor Juana Inés de la. 1916. Poesías escogidas, edited by Manuel Toussaint. México: Imprenta Victoria.

—. 1928. Obras escogidas, edited by Manuel Toussaint. México: editorial Cvltvra.

—. 1928. Primero sueño, edited by Ermilo Abreu Gómez, Contemporáneos (México) I, 272–313, II, 46–54.

—. 1941–1948. Poesías completas, ed. popular revisada por Ermilo Abreu Gómez. México: Botas.

—. 1940. Poesías escogidas, edited by Francisca Chica Salas. Buenos Aires: Estrada.

—. 1940. Poesías (selectas), edited by Ermilo Abreu Gómez. México: Botas.

—. 1944–1988. Poesía, teatro y prosa, edited by Antonio Castro Leal. México: Porrúa.

—. 1951. Obras Completas, tomo I, edición y notas de Alfonso Méndez Plancarte. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

—. 1952. Obras Completas, tomo II, edición y notas de Alfonso Méndez Plancarte. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

—. 1955. Obras Completas, tomo III, edición y notas de Alfonso Méndez Plancarte. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

—. 1957. Obras Completas, tomo IV, edición de Alberto G. Salceda. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

—. 1953. Primero sueño, ed. de la Sección de Literatura Iberoamericana de la Universidad de Buenos Aires, con la colaboración de Juan Carlos Merlo, nota preliminar de Gerardo Moldenhauer. Buenos Aires: Imprenta de la Universidad.

—. 1968. Obras escogidas, edited by Juan Carlos Merlo. Barcelona: Bruguera.

—. 1976. Obras selectas, edited by Georgina Sabat de Rivers y Elias L. Rivers. Barcelona: Clásicos Noguer.

—. 1979. Respuesta a Sor Filotea, edited by Grupo Feminista de Cultura. Barcelona: Laertes.

—. 1979. Florilegio, edited by Elías Trabulse. México: Promexa.

—. 1982. Inundación castálida, edited by Georgina Sabat de Rivers. Madrid: Castalia.

—. 1986. Carta de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz a su confesor: autodefensa espiritual, edited by Aureliano Tapia Méndez. Monterrey: Impresora Monterrey; Reimpreso (1993). Monterrey: Producciones Al Voleo / El troquel.

—. (1987). «La carta de Sor Juana al P. Núñez (1682)», estudio de Antonio Alatorre en Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, t. XXXV, núm. 2. México: El Colegio de México, 591– 673.

—. (1989). El sueño, edited by Alfonso Méndez Plancarte. México: UNAM / Biblioteca del estudiante Universitario.

—. (1989). Fama y obras póstumas de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, edición facsimilar de la edición de 1714, Imprenta de Antonio González de Reyes, edited by Fredo Arias de la Canal. México: Frente de Afirmación Hispanista.

—. (1989). Obras completas, prológo y edición Francisco Monterde. México: Porrúa.

—. (1989). Los empeños de una casa, edición, estudio, bibliografía y notas Celsa Carmen García Valdés. Barcelona: PPU.

—. (1990). La segunda Celestina, edited by Guillermo Schmidhuber. México: Vuelta.

—. (1993). Invndacion Castalida de la vnica poetisa, mvsa décima Soror Jvana Ines de la Crvz, facsímile de la edición española de 1689. Introducción y reseña histórica por Aureliano Tapia Méndez, estudio, índice analítico y concordancia con las Obras completas por Tarsicio Herrera Zapién. Toluca: Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura.

—. (1994). Enigmas ofrecidos a la casa del placer, edited by Antonio Alatorre. México: El Colegio de México.

—. (1994). The Answer/La Respuesta, ed. crítica y trad. Electa Arenal y Amanda Powell. New York: The Feminist Press.

—. (1995). Carta Atenagórica, ed. facsimilar de la primera edición, 1690, Puebla de los Ángeles, imprenta de Diego Fernández de León, prólogo de Elías Trabulse. México: CONDUMEX.

—. (1995). Enigmas ofrecidos a la Casa del placer, edición y prólogo de Antonio Alatorre. México: El Colegio de México.

—. (1995). Fama y obras póstumas, edición facsimilar tomada de la edición de Madrid, 1700, introducción de Antonio Alatorre. México: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional Autonóma de México.

—. (1995). Inundación castálida, ed. facsimilar tomada de la edición de Madrid, 1689, presentación de Sergio Fernández. México: UNAM.

—. (1995). Obra selecta, selección y prólogo de Margo Glantz, cronología y bibliografía de María Dolores Bravo, t. I y II. Caracas: Ayacucho.

—. (1995). Segundo volumen de las Obras de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y la Segunda Celestina, ed. facsimilar tomada de la edición de Sevilla, 1692, Prólogo de Margo Glantz. México: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras / UNAM.

—. (1998). Amor es más laberinto, prólogo de Margo Glantz, Buenos Aires, Impsat.

—. (2004). Obras completas de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz en Cd-Rom, Rosario. Argentina: ediciones Nueva Héla. También se localiza en la Biblioteca editorial Libro electrónico.

—. (2014). El sueño, edición y prólogo de Roberto Echevarren. Montevideo: Colección La flauta mágica.

—. (2014). Nocturna, más no funesta. Poesía y cartas, edición, prólogo y notas de Facundo Ruiz. Buenos Aires: Corregidor.

—. (2016). Selected works, edited by Anna More and translated by Edith Grossman, New York: Norton.

3. Secondary Sources Guide

Arenal, Electa and Stacey Schlau. 1989. Untold Sisters: Hispanic Nuns in their own Works. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Aspe Armelle, Virginia. 2018. Approaches to the Theory of Freedom in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Queretaro: Aliosventos Ediciones.

Benítez, Laura. 1994. “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y la filosofía moderna.” In La literatura novohispana. Revisión crítica y propuestas metodológicas., edited by J. Pascual Buxó y A. Herrera. México, UNAM.

—. 2020. Sensibility and Understanding in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. In Feminist History of Philosophy: The Recovery and Evaluation of Women’s Philosophical Thought. Edited by Eileen O’Neill and Marcy Lascano. Cham: Springer, 75–98.

Bergmann, Emilie L. and Stacey Schlau. 2017. “Introduction: Making and Unmaking Myth in Sor Juana Studies.” In The Routledge Research Companion to the Works of Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz. Edited by Emilie L. Bergmann and Stacey Schlaw. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, ix–xx

Beuapied, Aída. 1996. “El silencio hermético en Primero Sueño a la luz de la figura y las ideas de Giordano Bruno.” Hispania 79 (4): 752–61.

Beuchot, Mauricio. 1982. “Poesía y filosofía escolástica en Sor Juana.” Literatura Mexicana 3 (1): 269–81

—. 2001. Sor Juana. Una filosofía barroca (2nd ed.). Toluca: UAEM/CICSyH.

Boyle, Catherine. 2016. “Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz: The Tenth Muse and the Difficult Freedom to Be.” In A History of Mexican Literature, edited by Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado, Anna M. Nogar, José Ramón Ruisánchez Serra, 66-80. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buxó, Pascual. 1989. “Sor Juana Egipciana: Aspectos Neo-Platónicos de El Sueño.” Mester 18 (2): 1–17

Calvo, Hortensia and Beatriz Colombi. 2015. Cartas de Lysi. La mecenas de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz en correspondencia inédita. Madrid, Frankfurt, México: Iberoamericana, Vervuert, Bonilla

Cañeque, Alejandro. May 3, 2017. “The Empire and Mexico City.” In The Routledge Research Companion to the Works of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Routledge. Accessed on March 26, 2020.

De la Peña, Ernesto. “Villancicos de Sor Juana.” Programa Música para Dios. Uploaded YouTube 2018, Accessed on January 6, 2021. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rX1Z2itNKYc.

Embassy of Mexico in India. “The First Feminist of the New World: Sor Juana.” Medium. Published March 8, 2018. URL: https://medium.com/@embamexindia/the-first-feminist-of-the-new-world-sor-juana-5ea22b35ca9.

Juana, I. C., Garrido, G., Flores, A., Tardio, G. B., Durán, M. A., Araujo, J., Mesa, Cor Vivaldi. 1999. Le phénix du Mexique: Villancicos de Sor Juana Inès de la Cruz. France: K617.

Gaos, José. 1960. “El sueño de un sueño.” Historia Mexicana, 10 (1): 54–71.

Glantz, Margo. 1996. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: saberes y placeres. Toluca: Estado de México: Gobierno del Estado de México, Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura.

Gonzalez Díaz, Marta. 2012. “Reflexiones sobre Primero Sueño de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” Lingüística y Literatura 61: 343–55.

Grossi, Verónica. 2007. Sigilosos v(u)elos epistemológicos en Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Madrid: Iberoamericana; Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert.

Kennet, Frances. 2000. “The Theology of The Divine Narcissus.” Feminist Theology 9 (25): 56–73.

Kirk, Stephanie. 2017. “The Gendering of Knowledge in New Spain: Enclosure, Women’s Education, and Writing.” In The Routledge Research Companion to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Edited by Emilie Bergmann and Stacey Schlau.

—. 2016. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and the Gender Politics of Knowledge in Colonial Mexico. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

López Cámara, Francisco. 1957. “La conciencia criolla en Sor Juana y Sigüenza.” Historiografía Mexicana 6 (3): 350–73.

Moreno, Rafael. 1980. “La filosofía moderna en la Nueva España.” In Estudios de historia de la filosofía en México, (3rd ed.). México: UNAM, 123–32.

Noddings, Nel. 1984. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Olivares Zorrilla, Rocío. 2014. “Sor Juana y Nicolás de Cusa.” Hipogrifo 2 (2): 107–25.

Paz, Octavio. 1990. Sor Juana. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

—. 1987. Sor Juana, o, Las trampas de la fe. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Peden, Margaret Sayers. 1982. A Woman of Genius: The Intellectual Autobiography of Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz. Salisbury, CT: Lime Rock Press.

Poot Herrera, Sara. 1998a. “Las cartas de Sor Juana: públicas y privadas.” In Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y sus contemporáneos, edited by Margo Glantz. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y Centro de Estudios de Historia de México Condumex, 291–317.

—. 1998b. “Una carta finamente calculada: la de Serafina de Cristo.” In Sor Juana & Vieira, trescientos años después, Anejo de la revista Tinta, edited by K. Josu Bijuesca y Pablo A. J. Brescia. Santa Barbara, CA: University of Santa Barbara, 127–41.

Robles, José Francisco. 2021. Polemics, Literature, and Knowledge in Eighteenth-Century Mexico: A New World for the Republic of Letters. Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Rodríguez Garrido, José Antonio. 2006. La Carta Atenagórica de Sor Juana. Textos inéditos de una polémica. Mexico City: UNAM.

Sabat-Rivers, Georgina. 1976. “Sor Juana y su Sueño: antecedentes científicos en la poesía española del Siglo de Oro.” Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos 310: 186–204.

—. 1992. “Sor Juana: imágenes femeninas de su científico Sueño.” In her Estudios de literatura hispanoamericana. Lecturas Hispánicas y Universales, no. 6. Barcelona: Promociones y Publicaciones Universitarias, 305–326.

Soriano Valles, Alejandro. 2000. El Primero Sueño de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: bases tomistas. Mexico City: UNAM/Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas.

Stavans, Ilan. 2018. Sor Juana or, the Persistence of Pop. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press.

Tenorio, Marta Lilia. 1999. Los Villancicos de Sor Juana. Mexico City: El Colegio de México.

—. 2019. «Góngora y sor Juana: una vez más» Cátedra Góngora. YouTube Recording, Accessed June 2020, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C0t8YgdaZ3I.

“The Princeton Dante Project (2.0) – Commentary Par I 16-18.” Princeton University. The Trustees of Princeton University. Accessed November 22, 2021. URL: https://dante.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/dante/DispCommentByTitOrId.pl?EDIT=1&INP_ID=249786

Trabulse, Elías. 1982. El círculo roto: estudios históricos sobre la ciencia en México. México City: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Vossler, Karl. 1953. “Introducción.” In Primero Sueño. Buenos Aires: University of Buenos Aires Press.

Xirau, Ramón. 1970. Genio y figura de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (2nd ed.). Buenos Aires: University of Buenos Aires Press.

Wirzba, Norman. 2003. Neither Saints nor Sinners: Writing the Lives of Women in Spanish America. New York: Oxford University Press USA.

4. Philosophy & Teaching

Before reviewing Sor Juana’s works for their philosophical contributions, it is important to briefly consider some of the main philosophical influences that played a role in the articulation of her views. Since Sor Juana was extremely well read—in fact, it is likely that her personal library was, at some point, the most extensive one on the American continent—her writings are filled with references to classical and medieval figures, as well as references to authors from her own time period. Unfortunately, her library was dispersed after her death, so we cannot conclusively establish which books it contained. Various scholars have, however, been able to identify some of her influences. For instance, scholars such as Karl Vossler (1953), Elías Trabulse (1982), José Pascual Buxó (1989), and Aída Beaupied (1996) have noticed and studied the influence of Hermetic and Neo-Platonic authors in her work, stressing existing parallels between recurring themes in Sor Juana’s writings and themes articulated in the Hermetic Corpus as well as in figures such as Giordano Bruno and Athanasius Kircher. Scholars such as Mauricio Beuchot (1992, 2001) and Alejandro Soriano Vallés (2000) have detailed the influence of Thomas Aquinas on her writings. Virginia Aspe Armella (2018) has stressed the impact of Spanish Scholastic figures, primarily Jesuits such as Francisco Suárez and Luis de Molina, on Sor Juana’s writings. Finally, Laura Benítez (1994, 2020) has emphasized that many of Sor Juana’s writings exhibit a strong critical attitude, always initially directed at herself, that bears strong resemblance to the attitudes displayed by Bacon, Montaigne, and Descartes, while others such as José Gaos (1960), Ramón Xirau (1970) and Rafael Moreno (1995) outline her apparent Cartesian methodological modernism. Scholars in sister disciplines have outlined the vast array of her poetic and literary influences, particularly her roots in the Spanish Baroque, and some scholars have begun to inquire into her potential influences from pre-Columbian sources.

Sor Juana’s philosophical contributions are generally not presented in a systematic and unified fashion within single monographs. Instead, they are distributed among the many writings she penned throughout her life, which span multiple genres including prose, many forms of verse, allegorical and narrative drama, correspondence, and spiritual exercises. For the sake of offering a tentative, if incomplete, taxonomy of her thought, we proceed in the following fashion. We begin with a general overview of her two most important and well-known works, namely, First Dream and the Reply to Sor Filotea. We focus on offering a brief account of the content of each work, detailing the influences that shaped Sor Juana’s writing, presenting the main philosophical themes that emerge in each text, and highlighting some of the central philosophical questions that are raised and addressed by both pieces. Following this, we offer a brief treatment of Sor Juana’s Spiritual Self-Defense, which provides additional autobiographical context and furthers a conception of Sor Juana as a self-determining figure with feminist convictions, capable of standing up for herself and her own rights. After this general overview of her two major works and major epistolary essay, we present a number of other, lesser-known texts in which we find more of Sor Juana’s interesting contributions to philosophy. We first address her views on value theory, beginning by discussing her views on ethics and moral psychology as they appear in various works such as the philosophical-moral sonnets, her secular plays The Trials of a House and Love is a Labyrinth, and a selection of her work in verse.

After covering Sor Juana’s contributions to value theory, we offer an overview of her conception of a good ruler as presented in her unusual piece Allegorical Neptune, highlighting the character traits which she suggests a good prince should have, how these character traits can be cultivated, and what type of relationships a ruler should have with his or her subjects and with God. Subsequently, we discuss Sor Juana’s views on philosophical theology as they are articulated in the Critique of a Sermon, or Letter Worthy of Athena, focusing on her arguments regarding the significance of Christ’s sacrifice and why humans should love God, even if their love does not bring any benefit to God. We then discuss Sor Juana’s allegorical play Divine Narcissus and its Loa, or prologue. We suggest that Sor Juana articulates in the Loa a conception of the Indigenous groups of the American continent as rational beings that are susceptible to arguments to abandon idolatry and worship the true God, and begins to construct her own self-understanding. We then suggest that in the headlining play Divine Narcissus, Sor Juana toys with allegorical juxtapositions to offer alternative conceptions of the Eucharist, the Trinity, and the true requirements of piety. We then consider Sor Juana’s devotional exercises, which contain moral and theological reflections. Finally, we turn to examine a series of pieces in which Sor Juana discusses the nature of music and establishes important connections among poetry, food, and cooking in order to examine Sor Juana’s views on beauty and art.

Sor Juana’s Villancicos and Music

A vast number of Sor Juana’s surviving pieces are villancicos, which may be referred to as carols, and the entire second volume of her four volumes of collected works is dedicated to them. She composed them periodically at the request of important clergy-members and dignitaries throughout her writing career. The present analysis will but skim the depths of these brief but often overlooked parts of Sor Juana’s oeuvre, of which Martha Lilia Tenorio (1999) says she was “the queen” beginning in the 1670s (46), surpassing her contemporaries in “both quantity and quality” of composition (58).

Firstly, let us discuss the choral form of the villancico. These pieces were meant to be sung, generally at religious and sometimes at laic political festivals and services. They were variously intended for evangelizing the audience or for entertaining and involving them in the proceedings. Given the repetitive topics of festivals and services over the arc of years, they generated and invited clever wordplay and intellectual games to keep the ideas fresh. Because of their relative playfulness, even thorny theological issues and paradoxes could be approached by the clever poet.

Sor Juana’s villancicos distinguish themselves for their virtuosity and experimentalism, wide selection of themes, celebration of divine femininity, use of languages including Latin, Spanish, Portuguese, Nahuatl and Castilian vernacular, and distinctive, erudite, and playful authorial voice. Sor Juana herself seemed indifferent to her achievements and prolific output in the medium (Tenorio 1999, 53–54), perhaps seeing these poems as minor works. Nonetheless, her continual composition of these popular carols probably allowed her to maintain amicable political relations with the powerful bishops who requested them (Alatorre 1986), as well as gave her public recognition and, in effect, an independent source of income (Tenorio 1999, 56).

The relative lightheartedness of these pieces suggests that Sor Juana would have been less compelled to tiptoe around her more provocative ideas surrounding the human soul and the spiritual being of Saints, and in fact even came to parody topics she treats seriously elsewhere, such as the major demonstration of Christ’s love. Sor Juana’s poems variously contain playful musings on astronomy, logic, the culinary arts, mathematics, language, music, ethics, freedom, hagiography, theology, epic poetry, history, and more besides. Our ability to distill Sor Juana’s genuine views on any topic from her villancicos, however, remains unclear, due to the formulaic demands and constraints of the medium (Tenorio 1999, 64). We can, however, explore how certain kinds of imagery or analogy show up multiple times in her work, such as her emphasis of feminine divinity, universality of moral and aesthetic goods, and the importance of corporeal reality. We can also explore how she employs and invents certain kinds of poetic moves, demonstrating her resilient and witty character, as well as her knowledge of both her medium and the jargon she exploits for her wordplay. She also uses tropes typical to villancicos of the time distinctively, such as the usually comical treatment of the imagined Black participants, resigning themselves to conditions of slavery in their corporeal condition in the hope of eventual emancipation in the afterlife, a theme that is given a more somber and sympathetic grounding in Sor Juana’s writing.

For the sake of brevity, we will focus on her musical inclinations and what role the villancicos can play in divulging them. Sor Juana could play musical instruments, as she tells us herself in her Reply to Sor Filotea. She even composed a treatise on music theory, which she refers to in a poem to the Vicereine (De la Cruz 2010, 30), though it is sadly now lost. Sor Juana tells us that she developed a view and method for practicing music based on the image of harmony as a spiral, or caracol, an indication that she had a mathematical basis for her theory, and perhaps philosophical roots in either Pythagorean or even Nahua aesthetics. In addition to these examples, we surmise that Sor Juana’s villancicos were virtuosic in part because she actively worried over their appropriateness for performance and strove to make musical innovations. Conductor Antonio de Salazar wrote that he enjoyed putting Sor Juana’s verses to music because they allowed him to show off (60). Sor Juana achieved international fame for her compositions, as we have evidence that they were performed in Bolivia after her death and therefore likely in other places as well (Le phénix du Mexique: Villancicos de Sor Juana Inès de la Cruz 1999). The aesthetic impact of music on Sor Juana’s value theory, we can speculate, is therefore quite large. From various poems it is evident that for Sor Juana, the beautiful and harmonious are often bound together, and that the Good can be heard as well as seen. Further study of her villancicos should prove fruitful to those interested in aesthetics.

Sor Juana and Cooking

The relatively recent discovery of an 18th-century cookbook from the Convent of San Jerónimo, at which Sor Juana was cloistered, which contained an introductory sonnet apparently signed with her name, quickly brought suggestions that it might have been written by Sor Juana herself or copied by her from a larger Convent cookbook. While opinions remain divided as to whether the document genuinely derives from Sor Juana, or whether she may have helped the cooks transcribe their recipes or perhaps concocted some of them herself, what does seem apparent is that Sor Juana was fascinated by the magic of the culinary arts.

As she quips in her Reply to Sor Filotea, while she marvels at the distinct properties of egg whites and egg yolks, Aristotle would have written much more of metaphysics had he spent more time in the kitchen. We see evidence, in some of her epistolary poetry, that she could have confected sweets made of tree nuts as well as milled and prepared chocolate. She also gives her friends fish, poultry stew, and caramels. In her poems she likens cooking to poetry. Both are enabled by the god Apollo, who helps grow seeds and fruits and inspires verse. She also identifies a gift of a ‘measure’ of chocolate to a ‘message’ in ‘measure’ for its recipient. This analogy suggests that Sor Juana saw the arts as aesthetically and perhaps metaphysically unified. For example, in one entertaining poem titled “Bitterest Jill” (“Agrísima Gila”), every part of its subject is described by means of a bitter or sour food, linking a bitter and unpleasant character to bitter and unpleasant edibles, from vinegar and lemons to sour milk and bitter herbs.

In her carols written for Church services, Sor Juana frequently makes use of food as a metaphor for spiritual nutrition and the beauty of the divine. Sor Juana likens the banquet table to the spiritual altar, calling congregants to converge in celebration and nourishment. She also portrays food as a metaphor for the assembling of disparate parts into a cohesive whole. In a few carols called “Salads,” the different poetic voices, sometimes written in different languages, each contribute one part of both the food for the offering and the song for the occasion. For Sor Juana, food can have deeper power still. In one carol for the Assumption, she writes a part for a slave singer, who tries to ply the Virgin Mary with delicious festive foods to delay her ascension into Heaven so that she might instead commune with her worshippers and grant them freedom from their shackles. In a further poem, the sacred oils used in Mass are likened to the oils used for dressing food. Food is thus imbued with the power to rival the attractions of Heaven. In her Loa or prologue to the play Divine Narcissus, she equates the “God of Seeds” of the Aztecs to the God of the Christians, finding parallels in their understanding of God as the source of life and nourishment, and their use of sacrifice and consumption of divine flesh for spiritual advancement.

We cannot be sure how personally invested Sor Juana was in cooking as an activity. However, it seems clear that she championed the art, both in itself and as a feminine pursuit: as she writes in her Reply to Sor Filotea, “What can we women know if not philosophies of the kitchen?” For egalitarian Sor Juana, it seems, traditionally female occupations such as cooking and the simple pleasures of daily life we find in good food are just as promising routes to both scientific inquiry and spiritual fulfillment as those touted by the Scholastic male clergy.

4.1 First Dream

Primero Sueño / “First Dream,” or “The Dream,” sometimes “First, I Dream”

Sor Juana’s poetic magnum opus, Primero Sueño, reflects the Baroque style of her contemporaries, in particular the Spanish Baroque poet Luis de Góngora. For instance, her piece is suffused with metaphors and allegories, creating layers of textual meaning, and is written in silvas, a poetic form composed of varying heptasyllabic and endecasyllabic lines. In theme, narrative progression, and content, Sor Juana’s poem is sui generis, innovating the genre she has taken on (Sabat-Rivers 1976, 1992; Grossi 2007; Gonzalez Díaz 2012; Martha Lilia Tenorio 2019).

Summary

The allegorical poem begins by describing the darkness of night ascending like a pyramid over the world, putting animals to sleep, and allowing the soul to separate from the sleeping body (in Platonic fashion) and ascend toward the heavens to observe the world. The soul seeks universal knowledge, but fails in its initial attempt at total intuitive or sensory knowledge because there is too much to take in. The soul tentatively re-attempts its search for knowledge by using Aristotelian categories of existence; whether this method is successful in the poem remains unresolved. The soul eventually falls back into the body and, incorporated once again, awakens. The final line reveals the gender of the main character: “Yo, despierta” (“I, awake”) as feminine.

Main Issues

The poem is replete with philosophical themes, ranging from the epistemic and metaphysical to the feminist, value theoretic, and theological. The most obvious themes are Platonic—e.g., the positive and productive separation of the soul from the body, the ascent of the soul toward the heavens, and its thirst for universal knowledge stemming from its knowing ignorance—and Aristotelian and Scholastic, e.g., explicit mention of Aristotle’s categories, a Scholastic description of the structure of the body-soul complex, and the idea of incremental, synthetic knowledge being a more productive approach than a wholesale knowing vision. However, there are also clear influences from Hermetic philosophy, for instance, in the mention of the pyramids, an allusion to Jacob’s ladder, and the emphasis on the desire for worldly knowledge as a vehicle for divine knowledge. Some authors note an influence of early modern philosophy on the poem in how it treats skepticism, explores dreaming as an epistemic state, and questions the relationship between empirical and rational processes for learning. Many authors also highlight the extensive feminist concerns of the poem, from the portrayal of the soul as gender-neutral and rational while belonging to a female body, to the emphasis on female mythological figures, particularly ones transmogrified into beasts for infractions against the gods or as protection from male aggression, and the clear gendering of the night as feminine, a time during which it is possible for a woman, like the owl Nyctimene, to intrude on sacred spaces and seek the nectar of knowledge.

Much of the philosophical scholarly treatment of Primero Sueño centers on which themes, influences, or goals are most prominent in this work, and which reveal the true views of its author. One key question, for example, is how optimistic Sor Juana is about the possibility of knowledge, or conversely, to what degree she is committed to skepticism: although the fall of the soul suggests that complete universal knowledge and divine knowledge may be incongruous for mortals, there are hints that some amount of this knowledge is possible. In order to interpret the poem, we must decide how much it reflects Sor Juana’s Baroque influences and how much it demonstrates her innovation on and divergence from its poetic form. Additionally, we might consider which faculties are portrayed as most productive for the pursuit of knowledge: whether the soul is best served by perception or by inference or conceptual synthesis, or whether it benefits from insight or intuition that can only be gained by dreaming.

Another key question concerns the moral dimensions of the pursuit of knowledge. To what degree is Sor Juana embracing or eschewing this pursuit? Is there, in her view, something illicit in the fact that this pursuit takes place at night, away from the divine oversight of the Sun (a metaphor for the Church, perhaps), thus making the soul’s pursuit of knowledge as disobedient and culpable as Eve’s consumption of the apple? Does the pursuit of knowledge necessarily involve an audacity akin to that of Phaeton, to whom the soul is compared in its foolhardy ascent and eventual failure? Or is the ascent of the soul noble and praiseworthy in its intent, turning the image of Phaeton into a romantic tragic hero, and the ambition of the soul into a sincere and divine attribute in keeping with virtuous humility? The polysemous text seems to make room for contrary interpretations, though recent treatments have emphasized the morality of pursuing knowledge, particularly the importance of intellectual and political liberty (González Díaz 2012; Aspe 2018).

4.2 The Reply to Sor Filotea

La Repuesta a Sor Filotea / “The Answer,” or “The Reply to Sor Filotea”

This important prose text is an apologia for (or, defense of) Sor Juana’s intellectual pursuits and for women’s intellectual pursuits as a whole. As Arenal and Powell (2009) note, it is formally structured like a 17th-century legal brief, which emphasizes its significance to Sor Juana’s eventual fate and her own awareness of her precarious situation as a well-known female intellectual facing official censure. Use of irony and textual polysemy contribute to the piece’s various changes in tone: from anxious to defiant, and from self-doubting and self-effacing to confident and bold.

An unauthorized publication of her theological treatise Critique of a Sermon thrust Sor Juana into high-level political polemics and attracted the attention of the Inquisition. In view of the imminent danger of censorship or worse punishment by local Church authorities or the Inquisition itself, Sor Juana wrote Reply to Sor Filotea in order to justify her lifelong pursuit of learning and to make a case for women to be allowed to teach other women. Her Reply joined others’ efforts to defend her, including the former Vicereine rushing to publish the second volume of her works in Spain, and some of her friends giving defenses of their own to her Critique of a Sermon (Calvo and Colombi 2015; Rodriguez Garrido 2004; Poot Herrera 1998a; Paz 1982). Nonetheless, these efforts were ultimately futile in preventing Sor Juana’s eventual renunciation of her intellectual pursuits, the sale of her library and scientific instruments, and her signing in her own blood a promise to focus on divine contemplation in the service of God.

Summary

Sor Juana’s Reply begins with her thanking her interlocutor for publishing Critique of a Sermon, introducing some of the charges she faces, and recasting her pursuit of worldly learning as rooted in humility. She then launches into a biographical recounting of her life as concerns her seeking an education, making a case that her thirst for knowledge is innate and not surmountable by force of will, and that her initial aptitude for education was due not to hubris but to genuine love for God’s world and Word. She then moves to defend her study of humanistic arts (such as rhetoric, poetry, logic, law, and hermeneutics and natural philosophy), suggesting that they are necessary prerequisites to understanding scripture and beginning to consider Theology, and that a genuinely humble servant of God seeks a diligent study of scripture before attending to Theology. Sor Juana supports this argument by referencing Aquinas and the ideas of Kircher, those which characterize proper education as like a ladder and the structure of knowledge as interlinked chains which ultimately lead to God. She then acknowledges her own imperfect grasp of these subjects due to her lack of formal education while again referring to her innate and insurmountable desire to overcome her ignorance and the piousness of this desire. She laments that her intellectual life has brought her fame and public hatred, which she suggests is unjust and akin to the Pharisees’ hatred of Jesus’ virtues: wisdom and the love of wisdom are honorable (which is the only part she claims to possess), but they can inspire jealousy or spite from others.

In the second half of the Reply, Sor Juana relates how she once attempted to give up reading altogether. However, she was not thereby able to cease her learning or inquiry, as the world itself served as her book. That is, she suggests that God desires for us to learn about His work, and that He has everywhere peppered opportunities to investigate it – even in the kitchen, where she jokes Aristotle might have been inspired to write still more than he did. After reiterating the impossibility of controlling her desire to learn, Sor Juana notes a long list of women who achieved public renown for their accomplishments from Deborah and other Biblical figures to the Sibyls and Greek and Roman women to women writing on scripture and various female saints. This launches the penultimate section’s vigorous argument against prohibiting women’s study and interpretation of Holy Scripture: she marshals theology, quoting various Church fathers (particularly Saint Jerome) and theological experts (especially Dr. Juan Díaz de Arce), and philosophy, suggesting that what should matter to the permissibility of study is not birthright but rather virtue, which men can lack as well as women. While reiterating her earlier argument that worldly education is necessary for understanding Scripture, Sor Juana then boldly suggests that, in order to avoid the corruption of young women by men, women should receive an education from other women. Finally, she argues that the permissible erudition of female saints like St. Teresa or St. Gertrude is rooted in a more general permissibility for women to study, since many well-regarded women who have written on scripture are not canonized, and many women in the early Church received educations themselves, whether they became saints or not.

In the last section, Sor Juana defends her specific actions, excusing her poetic writing as generally pious and generated at others’ request. She also frets over the unexpected publication of her Critique by Jesuit priest Antonio Vieyra without her consent, which asserts that the publication was unmerited because her writing was neither very good nor anything more than an unthreatening opinion. Finally, while noting that others have defended her Critique in writing (also without her knowledge), she suggests she will not seek to defend herself directly, preferring to keep silent and receive the criticism of others. She closes with some necessary literary bows and promises to send anything else she writes to her interlocutor for correction first.

Main Issues

The Reply’s central concern is to argue for women’s right to an education, which encompasses the permissibility of Sor Juana’s own intellectual pursuits. To that end, Sor Juana makes many different arguments in both kind and content: appeals to authority, character defense, appeals to precedent, the formulation of new arguments using plausible premises that are both metaphysical and moral, scriptural evidence, theological argumentation, and possibly still others, such as appeals to pathos and pleading a lesser crime than the one charged, e.g., not haughtiness or disobedience, but rather incapacity. Sor Juana believes not only that women should be allowed greater intellectual freedom but also that they should be encouraged to teach each other a great variety of subjects, perhaps even those that men learn and teach. She criticizes the belief that men should be allowed to study Scripture and suggests that men are as prone to error and vice as women are. In this way, she seems to envision a true egalitarianism in the area of learning (although she does not attempt to make a case for women earning any rights held specifically by ordained priests, or leadership positions within the Church, which probably would have been beyond heretical to argue).

Besides the centrality of this feminist or proto-feminist theme, the topics treated in the Reply are quite broad in philosophical scope. One set of prominent issues is epistemological and pedagogical: what is Sor Juana’s view of the structure of knowledge or justification, how are the different disciplines of knowledge arranged, and how deeply committed is she to a Thomistic picture of proper pedagogy? Her text suggests that, because errors in interpreting Scripture can amount to heresy, it is more virtuous to begin learning other subjects, for which infractions are minor (e.g., epistemic or aesthetic mistakes, rather than moral ones). This connects to another question regarding the achievability of divine knowledge: Sor Juana tends to portray the divine not as immediately knowable (certainly not knowable by introspection) in comparison to the mysticism of Saint Teresa or the deductive or intuitive knowledge of God in Descartes. On the whole, Sor Juana’s view seems to be that studying the “profane,” or mundane, arts is not only more permissible, but also more accessible, than studying divine matters. This grounds her pedagogical view: a good education must begin with an education in arts and letters and even in natural philosophy, as this will help make the interpretation of Scripture possible and make it less likely that one will commit heresy by misreading Scripture.

This also pertains to her views on justification. The Reply does not portray the kind of skepticism that seems viable in her First Dream. For example, Sor Juana suggests that her natural inclination towards learning might be God’s doing, as the worldly objects around her that God made each cry out for investigation. This suggests that a certain kind of dogmatism might be warranted, according to which a properly oriented and virtuous subject might be able to attain justified true beliefs about the created material world by the use of their own faculties. Although this requires effort, and similar to a Hermetic perspective (Kircher), the Reply does not portray worldly knowledge as unattainable in the way that it portrays divine knowledge. Some theorists suggest that Sor Juana may have been influenced by the 15th-century theologian Nicholas of Cusa (Olivares Zorrilla 2014), though she does not cite him.