“Women are from their very infancy debar’d those Advantages, with the want of which they are afterwards reproached, and nursed up in those Vices which will hereafter be upbraided to them.”

– A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, pt. I (2nd ed., 1695)

In today’s scholarly context, Mary Astell is most often remembered as England’s first feminist. Indeed, several of her works – especially A Serious Proposal to the Ladies and Some Reflections Upon Marriage – argue forcefully, and with great care, for the basic intellectual equality of men and women. Astell’s biographer, Ruth Perry, shows how the philosopher’s works probably influenced subsequent generations of “learned ladies,” including well-known literary women called bluestockings. She never married, and the overwhelming majority of her close personal connections were with women. After retreating from the public eye during the early 1700s, Astell dedicated herself to the planning and administration of a charity school for girls, evidencing her belief in the cause of women’s education. And yet, much of the secondary literature finds tension in this straightforward assignation of the title of “first English feminist,” for Astell’s other intellectual commitments appear to be in conflict with feminism as we understand it today. In addition to her deeply-held confidence in women’s innate intellectual promise and her thorough explication of the danger of tyrannical husbands, Mary Astell was a high-church Tory, conservative pamphleteer, and advocate for the doctrine of passive obedience, whose strongest political views may have seemed old-fashioned even when they were first published.

It is easy to balk at the contrast between Astell’s faith in the traditional social order and her vigorous espousal of concepts we now recognize as distinctly feminism-flavored, concepts which were rather radical for her time. Instead of dispensing with a feminist analysis of Mary Astell, however, contemporary scholars have worked to understand factors which might have influenced her work as a philosopher, such as Astell’s upbringing, experience of political change, and sociohistorical milieu. As we will see, this approach begins to reveal a Mary Astell who was a careful reader, a lively and witty writer, a passionate Christian, a consistent philosopher, and a profoundly individual thinker in addition to being “a lover of her sex.”

References

- Ballard, George. 1985. Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain: Who Have Been Celebrated for their Writings or Skill in the Learned Languages, Arts, and Sciences. Edited by Ruth Perry. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hill, Bridget, ed. 1986. The First English Feminist: ‘Reflections On Marriage’ and Other Writings by Mary Astell. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Kolbrener, William, and Michael Michelson, eds. 2007. Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

For image sources and permissions, see our image gallery.

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Mary Astell, the firstborn child of Peter Astell and Mary Errington Astell, was born in 1666 in Newcastle. Like his father and brother Isaac, Peter Astell was a coal merchant working in the heart of England’s coal industry, and a clerk in the long-established Hostmen guild. Mary Astell’s mother was the daughter of another well-to-do Newcastle coal merchant. While the Astell family did belong to the gentry, they had attained that status through an ancestor’s augmentation, and their pedigree was only confirmed in the year of Mary Astell’s birth. Mary Astell grew up in relative affluence, as revealed by the 1678 inventory of Peter Astell’s belongings unearthed by Astell’s biographer Ruth Perry in the Newcastle records. Mary Astell’s only surviving sibling, a younger brother also named Peter, eventually became a successful lawyer. Scholars suggest that the combination of the seeming omnipotence of the Newcastle coal trade, Astell’s early experiences of wealth, and her knowledge of her family’s social status may have worked together to lay the foundations of the young intellectual’s developing political ideology. Moreover, Astell witnessed and presumably disliked the political upheaval that gripped Newcastle during the Restoration and the Glorious Revolution.

Astell’s father died when she was twelve years old, and although Mary Errington Astell was not destitute, she struggled to maintain the family’s standard of living. It seems that Astell’s family may not have been able to afford a dowry for her had she wished to marry; some scholars imply that her early religious and scholarly dedication was a partial solution to the problem of female respectability outside of the institution of marriage. Astell moved by herself to London sometime after 1684, seemingly to try her luck as a professional writer (Aphra Behn, of the generation before Astell’s, is considered to have established the legitimacy of a writing career for women in England). Astell settled in Chelsea, where she would live and work for the rest of her life. According to her biographers, Astell’s willingness to attempt an independent scholarly existence sets her apart from some of the other women philosophers of her day.

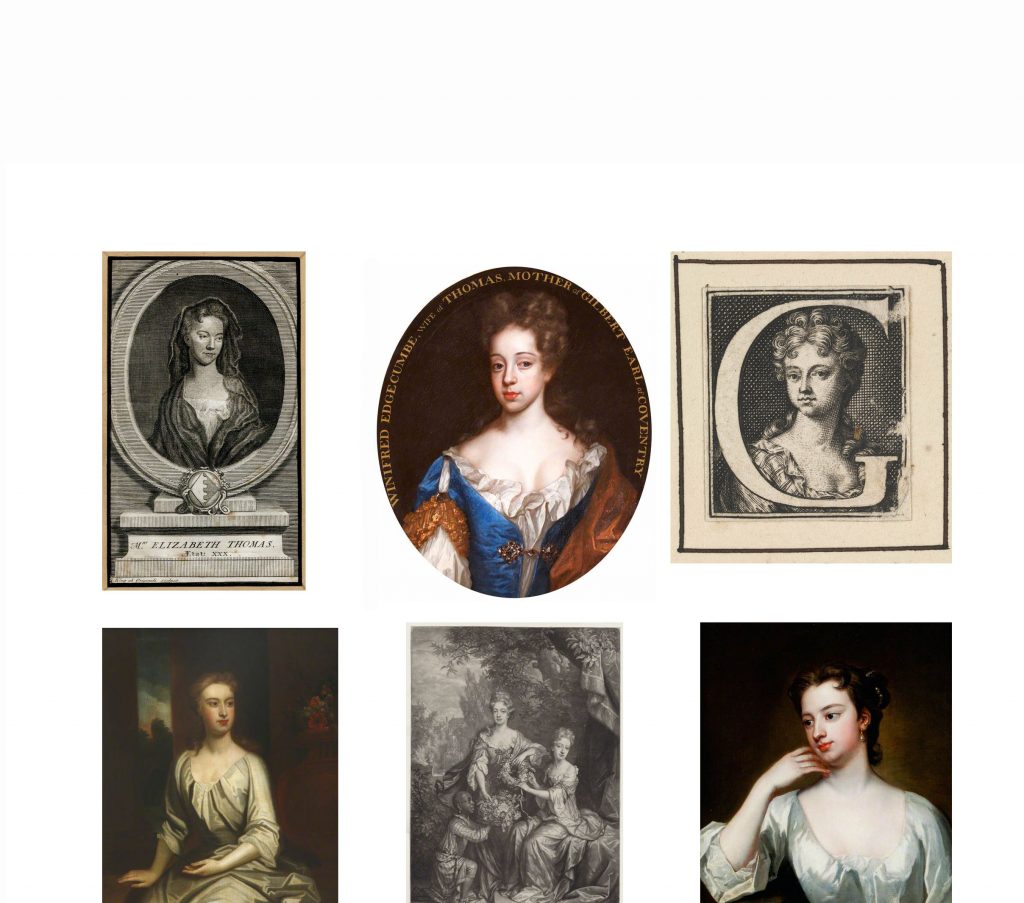

Mary Astell’s relationships were of paramount importance to her, as revealed by her sentimental correspondence and the dedications of several of her publications. As a “poor unknown” in London, however, these connections also benefited Astell in a much more practical way: they helped her support herself. Soon after her arrival in the capital, Astell seems to have reached out to the non-juror and archbishop of Canterbury, William Sancroft, petitioning him to help an impoverished gentlewoman. The Archbishop obliged, providing Astell with funds and contacts, and she later addressed a manuscript of her poems to him, evidently in thanks. Astell probably met Lady Catherine Jones, her closest friend, patron, and the addressee of The Christian Religion, shortly after her move as well, possibly even through Sancroft. Like Astell, Lady Catherine never married, and like most of Astell’s inner circle – including Lady Ann Coventry, Lady Elizabeth Hastings, and Elizabeth Hutcheson – she was wealthy and highborn in a way Astell could never hope to be. The unquestionable aristocratic privilege of these women probably cushioned the vulnerable Astell with a certain amount of social respectability.

One of Mary Astell’s better-known connections was Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a very bright woman born into the generation after Astell and her aforementioned circle. Lady Mary read A Serious Proposal when she was still a young girl; she stands among the well-known bluestockings who may have been influenced by Astell. Mary Astell took an interest in the younger woman, who differed markedly from Astell in temperament in spite of their intellectual affinities. Scholars note that Lady Mary tended to indulge in the pleasures of society, and Mary Astell seems to have taken it upon herself to help steer her friend away from sin. Lady Mary’s granddaughter, Lady Louisa Stuart, provides us with the only known outstanding physical description of Mary Astell (at an advanced age): “This fair and elegant lady of quality, was no less a person than Mistress Mary Astell, of learned memory, the Madonella of the Tatler, a very pious, exemplary woman, and a profound scholar, but as far from fair and elegant as any old school-master of her time: in outward form, indeed, rather ill-favored and forbidding, and of a humour to have repulsed the compliment roughly, had it been paid to her while she lived” (Smith 1916, pp. 15-16).

Mary Astell also befriended Elizabeth Elstob, another well-educated woman who specialized in classics and Anglo-Saxon studies. It was Elizabeth Elstob who provided George Ballard with much of the information about Astell that appears in his biography of her. While Mary Astell took an interest in nurturing her friends’ intellectual lives and seems to have communicated with them in philosophically interesting ways (see the correspondence section), she was also in dialogue, directly and otherwise, with some of the famous public intellectuals of her day.

In 1693, Mary Astell initiated a correspondence with John Norris of Bemerton, a then-famous latter-day Christian Platonist. Astell had read Norris’s Discourses carefully, and appealed to him with a question about an apparent inconsistency in his work on the love of God. Where Norris claimed that everyone ought to love God because He causes our pleasure, Astell noted that God must be the cause of painful sensations as well as pleasurable ones. She wanted to know how this point might square with the rest of Norris’s claims. Their ensuing exchange traced distinctions between desirous and benevolent love. Astell approached Norris respectfully, at times implying that she might appreciate his help in other areas of her intellectual development. Norris recommended some philosophers to Astell – among them the French Cartesian Father Nicholas Malebranche, whose ideas Norris introduced to England – but stopped short of taking her under his proverbial wing. He was impressed by Astell, however, and proposed to publish their correspondence. Astell reluctantly assented, and in 1695 (though some scholars cite 1694) a volume of their letters was privately published. In the volume, Norris takes pains to assure his doubtful readers that his astute interlocutor is indeed a woman.

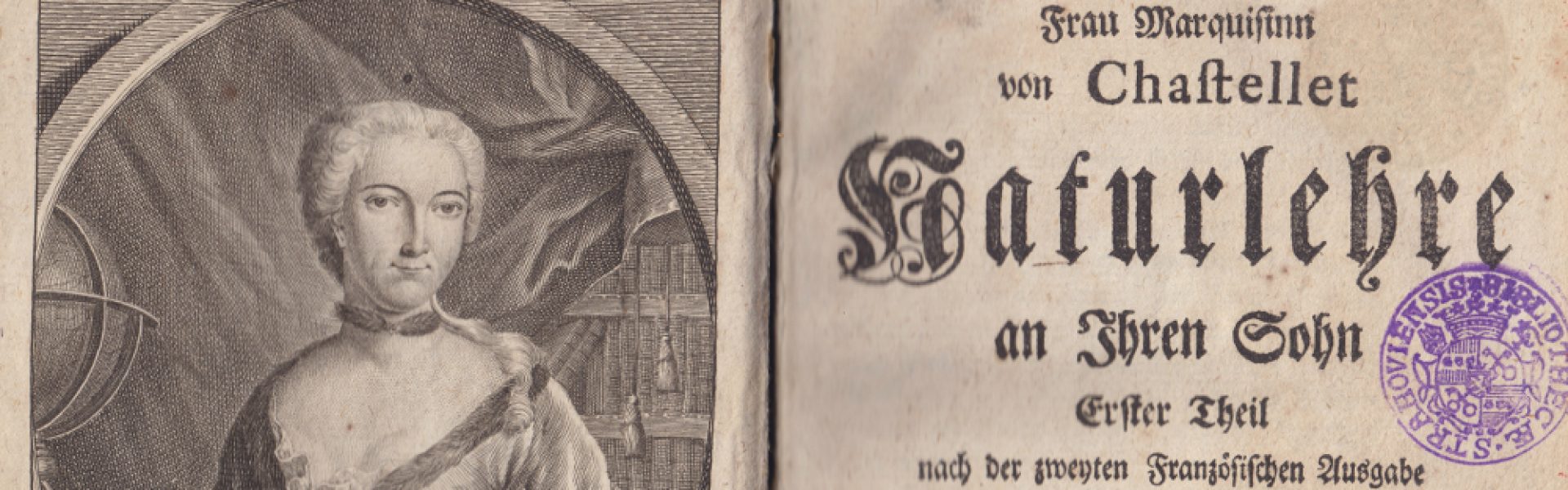

Little is known about Mary Astell’s education, but it seems she was at least familiar with contemporary issues in philosophy before contacting Norris. Astell’s biographers write that her Cambridge-educated uncle, Ralph Astell, likely tutored her during her childhood, but he died when she was still a girl. Her relative poverty and apparent lack of formal education indicate that even more than Conway, Cavendish, or Du Châtelet, Astell was a self-made woman intellectual.

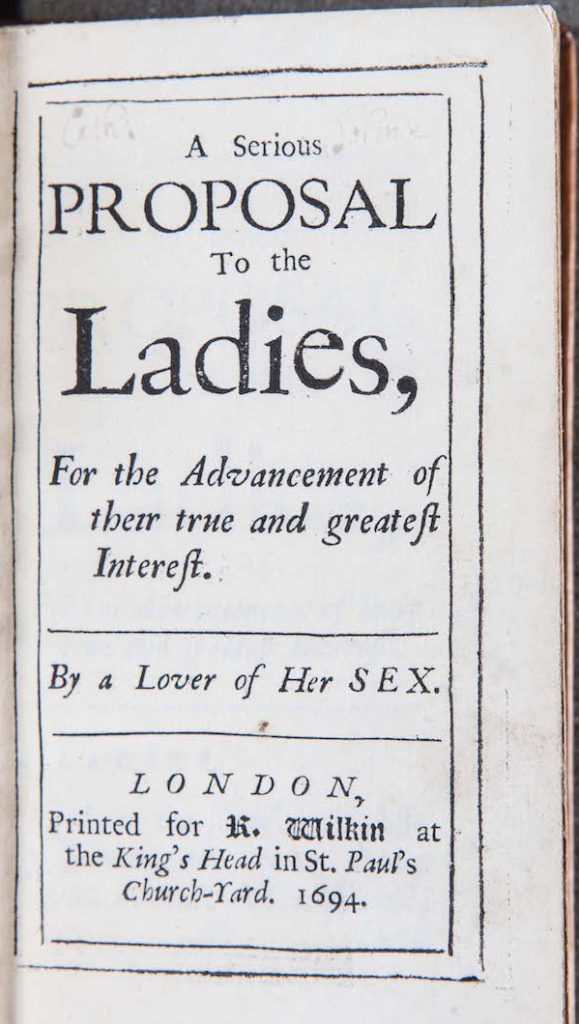

Around the time that her correspondence with Norris was published, the first volume of Mary Astell’s A Serious Proposal to the Ladies (hereafter referred to as SP I) began to gain traction. SP I lays out several arguments against the supposed intellectual inferiority of women, and proposes the establishment of a sort of college (or Protestant convent) where single women might respectably retire, and where young ladies might go to be educated. Astell apparently hoped some wealthy benefactor would take up her cause, but although her ideas generated no small amount of interest, the concept of the college may have seemed too Catholic to its prospective backers. In 1697, Astell published Part II of her Serious Proposal (SP II), this time providing individual ladies with a plan for self-study. SP II also contains the bulk of Astell’s epistemological efforts, which have their roots in Cartesian rationalism. Both volumes went into several editions, and were eventually published as a set.

As Mary Astell garnered fame and admiration for her writing, she also inspired disagreement and even ridicule. She was satirized by Jonathan Swift and Richard Steele in more than one edition of the Tatler, and was probably the (at least partial) target of Susanna Centlivre’s play The Basset Table(1706). In 1714, The Ladies Library was published, which contained several pages of unattributed verbatim text from SP I and SP II, to which Astell took offense. The volume was originally attributed to Steele, but was recently shown to have been published by George Berkeley, the famous Irish philosopher. Interestingly, one of Astell’s main indirect interlocutors appears to have been Lady Damaris Masham, who criticized Astell’s and Norris’s views that God is the sole cause of all causal interactions in the world (occasionalism), and therefore should be the sole object of all our desirous love, in her Discourse Concerning the Love of God (1696). However, there is a scholarly debate as to whether the Masham-Astell exchange was really as adversarial as some scholars have presented it to be. At any rate, it seems that if Astell interpreted the author of Discourse to be a detractor of hers, she probably thought she was engaging with John Locke. The extent to which Mary Astell should be considered an early critic of Locke is the topic of significant scholarly disagreement.

In 1700, Astell’s Some Reflections Upon Marriage was published. This text, which takes the marriage of Astell’s Chelsea neighbor, the unfortunate Duchess of Mazarin, as a case study of a “shipwrack’d” marriage, may provide a good example of the subtlety of argument in which Astell’s feminism is couched. While Astell claims that marriage may be bad for women, she does not call for the dissolution, or even the reform, of the institution itself; since marriage is the only Biblically sanctioned way to perpetuate humanity, it remains necessary for Astell. Some scholars read this text as an ironic satire, while others, notably Patricia Springborg, see it as an argument against the hypocrisy of Whigs who tyrannize their wives while claiming the right to rebel against an unjust state. Either way, Astell argues that although marriage is unlikely to benefit women in the ways they most often expect, it offers an opportunity to improve oneself spiritually through patient Christian suffering.

In 1704, Astell wrote three political pamphlets: Moderation truly Stated; A Fair Way with the Dissenters and Their Patrons; and An Impartial Enquiry into the Causes of Rebellion and Civil War in this Kingdom. During this period, she engaged with several prominent theorists, including Daniel Defoe, on the topics of occasional conformity and the acceptability of dissent.1

The work that is often called Astell’s masterpiece – The Christian Religion, As Profess’d by a Daughter of the Church of England – was published for the first time in 1705. Although Astell lived until 1731, her most widely-distributed work was already behind her by the early 1700s, at least as far as scholars can tell from its public reception and Astell’s publisher’s inventories. She published Bart’lemy Fair: Or, An Enquiry after Wit in 1709, but it seems to have sold poorly and inspired little discussion.

Around this time, Mary Astell embarked on the project that would occupy her until the end of her life. Astell’s charity school for the daughters of pensioners in Chelsea Hospital opened its doors in 1709. As of now there is too little evidence to claim that Astell personally ran the school, but scholars consider it a possibility. Unlike SP I’s proposed college, the Chelsea school imparted practical knowledge to its pupils rather than precepts of abstract reasoning; still, some scholars see the school project as representing the fruition of Astell’s life’s work.

Mary Astell died of breast cancer in 1731 in the home of her dear friend, Lady Catherine Jones. Scholars write that Astell concealed her sickness until she required surgery, which she underwent without anesthesia and with limited success due to the late stage of her tumor. Astell had been seriously ill earlier in her adult life, and at times she wrote of her eagerness for death, but her biographers indicate that she remained active well into her later years. Though she was well-known enough to be both celebrated and satirized during her lifetime, Mary Astell’s prestige eventually faded. From a historical perspective, her conservative political views may have simply lost currency, and her interlocutor John Norris – although he was famous when Astell was alive – is now considered a minor figure in the history of philosophy. Perhaps more importantly, as Jacqueline Broad notes, the overwhelmingly Christian focus of Astell’s treatises may have contributed to her erasure. Although these factors by no means offer an exhaustive account of the reasons for Astell’s comparative anonymity, they probably came together to limit her influence. As a consequence, many of the details of Mary Astell’s life are lost to us. George Ballard, who included her biography in his Memoirs of several ladies of Great Britain, who have been celebrated for their writings, or skill in the learned languages, arts and sciences, apparently had difficulty gathering information for Astell’s entry as soon as 20 years after her death. Nevertheless, many contemporary scholars agree that Astell’s work has much to offer our histories of feminism and of philosophy.

1 Occasional conformity refers to the practice of allowing dissenting would-be politicians to take communion at an Anglican church on an occasional basis in order to be eligible to hold public office. The Occasional Conformity Act of 1711 outlawed this practice, which was the subject of much debate during prior years.

References

- Ballard, George. 1985. Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain: Who Have Been Celebrated for their Writings or Skill in the Learned Languages, Arts, and Sciences. Edited by Ruth Perry. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hill, Bridget, ed. 1986. The First English Feminist: ‘Reflections On Marriage’ and Other Writings by Mary Astell. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Kolbrener, William, and Michael Michelson, eds. 2007. Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.2 Portraits

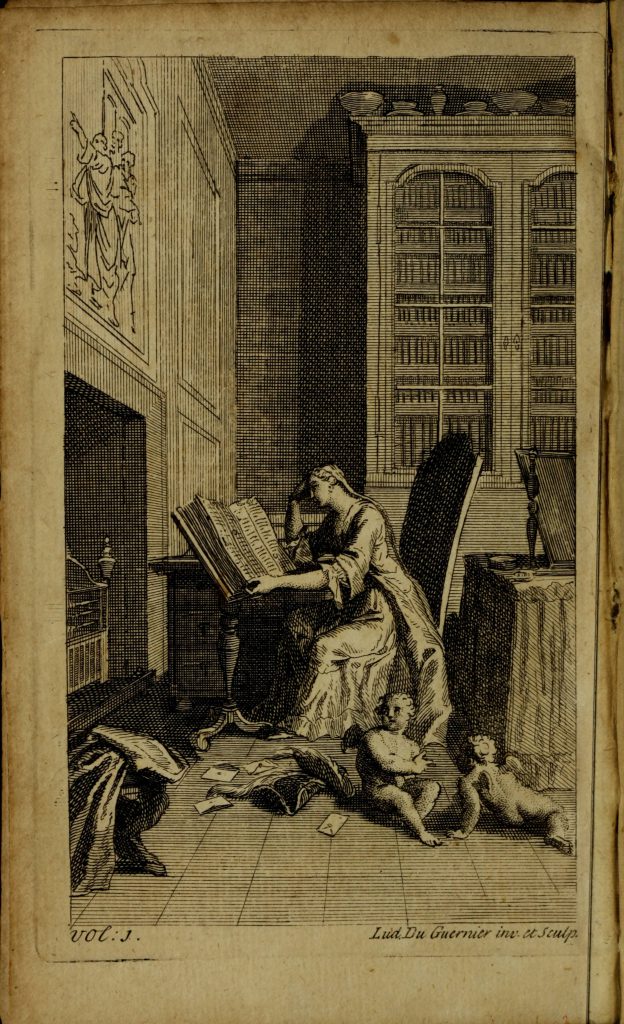

No depictions of Astell are currently extant. It seems unlikely that she would have accepted the expense to commission her own portrait, and since she lacked family from her adolescence onward, she may never have sat for one. Unlike those of Margaret Cavendish, Astell’s books do not include elaborate frontispieces or engravings of their author.

However, Ruth Perry’s authoritative 1986 biography of Mary Astell and Jacqueline Broad’s 2015 monograph on Astell’s philosophy both contain images associated with the philosopher. The cover image of Broad’s The Philosophy of Mary Astell is from The Ladies Library, in which several passages of Astell’s work had been reprinted without citation (to their author’s frustration) in 1714. Perry’s volume contains a number of engravings of places that were relevant to Astell’s life, as well as painted portraits of her friends and acquaintances. She also includes a depiction of an anonymous woman, respectably dressed, perusing a book at her desk. It is possible to imagine that Mary Astell looked something like this.

References

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.3 Chronology

| DATE | EVENT |

| 1666 | Mary Astell was born on November 12, 1666 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne to Mary Errington and Peter Astell. Peter Astell’s membership in an important coal merchants’ guild may have influenced his daughter’s conservative class politics. |

| 1674-1678 (approx.) | Mary Astell’s education begins. Astell received some tuition from her uncle Ralph Astell (a clergyman), and probably acquired a gentlewoman’s education in feminine practices as well. |

| 1678 | Mary Astell’s father, a gentleman and member of an influential coal merchants’ guild, the Hostmen, dies. The Astell family falls into hardship after his death. |

| 1684 | Some sources date Mary Astell’s mother’s death to this year, though Perry suggests she died in 1695. The Mary Astell who died in this year was probably the philosopher’s aunt. Astell moves to London several years later, possibly due to the political turmoil that took place between 1686-1688 in Newcastle. |

| 1688 (?) | Astell moves to London. She likely received initial support from Archbishop Sancroft, who may have introduced her to Lady Catherine Jones. Shortly after moving, Astell established a close circle of friends including Lady Catherine, Lady Ann Coventry, and Lady Elizabeth Hastings. These friends supported Astell socially, and to some extent financially, for the rest of her life. |

| 1689 | Astell completes a manuscript of poetry dedicated to Archbishop William Sancroft, possibly to thank him for his assistance. Ruth Perry suggests that the manuscript would have been lost had it not been dedicated to Sancroft. |

| 21 September 1693 | Mary Astell initiates a correspondence with John Norris of Bemerton. |

| 1694 | Publication of A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, pt. I. |

| 1695 | John Norris publishes Letters Concerning the Love of God, taking pains to assure his readers that his interlocutor was really a woman. |

| 1697 | Publication of A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, pt. II. |

| 1700 | Publication of Some Reflections upon Marriage, a text known today for its proto-feminist content. This work was inspired by the misadventures of Astell’s neighbor and acquaintance, the Duchess of Mazarin. |

| 1704 | Publication of political pamphlet, Moderation truly Stated. The pamphlet chronicles Astell’s position on the Occasional Conformity debate, and was most likely written in response to James Owen’s Moderation A Vertue (1703). |

| 1704 | Publication of political pamphlet, An Impartial Enquiry Into The Causes Of Rebellion and Civil War In This Kingdom. In this pamphlet, Astell claims that the Whigs and Dissenters constitute a great threat to organized society. |

| 1704 | Publication of political pamphlet, A Fair Way with the Dissenters and their Patrons. This text put Astell into dialogue with Daniel Defoe, who was probably familiar with Astell’s earlier works as well. |

| 1705 | Publication of The Christian Religion, as Profess’d by a Daughter Of The Church of England. This text is widely considered to be Astell’s magnum opus. |

| 1709 | Publication of Bart’lemy Fair, which was written in response to Shaftesbury’s A Letter Concerning Enthusiasm. Though Astell probably continued to develop her philosophical views after 1709, Bart’lemy Fair is her latest extant published treatise. |

| 1709 | Astell’s charity school, a school for the daughters of Chelsea Hospital patients and veterans, opens its doors. The school, which operated in its original borrowed premises for 153 years, would dominate Astell’s personal attention and public work for much of the rest of her life. |

| 1714 | Publication of The Ladies Library, in which the volume’s editor (once believed to be Steele, but recently revealed to have been Berkeley) printed excerpts of Astell’s writings verbatim without citing her by name. |

| 1720 | The South Sea stock crisis – in which company Astell had invested at least some of her own money, and possibly some of the funds which had been donated to the Chelsea school – takes place, effectively ending Astell’s hopes of building a permanent location for the school. |

| 1726 | Mary Astell moves in with her dear friend, Lady Catherine Jones. Astell later dies in this house. |

| 1731 | Mary Astell dies of breast cancer on approximately May 11. George Ballard’s account of Astell’s death indicates that she wished to be alone during her final days, communing only with God. She was buried on May 14th at Chelsea. |

| 1752 | Publication of George Ballard’s Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain, which contains the first biography of Astell. Without this work, what relatively little we know about Astell today might have been lost to history. |

References

- Ballard, George. 1985. Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain: Who Have Been Celebrated for their Writings or Skill in the Learned Languages, Arts, and Sciences. Edited by Ruth Perry. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Smith, Florence M. 1916. Mary Astell. New York: Columbia University Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2. Primary Sources Guide

Mary Astell published nine texts between 1694 and 1709. Each of her books saw multiple reprints during her lifetime, and her pamphlets were well-advertised and -distributed.

A Serious Proposal To the Ladies, For the Advancement of their true and greatest Interest. By a Lover of Her Sex. (1694)

Astell’s first book lays out a proposal to establish a “Protestant nunnery” devoted to the education and safe retirement of women. In it, Astell argues that if women might be said to be intellectually inferior to men, it is because of custom only, and not due to any kind of innate inequality. In fact, Astell wonders, how can women be expected to be wise when they are intentionally deprived of an education, and have instead been steered towards distracting and corrupting pursuits? Since God does nothing in vain, all creatures who possess the faculty of rationality ought to work to improve rather than to squander it. The book was well-received; according to some scholars, an unknown woman (possibly Princess Anne or Elizabeth Hutcheson) was inclined to fund the project until someone – probably Bishop Gilbert Burnet – pointed out its undesirably “Popish” aspects. Disappointed, Astell published the second volume of A Serious Proposal, which offered a method for improving one’s own mind, in 1697.

Letters Concerning the Love of God, Between the Author of the Proposal to the Ladies And Mr. John Norris: Wherein his late Discourse, shewing That it ought to be intire and exclusive of all other Loves, is further cleared and justified. (1695)

John Norris was sufficiently impressed with the progress of his eleven-letter correspondence with Astell that he requested to publish it privately in 1695. Scholars agree that this volume shows the young Astell arguing against Norris’s Malebranchean occasionalism, a position which seems to contradict the views presented in her later treatise, The Christian Religion. However, there is scholarly debate about whether or not Astell’s opinions really changed. The bluestocking Sarah Chapone described the Norris letters as Astell’s most “sublime” work (see the letter to George Ballard dated March 12, 1742, Ballard MSS 43:132).

A Serious Proposal To The Ladies, Part II. Wherein a Method is offer’d for the Improvement of their Minds. (1697)

The second part of Astell’s proposal recognized that her idea for a women’s college was unlikely to come to fruition. Instead of dropping the issue of women’s education, Astell offered a plan that could be followed by any person interested in improving her mind. Scholars agree that this text contains the most complete account of epistemology – clearly inspired by the methods of Descartes, Arnauld, Malebranche, and other rationalists – in Astell’s oeuvre, but are divided on the issue of the completeness of her view.

Some Reflections Upon Marriage, Occasion’d by the Duke & Duchess of Mazarine’s Case; which is also consider’d. (1700)

Some Reflections Upon Marriage is one of Astell’s most famous feminist texts, and the preface to its third edition contains some of her most memorable and quotable prose. This book discusses the difficulties of Hortense Mancini, Astell’s neighbor in Chelsea and the Duchess of Mazarin, in her marriage to a cruel and jealous man. While Astell is sharply critical of the prospects for women’s happiness in marriage, she does not advocate for the reform or abolition of the institution. Instead, Astell claims that education will help women either choose better husbands or avoid marriage altogether, and that those who do marry should improve their souls by bearing the hardship with serene Christian faith.

Moderation truly Stated: Or, A Review of A Late Pamphlet Entitul’d Moderation a Vertue. (1704)

This political pamphlet, Mary Astell’s first, contains her response to the Occasional Conformity debate, ostensibly in response to James Owen’s Moderation A Vertue (1703). Its “Prefatory Discourse to Dr. D’Avenant Concerning His late Essays on Peace and War” proved to be very popular.

An Impartial Enquiry Into The Causes of Rebellion and Civil War In This Kingdom. (1704)

More of a royalist manifesto than any of her other works, this piece was written to commemorate the execution of Charles I. In it, Astell claims that the Whigs and Dissenters constitute an incredible threat to organized society, in her view endangering all of England.

A Fair Way With The Dissenters And Their Patrons. (1704)

Written in response to Daniel Defoe’s The Shortest Way With the Dissenters and More Short Ways With the Dissenters (1703, 1704), this pamphlet defends the High Church Tory minister Sacheverell.

The Christian Religion, As Profess’d by a Daughter of The Church of England. (1705)

The Christian Religion is widely held to be the most mature and complete presentation of Astell’s philosophy. Here, Astell continues to develop her arguments against the supposed natural inferiority of her sex, while also presenting her account of the Christian religion. She argues that Christianity is a rational religion, and that since women are capable of rational thought, they are also capable of understanding Christianity for themselves. Arguing against Locke, Masham, and others, Astell also defends her notion of Christian orthodoxy.

Bart’lemy Fair: Or, An Enquiry after Wit (1709)

This treatise responds to Shaftesbury’s A Letter Concerning Enthusiasm, which in Astell’s opinion made light of a matter of life or death: adherence to the true Christian religion.

References

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Please note: the table available below is based in part on Appendix F of Perry’s The Celebrated Mary Astell. Locations of original copies have been independently verified by members of the Project Vox team whenever possible.

Spreadsheet version of table: Excel file (52KB).

| Primary source | Date/Publication Details | Locations of Original Copies |

| early manuscript of poems | ||

| Manuscript of poems inscribed to Archbishop William Sancroft | 1689 | According to Perry, the volume is found in MS Rawlinson Poet 154:51. See also reprinted poems in Appendix D of Perry 1986, 400-454. |

| A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, pt. I | ||

| A Serious Proposal To the Ladies, For the Advancement of their true and greatest Interest. By a Lover of Her Sex. | London, Printed for R. Wilkin at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1694. | Union Library Catalog of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA (online); UCLA, William Andrews Clark LIbrary, Los Angeles, CA; New York State Library, Albany, NY; Alabama State University, Montogomery, AL; University of Colorado at Denver, Denver, CO (online); Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH; Pennsylvania State University, Univeristy Park, PA (online); Virginia State Library, Richmond, VA; University of Texas, Austin, TX; Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT (online); Princeton University, Princeton, NJ (online); Graduate Theological Union, San Anselmo, CA |

| … The Second Edition Corrected. | London, Printed for R. Wilkin, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1695. | Columbia University, New York, NY; (online) University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN; Honnold Librarr, Claremont, CA; Bryn Mawr College Library, Bryn Mawr, PA (microfilm) (online); Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; New York Public Library, New York, NY. |

| A Serious Proposal To The Ladies, For The Advancement of their True and Greatest Interest, Part I. By a Lover of her Sex. The Third Edition Corrected. | London, printed by T.W. for R. Wilkin, at the King’s-Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1696. | Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Stanford University, Stanford, CA (online); Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. (online) |

| … The Fourth Edition. | London: Printed by J.R. for R. Wilkin, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, MDCCI. 1701 | This edition contains both parts I and II. Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (online); Rice University, Fondren Library, Houston, TX. University of Texas, Austin, TX (online) |

| A Serious Proposal To The Ladies, For The Advancement of their True and Greatest Interest, In Two Parts. By a Lover of her Sex. | London: Printed for Richard Wilkin at the King’s-Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1697. | This edition contains both parts I and II. Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY (online); UCLA, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; Union Theological Seminary, New York, NY (online); Newberry Library, Chicago, IL; Boston Public Library, Boston, MA; (online) University of Chicago, John Crerar Library, Chicago, IL (online); University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI (online); Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT (online); Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); Union Theological Seminary, McAlpin Collection, New York, NY; New York State Library, Albany, NY (online); University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (online); Smith College, Northampton, MA. (online) |

| Letters Concerning the Love of God | ||

| Letters Concerning the Love of God, Between the Author of the Proposal to the Ladies And Mr. John Norris: Wherein his late Discourse, shewing That it ought to be intire and exclusive of all other Loves, is further cleared and justified. Published by J. Norris, M.A. Rector of Bemerton near Sarum. | London, Printed for Samuel Manship at the Ship new the Royal Exchange in Cornhil, and Richard Wilkin at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1695. | Whittier College, Whittier, CA (online – HATHI TRUST); University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); Newberry Library, Chicago, IL; Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT (online); University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN (online); Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; University of California at Los Angeles, William Andrews Clark Memorial LIbrary, Los Angeles, CA; University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI (online); Stanford University, Stanford, CA (online); University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC (online); Northwestern University, Evanston, IL. (online); University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online) |

| Letters Concerning the Love of God, Between the Author of the Proposal to the Ladies And Mr. John Norris: Wherein his late Discourse, shewing, That it ought to be intire and exclusive of all other Loves, is further Cleared and Justified. Published by J. Norris, M.A. Rector of Bemerton near Sarum. The Second Edition, Corrected by the Authors, with some few Things added. | London: Printed for Samuel Manship at the Ship near the Royal exchange in Cornhil, and Richard Wilkin at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1705. | University of California at Los Angeles, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA; Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Bethany and Northern Baptist Theological Seminaries Library, Oak Brook, IL; University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online + HATHI TRUST); Memphis State University, Memphis, TN; Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA; Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH (online); University of Chicago, Chicago, IL (online); Athenaeum, Boston, MA; New York Public Library, New York, NY (online); Brown University, Providence, RI (online); University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI; University of Texas, Austin, TX (online resource) |

| Letters Concerning the Love of God, Between the Author of the Proposal to the Ladies And Mr. John Norris: Wherein his late Discourse, shewing, That it ought to be intire and exclusive of all other Loves, is further Cleared and Justified. Published by J. Norris, M.A., late Rector of Bemerton near Sarum. The Third Edition, Corrected by the Authors, with some few Things added. | London: Printed for Edmund Parker at the Bible and Crown over against the New Church in Lombard-Street, 1730. | Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT. UCLA (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online) |

| A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, pt. II | ||

| A Serious Proposal To The Ladies, For The Advancement of their True and Greatest Interest, Part I. By a Lover of her Sex. The Fourth Edition. | London: Printed by J.R. for R. Wilkin, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, MDCCI. | This edition contains both parts I and II. Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati (online), OH; Rice University, Fondren Library, Houston, TX. (online) |

| A Serious Proposal To The Ladies, Part II. Wherein a Method is offer’d for the Improvement of their Minds. | London: Printed for Richard Wilkin at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1697. | Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Univeristy of California at Los Angeles (online access), William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA; Boston Public Library, Boston, MA (online); Stanford University, Stanford, CA. (online) Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. (online) |

| A Serious Proposal To The Ladies, For The Advancement of their True and Greatest Interest, In Two Parts. By a Lover of her Sex. | London: Printed for Richard Wilkin at the King’s-Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1697. | This edition contains both parts I and II. Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY (online); University of California at Los Angeles (online access), William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; Union Theological Seminary, New York, NY (online); Newberry Library, Chicago, IL; Boston Public Library, Boston, MA (online); University of Chicago, John Crerar Library, Chicago, IL (online); University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT (online); Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); Union Theological Seminary, McAlpin Collection, New York, NY (online); New York State Library, Albany, NY; University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (online); Smith College, Northampton, MA. (online) |

| Some Reflections upon Marriage | ||

| Some Reflections Upon Marriage, Occasion’d by the Duke & Duchess of Mazarine’s Case; which is also consider’d. | London: Printed for John Nutt near Stationers-Hall, 1700. | Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT (online); Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; University of California at Los Angeles (online access), William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA; Alabama State University, Montgomery, AL (online); University of Colorado at Denver, Denver, Colorado; Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA; Graduate Theological Union, San Anselmo, CA. + University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online) |

| Some Reflections Upon Marriage. The Second Edition. | London: Printed for R. Wilkin, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1703. | Newberry Library, Chicago, IL; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); Stanford University, Stanford, CA. (online) + University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online) |

| Reflections Upon Marriage. The Third Edition. To which is Added A Preface, in Answer to some Objections. | London: Printed for R. Wilkin, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1706. | University of California at Los Angeles (online access), William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); Washington State University, Pullman, WA (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT (online); Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton, NJ (online); Boston Athenaeum, Boston, MA; Honnold Library, Claremont, CA; New York Public Library, New York, NY; Bryn Mawr College Library, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania (microfilm). + University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online) |

| Some Reflections Upon Marriage. With Additions. The Fourth Edition. | London: Printed for William Parker, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard. M.DCC.XXX.1730 | University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online); Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; New York Public Library, New York, NY (online); Duke University, Durham, NC; (online) Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; Athenaeum of Ohio, Cincinnati, OH; Rice University, Houston, TX (online); University of Vermont, Burlington, VT; Columbia University, New York, NY. + Stanford University, Stanford, CA (online) |

| Some Reflections Upon Marriage. With Additions. The Fifth Edition. | Dublin: Printed by and for S. Hyde and E. Dobson, and for R. Funne and R. Owen, Booksellers. M.DCC.XXX. PUBLISHED IN 1730 | Henry F. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Univeristy of Florida, Gainesville, FL. + University of Illinois, Urbana, IL (online) + Stanford University, Stanford, CA (online) |

| Moderation truly Stated | ||

| Moderation truly Stated: Or, A Review of A Late Pamphlet Entitul’d Moderation a Vertue. With A Prefatory Discourse To Dr. D’Aveanant, Concerning His late Essays on Peace and War. | London: Printed by J.L. for Rich. Wilkin, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard. MDCCIV. PUBLISHED IN 1704 | University of Chicago, Chicago, IL (online access); Indiana University, Lilly Library, Bloomington, IN; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); United States Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; New York Public Library, New York, NY; Union Theological Seminary, New York, NY (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); Yale University, Divinity School, New Haven, CT (online); Boston Public Library, Boston, MA (online); Columbia University, New York, NY. (online) |

| A Fair Way With The Dissenters And Their Patrons | ||

| A Fair Way With The Dissenters And Their Patrons. Not Writ by Mr. L––––y, or any other Furious Jacobite whether Clergyman or Layman; but by a very Moderate Person and Dutiful Subject to the Queen. | London: Printed by E.P. for R. Wilkin, at the King’s-Head, in St. Paul’s Church-yard, 1704. | McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (online); Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Indiana University, Lilly Library, Bloomington, IN; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN; (online) Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; Boston Public LIbrary, Boston, MA. (online) |

| An Impartial Enquiry Into The Causes of Rebellion and Civil War In This Kingdom | ||

| An Impartial Enquiry Into The Causes of Rebellion and Civil War In This Kingdom: In an Examination of Dr. Kennett’s Sermon, Jan. 31. 1703/4. And Vindication of the Royal Martyr. | London: Printed by E.P. for R. Wilkin at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1704. | Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; University of Indiana, Lilly Library, Bloomington, IN; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); Union Theological Seminary, New York, NY (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); California State Library, Sacramento, CA; Princeton University, Princeton, NJ (online); Yale University, Beinecke Library, New Haven (online), CT; New York Public Library, New York, NY; University of Nebraska, LIncoln, NE. (online) |

| The Christian Religion, as Profess’d by a Daughter Of The Church of England | ||

| The Christian Religion, As Profess’d by a Daughter of The Church of England. | London: Printed by S.H. for R. Wilkin at the King’s-Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1705. | University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (online); Trinity College, Haverford, CT (online); Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC; Newberry Library, Chicago, IL; University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); General Theological Seminary of the Protestant Episcopal Church, New York, NY; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (online); University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. (online) |

| The Christian Religion, As Profess’d by a Daughter of the Church of England. | London: Printed by W.B. for R. Wilkin at the King’s-Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1717. | Trinity College, Hartford, CT (online); University of the South, Sewanee, TN (online); University of California at Los Angeles, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA. |

| The Christian Religion, As Profess’d by a Daughter of the Church of England Containing Proper Directions for the due Behaviour of Women in every Station of Life. With a few cursory Remarks on Archbishop Tillotson’s Doctrine of the Satisfaction of Christ, &c. The Third Edition. | London: Printed for W. Parker, at the King’s-Head in St. Paul’s Church Yard. M.DCC.XXX. | Yale University, Divinity School, New Haven, CT. (online) |

| Bartl’emy Fair | ||

| Bart’lemy Fair: Or, An Enquiry after Wit; In which due Respect is had to a Letter Concerning Enthusiasm. To my Lord***. By Mr. Wotton. | London: Printed for R. Wilkin, at the King’s Head in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, 1709. | University of California at Los Angeles (online access), William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, Los Angeles, CA; Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; United States Library of Congress, Washington, DC; University of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (online); University of Oregon, Eugene, OR (online); University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); Oakland University, Rochester (online), MI; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL (online); Yale University (onliine), Beinecke Library, New Haven, CT; Boston Public Library, Boston, MA; Brown University, Providence, RI; (online) Stanford University, Stanford, CA. (online) |

| An Enquiry After Wit: Wherein the Trifling Arguing and Impious Raillery of the Late Earl of Shaftsbury, In his Letter concerning Enthusiasm, and other Profane Writers, Are fully Answer’d, and justly Exposed. The Second Edition. | London: Printed for John Bateman at the Hat and Star in St. Paul’s Church-Yard. MDCCXXII. PUBLISHED IN 1722 | University of Texas, Austin, TX (online); Washington University, St. Louis, MO (online); University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. (online) |

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.1 Modern editions of primary sources

- Broad, Jacqueline, ed. 2013. The Christian Religion, as Professed by a Daughter of the Church of England (The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series). Toronto, ON: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies and Iter Publishing.

- Cottegnies, Line, trans. and ed. 2008. Mary Astell et le féminisme en Angleterre au XVIIe siècle. Lyon, France: ENS Éditions.

- Hill, Bridget, ed. 1986. The First English Feminist: ‘Reflections On Marriage’ and Other Writings by Mary Astell. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Springborg, Patricia, ed. 1996. Astell: Political Writings (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Springborg, Patrcia, ed. 2002. A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, Parts I and II. Petersborough, ON: Broadview Press.

- Taylor, E. Derek, and Melvyn New, eds. 2005. Letters Concerning the Love of God. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

There are several historical sources of note that are contemporary with Astell. The first is George Ballard’s brief biography of Mary Astell that appears in his Memoirs of several ladies of Great Britain. Others reflect the distinction between primary and secondary sources, such as several 19th-century articles about Astell.

References

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

3. Secondary sources guide

Since the mid-20th century, scholarly interest in Mary Astell has increased dramatically, and the range of secondary sources about her life and work has grown in proportion.

Much of the secondary literature addresses the social and political impact of Astell’s philosophy. Additional works that may be of interest to philosophers include Jacqueline Broad’s 2015 book, The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue, which interprets Astell as a moral philosopher who ultimately advances a theory of feminist liberation.

Several recent volumes – especially William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson’s Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith and Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss’s Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell – continue to take seriously Astell’s contributions to her field in ways relevant to contemporary academic philosophy. See the secondary sources bibliography (in Astell §3.1) for additional resources.

Introductory resources

Ruth Perry’s 1986 biography is an excellent starting point for those interested in learning more about Astell. Florence Smith’s 1916 biography may be useful as well. Mary Astell: The First English Feminist, edited by Bridget Hill, contains a helpful biographical introduction as well as excerpts from Astell’s writings. Several works by Jacqueline Broad, including her chapter on Astell in Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century, provide a nuanced overview of Astell’s position as an early modern philosopher; The Philosophy of Mary Astell is especially useful for those seeking a rigorous account of the philosophical content of Astell’s works. Finally, Christine Sutherland’s The Eloquence of Mary Astell offers an accessible overview of Astell’s works, with analysis grounded in the rhetorical tradition of the art of persuasion.

References

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kolbrener, William, and Michael Michelson, eds. 2007. Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Smith, Florence M. 1916. Mary Astell. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sowaal, Alice, and Penny A. Weiss, eds. 2016. Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- Sutherland, Christine M. 2005. The Eloquence of Mary Astell. Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

3.1 Secondary sources

The following represent a selection of secondary sources on Astell.

Downloadable version: PDF file (185KB).

- Achinstein, Sharon. 2007. “Mary Astell, Religion, and Feminism: Texts in Motion.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 17-30. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Ahearn, Kathleen A. 2009. “The Passions and Self-Esteem in Mary Astell’s Early Feminist Prose.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Denver.

- Ahearn, Kathleen. 2016. “Mary Astell’s Account of Feminine Self-Esteem.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Alvarez, David P. 2011. “Reason and Religious Tolerance: Mary Astell’s Critique of Shaftesbury.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 44(4): 475-494.

- Apetrei, Sarah L. T. 2008. “‘Call No Man Master Upon Earth’: Mary Astell’s Tory Feminism and an Unknown Correspondence.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 4(4): 507-523.

- Apetrei, Sarah L. T. 2010. Women, feminism and religion in early Enlightenment England (Cambridge studies in early modern British history). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berges, Sandrine. 2011. “Reason Nipped in the Bud: Freedom and Education in the Vindication of the Rights of Woman (in Turkish).” Felsefe Tartismalari (Philosophical Discussions): A Turkish Journal of Philosophy 46: 18-38.

- Blank, Andreas. 2015. “Mary Astell on Flattery and Self-Esteem.” The Monist 98(1): 53-63.

- Boyle, Deborah. 2011. “Astell and Cartesian ‘Scientia’.” In The New Science and Women’s Literary Discourse: Prefiguring Frankenstein, edited by Judy A. Hayden, 99-112. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2002. Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2003. “Adversaries or Allies? Occasional Thoughts on the Masham-Astell Exchange.” Eighteenth-Century Thought 1: 123-149.

- Broad, Jacqueline, and Karen Green. 2009. “Mary Astell.” In A history of women’s political thought in Europe, 1400-1700, 265-287. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2009. “Mary Astell on Virtuous Friendship.” Parergon 26(2): 65-86.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2012. “Impressions in the Brain: Malebranche on Women, and Women on Malebranche.” Intellectual History Review 22(3): 373-389.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2014. “Women on Liberty in Early Modern England.” Philosophy Compass 9(2): 112-122.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bryson, Cynthia B. 1998. “Mary Astell: Defender of the ‘Disembodied Mind’.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 13(4): 40-62.

- Choi, Julie. 2010. “Born Free? Mary Astell’s Reflections upon Marriage and Defoe’s Roxana.” British and American Fiction to 1900 17(2): 5.

- Choi, Julie. 2011. “Women, Religion, and Enlightenment: Mary Astell’s Serious Proposal to the Ladies.” Feminist Studies in English Literature 19(1): 5.

- Choi, Julie. 2014. “Mary Astell`s The Christian Religion: Life, Liberty and Happiness as Professed by a Daughter of the Church of England.” Feminist Studies in English Literature 22(1): 5.

- Clarke, Desmond M. 2013. The Equality of the Sexes: Three Feminist Texts of the Seventeenth Century. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Deluna, D. N. 1993. “Mary Astell: England’s First Feminist Literary Critic.” Women’s Studies 22(2): 231-242.

- Detlefsen, Karen. 2016. “Custom, Freedom, and Equality: Mary Astell on Marriage and Women’s Education.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Detlefsen, Karen. Forthcoming. “Cartesianism and its Feminist Promise and Limits: The Case of Mary Astell.” In Mind and Nature in Descartes and Cartesianism, edited by Catherine Wilson & Stephen Gaukroger. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Deveraux, Johanna. 2008. “”Affecting the Shade’: Attribution, Authorship, and Anonymity in An Essay in Defence of the Female Sex.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 27(1): 17-37.

- Deveraux, Johanna. 2009. “A Paradise Within? Mary Astell, Sarah Scott and the Limits of Utopia.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 32(1): 53-67.

- Duran, Jane. 2006. Eight Women Philosophers: Theory, Politics, and Feminism. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Duran, Jane. 2000. “Mary Astell: A Pre-Humean Christian Empiricist and Feminist.” Presenting Women Philosophers. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Duran, Jane. 2014. “Christianity and Women’s Education: Anna Maria van Schurman and Mary Astell.” Philosophy & Theology 26(1): 3.

- Dussinger, John A. 2013. “Mary Astell’s Revisions of Some Reflections upon Marriage (1730).” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 107(1): 49-79.

- Ellenzweig, Sarah. 2003. “The Love of God and the Radical Enlightenment: Mary Astell’s Brush with Spinoza.” Journal of the History of Ideas 64(3): 379-397.

- Glover, Susan Paterson. 2016. “Further Reflections upon Marriage: Mary Astell and Sarah Chapone.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Goldie, Mark. 2007. “Mary Astell and John Locke.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 65-85. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Harol, Corrinne. 2007. “Mary Astell’s Law of the Heart.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 87-98. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Harris, Jocelyn. 2012. “Philosophy and Sexual Politics in Mary Astell and Samuel Richardson.” Intellectual History Review 22(3): 445-463.

- Hartmann, Van C. 1998. “Tory Feminism in Mary Astell’s ‘Bart’lemy Fair’.” The Journal of Narrative Technique 28(3): 243-265.

- Johns, Alessa. 1996. “Mary Astell’s ‘Excited Needles’: Theorizing Feminist Utopia in Seventeenth-Century England.” Utopian Studies 7(1): 60-74.

- Kinnaird, Joan K. 1979. “Mary Astell and the Conservative Contribution to English Feminism.” The Journal of British Studies 19(1): 53-75.

- Kolbrener, William. 2003. “Gendering the Modern: Mary Astell’s Feminist Historiography.” The Eighteenth Century 44(1): 1-24.

- Kolbrener, William. 2007. “Astell’s ‘Design of Friendship’ in Letters and A Serious Proposal, Part I.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 49-64. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Kolbrener, William, and Michael Michelson. 2007. “’Dreading to Engage Her’: The Critical Reception of Mary Astell.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 1-16. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Kolbrener, William, and Michael Michelson, eds. 2007. Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Kolbrener, William. 2014. “Slander, Conversation, and the Making of the Christian Public Sphere in Mary Astell’s ‘A serious proposal to the ladies’ and ‘The Christian religion as profess’d by a daugher of the Church of England’.” Religion and Women in Britain, c. 1660-1760, edited by Sarah Apetrei, 131-143. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Langton, Rae. 2000. “Feminism in Epistemology: Exclusion and Objectification.” In The Cambridge Companion to Feminism in Philosophy, edited by Miranda Fricker and Jennifer Hornsby, 127-145. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lascano, Marcy. 2016. “Mary Astell on the Existence and Nature of God.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Leduc, Guyonne. 2008. “Mary Astell. Theorist of Freedom from Domination.” Études anglaises 61(4): 475.

- Leduc, Guyonne. 2011. “Mary Astell et le féminisme en Angleterre au XVIIe siècle.” Études anglaises64(3): 376.

- Lister, Andrew. 2004. “Marriage and Misogyny: The Place of Mary Astell in the History of Political Thought.” History of Political Thought 25(1): 44-72.

- McCrystal, John. 1993. “Revolting Women: The Use of Revolutionary Discourse in Mary Astell and Mary Wollstonecraft Compared.” History of Political Thought 14(2): 189-203.

- Michelson, Michal. 2007. “’Our Religion and Liberties:’ Mary Astell’s Christian Political Polemics.” In Virtue, Liberty, and Toleration: Political Ideas of European Women, 1400-1800, edited by Jacqueline Broad and Karen Green, 111-122. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Michelson, Michal. 2007. “’Our Religion and Liberties:’ Mary Astell’s Christian Political Polemics.” In Virtue, Liberty, and Toleration: Political Ideas of European Women, 1400-1800, edited by Jacqueline Broad and Karen Green, 123-136. Dordrecht, Springer.

- Moser, Elisabeth Hedrick. 2016. “Mary Astell: Some Reflections upon Trauma.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Myers, Joanne E. 2005. “Projecting Agents: Epistemological Critique and the Rhetoric of Belief in Eighteeth-Century British Projects, Volume One.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago.

- Myers, Joanne E. 2013. “Enthusiastic Improvement: Mary Astell and Damaris Masham on Sociability.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 28(3): 533-550.

- O’Neill, Eileen. 2007. “Mary Astell on the Causation of Sensation.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 145-164. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Penaluna, Regan. 2007. “Women’s Place? Moral Philosophy and Feminist Thought in Astell, Masham, and Cockburn.” Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University.

- Pepper-Smith, Katherine. 1992. “Gender as a Wild Card in Theories of Human Nature: Mary Astell and Mary Wollstonecraft on Education for Women.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto.

- Perry, Ruth. 1984. “Mary Astell’s Response to the Enlightenment.” In Women and the Enlightenment, edited by Margaret M. J. Hunt, Phyllis Mack, and Ruth Perry, 13-40. New York: Institute for Research in History.

- Perry, Ruth. 1985. “Radical doubt and the liberation of women.” Eighteenth Century Studies 18: 472-493.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Perry, Ruth. 1990. “Mary Astell and the Feminist Critique of Possessive Individualism.” Eighteenth Century Studies 234: 44-57.

- Pickard, Claire. 2007. “’Great in Humilitie’: A Consideration of Mary Astell’s Poetry.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 115-126. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Shapiro, Lisa. 2013. “The Outward and Inward Beauty of Early Modern Women.” Revue philosophique de la France et de l’étranger 138: 327-346.

- Smith, Florence M. 1916. Mary Astell. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Smith, Hannah. 2007. “Mary Astell, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies (1694), and the Anglican Reformation of Manners in Late-Seventeenth-Century England.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 31-48. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Smith, Hilda L. 1982. Reason’s Disciples: Seventeenth-Century English Feminists. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Smith, Hilda L. 2007. “’Cry up Liberty’: The Political Context for Mary Astell’s Feminism.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 193-204. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Sowaal, Alice. 2007. “Mary Astell’s Serious Proposal: Mind, Method and Custom.” Philosophy Compass 2(2): 227-243.

- Sowaal, Alice, and Penny Weiss, eds. 2016. Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell. University Park: Penn State University Press.

- Springborg, Patricia. 1995. “Mary Astell (1666-1731), Critic of Locke.” The American Political Science Review 89(3): 621.

- Springborg, Patricia. 1998. “Astell, Masham, and Locke: Religion and Politics.” In Women Writers and the Early Modern British Political Tradition, edited by Hilda Smith, 105-125. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Springborg, Patricia. 2005. Mary Astell: Theorist of Freedom from Domination. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Squadrito, Kathleen M. 1987. “Mary Astell’s Critique of Locke’s View of Thinking Matter.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 25: 433-439.

- Squadrito, Kathleen M. 1991. “Mary Astell.” In The History of Women Philosophers, Volume 3 / Modern Women Philosophers, 1600-1900, edited by Mary Ellen Waithe, 87-100. Boston: Kluwer Academic.

- Stanton, Kamille Stone. 2007. “‘Affliction, The Sincerest Friend’: Mary Astell’s Philosophy of Women’s Superiority through Martyrdom.” Prose Studies 29(1): 104-114.

- Taylor, E. Derek. 2001. “Mary Astell’s Ironic Assault on John Locke’s Theory of Thinking Matter.” Journal of the History of Ideas 62(3): 505-522.

- Stuart, Judith Anderson. 2004. “Constructing Female Communities in Writings by Margaret Cavendish, Mary Astell, Eliza Haywood, and Charlotte Lennox.” Ph.D. dissertation, York University.

- Sutherland, Christine Mason. 2016. “Mary Astell’s Feminism: A Rhetorical Perspective.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Taylor, E. Derek. 2007. “Are You Experienced?: Astell, Locke, and Education.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 181-192. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Titone, Connie. 2007. “Pulling Back the Curtain: Relearning the History of the Philosophy of Education.” Educational Studies 41(2): 128-147.

- Van Sant, Ann Jessie. 2007. “’Tis better that I endure’: Mary Astell’s Exclusion of Equity.” In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 127-144. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Weil, Rachel. 2000. Political Passions: Gender, the Family and Political Argument in England 1680-1714. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Weiss, Penny A. 2004. “Mary Astell: Including Women’s Voices in Political Theory.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 19(3): 63-84.

- Weiss, Penny. 2016. “’From the Throne to Every Private Family’: Mary Astell as Analyst of Power.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Weiss, Penny. 2016. “Locations and Legacies: Reading Mary Astell and Re-Reading the Canon.” In Feminist Interpretations of Mary Astell, edited by Alice Sowaal and Penny A. Weiss. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Wilson, Catherine. 2004. “Love of God and Love of Creatures: The Masham-Astell Debate.” History of Philosophy Quarterly 21(3): 281-298.

- Zook, Melinda. 2007. “Religious Nonconformity and the Problem of Dissent in the Works of Aphra Behn and Mary Astell. In Mary Astell: Reason, Gender, Faith, edited by William Kolbrener and Michael Michelson, 99-114. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

4. Philosophy & Teaching

This section is forthcoming. Our team is working with the Advisory Board on materials interpreting Astell’s philosophical work and accompanying teaching materials. In the meantime, please see the Teaching section of the website for sample syllabi.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5. Correspondence

Unfortunately, few of Mary Astell’s letters are known to be extant today. Thanks to the publication of Letters Concerning the Love of God, we have access to the philosophical discourse between Astell and John Norris. Much of the correspondence between Astell and Lady Ann Coventry is also extant, as is her exchange with Bishop Hickes. Several other letters from Mary Astell were preserved in the archives of well-known men, including Sir Hans Sloane and John Walker. Ruth Perry’s The Celebrated Mary Astell contains a presentation of this correspondence in an appendix.

References

- Apetrei, Sarah. 2008. “‘Call No Man Master Upon Earth’: Mary Astell’s Tory Feminism and an Unknown Correspondence.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 41(4): 507-523.

- Broad, Jacqueline. 2015. The Philosophy of Mary Astell: An Early Modern Theory of Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Spreadsheet version of table: Excel file (35KB).

| Correspondent | Date | Content | |

| Archbishop Sancroft | 1688? | Undated, unsigned, and written in what appears to be Astell’s handwriting, this letter appeals to Sancroft to help financially support its young author in London | |

| John Norris of Bemerton | 21 September 1693 | Astell’s letter initiating her 1693-94 correspondence with Norris, a well-known Cambridge Platonist. | |

| Unknown lady (see §5.2.1 for breakdown) | 1705 | Part of the Hickes-Astell Controversy discussed in Apetrei 2008 | |

| George Hickes (see §5.2.1 for breakdown) | 1705 | Part of the Hickes-Astell Controversy discussed in Apetrei 2008 | |

| Vicar of Newcastle, N. Ellison | 30 March 1705 | The vicar’s response to Astell’s request for information about the possible mistreatment of Anglican clergy (for John Walker) survives; Astell’s letter apparently does not. | |

| Henry Dodwell | 11 March 1706 | Astell expresses her admiration for Dodwell’s nonjuror status, then goes on to question the point at the heart of his book Case in View. | |

| John Walker | 22 August 1706 | Excerpts from manuscript of biography of John Squire, vicar of the Parish of St Leonards Shoreditch in Middlesex County for Walker’s history of the mistreatment of the High Church. | |

| Mr. Holiday of the SPCK | 11 June 1712 | Report detailing the funding and administrative structure of Astell’s Chelsea school. | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | June or July 1714 (acc. To Perry) | Discusses Elstob and payment for a manuscript | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. | Discussion of the Duchess of Ormonde’s health and Astell’s work | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 16 July 1714 | Discusses why Astell did not bring Coventry flowers as well as Mr. Steele’s book and the love of God | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 26 July 1714 | ||

| Lady Ann Coventry | 10 December 1714 | Brief discussion of the nature of love as the state of wishing and working towards someone’s perfection | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. | Astell’s health | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 12 January 1715 | Affectionate note | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. | Affection note referencing Coventry’s patronage of Astell | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. 12 April | Friendly note regarding call of Lady Jekyll | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 29 August 1715 | Friendly note in which Astell makes excuses for not having responded to Coventry’s last two letters until the present tract; there is also mention of the Duchess of Ormonde’s health | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 10 November 1715 | Friendly note and discussion of unnamed lady at Chelsea who wishes to call on Lady Ann Coventry | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 4 September 1716 | A note expressing Astell’s condolences for the loss of some young person close to Lady Coventry | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 20 June 1717 | Note wishing Lady Coventry a pleasant stay at Titchfield; mention of the Indian Paper | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 1 July 1717 | Friendly note regarding Astell’s appreciation of Lady Coventry’s friendship and lifestyle | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. | Letter expressing Astell’s desire to see or speak to Lady Coventry soon | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 7 June 1718 | Letter discussing the political state of London | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 19 July 1718 | Letter acknowledging the receipt of a letter from Lady Coventry | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 5 August 1718(?) | Letter discussing Astell’s health, the Duchess Ormond, and Astell’s wish for the grave | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 9 September 1718 | Letter discussing health | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. | Note about Lady Coventry’s improving health | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 6 December 1718 | Note about health and mutual acquaintances | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 6 January 1719 | Note updating Lady Coventry on the health of mutual friends | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 10 April 1719 | Note discussing Astell’s health, Halley’s comet, and Norris’s plan to depart from the university | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 11 May 1719(?) | Note about health, mentioning a charity sermon for poor Chelsea girls (perhaps related to Astell’s school?) | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 27 October 1719 | Letter that mentions the progress of Astell’s Chelsea school | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 8 January 1720(?) | Letter discussing Astell’s opinion of the letters of Fénelon. According to Perry, this implies that Astell had mastered French by this time (though she could not read Malebranche in the original when Norris recommended him to her). | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 25 February 1720(?) | Friendly note updating Lady Coventry on the health of Astell and other acquaintances. | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 26 March 1720 | Letter discussing economic affairs (speculation?) as well as the Chelsea school; Astell seems to have asked Lady Coventry to be a trustee. | |

| Sir Hans Sloane | 2 July 1720 | Note sent to Sir Hans Sloane about the disputed use of land for the future Chelsea school site | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 12 August 1720 | Another letter discussing money and Astell’s financial situation. | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. (21 September) | In this letter, Astell mentions that she has not heard from Lady Coventry in some time, and questions whether she (Astell) has done anything to offend her dear friend. | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. | Friendly note | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 24 October 1721 | Friendly note | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 24 November 1722 | Note containing some discussion of politics and mentions of health of acquaintances | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 7 March 1723 | Letter discussing trials and political concerns going on at the time | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | 6 July 1723 | Note discussing Astell’s health and the death of Mrs. Methuen. | |

| Sir Hans Sloane | 25 April 1724 | Friendly note requesting an opportunity to visit Sir Sloane’s archive with Lord Huntington and his sisters | |

| Lady Ann Coventry | n.d. | Note inquiring after Lady Coventry’s health. | |

| Lady Betty Hastings | 4 September 1730 | Letter stating the terms of Lady Hastings’s donation to the Chelsea school. | |

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5.1 Astell-Coventry correspondence

The bulk of Astell’s known extant letters belong to this correspondence between Astell and one of her close friends, Lady Ann Coventry. The letters contain personal details about health, updates on the wellbeing of mutual friends, discussions of current events, and on Astell’s part, philosophical reflections on such topics as her eagerness for death. Astell’s sentimental language and repeated allusions to friendship throughout the letters help to reveal her commitment to these relationships.

References

- Perry, Ruth. 1986. The Celebrated Mary Astell: An Early English Feminist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Spreadsheet overview: Excel file (38KB).

| Date | Content |

| June or July 1714 (according to Perry) | Discusses Elstob and payment for a manuscript |

| n.d. | Discussion of the Duchess of Ormonde’s health and Astell’s work |

| 16 July 1714 | Discusses why Astell did not bring Coventry flowers, as well as Mr. Steele’s book and the love of God |

| 26 July 1714 | |

| 10 December 1714 | Brief discussion of the nature of love as the state of wishing and working towards someone’s perfection |

| n.d. | Astell’s health |

| 12 January 1715 | Affectionate note |

| n.d. | Affectionate note referencing Coventry’s patronage of Astell |

| n.d. 12 April | Friendly note regarding call of Lady Jekyll |

| 29 August 1715 | Friendly note in which Astell makes excuses for not having responded to Coventry’s last two letters until the present tract; there is also mention of the Duchess of Ormonde’s health |

| 10 November 1715 | Friendly note and discussion of unnamed lady at Chelsea who wishes to call on Lady Ann Coventry |

| 4 September 1716 | Appears to be a note expressing Astell’s condolences for the loss of some young person close to Lady Coventry |

| 20 June 1717 | Note wishing Lady Coventry a pleasant stay at Titchfield; mention of the Indian Paper |

| 1 July 1717 | Friendly note regarding Astell’s appreciation of Lady Coventry’s friendship and lifestyle |

| n.d. | Letter expressing Astell’s desire to see or speak to Lady Coventry soon |

| 7 June 1718 | Letter mentioning the political state of London. |

| 19 July 1718 | Letter acknowledging the receipt of a letter from Lady Coventry |

| 5 August 1718(?) | Letter discussing Astell’s health, the Duchess Ormond, and Astell’s wish for the grave |

| 9 September 1718 | Letter discussing health. |

| n.d. | Note about Lady Coventry’s improving health |

| 6 December 1718 | Note about health and mutual acquaintances |

| 6 January 1719 | Note updating Lady Coventry on the health of mutual friends |

| 10 April 1719 | Note discussing Astell’s health, Halley’s comet, and Norris’s plan to leave the university |

| 11 May 1719(?) | Note about health, mentioning a charity sermon for poor Chelsea girls (related to Astell’s school?) |

| 27 October 1719 | Letter that mentions the progress of Astell’s Chelsea school |

| 8 January 1720(?) | Letter discussing Astell’s opinion of the letters of Fénelon. According to Perry, this implies that Astell had mastered French by this time (though she could not read Malebranche in the original when Norris recommended him to her). |

| 25 February 1720(?) | Friendly note updating Lady Coventry on the health of Astell and other acquaintances |

| 26 March 1720 | Letter discussing economic affairs (speculation?) as well as the Chelsea school; Astell seems to have asked Lady Coventry to be a trustee. |

| 12 August 1720 | Letter discussing money and Astell’s financial situation |

| n.d. (21 September) | In this letter, Astell mentions that she has not heard from Lady Coventry in some time, and questions whether she (Astell) has done anything to offend her dear friend. |

| n.d. | Friendly note |

| 24 October 1721 | Friendly note |

| 24 November 1722 | Note containing some discussion of politics and mentions of health of acquaintances |

| 7 March 1723 | Letter discussing trials and political concerns going on at the time |

| 6 July 1723 | Note discussing Astell’s health and the death of Mrs. Methuen |

| n.d. | Note inquiring after Lady Coventry’s health |

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5.2 Astell-Hickes correspondence & Correspondence with an unknown lady