Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, la Marquise Du Châtelet

“Let us reflect a bit why, at no time in the course of so many centuries, a good tragedy, a good poem, a respected tale, a beautiful painting, a good book of physics has ever come from the hand of a woman.”

– Preface to her translation of Mandeville’s “Fable of the Bees” (Project Vox translation)

Émilie Du Châtelet was a French philosophe, author and translator active from the early 1730s until her untimely death in 1749. In addition to producing famous translations of works by authors such as Bernard Mandeville and Isaac Newton, Du Châtelet wrote a number of significant philosophical essays, letters and books. Her magnum opus, Institutions de Physique (Paris, 1740, first edition), or Foundations of Physics, circulated widely, generated heated debates, and was republished and translated into several other languages within two years of its original publication. She participated in the famous vis viva debate, concerning the best way to measure the force of a body and the best means of thinking about conservation principles. Her ideas were heavily represented in the most famous text of the French Enlightenment, the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert, first published shortly after Du Châtelet’s death. Numerous biographies, books and plays have been written about her life and work in the two centuries since her death. In the early 21st century, her life and ideas have generated renewed interest.

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Émilie Du Châtelet was a French philosophe, author and translator who was active from the early 1730s until her tragic death in 1749 (she died six days after giving birth in her early 40s). Because of her well-known collaborations with Voltaire, which spanned much of her adult life, for generations Du Châtelet has been viewed primarily as a handmaiden to her much better known intellectual companion. Her accomplishments and achievements have often been subsumed under his, and as a result, even today she is often mentioned only within the context of Voltaire’s life and work during the period of the early French Enlightenment. Since they spent a number of years together at her chateau in Cirey hosting famous mathematicians, authors and philosophers from throughout Europe, there are many important events during this period that involve Du Châtelet’s joint work with Voltaire.

In recent years, however, the reception of Du Châtelet has been transformed. Far from being viewed as a mere appendage to the more famous work of Voltaire, scholars have begun to recognize the profound importance of Du Châtelet’s own philosophical works. One aspect of this transformation involves a potentially surprising feature of this period in intellectual and philosophical history. It might seem reasonable to assume that Du Châtelet’s own work has always been largely neglected in favor of the work of the more famous Voltaire. After all, Voltaire was arguably the most famous author in all of France, and one of the most celebrated in all of Europe, during various times in his long life. In this respect, Du Châtelet isn’t alone: the number of readers who have encountered Candide, for instance, is orders of magnitude greater than the number who have encountered Leibniz, whose ideas that play famously lampoons. It might also seem reasonable that the various strictures faced by intellectual women like Du Châtelet in early Enlightenment Europe would have prevented her from having a significant impact on the philosophical conversation in her day. But this assumption, however reasonable it might seem, is false. In fact, scholars have recently shown that Du Châtelet’s work had a very significant influence on the philosophical and scientific conversations of the 1730s and 1740s. She was famous. Her works were published and republished in Paris, London, and Amsterdam; they were translated into German and Italian; and, they were discussed in the most important learned journals of the era, including the Memoirs des Trévoux , the Journal des Sçavans , and others. Perhaps most intriguingly, many of her ideas were represented in various sections of theEncyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert (this is an active area of current scholarly research).

This raises a conundrum: if Du Châtelet was famous during her lifetime, why was she considered little more than an assistant of Voltaire’s in later years, after her death? This question is one of the driving topics for future research on Du Châtelet and her legacy. To answer it, many related questions about the creation of the philosophical canon in the late 19th and early 20th centuries must also be raised and answered.

Unlike Voltaire, who famously served as a promoter of Newtonian ideas in France — with his texts from the 1730s, Philosophical Letters and Elements of the Philosophy of Newton — Du Châtelet sought to articulate a general philosophical system, one that would include the best ideas not only of the Newtonians in England and elsewhere, but also of the newly important Leibnizian movement centered in German-speaking Europe. Châtelet’s magum opus, the Institutions de Physique (Paris, 1740, first edition), or Foundations of Physics , presented this general system. It exhibited a detailed familiarity with the ideas of Newton and his followers, but also with Leibniz, Wolff and their new philosophical movement. As every student of eighteenth-century philosophy knows, from at least the time of the extremely popular and influential correspondence between Leibniz and the Newtonian Samuel Clarke (1717, first edition), philosophers and scholars viewed the ideas of the two discoverers of the integral and differential calculus as reflecting fundamentally opposed conceptions of nature and of the methods to be used in understanding it. It is therefore intriguing to note that Du Châtelet began to see past this opposition already in the late 1730s, indicating in her magnum opus that she intended to adopt methods and ideas from each of these camps, attempting to transcend the terms of the debate that separated them. For this reason, some scholars have regarded Du Châtelet as anticipating the philosophical attitude of Immanuel Kant later in the century. The Institutions covered a wide range of philosophical topics, from the basic principles of reasoning and our knowledge of God, to questions concerning the proper views of space, time, matter and the laws of nature. It provides long discussions of the latest research regarding gravity—including presentations of Galileo’s results and of Newton’s more comprehensive work—and insights into the right view of the forces of nature. In this way, the book presents detailed views concerning both topics that would later be considered part of physics, and topics that would later be considered part of metaphysics. Scholars have often suggested that Du Châtelet wished to provide a Leibnizian-inspired metaphysical foundation for a physics that was heavily Newtonian in character, but this interpretation is the subject of some debate.

Du Châtelet also participated in a number of important philosophical disputes in the 1740s. Perhaps the best known is her work within the so-called vis viva debate, concerning the proper methods for measuring the force of a body. This debate was begun with Leibniz’s criticisms of the Cartesian view of body in 1686. After criticizing the Cartesian views of the Secretary of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris, Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan, in 1740, Du Châtelet provoked Mairan into responding to her ideas concerning the forces of bodies. Once he did so, Du Châtelet wrote a rejoinder to his reply, thereby cleverly overcoming the barrier to the inclusion of women in the Academy’s proceedings and publications. Throughout the 1740s, the vis viva debate between Du Châtelet and Mairan was reprinted in various publications in French, translated into Italian and German, and widely discussed by philosophers in various venues. For instance, the debate was picked up and cited by the young Kant in 1747, in his very first publication. There are numerous other examples of the debates and conversations in which Du Châtelet participated.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.2 Portraits

Émilie Du Châtelet was a wealthy, fashionable, aristocratic woman—there are several extant portraits of her. Five of the images on our website are particularly striking in their symbolism.

Portrait after Maurice Quentin de la Tour

The first is the portrait of Du Châtelet displayed on our project’s Home page. The portrait is based on another painting formerly attributed to Maurice Quentin de la Tour, and can now be found in the private collection of the Marquis de Breteuil. Other copies of this painting exist and some appear online, but they may be erroneously identified as the original. For more information on how we identified the correct image, see our Methods page.

According to Patricia Fara (2002), this painting tells a tale of contradictions. On the one hand, at an age when few women received tertiary education and when the field of natural philosophy was almost exclusively reserved for men, Du Châtelet was a gifted philosopher and mathematician and published a major treatise, the Institutions de Physique [Foundations of Physics] under her own name. On the other hand, she lived the life of a wealthy aristocrat, enjoying all the pleasures that the social life of eighteenth-century Paris could offer. She did not shun the social and marital responsibilities appropriate to her sex and rank at the time. Much like Cavendish in the previous century, she was also famous for her energetic personality, love of fashion and gambling, and taste for extravagant costumes and expensive jewelry.

La Tour’s portrait reflects these two sides of her persona. Art historian Mary Sheriff has written that this portrait “enact[s] a struggle between societal expectations and [the sitter’s] own aspirations” (Sheriff 2011, p. 176). At first glance, it communicates that Du Châtelet is a wealthy aristocratic woman: she is “elaborately dressed and coiffed, her ruffles in carefully coordinated colors reflecting the same attention to detail that she devoted to her rooms, where even the dog basket followed her blue and yellow decorative scheme.” (Fara 2002, p. 40). Du Châtelet’s choice of the pastellist La Tour for her portrait supports this interpretation. La Tour was a highly successful portrait painter for the French royalty and aristocracy. His various sitters included Louis XV, Queen Marie Leszczyńska, and the Dauphin. La Tour’s experience as a teacher also reflects his support of women artists. He is known to have trained women like Marie Suzanne Giroust and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard in the art of pastel (Harris and Nochlin 1976, p. 39).

Another possible connection between Du Châtelet and La Tour can be seen through the artist’s work with Voltaire. Voltaire was impressed by La Tour’s expertise and fame, and commissioned a portrait from him in 1735. It is possible that Du Châtelet met La Tour through his prior work for Voltaire. As patrons in eighteenth-century France, upper class women like Du Châtelet possessed real creative authority over their commissioned portraits. These women were aware of the power of visual art to project certain personal, social, and political meanings. They knew how to use portraiture as a way of asserting their cultural and social status (Palmer 2014, p. 245).

Certain attributes of this portrait signal the other, intellectual side of Du Châtelet’s identity. Counter to conventional displays of wealth and femininity, Du Châtelet looks out at the viewer as if she is deep in thought. Her head rests on her hand, a contemplative pose usually reserved for male subjects. She holds dividers (what we would today call a compass), indicating that she’s hard at work at mathematics, traditionally a male discipline. To similar effect, there is an open book in the foreground that shows geometrical manuscripts. And to her right, we see a quadrant, a scientific instrument used to measure a star’s altitude above the horizon.

Du Châtelet’s portrait with her scientific tools not only displays her expertise in mathematics and philosophy, but it also alludes to Du Châtelet’s representation as Urania, the muse of astronomy. The effects of light and shading around Du Châtelet make her appear almost ethereal and strengthen this connection to Urania. In fact, her choice to be depicted as Urania was a tactic employed by other women scientists. Maria Cunitz, a seventeenth-century astronomer, chose to place Urania’s name next to hers on the title page of her Urania propiti (Sheriff 2011, p. 175-176). By associating herself with the muse of astronomy, Du Châtelet connected herself with science and implied her expertise in the subject.

Sheriff has also drawn a compelling comparison between the sitter’s pensive pose and contemporary allegorical images of Study, such as a version painted by Salvator Rosa in the 1640s and currently held at the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, FL. The use of allegory to express their intellect was a recurrent strategy among early modern women. It was a way for them to exhibit virtuous qualities that were not usually associated with their sex. The seventeenth-century Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi, for example, used allegory in her self-portrait currently at Hampton Court. There, Gentileschi portrayed herself at work as an embodiment of her abilities as a painter (Shelley 2011, p. 175).

Portrait by Marianne Loir

The second image also draws attention to Du Châtelet’s dual character as an aristocratic woman and an intellectual. This portrait was painted by Marianne Loir around 1745-1747 and currently resides at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, France (https://musba-bordeaux.opacweb.fr/fr/notice/bx-e-19-portrait-de-gabrielle-emilie-le-tonnelier-de-breteuil-marquise-du-chatelet-8207fec1-8027-40ff-a3c8-82b10123ccbb). It later circulated in print reproductions, such as the one executed by Pierre Gabriel Langlois the Elder in 1786.

Loir’s painting presents Du Châtelet seated elegantly in an ornate chair, perhaps in her reading room or library. She wears a deep blue velvet gown with intricate lace details at the sleeves and a fur-trimmed neckline. In her right hand she holds a compass for doing mathematical calculations, and in her left hand she holds a flower. She makes direct eye contact with the viewer as she gives a slight smile. Her cheeks are heavily made-up with rouge. In the background, one can detect her vast collection of books. To her left, papers and a globe rest on her desk. While this painting portrays Du Châtelet as an intellectual woman of a high social class, it also expresses her femininity unlike any of her other known portraits.

There is evidence to suggest that Du Châtelet commissioned Loir to help the young painter develop her reputation as a professional portraitist. Du Chatelet was a patron of women in the arts and sciences. She was quoted as saying she was “interested in the glory of [her] sex” (Hyde 2021, p. 79). This may have motivated her choice to sit for Loir. By 1747, Loir had only been commissioned for a few other aristocratic portraits and so had yet to establish her reputation as a painter for the high social classes (Loire et al. 2021, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000051582). By contrast, in 1747 Du Châtelet had already published multiple treatises and had a firm career as an intellectual. Early in her career, Du Châtelet had benefitted from the teaching and encouragement of a contemporary mathematician named Marie de Thil. It was after her studies with De Thil that Du Châtelet experienced an intellectual awakening and blossomed into a true student of the sciences, developing a particular passion for Newton and his study of physics (Arianrhod 2012, p. 7). Du Châtelet may have seen a resemblance of herself in Loir. Both Du Chatelet and Loir worked in male-dominated spheres of philosophy and painting. Given her formative connection to another woman of letters, Du Châtelet perhaps wanted to support the young artist and foster a trans-generational network of women in the arts.

The challenge to balance intellect with femininity is highlighted by multiple features in Loir’s portrait, especially when compared to the one by La Tour. For example, the books and globe are placed in the background of Loir’s portrait. By contrast, in the La Tour these objects are at the forefront. Additionally, in Loir’s portrait, Du Châtelet wears much more makeup, giving off a greater appearance of femininity conventional for the period. Flowers are another prevalent feature of Loir’s portrait that emphasizes her model’s femininity and youthful beauty. We find flowers embroidered on the sitter’s upholstered chair. Du Châtelet also holds a carnation in her left hand. She places it squarely in front of her body, making it immediately noticeable to the viewer. This placement of the flower around her womb may be a symbol of maternity. Du Châtelet simultaneously holds a compass in her other hand. Comparatively, this gesture is toward the bottom of the portrait, small, and difficult to see. Taken together, these two objects allude to her dual character as an intellectual woman. However, the bold visibility of the flower and subtlety of the compass emphasize her femininity over her intellectuality.

Algarotti frontispiece

This frontispiece to Francesco Algarotti’s Il Newtonianismo per le dame, ovvero, dialoghi sopra la luce e i colori [Newtonianism for the ladies, or dialogues in light and colors] was published in Venice in 1737. After visiting Du Châtelet’s chateau in Cirey, Algarotti wrote a commentary that presented Newtonian ideas concerning optics to a wide audience. The work presented five days of conversations in which a chevalier explained the latest scientific developments to a lady. The clear implication amongst Du Châtelet’s circle was that Algarotti had claimed to have explained Newtonianism to her. This interpretation was strongly reinforced by the striking resemblance between Du Châtelet and the woman depicted in the frontispiece to Algarotti’s treatise. There, a woman stands at the center of the composition, looking out at the viewer. She poses contentedly as the male figure explains something to her, his thumb and index finger pressed together as he makes a point. For her own part, when Du Châtelet published her magnum opus just three years later, it was neither a commentary nor a popular work, but rather a philosophical treatise.

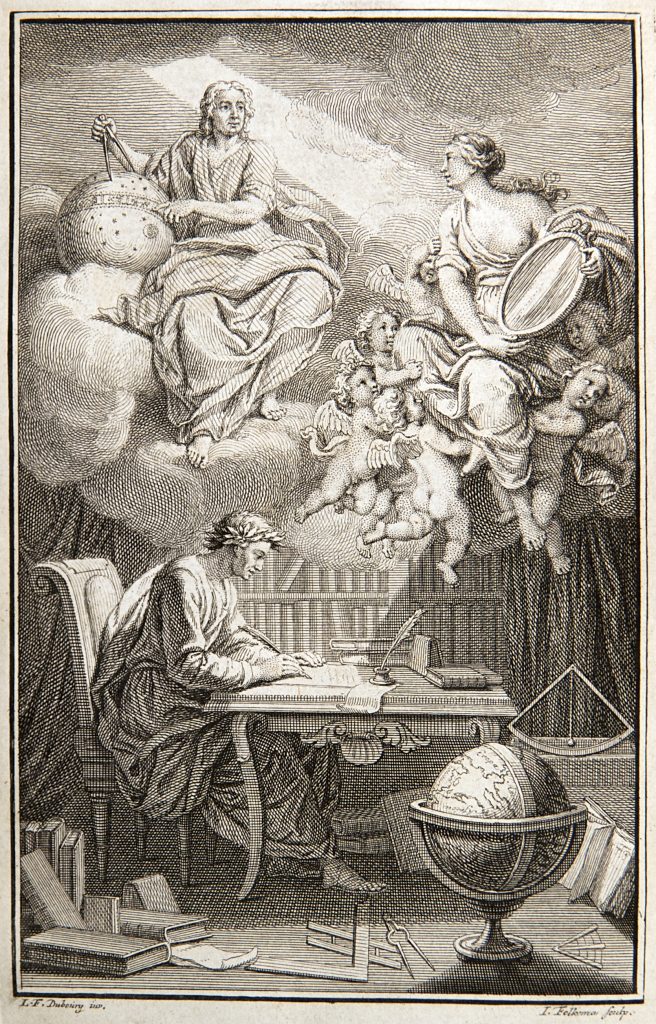

Voltaire frontispiece

This frontispiece to Voltaire’s Élemens de la Philosophie de Newton (1738) was engraved by Jacob Folkema after Louis-Fabricius Dubourg. Appearing in Amsterdam in March of 1738, this edition was not published under Voltaire’s control and lacked some of the material he intended for the work (Voltaire 1992, p. 169-170). The engraving is packed with symbolism, as were many frontispieces at the time: they provided a powerful visual summary of the key arguments of a work. The Élemens identifies Voltaire as the only author, but the engraving tells a different story. Voltaire sits at his desk dressed in an ancient Roman toga with a poet’s laurel wreath on his head. Above him, on the left, is the divine Newton, who sits atop a cloud and gazes down at a light ray emanating from the heavens. The ray of light shines down upon a mirror held aloft by Madame Du Châtelet, who reflects it down upon the page upon which Voltaire is writing at his desk. Other intellectual symbols in the picture include books on the floor, a library in the background, mathematical instruments such as dividers and set squares (which were symbolic of natural philosophy and Freemasonry), and a pendulum and globe in the foreground.

What story does the picture tell? A prominent interpretation is that the engraving symbolizes two conflicting elements. First, it represents the intellectual debt that Voltaire owed to Du Châtelet. Many scholars argue that there is strong evidence that Du Châtelet explained Newtonian science to Voltaire. Voltaire’s forward to the Élemens supports this interpretation: “The solid study that you have made of several new truths and the fruit of considerable work, are what I am offering to the Public for your glory.” Yet the image portrays Du Châtelet as merely reflecting the light of Newton’s ideas down to Voltaire, rather than playing the role of a philosophe on her own. It is especially significant that this frontispiece appeared just two years before Du Châtelet published her own major philosophical treatise.

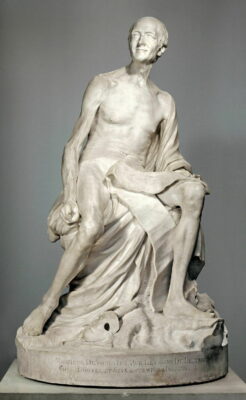

Drawing by Saint-Aubin

Our final image is a drawing done by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin in 1770. It depicts a portrait statue of Du Châtelet, identifiable by the inscription on its base. Saint-Aubin designed this statue for a never-realized sculpture series of Great Women. In Du Châtelet’s left hand we find a copy of her Institutions de physique published in 1740. In the other, she holds a quill actively poised for writing. The liveliness of her pose matches period descriptions of her vivacious character. It also expresses her enthusiasm as a philosopher. Indeed, this hand gesture is a common attribute of philosopher portraits done at the time. A similar, notable example is the portrait of Denis Diderot painted by Louis-Michel van Loo circa 1767.

As in Du Châtelet’s other portraits, her attire in this drawing matches the persona of an aristocratic woman. She wears a patterned dress with fitted bodice that gives a slender curve to her frame and rhymes with the dainty shape of her feet. Her dress sports frills of chiffon at the neck and lace sleeves that cascade down her sides. We can even detect a timepiece hanging from her waist.

Yet Saint-Aubin’s drawing is unique in how it stages Du Châtelet’s relationship with Voltaire. Du Châtelet looks to the left in the direction of a faintly sketched statue, labelled as Voltaire at its base. His head appears turned to the right, returning Du Châtelet’s look as if in conversation with her or as her mirror reflection. The frontispiece described above ranks Du Châtelet below Voltaire and positions her as a mere reflection or conduit of Newton’s ideas. By contrast, this drawing foregrounds Du Châtelet. Her statue is drawn in dark relief whereas the statue of Voltaire is just lightly outlined in the background. The similar physical size of each statue alludes to the parity of their legacies as philosophes.

Pierre Rosenberg has identified one anecdote that provides a backdrop for the planned statue of Du Châtelet (Rosenberg 2002, p. 70). In 1770, during a dinner at the salon of Suzanne Curchod (known as Madame Necker), a group of philosophes decided to commission a statue in honor of Voltaire. The sculptor Pigalle would later realize this work, currently held at the Louvre. Saint-Aubin, though not present at the meeting, was in Necker’s social circle and likely heard about the group’s plans. His drawing suggests he did not want Voltaire’s lifelong interlocutor to be forgotten. It attests to the close association between the two intellectuals in the cultural imaginary of Enlightenment-era France.

References

Arianrhod, Robyn. 2012. Seduced by Logic: Émilie du Châtelet, Mary Somerville and the Newtonian Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bailey, Colin B. 2007. Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, 1724-1780. Paris: Louvre.

Fara, Patricia. 2002. “Images of Émilie du Châtelet.” Endeavour 26 (2): 39-40.

Garrard, Mary D. 2020. “The Divided Self: Allegorical and Real.” In Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe, 197-226. London: Reaktion Books.

Harris, Ann Sutherland and Linda Nochlin. 1976. “Introduction.” In Women Artists: 1550 – 1950, 13–44. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Hyde, Melissa. 2021. “Ambitions, Modest and Otherwise of Two Parisian Painters: Marie-Anne Loir and Catherine Lusurier.” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 50: 59-97.

“Loir, Marianne.” Benezit Dictionary of Artists. 31. Oxford University Press. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/benezit/view/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.001.0001/acref-9780199773787-e-00111140

Loire, Stéphane, Clare Le Corbeiller, Emma Barker, and Philippe Nusbaumer. “Loir Family.”Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000051582.

“Marianne Loir: Artist Profile.” NMWA, 12 June 2020. https://nmwa.org/art/artists/marianne-loir/.

Palmer, Jennifer. 2014. “The Princess Served by Some Slaves: Making Race Visible Through Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century France.” Gender and History 26, no. 2 (August): 242-62.

Rosenberg, Pierre. 2002. Le Livre des Saint-Aubin. Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux.

Shelley, Marjorie. 2011. “Painting in the Dry Manner: The Flourishing of Pastel in 18th-Century Europe.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 68, no. 4: 4–56.

Sheriff, Mary. 2011. “Seeing Beyond the Norm: Interpreting Gender in the Visual Arts.” In The Question of Gender: Joan W. Scott’s Critical Feminism, edited by Judith Butler and Elizabeth Weed, 161–186. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

—. 2007. “The Naked Truth? The Allegorical Frontispiece and Woman’s Ambition in Eighteenth-Century France.” In Early Modern Visual Allegory: Embodying Meaning, edited by Cristelle Baskins and Lisa Rosenthal, 243-264. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Strobel, Heidi A. 2005. “Royal ‘Matronage’ of Women Artists in the Late-18th Century.” Woman’s Art Journal 26, no. 2: 3–9.

Voltaire. 1992. Eléments de la philosophie de Newton, The Complete Works of Voltaire, vol. 15. Edited by Robert Walters and W.H. Barber. Oxford: The Voltaire Foundation.

Wilson, Jean. 2006. “Queen Elizabeth I as Urania.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 69: 151-73.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.3 Chronology

For biographical details, see: Judith Zinsser. 2006. La Dame d’Esprit: A Biography of the Marquise Du Châtelet, New York: Viking.

|

Year |

Event |

|---|---|

| 1706 | Du Châtelet (neé Gabrielle Émilie le Tonnelier de Breteuil) is born in Paris on December 17th. She is part of one of the highest-ranking aristocratic families in France. She spends her childhood at Hotel Dangeau, no. 12 Place Royal, today called the Place des Vosges, in what is now the Marais neighborhood of Paris. |

| 1725 | Du Châtelet marries Florent-Claude, Marquis Du Châtelet-Lomont, 12 June, at the cathedral of Notre Dame. A colonel in one of the king’s regiments, the Marquis hails from one of the oldest aristocratic families in Lorraine. |

| 1726 | Birth of first daughter, Gabrielle-Pauline, on June 30th. |

| 1727 | Birth of first son, Florent-Louise, on November 20th. |

| 1733 | Birth of second son, Francois-Victor, on April 11th. |

| 1733 | Du Châtelet is tutored in mathematics by Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, mathematician and member of the Académie Royale de Sciences, Académie Française, and the Royal Society. They begin a life long intellectual friendship. |

| 1734 | In 1734, Voltaire takes up residence at Du Châtelet’s chateau at Cirey, which becomes a famous center of scholarship and a major destination for mathematicians, writers and philosophers from throughout Europe. It is closer to a mini Academy than to the kind of salons women often ran in this historical period. |

| 1734 | Second son François-Victor dies. |

| 1735 | In the autumn of 1735, Francesco Algarotti, a prominent Italian mathematician and scholar, visits Du Châtelet and Voltaire at Cirey for six weeks. |

| 1736 | Voltaire begins work on his Elémens de la Philosophie de Neuton with Du Châtelet’s assistance. |

| 1737 | On 23 August 1737, Du Châtelet anonymously submits her essay on the nature and propagation of fire (Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu) for a prize essay competition at the Académie Royale des Sciences. |

| 1737 | Algarotti publishes his Newtonianismo per le dame (Newtonianism for the ladies) following his stay at Cirey. The work helps to shape Du Châtelet’s future reputation as a mere translator and expositor of Newton’s ideas; its frontispiece depicts her as the recipient of the author’s teachings. |

| 1738 | In March, Voltaire’s work Elémens de la Philosophie de Neuton is published in Amsterdam: incomplete, without authorization from Voltaire or the French Royal censor, and with the incorrect subtitle Mis a la portée de tout le monde (the work was reprinted in Amsterdam in April with permission). It contains a frontispiece that was not included in other editions published this same year; it depicts Du Châtelet holding a mirror to reflect the light from Newton down to the author Voltaire, contributing to her reputation as an expositor of Newton, rather than a philosophe. |

| 1739 | Du Châtelet does not win the 1738 essay prize for her Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu, but her work is published anonymously by the Académie in a volume with five other submissions. Her entry is also anonymously noted in the Journal de Trévoux and publicly reviewed in Desfontaines’s Observations sur les écrits modernes. |

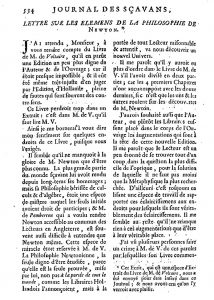

| 1738 | In September, the Journal des sçavans, a prestigious publication specializing in “Philosophy, Science and Arts,” accepts Du Châtelet’s anonymous review of Voltaire’s Elémens. |

| 1739 | In January, the mathematician and natural philosopher Pierre Louise Maupertuis stays at Cirey and begins tutoring Du Châtelet in calculus. |

| 1739 | In May, Du Châtelet relocates to Brussels in order to conduct a legal dispute involving her husband. Samuel König tutors her in mathematics, but their work is cut short due to personal disagreements. |

| 1740 | Du Châtelet anonymously publishes Institutions de Physique in Paris. It is a lengthy philosophical treatise discussing everything from the basic principles of knowledge to the nature of space and time and the understanding of natural phenomena associated with gravity, including the planetary orbits, the pendulum and free fall. |

| 1741 | In February 1741, Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan, the influential secretary of the Académie Royale des Sciences, replies to Du Châtelet’s criticisms of his work on “vis viva” in her Institutions. Du Châtelet publishes his letter and her response in March. De Mairan’s public engagement with Du Châtelet helps to establish her intellectual credibility. |

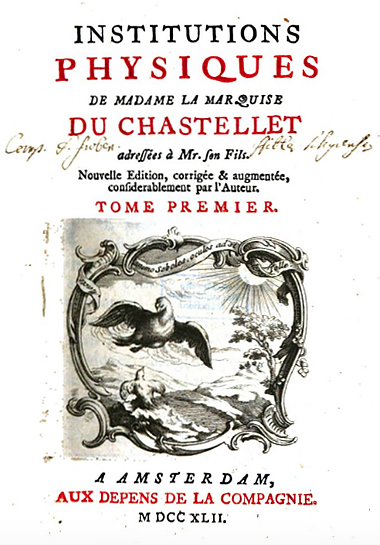

| 1742 | Du Châtelet publishes the second edition of her Institutions; this edition is published under her own name. The edition includes her debate with de Mairan on “vis viva” and an important frontispiece with her portrait. |

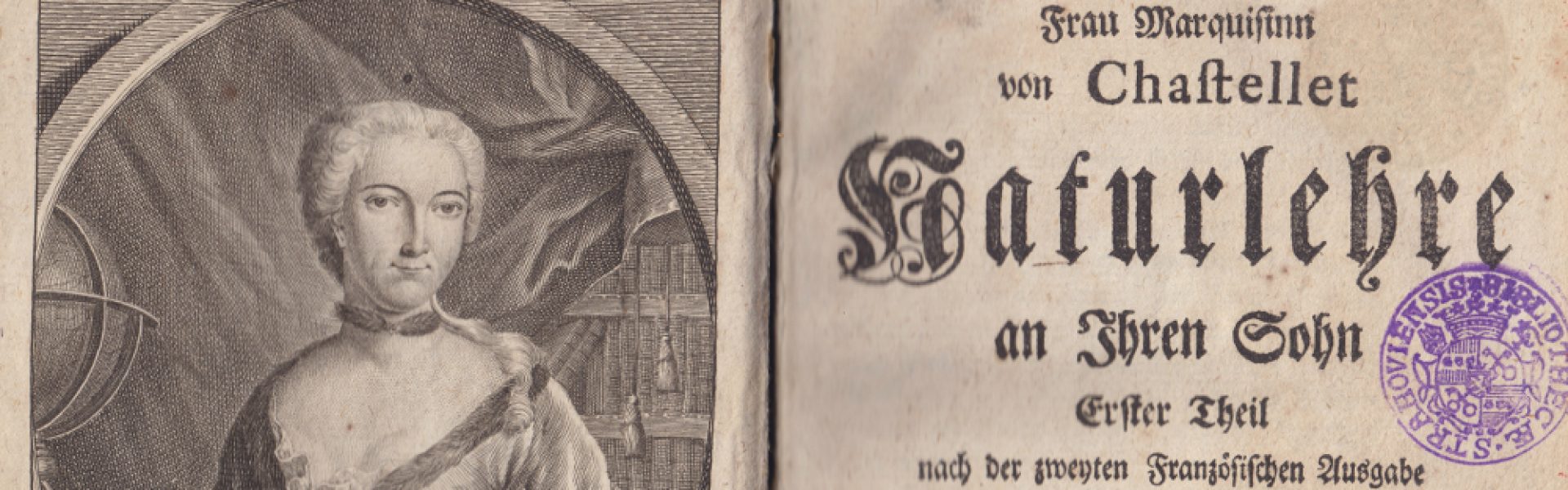

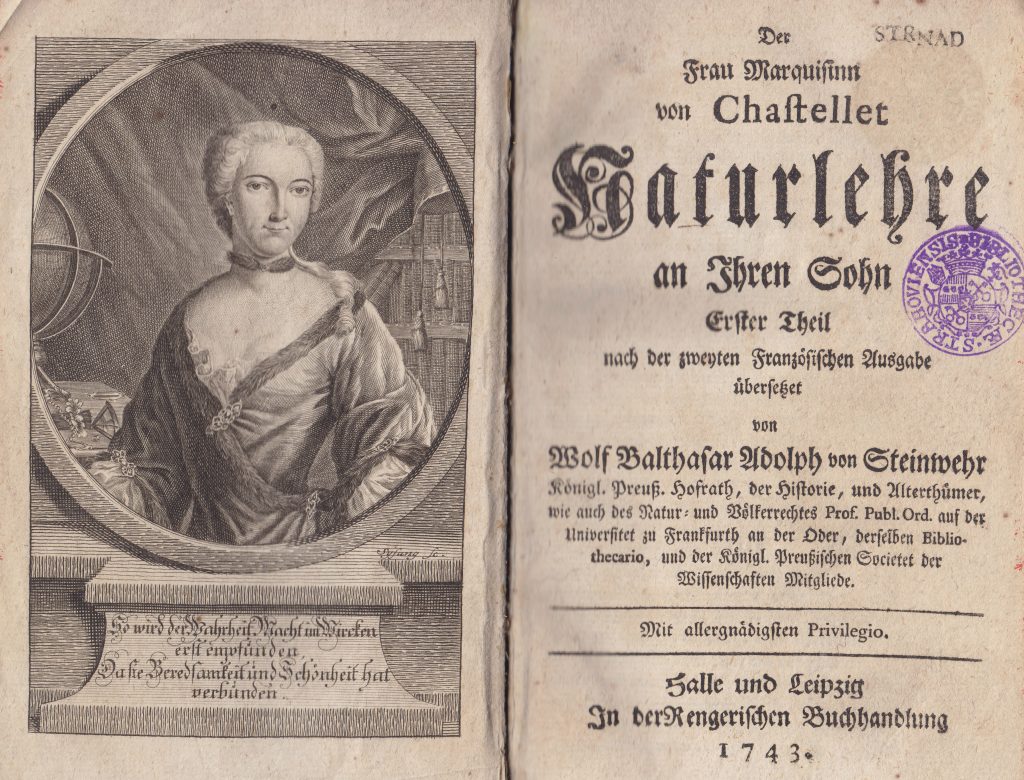

| 1743 | The second edition of the Institutions is fully translated into German and published in Halle and Leipzig. But the title is changed to: Der Frau Marquisinn von Chastellet Naturlehre an ihren Sohn, viz. “the doctrine of nature that the Marquise Du Châtelet gave to her son.” |

| 1743 | The second edition of the Institutions is fully translated into Italian and published in Venice. Père François Jacquier, mathematician and co-editor of the famous Geneva “Jesuit” edition of Newton’s Principia, most likely supervised the translation. The Italian title is closer to the original than the German: Istituzioni di Fisica di Madama la Marchesa du Chastelet Indiritte a suofi Gliuolo, since it retains her phrase “institutions of physics.” |

| 1745 | Du Châtelet is included in the 4th volume of the Bilder-Sal Hautiges Tages Lebender und durch Gelahrheit Beruhmter Schrifft-Steller (Portrait Gallery of Contemporary Authors Famous for their Learning). She was one of four women among a total of one hundred scholars believed to represent the best of Europe’s minds. |

| 1746 | Du Châtelet is elected to the Bologna Academy of Sciences. Laura Bassi, an Italian physicist and one of the first female academics, was also a member of the Academy and lectured at the University of Bologna. Bassi used Du Châtelet’s Institutions in her classes. In the 1750s, Du Châtelet appeared in Italian books as the paragon of a learned woman. |

| 1749 | On the 10th of September, 1749, at the palace of Lunéville in Lorraine, Du Châtelet dies of a pulmonary embolism as a result of complications with the birth of her daughter, Stanislas-Adélaïde. She is buried at the Church of Saint Jacques. A black marble slab without identification marks her burial place today. |

| 1751 | Diderot and D’Alembert, editors of the Encyclopédie, the great symbol of the Enlightenment, credit Du Châtelet in the entry on Newtonianism. Recently, scholars such as Koffi Maglo have identified twelve articles in the Encyclopédiethat copy directly from Du Châtelet’s Institutions. The writer Samuel Formey, author of La belle Wolffian, contributed to many of these articles. |

| 1756 | In 1756, an incomplete edition of Du Châtelet’s translation of, and commentary on, Newton’s Principia appears. In 1759, Alexis-Claude Clairaut, mathematician and friend of Du Châtelet, arranges the full publication of the work. To this day, it remains the only complete French translation of Newton’s magnum opus. |

| 1778 | Voltaire dies in his sleep on May 30, 1778, in Paris. He outlived Du Châtelet by twenty-nine years. Some of her manuscripts were carried along when his extensive personal library was brought to Russia by one of his most important correspondents, Catherine the Great. Those manuscripts remain as part of the Voltaire collection at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg. |

| 1779 | Posthumous publication of Du Châtelet’s Discours sur le Bonheur (Discourse on Happiness). The short text may be her most famous—it appeared in numerous translations and in many editions over the next two centuries. |

2. Primary sources guide

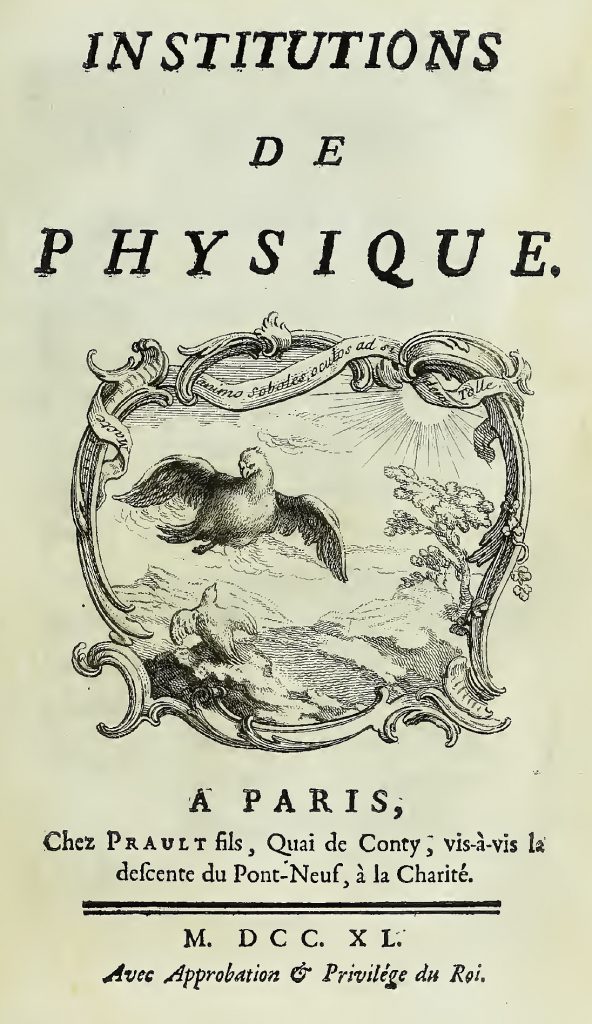

Institutions de Physique

During her relatively short intellectual career — circa 1730-1749— Du Châtelet published a major philosophical treatise, Institutions de Physique (Paris, 1740, first edition). The title is often translated Foundations of Physics, although some scholars argue that it should be translated somewhat more literally as Institutions of Physics. The use of the term “institutions” in French and English was common in this period, reflecting a long tradition in the early modern period of using the Latin equivalent. Obviously, these terms have a somewhat different connotation in contemporary usage. The Institutions was republished in London in 1741, and printed in a second, altered edition in Amsterdam in 1742. By the next year, it had been translated into both German and Italian.

Despite its obvious importance in mid-18th century physics and philosophy, Du Châtelet’s magnum opus has never been reprinted in a contemporary edition, and has never been translated into English. In 2009, the Du Châtelet biographer Judith Zinsser edited and published a partial translation of the text, so it remains the primary source for English readers today. See Zinsser, editor: Du Châtelet, Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings (University of Chicago, 2009).

Contents of Institutions

In the Institutions, Du Châtelet discusses a wide-ranging set of issues in what we would now call philosophy and physics, including such topics as our knowledge of the divine, the principle of sufficient reason, the laws of nature, the nature of motion, and the forces that lead to natural change. The text is famous for discussing ideas that originated with G.W. Leibniz and Christian Wolff, and for using the principle of sufficient reason often associated with their philosophical work. Many of her contemporaries, including the famous materialist La Mettrie, seemed to regard Du Châtelet as the primary interpreter and promoter of Leibnizian philosophical views in France. But her main work is equally famous for providing a detailed discussion and evaluation of ideas that originated with Isaac Newton and his followers. That combination is more remarkable than it might seem now, since the ideas of Leibniz and Newton were regarded as fundamentally opposed to one another by most of the major philosophical figures of the 18th century.

Other works

In addition to the Institutions, Du Châtelet wrote and published a number of other philosophical works. These include an anonymous Dissertation on Fire in 1738, an exchange on vis viva with the Secretary of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris, Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan, and the first modern translation of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica / Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (London, 1687, first edition) — published in Paris in 1756 with a commentary that she co-wrote with the mathematician Alexis Clairaut. The translation remains the standard in French to this day.

Spreadsheet overview of Du Châtelet’s works: Excel file

There is an extensive bibliography on Du Châtelet’s work written by Ana Rodrigues and published in Ruth Hagengruber, editor, Émilie Du Châtelet Between Leibniz and Newton (Dodrecht: Springer, 2012).

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.1 Primary sources — manuscripts

Manuscripts related to Institutions de Physique

Institutions de Physique [1738-1740]. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ffr. 12.265.

Note: The National Library of France has a large bound volume of related manuscript items that concern the editing Châtelet did on drafts of her magnum opus before it was published in 1740. Although the catalogue lists this manuscript as bearing the date of 1738, in reality it contains items from at least 1738 through 1740.

Notes on physics

Nôtes sur la “Physique” par la Même. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 123.

Commentary on, and translation of, Newton’s Principia Mathematica

Principes de la Philosophie Naturelle, par M. Newton, Traduits en Français par Mme la Marquise du Chastellet, avec un Commentaire sur les Propositions qui ont Rapport au Système du Monde. Bibliothèque Nationale: ffr. 12.266–12.268.

Essai sur l’Optique

Essai sur l’Optique. Handschriftenband. Universitätsbibliothek Basel: L I a 755, fo. 230–265.

Note: In 2006, Dr. Fritz Nagel found this copy of the manuscript in Basel. This version contains numerous corrections and additions to the text. Members of the Project Vox team — Bryce Gessell (a PhD student in Duke’s philosophy department) and Andrew Janiak — worked with Nagel to create a transcription of the entire text. In 2019 Gessell published a translation.

Essai sur l’Optique.

Note: Part of the October 2012 sale of Du Châtelet manuscripts by Christie’s; previously held in a private collection, Museé de Manuscrits et des Lettres, Paris; currently under litigation.

Essai sur l’Optique, Chap. IV: de la Formation des Couleurs. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 286.

Discours sur le Bonheur

Discours sur le Bonheur. Mazarine: no. 4.344.

Réflexions sur le Bonheur. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ffr. 15.331.

On Liberty

Essai inédit de Mme du Châtelet, Chap. V: Sur la Liberté. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 126.

Rational Grammar

Chap. VI: Des Mots en Général Considérés selon leurs Signification Grammaticale, Chap. VII: Des Verbes Auxiliaires; Chap. VIII: Des Mots qui Désignent les Opérations de Nôtre Entendement sur les Objets. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 133.

Examinations of the Bible

(Digital scans of select manuscripts below are available courtesy of the Women in Science project at Michigan State University.)

Examen de la Genèse. Manuscripts non autographés. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2376t1.

Examen du livre de Josué. Manuscripts non autographés. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2376t2.

Examen du premier livre des Machabées. Manuscripts non autographés. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2376t3.

Examen des livres du nouveau testament. Manuscripts non autographés. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2377t1.

Examen des actes des apôtres. Manuscripts non autographés. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2377t2.

Examen des actes des apôtres. Manuscripts non autographés. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2377t2.

Preuves…Manuscripts non autographés. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2378.

Brussels National Library, ms. 15188 and 15189.

Translation of The Fable of the Bees.

La Favola delle api, Elena Muceni (ed), Bologna, Marietti, 2020. Available here.

Traduction de la Fable des Abeilles de Mandeville. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 153.

Préface de Cette Traduction. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 217.

Préface de Mad. la Marquise du Chastellet à la Tête de sa Traduction de la Fable des Abeilles, et Dissertation sur Liberté. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, vol. IX: 223.

Traduction de la Fable des Abeilles par Mme du Châtelet. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 240.

Other manuscripts

Recueil de poësies diverses. Tome premier, année 1725 au mois d’avril. Bibliothèque de Troyes: no. 2375.

Lettres Autographés de la Marquise Du Châtelet. Bibliothèque Nationale: ffr. 12.269.

Sur “Descartes” par Mme Du Châtelet. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 122.

Pensées de Madame du Châtelet. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 150.

Lettre de *** à Mad. du Châtelet, 19 Octobre 1747. National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, Voltaire Collection, Vol. IX: 152.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.2 Primary sources — published in Du Châtelet’s lifetime

Lettre sur les Eléments de la Philosophie de Newton

1738. “Lettre sur les Eléments de la Philosophie de Newton.” Journal des Sçavans. September, pp. 534–541 (Paris edition).

1738. “Lettre sur les Eléments de la Philosophie de Newton.” Journal des Sçavans. December, pp. 458–75 (Amsterdam edition).

Gallica link to Paris edition | PDF file

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek link to Amsterdam edition | PDF file

Reply to Voltairomanie

1738. “Reply to the Voltairomanie.” In Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire. Vol. 89. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1969: D. app. 51, 508–12.

Dissertation sur la Nature et la Propagation du Feu

1739. “Dissertation sur la Nature et la Propagation du Feu.” In Recueil des Pièces qui ont Remporté le Prix de l’Académie Royale des Sciences en 1738, edited by Académie Royale des Sciences, pp. 85–168. Paris: Imprimerie Royale.

1744. Dissertation sur la Nature et la Propagation du Feu. Paris: Prault Fils.

Note: Includes Du Châtelet’s epistolary exchange with Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan, the secretary of the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris.

Google Books link original from Lyon Public Library.

Institutions de Physique

1740. Institutions de Physique. Paris: Prault.

Note: This edition was published anonymously, and lacked a frontispiece.

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek link & Google Books link to BSB original

Google Books link to original from Lyon Public Library

1741. Institutions de Physique. Amsterdam: Pierre Mortier.

1741. Institutions de Physique. Amsterdam: Pierre Mortier.

Note: This edition is anonymous.

1741. Institutions de Physique. London: Paul Vaillant.

Note: This edition is anonymous and contains a famous frontispiece depicting Châtelet.

1742. Institutions Physiques de Madame la Marquise du Chastellet Adressés à M. son Fils: Nouvelle Édition, Corrigée et Augmentée Considérablement par l’Auteur. Amsterdam: Aux dépens de la Compagnie.

Note: This second edition differs in various respects from the first; it was published under Châtelet’s name and contains a famous frontispiece depicting Châtelet. The title employs the old spelling of her name.

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek link & Google Books link to BSB original

Note: this is a high-quality, full color scan, with a decent image of the frontispiece. Other scans available online, such as that from the British Library, are inferior.

1743. Der Frau Marquisinn von Chastellet Naturlehre an ihren Sohn. Erster Theilnach der Zweyten Französischen Ausgabe Übersetzet von Wolfgang Balthasar Adolf von Steinwehr Prof. Publ. Ord. auf der Universitet zu Frankfurt an der Oder, Derselben Bibliothekarin, und der Königl. Preußischen Societät der Wissenschaften Mitglied. Halle/Leipzig: Rengerische Buchhandlung.

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek link & Google Books link to BSB original

1743. Istituzioni di Fisica di Madama la Marchesa du Chastelet Indiritte a suofi Gliuolo. Traduzione dal Linguaggio Francese nel Toscano, Accresciuta con la Dissertazione Sopra le Forze Motrizi di M. de Mairan. Venice: Presso Giambatista Pascali.

Note: Includes Du Châtelet’s epistolary exchange with Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan, along with Mairan’s 1728 dissertation on the proper measure of the dead force of bodies, translated into Italian.

Internet Archive link & Google Books link to original from National Central Library of Florence

Exchange with Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan on vis viva

1741. Réponse de Madame la Marquise du Chastellet à la Lettre que M. de Mairan, Secrétaire Perpétuel de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, lui a Écrite le 18 Février 1741 sur la Question des Forces Vives. Bruxelles: Foppens.

Note: Contains only the letter from Châtelet.

HathiTrust link to original from Universidad Complutense de Madrid

1741. Dortous de Mairan, Jean-Jacques. Lettre de M. de Mairan,… à Madame *** [la marquise du Chatelet] sur la question des forces vives, en réponse aux objections qu’elle lui fait sur ce sujet dans ses “Institutions de physique”. Paris: Jombert.

1741. Dortous de Mairan, Jean-Jacques. Lettre de M. de Mairan,… à Madame *** [la marquise du Chatelet] sur la question des forces vives, en réponse aux objections qu’elle lui fait sur ce sujet dans ses “Institutions de physique”. Paris: Jombert.

Note: Contains only the letter from Mairan.

HathiTrust link to original from Universidad Complutense de Madrid

1741. Zwo Schriften, Welche von der Frau Marquise von Chatelet, Gebohrener Baronessinn von Breteuil, und dem Herrn von Mairan, Beständigem Sekretär bei der Französischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, das Maaß der Lebendigen Kräfte Betreffend, Gewechselt Worden: aus dem Französischen Übersetzt von Louise Adelgunde Victoria Gottsched, geb. Kulmus. Leipzig: Bernh. Breitkopf.

Note: German translation of both letters.

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, University and State Library Saxony-Anhalt link

1743. Istituzioni di Fisica di Madama la Marchesa du Chastelet Indiritte a suofi Gliuolo. Traduzione dal Linguaggio Francese nel Toscano, Accresciuta con la Dissertazione Sopra le Forze Motrizi di M. de Mairan. Venice: Presso Giambatista Pascali.

Note: Contains Italian translation of both letters.

Internet Archive link & Google Books link to original from National Central Library of Florence

1744. Dissertation sur la Nature et la Propagation du Feu (Lettre de M. de Mairan … à Madame la Marquise Du Chastellet. Sur la question des Forces Vives, etc.-Réponse de Madame la Marquise Du Chastelet à la lettre que M. de Mairan … lui a écrite … sur la question des forces vives). Paris: Prault Fils.

Note: Contains a reprint of both letters.

Google Books link to original from Lyon Public Library

Letter to J. Jurin

1747. “Mémoire Touchant les Forces Vives Adresseè en Forme de Lettre à M. Jurin par Madame Ureteüil Du Chastellet.” In Memorie Sopra la Fisica e Istoria Naturale di Diversi Valentuomini, edited by Carlantonio Giuliani. Lucca: Benedini. Vol. 3, pp. 75–84.

Note: A work containing texts in Latin, French and Italian; Châtelet’s letter to Jurin is signed from Cirey, 30 May 1744.

Online digitization & download:

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek Digital link

For image sources and permissons see our image gallery.

2.3 Primary sources — published posthumously

The only edition of a number of Du Châtelet’s works in English:

2009. Judith Zinsser, editor; Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser, translators. Emilie Du Châtelet: Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

The edition contains selections from the following works:

- Bernard Mandeville’s The Fable of the Bees

- Dissertation on the Nature and Propagation of Fire

- Foundations of Physics

Note: Contains English translations of selections from the 1740 Paris edition. Selections include Preface, and Chapters 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 11 and 21. Chapter 3 is listed as translated, but is not included in the edition.

- Examinations of the Bible

- Commentary on Newton’s Principia

- Discourse on Happiness

Institutions de Physiques

1806. “De l’existence de Dieu” In Lettres Inédites de Madame la Marquise du Chastelet a M. le Comte d’Argental: Auxquelles on a Joint une Dissertation sur l’Existence de Dieu, edited by Claude Hochet. Paris: Chez Xhrouet.

Note: Includes Dissertation sur l’existence de Dieu (Ch. 2 of Institutions de Physique) and Réflexions sur le Bonnheur.

Google Books link to original from Oxford University Library

1988. Institutions Physiques: Nouvelle Édition. Published as a volume in Christiaan Wolff, Gesammelte Werke, ed. Jean Ecole 28, Abt. 3: Materialien und Dokumente. Hildesheim, Zürich, New York: Olms.

Note: Facsimile reprint of the 1742 Amsterdam edition.

2009. Judith Zinsser, editor; Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser, translators. Emilie Du Châtelet: Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Note: Contains English translations of selections from the 1740 Paris edition. Selections include Preface, and Chapters 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 11 and 21. Chapter 3 is listed as translated, but is not included in the edition. Additional chapters of Institutions de Physiques have been translated by Katherine Brading (Duke University) and other members of the Notre Dame Group, and are available at https://www.kbrading.org/du-chatelet.

Lettre sur les Eléments de la Philosophie de Newton

1968. “Lettre sur les ‘Elements de la Philosophie de Newton’.” In The Complete Works of Voltaire, Vol. 84, edited by Theodore Besterman, pp. TBC. Geneva & Toronto: Institut et Musée Voltaire; University of Toronto Press.

Dissertation sur la Nature et la Propagation du Feu

1752. “Dissertation sur la Nature et la Propagation du Feu.” In Recueil des Pièces qui ont Remporté le Prix de l’Académie Royale des Sciences Depuis leur Fondation jusqu’à Présent, avec les Pièces qui y sont Concouru, Depuis 1738 jusqu’en 1740: Tome Quatrième, Contenant les Pièces Depuis 1738 jusqu’en 1740, edited by Académie Royale des Sciences. Paris: Gabriel Martin, J. B. Coignard, Hippolyte-Louis Guérin, Charles-Antoine Jombert.

Note: Mentions of Du Châtelet and her work appear on pages Pièces contenues (her name), 85 (mention), 87-170 (Dissertation), and 220-221 (her requested changes).

Google Books link to original from National Library of the Czech Republic

Hathi Trust link to original from Universidad Complutense de Madrid

2009. Judith Zinsser, editor; Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser, translators. Emilie Du Châtelet: Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Translation of, and commentary on, Newton’s Principia Mathematica

1756. Isaac Newton; Émilie Du Châtelet, translator. Principes Mathématiques de la Philosophie Naturelle: par Feue Madame la Marquise Du Chastellet. 2 Vols. Paris: Desaint & Saillant.

Note: Incomplete edition.

1759. Isaac Newton; Emilie Du Châtelet, translator. Principes Mathématiques de la Philosophie Naturelle: par Feue Madame la Marquise Du Chastellet. 2 Vols. Paris: Desaint & Saillant.

1759. Isaac Newton; Emilie Du Châtelet, translator. Principes Mathématiques de la Philosophie Naturelle: par Feue Madame la Marquise Du Chastellet. 2 Vols. Paris: Desaint & Saillant.

Note: Complete edition. The second volume includes Du Châtelet’s “Exposition Abrégée du Système du Monde, et Explication des Principaux Phénomènes Astronomiques Tirée des Principes de M. Newton.” See table of contents link below.

HathiTrust link to original from Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Google Books link to Volume 1 from the Lyon Public Library

Google Books link to Volume 2 from the Bavarian State Library

1990. Isaac Newton; Du Châtelet, translator. Principes Mathématiques de la Philosophie Naturelle. Sceaux: Jacques Gabay.

Note: Facsimile reprint.

Gallica links to Volume 1 and Volume 2

2009. Judith Zinsser, editor; Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser, translators. Emilie Du Châtelet: Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Discours (or, Réflexions) sur le Bonheur

1779. “Discours sur le Bonheur.” In Huitième Recueil philosophique et littéraire de la Société Typographique de Bouillon. Tome 8, pp. 1-78. Bouillon: Société Typographique de Bouillon.

1796. “Réflexions sur le Bonheur.” In Opuscules Philosophiques et Littéraires, la Plupart Posthumes ou Inédits, edited by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Suard and Simon-Jérôme de Bourlet Vauxcelles, pp. 1–40. Paris: De l’Imprimerie de Chevet.

1796. “Réflexions sur le Bonheur.” In Opuscules Philosophiques et Littéraires, la Plupart Posthumes ou Inédits, edited by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Suard and Simon-Jérôme de Bourlet Vauxcelles, pp. 1–40. Paris: De l’Imprimerie de Chevet.

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek link & Google Books link to BSB original

Gallica link

1806. “De l’existence de Dieu” In Lettres Inédites de Madame la Marquise du Chastelet a M. le Comte d’Argental: Auxquelles on a Joint une Dissertation sur l’Existence de Dieu, edited by Claude Hochet. Paris: Chez Xhrouet.

Note: Includes Dissertation sur l’existence de Dieu (Ch. 2 of Institutions de Physique) and Les Réflexions sur le Bonnheur.

Google Books link to original from Oxford University Library

1958. Discours sur le Bonheur. Geneva: Institut et Musée Voltaire.

1961. Discours sur le Bonheur: Introduction et Notes de Robert Mauzi. Paris: Les Belles-Lettres.

Note: Critical edition.

1992. Discorso sulla Felicità. Edited and translated by Maria Cristina Leuzzi, with a note by Giuseppe Scaraffia. Palermo: Sellerio.

Note: Italian translation.

1996. Discurso Sobre la Felicidad y Correspondencia. Edited by Isabel Morant Deusa. Madrid: Cátedra Universitat de València, Instituto de la Mujer.

Note: Spanish translation.

1997. Discours sur le Bonheur. Préface d’Elisabeth Badinter. Paris: Edition Payot et Rivages.

1999. Acerca de la Felicidad. Translated by Luis Hernán Rodríguez Felder. Buenos Aires: Imaginador.

Note: Spanish translation.

2009. Judith Zinsser, editor; Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser, translators. Emilie Du Châtelet: Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

2019. Eszter Kovács, translator. “Émilie du Châtelet: A boldogságról.” Magyar Filozófiai Szemle 63, no. 3 (July): 191-208.

Note: Hungarian translation.

Examinations of the Bible

1792. Doutes sur les Religions Révélées Adressées à Voltaire, par Émilie Du Châtelet: Ouvrage Posthume. Paris.

1941. “Examen de la Genèse.” In Voltaire and Madame du Châtelet: An Essay on the Intellectual Activity at Cirey, edited by Ira O. Wade. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

2011. Schwarzbach, Bertram E, ed. Examens de la Bible. Paris: H. Champion.

2009. Judith Zinsser, editor; Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser, translators. Emilie Du Châtelet: Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Essai sur l’Optique

1947. Chapter Four, “De la Formation des Couleurs.” In Studies on Voltaire. With Some Unpublished Papers of Mme. du Châtelet, edited by Ira O. Wade. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Note: Contains only chapter four of the “Essai.” Transcribed from the Voltaire Collection in the National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg.

De la Liberté

1947. “De la liberté.” In Studies on Voltaire. With Some Unpublished Papers of Mme. du Châtelet, edited by Ira O. Wade. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

1989. Critical edition of the Traité de métaphysique and Appendix I. In Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, edited by William H. Barber. Vol. 14. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

Grammaire Raisonnée

1947. “Grammaire Raisonnée.” Portions published in Studies on Voltaire. With Some Unpublished Papers of Mme. du Châtelet, edited by Ira O. Wade. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Translation of Mandeville’s La Fable des Abeilles

1947. “Mme. du Châtelet’s Translation of the Fable of the Bees.” In Studies on Voltaire. With Some Unpublished Papers of Mme. du Châtelet, edited by Ira O. Wade. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

2009. Judith Zinsser, editor; Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser, translators. Emilie Du Châtelet: Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Other works

Trapnell, William H, ed. 2001. Six discours sur les miracles de Notre Sauveur: Deux Traductions Manuscrites de XVIIIe Siecle dont une de Mme Du Chatelet (by Thomas Woolston). Paris: H. Champion.

Note: Zinsser (2009) pg. 25 notes that this includes an adapted translation of Woolston’s Six Discours by Du Châtelet. Manuscript located in the Voltaire Collection, National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg, vol. 9, 122–285.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.4 Primary sources — the Encyclopédie

Encyclopedia entries that include material from Châtelet’s Institutions

Research by Koffi Maglo, Glenn Roe, and others, has shown that at least twelve entries in the Encyclopedia include material from Châtelet’s Institutions. The following six entries include material copied, without attribution, from her work:

- Espace

- Hypothèse

- Mouvement

- Pesanteur

- Repos

- Tem[p]s

Among these, the entry on space (1) includes a final paragraph written by D’Alembert which cites Châtelet, and the entry on gravity (4) is partially copied from her Institutions.

The following six entries include quotations from the Institutions:

- Continu

- Contradiction

- Divisibilité

- Pendule

- Suffisante raison

- Vitesse

As the list indicates, the Encyclopédistes used her Institutions for information on a wide range of topics, and not merely as providing a commentary on Newton’s work.

Reference

2008. Maglo, Koffi. “Mme Du Chatelet, l’Encyclopédie, et la philosophie des sciences.” In Émilie Du Châtelet: eclairages et documents nouveaux. Ferney-Voltaire: Centre International D’Étude Du XVIIIE Siècle.

“Newtonianism” entry

The entry on Newtonianism or the Newtonian Philosophy in Diderot and D’Alembert’s famous Encyclopedia helped to solidify Madame Du Châtelet’s reputation as a commentator on Newton, and as his translator. This is ironic, since the Encyclopedia itself contained at least 12 entries that were copied largely from her magnum opus.

Reference

1765. “Newtonianisme ou Philosophie Newtonienne.” In Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, edited by Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and Denis Diderot. Vol. 11, pp. 122-125. Paris: Briasson.

ARTFL Encyclopédie Project link

Includes links to images of the microfiche version of the original Paris edition produced by IDC (Leiden, The Netherlands). Du Châtelet is mentioned on pg. 123.

English translation

D’Alembert, Jean Le Rond. “Newtonianism or Newtonian Philosophy.” The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Terry Stancliffe. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2015. Originally published as “Newtonianisme, ou Philosophie Newtonienne,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 11:122 (Paris, 1765).

The source of the Michigan translation is the ARTFL Encyclopédie Project. The Editor’s Introductionstates that the Project digitized the first printing of the Paris edition.

Note on editions

There were many editions and contested re-editions of the Encyclopédie in several formats, published in various locations.

Neûchatel re-edition

1777-1780. A Neûchatel: Chez Faulche.

Du Châtelet is mentioned on pg. 123.

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek link to copy 1 and link to copy 2

Geneva re-edition.

1777. A Genève: Chez Pellet.

Article appears in Vol. 22, pp. 947- 952. Du Châtelet is mentioned on pg. 948.

Lausanne and Berne re-edition

1780-1782. A Lausanne et a Berne: Chez les sociétés typographiques.

Article appears in Vol. 22, pp. 413-418. Du Châtelet is mentioned on pg. 414.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.5 Primary sources — reviews by contemporaries

Madame Du Châtelet’s work circulated widely in Europe, reaching audiences in England, France, Holland, Italy, Prussia, Switzerland, and elsewhere. Her magnum opus, Institutions de physique, was published in French, German, and Italian; various French editions were published in Amsterdam, London and Paris. Reviews of her work, and other kinds of engagement with it, appeared in English, French, Italian and German during her lifetime. These reviews may assist students and scholars in determining how important 18th century figures outside of France—such as Johann Bernoulli II, Leonard Euler, Immanuel Kant, and Christian Wolff—first encountered her work. For instance, one possibility is that Kant read about her philosophy in the famous Göttingen journal listed below. He then referred to Chatelet in his very first publication, the Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces, in 1747. With non-canonical figures such as Châtelet, much research on the circulation of their ideas remains to be done.

Spreadsheet overview of reviews below: Excel file

Journal de Trévoux

Also known as Mémoires pour l’Histoire des Sciences & des beaux-Arts or the Mémoires de Trévoux, this was an influential publication printed by the Jesuits on a monthly basis in France (1701-1782). The journal published critical reviews of scholarship.

1739. Journal de Trévoux: ou, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des sciences et des arts. Paris: Chaubert. May, pp. 3134-3135.

Note: Contains notification of Du Châtelet’s and Voltaire’s entries in the 1738 Académie competition on the Nature of Fire.

HathiTrust link to Slatkine facsimile reprint. Geneva, 1968. Vol. 39, pg. 288.

1741. Journal de Trévoux: ou, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des sciences et des arts. Paris: Chaubert. Articles LXVI & LXVII, August, pp. 1381-1402.

Note: Contains discussion of, and excerpts from, Mairan’s letter in reply to Du Châtelet’s criticism of his views in the 1740 edition of her Institutions; and then on pages 1390-1402, we find discussion of, and excerpts from, her retort. This discussion openly notes that the person in question is in fact Du Châtelet, even though her name is not listed on either his reply or on her retort in their official published versions. The 1740 edition of her Institutions was published anonymously.

HathiTrust link to Slatkine facsimile reprint. Geneva, 1968. Vol. 41, pg. 349-354.

1741. Journal de Trévoux: ou, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des sciences et des arts. Paris: Chaubert. Article XLVI, May, pp. 894-927.

Note: The article discusses each chapter of Institutions in the London edition of 1741; it is a very long book review. It begins by praising the anonymous author of this work for the finesse and style of the writing, noting that these are rare qualities. The work is written for her son and it involves an approachable style throughout as a result. It is concerned with the ideas of Descartes and Newton, but it also discusses the ideas of Leibniz, who is still little known in France. The author promises her son (it doesn’t say her!) a “physique” on the model of Rohault, but more complete; it is true that Rohault is not complete. The author deals well with Descartes, noting that just as it is unfair for the Cartesians to regard “attraction” as a mere hypothesis, it is unfair for the Newtonians to regard it as a property of matter. This author believes that hypotheses are necessary in “physique”—they seem to think that she has a subtle view of this issue.

HathiTrust link to Slatkine facsimile reprint. Geneva, 1968, vol. 41, pp. 228-236.

1741. Journal de Trévoux: ou, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des sciences et des arts. June 1741, Paris: Chaubert. Article LVI, June, pp. 1073-1101.

Note: Discusses or reviews Mairan’s Dissertation sur l’estimation et la measur des forces motrices des corps, Paris, 1741. Du Châtelet is explicitly mentioned on page 1100 (and maybe elsewhere).

HathiTrust link to Slatkine facsimile reprint. Geneva, 1968, vol. 41, pp. 271-279.

1746. Journal de Trévoux: ou, Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des sciences et des arts. September 1746. Paris: Chaubert. Article XCI, September, pp. 1848-1850.

HathiTrust link to Slatkine facsimile reprint. Geneva, 1968, vol. 46, pg. 464.

Journal des Sçavans

Later renamed Journal des Savants, this journal was one of the earliest and most influential academic journals published in early modern Europe – it first appeared in 1665 and is still published today. In the 1700s, the journal was published in two editions, in Paris and Amsterdam. The two locations had different pagination and did not always include the same content each month. In addition, it appears that there were two different Paris printings of the journal, with different paginations (research forthcoming).

Importantly, the journal published an extensive two-part review of Du Châtelet’s Institutions de Physique in both its editions. The reviews appeared at different times in the two editions, first in Paris and then in Amsterdam:

| Date | Location | Content |

| December 1740 | Paris | Review part 1 |

| March 1741 | Paris | Review part 2 |

| March 1741 | Amsterdam | Review part 1 |

| May 1741 | Amsterdam | Review part 2 |

Review part 1 – Paris references

1740. Journal des Sçavans. Paris: Chaubert. December: pp. 737-755.

1740. Journal des Sçavans. Paris: Chaubert. December: pp. 2143-2198.

Review part 1 – Amsterdam reference

1741. Journal des Sçavans. Amsterdam: Janssons. Tôme 123 (1), Janvier-Avril. March: pp. 291-331.

Note: There is also a mention of the Institutions in February, on pg. 278.

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek digital link

Review part 2 – Paris references

1741. Journal des Sçavans. Paris: Chaubert. March, pp. 135-153.

1741. Journal des Sçavans. Paris: Chaubert. March: pp. 399-456.

Review part 2 – Amsterdam reference

1741. Journal des Sçavans. Amsterdam: Janssons. Tôme 124 (2), Mai – Aout. May: pg. 65-107.

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek digital link

Göttingische Zeitungen von gelehrten Sachen

The journal is the oldest still published academic journal in German scholarship. It first appeared in 1739 and is published today under the name Göttingischen Gelehrten Anzeigen. The journal published notices and articles discussing Du Châtelet’s essay on fire and her Institutions.

The journal has been digitized by University of Göttingen digital.

1739. Göttingische Zeitungen von gelehrten Sachen. 31 August: pp. 611 & 883-884. Göttingen: Im Verlag der privilegiirten Universitets Buchhandlung.

Note: Discusses the prize essay on fire by the Académie, noting that Euler won the prize, and that there are other essays in the book, including one by a Cartesian—a follower of Malebranche in fact—named P. Lozeran de Fese and another by someone else. Then there are two more essays: the first is by “Marquise du Châtelet,” and the other is by “Herrn Voltaire.” It says that they already discussed her essay on page 611. And on page 611, from 31 August 1739, in the same periodical, it says that the “Marquise du Châtelet” wrote an essay founded on the concepts of Newton, s’Gravesande and Boerhaave.

1741. Göttingische Zeitungen von gelehrten Sachen. 6 April: pg. 233. Göttingen: Im Verlag der privilegiirten Universitets Buchhandlung.

Note: The article notes that “Die Marquise Du Châtelet, eine grosse Liebhaberin der Naturlehre, worinnen sie sonst des Newtons grundlagen gefolgt und einige proben den der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Paris geaussert hat unlangst institutions de physique nach den Leibnizianischen und Wolffianischen grundlehren in 8. heraus gegeben. Da sie eine grosse K[?]onnerin des herrn von Voltaire ist, so scheinet sie dennoch hiedurch von seiner Meinung abzugehen, das Newton ein grosserer Weltweise, als Leibniz gewesen.”

1742. Göttingische Zeitungen von gelehrten Sachen. 29 January: pp. 66-68. Göttingen: Im Verlag der privilegiirten Universitets Buchhandlung.

Note: Discusses the Institutions de Physique, attributing it to Madame Du Châtelet, noting that the society of booksellers in Amsterdam brought out a new edition. But first it notes that Voltaire published an essay in the 72nd part of the Bibliotheque raisonée entitled “Exposition du livre institutions de physique, dans laquelle on examine les idees de Leibnitz.”

Other contemporary reviews

1739. Observations sue les écrits modernes. Paris: Chaubert. Article CCLXIII. July: pp. 169-188.

Note: Pierre Desfontaines’s critical review of Du Châtelet’s essay on fire. HathiTrust is missing a page. The PDF is a scan of the Slatkine reprint held by Duke University Library. Geneva, 1968, vol. 3, pg. 138-143.

Brucker, Johann Jakob. 1745. Bilder-Sal heutiges Tages lebender und durch Gelahrtheit berühmter Schriftsteller. Vol. 4. Augsburg: Hais. [No pagination.]

Note: Du Châtelet was included in the 4th volume of the “Portrait Gallery of Contemporary Authors Famous for their Learning.” She was one of four women among a total of one hundred scholars believed to represent the best of Europe’s savants (intellectuals). The great mathematician Johann Bernoulli acted as the agent for the editor and Voltaire contributed a short account of her life.

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

1746. Le journal universel, ou mémoires pour servir à l’histoire politique civile, ecclésiastique & littéraire du XVIII. siècle. Utrecht: Lobedanius. Tôme X. August: pp. 411-421.

Note: Article on the subject of women scholars. It praises Du Châtelet’s scholarship and her election to the Bologna Academy of Sciences (pp. 417-421).

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek link

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

3. Secondary sources guide

The following reference list focuses on scholarship that is most relevant to philosophy. The list is by no means exhaustive, as Du Châtelet is a very popular figure in many disciplines and the scholarly literature is vast. There has never been a monograph on Du Châtelet written from an analytic philosophy perspective in English, although new scholarship is forthcoming.

An extensive bibliography created by Ana Rodrigues is available in:

Hagengruber, Ruth, ed. 2012. Émilie Du Châtelet: Between Leibniz and Newton. Dordrecht: Springer.

Introductory resources

Some introductory resources for students and instructors who are just starting to explore Du Châtelet’s philosophy are:

Judith Zinsser’s introduction to her edition Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings (2009).

Karen Detlefsen’s article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2014).

Edited collections

Recent edited collections which include essays on various aspects of Du Châtelet’s life and work, including her natural philosophy:

De Gandt, François, ed. 2001. Cirey Dans la Vie Intellectual: La Réception de Newton en France. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

Hagengruber, Ruth, ed. 2012. Émilie Du Châtelet: Between Leibniz and Newton. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kölving, Ulla, and Olivier Courcelle. 2008. Émilie Du Châtelet: Éclairages & Documents Nouveaux. Paris: Publication du Centre International d’Étude du XVIIIe Siècle 21.

O’Neill, Eileen, and Marcy Lascano, eds. 2019. Feminist History of Philosophy: The Recovery and Evaluation of Women’s Philosophical Thought. Dordrecht: Springer.

Zinsser, Judith and Julie Chandler Hayes. 2006. Émilie du Châtelet: Rewriting Enlightenment Philosophy and Science. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

3.1 Secondary sources

Barber, William H. 1967. “Madame Du Châtelet and Leibnizianism: The Genesis of the Institutions de Physique.” In The Age of Enlightenment: Studies Presented to Theodore Besterman. Edinburgh & London: St. Andrews University Press.

Brading, Katherine. 2018. “Émilie Du Châtelet and the problem of bodies.” In Early Modern Women on Metaphysics. Edited by Emily Thomas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 49-71.

Brading, Katherine. 2019. Émilie Du Châtelet and the foundations of physical science. New York: Routledge.

Brunet, Pierre. 1931. L’introduction des Théories de Newton en France au XVIII Siècle. Paris: A. Blanchard.

Cohen, I. Bernard. 1968. “The French Translation of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica 1756, 1759.” Archives Internationales d’Histoire des Sciences, 84–85: 260–290.

Detlefsen, Karen. 2014. “Émilie Du Châtelet.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Detlefsen, Karen. 2019. “Du Châtelet and Descartes on the Role of Hypothesis and Metaphysics in Science.” In Feminist History of Philosophy: the recovery and evaluation of women’s philosophical thought. Edited by Eileen O’Neill and Marcy Lascano. Berlin: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 97-128.

Ehrman, Esther. 1986. Mme Du Châtelet: Scientist, Philosopher and Feminist of the Enlightenment. Leamington Spa: Berg.

Gandt, François de, ed. 2001. Cirey dans la Vie Intellectuel: La Réception de Newton en France. Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century, 2001: 11. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

Gardiner, L. (1984). “Women in Science.” In French Women and the Age of Enlightenment, edited by S. Spencer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Gessell, Bryce. 2019. “‘Mon petit essai’: Émilie du Châtelet’s Essai dur l’optique and her early natural philosophy.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 27: 860–879.

Gorbatov, I. 2007. “From Paris to St. Petersburg: Voltaire’s Library in Russia.” Libraries & the Cultural Record 42: 308-324.

Greenberg, J. 1986. “Mathematical Physics in Eighteenth-Century France.” Isis 77: 59–78.

Guerlac, Henry. 1981. Newton on the Continent. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hagengruber, Ruth, ed. 2012. Émilie Du Châtelet Between Leibniz and Newton>. Dordrecht: Springer.

Hagengruber, Ruth. 2016. “Émilie du Châtelet, 1906–1749: Transformer of Metaphysics and Scientist.” The Mathematical Intelligencer 38: 1–6.

Hagengruber, Ruth and Hartmut Hecht, editors. 2019. Emilie Du Châtelet und die deutsche Aufklärung. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Hankins, T. L. 1965. “Eighteenth-Century Attempts to Solve the Vis Viva Controversy.” Isis 56: 581–592.

Hankins, T. L. 1985. Science and the Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harth, E. 1992. Cartesian Women: Versions and Subversions of Rational Discourse in the Old Regime. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Huaping, Lu-Adler. 2018. “Between Du Châtelet’s Leibniz Exegesis and Kant’s Early Philosophy: A Study of Their Responses to the vis viva Controversy.” History of Philosophy & Logical Analysis 21: 177–194.

Hutton, Sarah. 2004. “Émilie Du Châtelet’s ‘Institutions de Physique’ as a Document in the History of French Newtonianism.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 35: 515 – 531.

Iltis, Carolyn. 1977. “Madame Du Châtelet’s Metaphysics and Mechanics.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 8: 29–48.

Janiak, Andrew. 2018. “Émilie du Châtelet: Physics, Metaphysics and the Case of Gravity.” In Early Modern Women on Metaphysics. Edited by Emily Thomas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 150-168.

Janik, L.G. 1982. “Searching for the Metaphysics of Science: the Structure and Composition of Mme. Du Châtelet’s Institutions de Physique, 1737-1740.” Studies on Voltaire and the 18th Century 201: 85-113.

Jorati, Julia. 2019. “Du Châtelet on Freedom, Self-Motion, and Moral Necessity.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 57: 255–280.

Kolving, Ulla and Olivier Courcelle, eds. 2008. Émilie Du Châtelet: Éclairages et Documents Nouveaux. Ferney-Voltaire: Centre International d’Étude du XVIIIi-ème Siècle.

Kovács, Eszter. 2019. “Émilie Du Châtelet: A boldogságról.” Magyar Filozófiai Szemle 3: 191–208.

Le Ru, Véronique. 2019. Émilie Du Châtelet philosophe. Paris: Classiques Garnier.

O’Neill, Eileen and Marcy Lascano, eds. (Forthcoming). Feminist History of Philosophy: The Recovery and Evaluation of Women’s Philosophical Thought. Springer.

Reichenberger, Andrea. 2016. Émilie du Châtelets Institutions physiques: über die Rolle von Prinzipien und Hypothesen in der Physik. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Reichenberger, Andrea. 2018. “Émilie Du Châtelet’s interpretation of the laws of motion in the light of 18th century mechanics.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 69: 1–11.

Rey, Anne-Lise. 2017. “Agonistic and epistemic pluralisms: a new interpretation of the dispute between Emilie Du Châtelet and Dourtous de Mairan.” Paragraph 40: 43-60.

Rey, Anne-Lise. 2019. “Der streit um die lebendigen Kraäfte in Du Châtelets Institutions de physique: Leibniz, Wolff und König.” In Emilie Du Châtelet und die deutsche Aufklärung. Edited by Ruth Hagengruber and Hartmut Hecht. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Roe, Glenn. 2018. “A Sheep in Wolff’s Clothing: Émilie du Châtelet and the Encyclopédie.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 51: 179–196.

Stan, Marius. 2018. “Emilie du Châtelet’s Metaphysics of Substance.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 56: 477–496.