Anne Conway, Viscountess Conway and Killultagh

“Nature is not simply an organic body like a clock, which has no vital principle of motion in it; but it is a living body which has life and perception, which are much more exalted than a mere mechanism or a mechanical motion.”

– The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy (1690), Chapter 9, Section 2 (trans. Coudert & Corse)

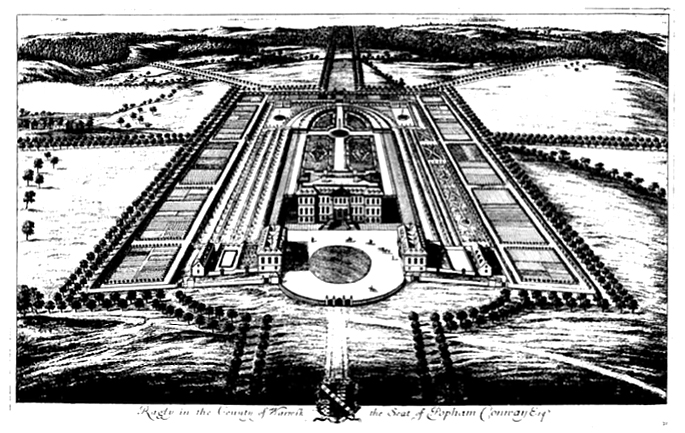

The natural philosophy of Conway is often compared to that of Cavendish, but the two women could not have been more different. Whereas Cavendish courted public attention and fame, Conway preferred to pursue philosophy in the seclusion of her home. Whereas Conway suffered from excruciating headaches all her life, which she bore patiently and without complaint, often in seclusion, Cavendish dressed extravagantly and wrote popular witty poems and plays. Despite Conway’s seclusion, she was mentored and lavishly praised by the philosophers Henry More and Francis Mercury Van Helmont. The German mathematician and philosopher G.W. Leibniz, co-discoverer of the calculus with Isaac Newton, who read Conway’s philosophy only after her death, praised her for her intellectual abilities in his correspondence. Many scholars argue that Leibniz is indebted to her thought, and some have traced his concept of the “monad” to her influence. During a time when women were excluded from university education, Conway so impressed More that he not only become her philosophy mentor, but also a lifelong friend and fervent admirer. She similarly impressed Van Helmont, who spent a decade of his life discussing kabbalistic philosophy with her at her home in Ragley. She learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew in order to pursue her interests in Platonism and the Lurianic Kabbalah, and was an avid reader of Robert Boyle’s experimental work. Her treatise, The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, discusses the philosophy of Descartes, Hobbes, More and Spinoza, and is influenced by the Kabbalah. By all accounts sweet and self-effacing, Conway was also remarkably open minded and independent of spirit in her religious views: shortly before her death, to the consternation of her family and friends, she joined Van Helmont in converting to Quakerism.

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Conway was born as Anne Finch in London, on the 14th of December 1631, into a politically influential family. She was the youngest child of Elizabeth Bennett and Sir Heneage Finch, a former House of Commons speaker, who died before Conway was born. Both her parents had previous marriages, and therefore Conway had a number of half siblings, including her beloved older brother John Finch. Her childhood was spent at what is today known as Kensington Palace, in London. From an early age, Conway suffered from extremely painful headaches, which were to continue for the rest of her life. She became well known for her patient bearing of the illness and for seeking cures from leading physicians and natural philosophers of her time. This included a failed operation by her brother Finch, a cancelled trepanning in Paris, an attempt at healing by the Irish healer Valentine Greatrakes, taking medicine suggested by Robert Boyle, and near poisoning by mercury when Frederick Clodius, son-in-law of Samuel Hartlib, tried to cure her headaches. Her future husband Edward Conway, her brother John Finch, and her intellectual mentors Henry More and Francis Mercury Van Helmont, spared no expense or contact to help her.

There is little information regarding Conway’s early education, although some scholars suggest that her brother John Finch may have tutored her. Later in life she learned Latin and Greek, and also Hebrew, in order to be able to read the Jewish mystic works of the Kabbalah. We can glean from extant correspondence with her father-in-law Lord Conway that by the time she engaged in philosophical correspondence with Henry More in 1650, she was already widely read and interested in philosophy. It is most likely through her brother John that More and Conway came into contact. Finch was a student of Henry More at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he took his MA in 1649. Sometime prior to Finch’s departure for Italy in 1651, Conway commenced a correspondence course in philosophy with More, who initially tutored her in Cartesian philosophy, challenging his bright pupil not with the Meditations, but with Descartes’s Principles of Philosophy, his extensive Latin treatise in natural philosophy. The correspondence eventually turned into a lifelong friendship and mutual admiration, despite the differences in social rank and gender between them.

In February 1650, Anne Finch married Colonel Edward Conway (1623-83), later third Viscount Conway and first Earl of Conway. The newly married couple first lived at Conway’s home in Kensington Palace, and later took up residence at Ragley Hall in Warwickshire, England. They had only one child, Heneage Edward Conway, who was born in 1658 but who died two years later due to smallpox. Conway herself contracted the illness and was somewhat disfigured, but survived. Due to her painful headaches, Conway preferred to pursue her philosophical interests at home and to remain in seclusion at Ragley. She also benefited from one of the largest private libraries in England, with more than 11,000 volumes, collected by her father-in-law the second Viscount Conway (Lord Conway). Her husband Edward does not seem to have had a university education, but Lord Conway was an erudite man and virtuoso, encouraging Conway in her pursuit of philosophy and purchasing books for her. The marriage seems to have been a happy one, with both Edward and Lord Conway showing concern for Conway’s health and education.

Conway’s supportive family included her virtuoso and physician brother John Finch, who obtained a medical degree at the famous University of Padua in 1657. He remained in touch via correspondence, sending Conway presents of philosophical books and even a dog called Julietto from Italy. He became a member and foreign correspondent of the Royal Society in England in 1663, and in 1671 he was appointed ambassador to the court of the Ottoman Empire. Finch’s reports from his travels provided Conway with an important window into other modes of life and thought, including that of Islam, and their correspondence continued with discussions of various philosophical topics.

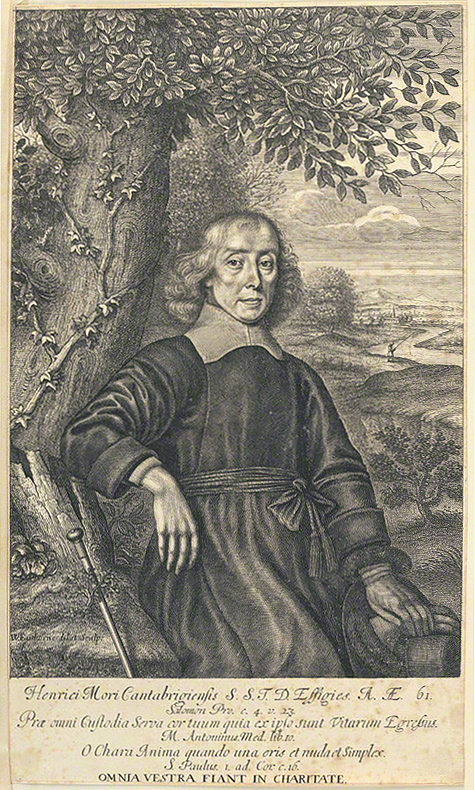

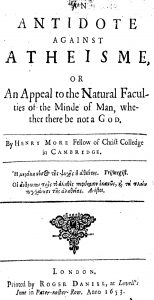

During the 1650s and 1660s, Conway continued her intellectual friendship with Henry More. He dedicated his work Antidote Against Atheism (1653) to Conway, and in 1655 he published Conjectura Cabbalistica at her request. In 1659, he published Of the Immortality of the Soul, which he dedicated to Conway’s husband Edward. They maintained a frequent correspondence on various personal, philosophical and theological issues, including the Kabbalah, religious enthusiasm, and millenarianism. The correspondence does not discuss More’s philosophy directly, but some of Conway’s and More’s views can be gleaned from their theological discussions. In 1656, More accompanied Conway to Paris, where she hoped to have her headaches cured, but the operation was cancelled.

The Conways spared no expense in trying to cure Anne, and a number of eminent physicians and natural philosophers tried to help her. She consulted, for example, the physician and discoverer of blood circulation William Harvey, the Swiss royal physician Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, and the natural philosopher Robert Boyle. Some scholars also argue that there is evidence that John Finch tried to cure his sister by operating on her head in 1665. Most famously, the Conways persuaded the great Irish healer Valentine Greatrakes to attempt to cure Conway in 1666. The attempt proved unsuccessful, but gained much publicity. Physicians, philosophers and virtuosos, such as Lord Conway, Boyle, Ezekiel Foxcroft, and Henry Stubbe, were all interested in his methods, and Greatrakes was invited to perform in front of the Royal Society.

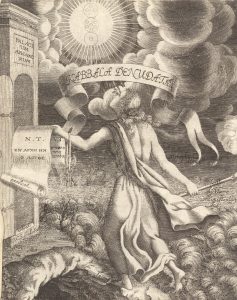

In 1653, Lord Conway and John Finch also tried to engage the renowned physician, natural philosopher, chymist, Christian kabbalist and court diplomat Francis Mercury Van Helmont to cure Conway. They could not reach him at the time, but in 1670 another opportunity presented itself. Van Helmont traveled to England on business for Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia (who is known amongst philosophers for her extensive correspondence with Descartes), and contacted Henry More on behalf of the Christian kabbalist and Hebrew scholar Christian Knorr Van Rosenroth. At the time, Van Rosenroth was working on his magnum opus the Kabbala Denudata, an edited collection based on the writings of the kabbalist mystic Isaac Luria (1534-1572). The work was eventually published in two parts, in 1677 and 1684. It is at More’s behest that Van Helmont finally came to Conway’s assistance. He was not able to cure her, but was so impressed with her that he became her intellectual companion instead, spending the last decade of her life as her guest at Ragley (c. 1670/1 – 1679).

Van Helmont thus became Conway’s second key philosophical mentor. He developed Conway’s interest in the Kabbalah and was instrumental in her conversion with him to Quakerism in 1677. He also played an important role in publishing and disseminating her philosophy after her death.

Van Helmont was deeply influenced by the research of Van Rosenroth into Lurianic Kabbalah, as well as by the Quaker groups that he had encountered at Frederick’s court. Van Helmont introduced Conway and More to Van Rosenroth and had his manuscripts of the Kabbala Denudata sent to More, who then shared them with Conway. He also facilitated Conway’s introduction into Quaker circles. During the mid to late 1670s, Conway met a number of the Quaker leaders, including George Keith in 1675 and Lilias Skene in 1677, and she also corresponded with William Penn, who was unable to meet her in person. According to some scholars, Conway converted for a number of reasons: she identified her own physical suffering with the hardships faced by the group, she found the theological underpinnings attractive, and she identified parallels between Quaker beliefs and the Kabbalah.

Neither Conway’s family nor Henry More were pleased with Conway’s active interest in Quakerism and did not approve of her eventual conversion. Nevertheless, they respected her choice, even if they tried hard to dissuade her. More engaged in philosophical debates with some of the Quaker leaders, such as George Keith, and modified his views towards the Quakers in deference to Conway.

The last ten years of Conway’s life therefore saw active philosophical discussions on the subject of the Kabbalah and Quakerism amongst Conway, More, Van Helmont, and the Quaker leader George Keith. These discussions are documented in the Conway correspondence and other texts by these philosophers. Scholars agree that the discussions had an important influence on Conway’s thought, and it is most likely during the 1670s that she composed the philosophical notes that served as the basis for her main work, the Principles. During this time Van Helmont also published the Latin version of his Cabbalistical Dialogue, which was included in the first volume of the Kabbala Denudatain 1677/8, and subsequently published in English in 1684. According to some scholars, Van Helmont’s works, Adumbration Kabbalae Christianae (1684) and Two Hundred Queries Concerning the Revolution of Human Souls (1684), are indebted to these discussions and perhaps also to Conway.

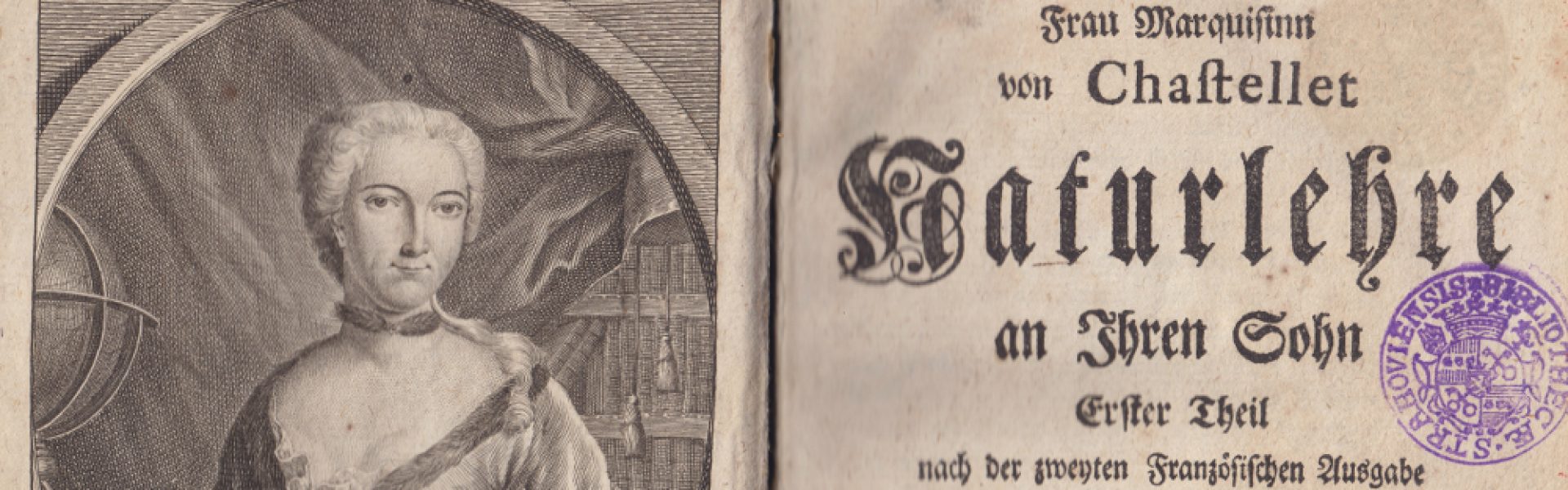

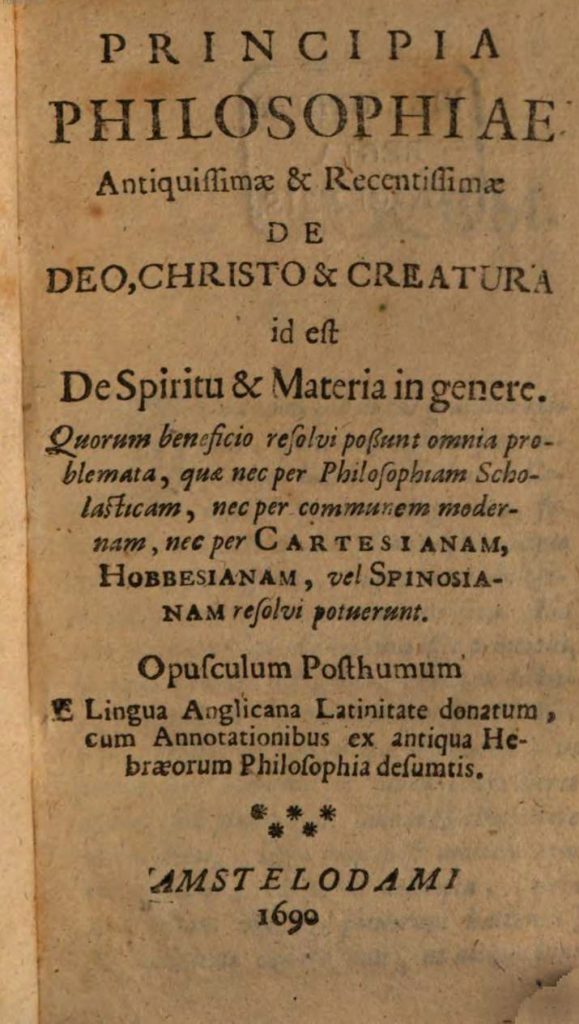

Following a long illness, Conway died at the age of forty-seven in 1679 and was buried with the simple epitaph “A Quaker Lady.” After Conway’s death in 1679, Van Helmont traveled to the Netherlands and published Conway’s notes as her treatise The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. The personal notes are no longer extant, so it is not possible to determine with certainty what changes, if any, he may have made. There is also scholarly debate as to when exactly Conway wrote the text. Some scholars suggest that she wrote her treatise sometime between 1671 and 1675, given the apparent influence of Van Helmont’s ideas and the lack of any reference to the Quakers, whom she became more actively involved with after 1675. The treatise covers numerous topics, including dualism, materialism, the nature of God, and theodicy, and discusses the ideas of More, Descartes, Hobbes and Spinoza. The treatise was first published anonymously in 1690 in Amsterdam, in Latin, as part of a collection of three treatises titled Opuscula Philosophica. One of the treatises was Van Helmont’s Two Hundred Queries. In 1692, the work was published in English in London.

During his stay in Netherlands, Van Helmont also befriended the philosopher John Locke. He then visited Locke and Lady Masham at Oates in 1693, and it is possible that through him Locke and Masham may have become exposed to Conway’s ideas, although no record remains. He also presented a copy of Conway’s Principles to his friend Leibniz, whose annotated copy can still be seen at the Leibniz Archiv at the Niedersachsische Bibliothek in Hannover, Germany.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.2 Portraits

The extant correspondence mentions only one portrait of Conway. Henry More owned the miniature portrait – it is one of the few personal possessions listed in his will. It was at his deathbed at Cambridge, next to that of Descartes. In a letter to Conway from 1 May 1657, More writes: “Next to your Ladyship’s self there is nothing that I do so highly esteem as your picture …” (Nicolson, p. 143). Unfortunately, the portrait seems to have disappeared.

Conway’s brother, John Finch, also commissioned portraits from the Dutch painter Samuel Van Hoogstraten (1627 – 1678), one of which is thought to be of Conway, but this remains a matter of scholarly controversy. The paintings by Van Hoogstraten include a portrait of Finch, a group portrait of Finch’s nephews, and a painting now called “Perspective View with a Woman Reading a Letter.” This painting is now on display at the Prince William V Gallery, at the Mauritshuis Art Museum in The Hague, Netherlands. Some scholars think that this painting, which is included on our website, depicts Conway and that her face is based on More’s miniature portrait of her. This interpretation is based on the idea that the backgrounds in what is thought to be the John Finch portrait and in the “Perspective View” paintings are similar, showing a large pillared hall, a cat and a dog. The dog is taken to be Conway’s pet puppy Julietto, sent to her by her brother John as a present from Italy.

The attribution of the John Finch portrait remains disputed by art historians (see Brusati, 1995, pg. 365, footnote 93.) The painting is called “Perspective Portrait of a Young Man Reading in a Courtyard,” and is now in the private collection of the Christie-Miller family at Clarendon Park, Salisbury, England. A reproduction is available through the Courtauld Institute of Art. Both the Finch and Conway portraits were reprinted in the 1916 October issue of the Burlington Magazine.

Image of John Finch forthcoming.

References

Brusati, Celeste. 1995. Artifice and Illusion: the Art and Writing of Samuel Van Hoogstraten. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cust, Lionel, and Archibald Malloch. 1916. “Potraits by Carlo Dolci and S. Van Hoogstraten.” Burlington Magazine 29 (163): 292-293, 296-297.

Hutton, Sarah. 2004. Anne Conway: a Woman Philosopher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (See pg. 96, and pg. 97, footnote 10.)

McRobert, Jennifer. 2000. “Anne Conway’s Vitalism and Her Critique of Descartes.” International Philosophical Quarterly 40 (1): 21-35. (See pg. 21, footnote 2.)

Nicolson, Marjorie Hope, ed. 1930. Conway Letters: The Correspondence Of Anne, Viscountess Conway, Henry More, And Their Friends, 1642-1684. New Haven, Yale Univ. Press, 1930.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

1.3 Chronology

Sources

Corse, Taylor, and Allison Coudert, eds. 1996. The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (See pg. xxxiv)

Hutton, Sarah. 2004. Anne Conway: a Woman Philosopher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

| Year | Life event |

| 14 December 1631 | Conway born as Anne Finch, the daughter of Sir Heneage Finch and Elizabeth Bennett Cradock. She spends her childhood at Kensington Palace. |

| 1644 | Publication of Descartes’s Latin magnum opus in natural philosophy, Principles of Philosophy. |

| 1648 – 1649 | Henry More corresponds with Descartes, raising a number of objections about his dualism of mind and body and his conception of the divine’s relation to nature. |

| 1650 | Conway begins her correspondence with Henry More. |

| 1651 | Publication of Hobbes’s most famous work, the Leviathan. |

| 11 February 1650 | Anne marries Edward Conway (1623-83), later third Viscount Conway and first Earl of Conway. They take up residence at Ragley Hall in Warwickshire, England. |

| 1651 | John Finch, Conway’s brother, departs for Europe. |

| 1652 | John Finch sends Conway three copies of Descartes’s Principles of Philosophy |

| 1653 | John Finch sends Conway books by Copernicus, a treatise by Fromond, and works by Descartes and Galileo. |

| 1653 | Publication of More’s Antidote Against Atheism, which was dedicated to Conway. |

| 1653 | Conway nearly dies of mercury poisoning when Frederick Clodius, son-in-law of Samuel Hartlib, tries to cure her headaches. |

| 1653 | The Conways unsuccessfully try to contact Francis Mercury Van Helmont for medical treatment. |

| 1655 | Publication of More’s Conjectura cabbalistica, written upon Conway’s request. |

| April 1656 | Conway travels with More to France. |

| 1656 | Publication of More’s Enthusiasmus triumphatus. |

| 1657 | Publication of More’s Opera Omnia (1657-69). |

| 6 February 1658 | Birth of Conway’s only child, Heneage Edward Conway. |

| 1659 | Publication of More’s Of the Immortality of the Soul, dedicated to Conway’s husband. |

| 14 October 1660 | Conway’s son Heneage Edward dies of smallpox at the age of two. Conway herself suffers from smallpox and is disfigured, but survives. |

| 1662 | Publication of More’s A Collection of Several Philosophical Writings. |

| 1663 | John Finch elected Fellow of the Royal Society. |

| 1663 | Publication of Robert Boyle’s Some Considerations Touching the Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy. Conway reads the work and then asks her husband to purchase his other works. |

| 1664 | Conway seeks medical advice from Robert Boyle. |

| 1665 | John Finch appointed English Resident at the court of Florence. |

| 1665 or 1666 | John Finch attempts to operate on Conway’s head. |

| January – February 1666 | Irish healer Valentine Greatrakes tries to heal Conway. |

| 1670 | Publication of Baruch Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. |

| 1671 | Conway sends a gift of books to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. |

| September 1671 | John Finch visits England; this is the last time Conway sees her brother. |

| 1671 – 1681 | John Finch becomes ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. |

| November 1670 | Francis Mercury Van Helmont travels to England on behalf of Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. He becomes a personal physician to Conway and moves to Ragley Hall, where he lives until Conway’s death in 1679. |

| November 1675 | George Fox, George Keith, and other Quakers visit Conway and Van Helmont. Van Helmont begins to attend Quaker meetings more regularly. |

| 1675 | Conway corresponds with the Quaker William Penn. |

| February 1676 | Conway employs Quaker women as servants. |

| 1677 | Publication of the first volume of Kabbala Denudata. |

| 1677 | Conway and Van Helmont become Quakers and Conway adopts the Quaker way of dressing. |

| 17 April / 23 February 1679 | Conway dies at age forty-seven of her long-term illness. She is buried with “Quaker lady” as her only epitaph, in the parish church at Arrow, Warwickshire. |

| 1683 | Earl of Conway, Conway’s husband, dies. |

| 1684 | Anonymous publication of Two Hundred Queries Modestly Propounded Concerning the Doctrine of the Revolution of Human Souls and its Conformity with the Truth of the Christian Religion. |

| 1685 | Van Helmont claims authorship of the Two Hundred Queries. |

| 1690 | Conway’s Principles published in Latin in Amsterdam along with the Two Hundred Queries. |

| 1692 | Conway’s Principles published in English in London, with a translation by “J.C.,” an otherwise unnamed translator. Scholars have since speculated about his identity, arguing that the translator may have been Jacobus Crull or the physician John Clark. |

| 1693 | Van Helmont visits John Locke and Masham at Oates; see the Masham section of the site for details. |

2. Primary sources guide

The Principles

Conway did not publish during her lifetime. Her one treatise, The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, was compiled and published anonymously from her extant personal notes by Francis Mercury Van Helmont, her physician and intellectual companion during the last years of her life, 1671 – 1679. These personal notes are no longer extant, so it is not possible to determine with certainty what changes, if any, may have been made to the notes. Some scholars have suggested that Conway wrote the treatise sometime between 1671 and 1675, given the apparent influence of Van Helmont’s ideas and the lack of references to the Quakers, whom she became actively involved with after 1675.

The treatise covers numerous topics, including dualism, materialism, the nature of God, and theodicy. In it, Conway discusses the ideas of Henry More, Descartes, Hobbes and Spinoza.

The treatise was first published anonymously in 1690 in Amsterdam, in Latin, as part of a collection of three treatises titled Opuscula Philosophica Quibus Continentur Principia Philosophiæ Antiquissimæ & Recentissimæ ac Philosophia Vulgaris Refutata Quibus Subjuncta Sunt CC. Problemata de Revolutione Animarum Humanarum. One of the treatises was Van Helmont’s Two Hundred Queries…Concerning the Doctrine of the Revolution of the Souls (1684).

In 1692, the work was published in English in London, with the title The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy: Concerning God, Christ and the Creature; that is, concerning Spirit and Matter in General. The translator, J.C., states that he made the translation from the Latin edition. The identity of “J.C.” is unclear; some scholars suggest that these were the initials of Jodocus Crull, a Dutch physician who also worked as a translator. Other scholars suggest that the initials stand for John Clarke, an English physician who also translated one of Van Helmont’s works, Seder Olam in 1694.

Unpublished preface

In addition to a short preface, which was published in the treatise, there exists a longer, unpublished preface which was later printed in Richard Ward’s The Life of the Learned and Pious Dr. Henry More(1710), along with a biographical sketch of Conway. The preface is signed by Van Helmont, although scholars disagree on whether it was actually written by Van Helmont himself or by Henry More.

Legacy

There is no evidence of John Locke or Masham reading a copy of the work, but it is possible, given that Van Helmont visited them at Oates in 1693. The philosopher G.W. Leibniz certainly owned a copy of the Latin edition and knew that Conway had written it. His copy, inscribed “La comtesse de Konnouay,” is now at the Niedersachsische Landesbibliothek in Hanover, Germany. There is also evidence that he read and referred to the book and that he respected the author. It is likely that Van Helmont presented Leibniz with the copy, as they had become friends in 1671.

Modern text editions of the work are available in English, Spanish and Polish.

Spreadsheet overview: Excel file

The below digital copies of the Ward texts are courtesy of Duke University and Hathi Trust:

Biographical sketch in Ward: PDF file

Unpublished preface in Ward: PDF file

EndNote library: forthcoming

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

2.1 Primary sources

Manuscripts

Conway, Anne 1690. “Principia Philosophiae Antiquissimæ & Recentissimæ de Deo, Christo & Creatura, id est de Spiritu & Materia in Genere.” In Opuscula Philosophica Quibus Continentur Principia Philosophiæ Antiquissimæ & Recentissimæ ac Philosophia Vulgaris Refutata Quibus Subjuncta Sunt CC. Problemata de Revolutione Animarum Humanarum, pp. 1-144. Amsterdam: Prostant Amstelodami.

Conway, Anne. 1692. The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. (English translation by ‘J.C.’ Medicinae Professor). London: Printed in Latin at Amsterdam by M. Brown, 1690. Reprinted at London, 1692.

Online access

The Latin text of the treatise is available online via Google Books, which provides a scan of the 1690 original from the K.K. Hofbibliothek Osterreichisches Nationalbibliothek.

The English text of the treatise is available online through the following proprietary databases:

Early English Books Online database, Gale Group; this provides the text transcript and images of the 1692 original from the British Library.

Intelex Past Masters online database: contains Anne Conway’s posthumously published Principia Philosophiae in the original Latin and English translation, together with her correspondence with Henry More and others. The text is based on the Latin and English 1692 edition, but page references are included to the modern edition by Peter Loptson (1982).

Unpublished preface to the Principles

Ward, Richard. 1710. The Life of the Learned and Pious Dr. Henry More, Late Fellow of Christ’s College in Cambridge. To Which are Annex’d Divers of his Useful and Excellent Letters. London: Printed and sold by Joseph Downing in Bartholomew Close near West-Smithfield.

Note: Pages 192-203 provide a biographical sketch of Conway, and pages 203-209 reprint the Preface by More / Van Helmont.

The original text of the preface is available publicly online at:

A PDF version of the Duke University text scan from Hathi Trust is available below. The first document contains the biographical sketch, and the other document contains the unpublished preface.

Biographical sketch in Ward: PDF file

Unpublished preface in Ward: PDF file

Modern text editions in English

Atherton, Margaret, ed. 1994. Women Philosophers of the Early Modern Period. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Note: Contains excerpts from the Principles.

Corse, Taylor, and Allison Coudert, eds. 1996. The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Loptson, Peter, ed. 1982. The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Note: Modern reprint of Latin and English texts, with editorial introduction.

_____, ed. 1998. The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. Delmar, NY: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints.

Note: Parallel text reprint.

Modern editions in other languages

Orio de Miguel, Bernardino, ed. 2004. La Filosofiá de Lady Anne Conway, un Proto-Leibniz: “Principia Philosophiae Antiquissimae et Recentissimae“. Valencia: Editorial de la UPV.

Usakiewicz, Joanna, ed. 2002. Zasady Filozofii Najstrszej i Najnowsze. Dotyczace Boga, Chrystusa I Stworzenia Czyli o Duchu I Materii. Krakow: Aureus.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

3. Secondary sources guide

The following section (3.1) represents an attempt to identify a complete list of references pertaining to Conway to date. The scholarly literature is not as vast as for some of the other philosophers on the site, such as Cavendish and Du Châtelet, but recent years have seen a renewed interest in Conway and new work is forthcoming.

Introductory sources

A helpful starting point for students and instructors who are just beginning to explore Conway’s life and philosophy are:

Jacqueline Broad’s chapter on Conway in her work Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century(2002)

Taylor Course’s and Allison Coudert’s introduction to their edition of the Principles (1996)

Sarah Hutton’s intellectual biography Anne Conway: a Woman Philosopher (2004)

Sarah Hutton’s entry on Conway in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2014)

Peter Loptson’s introduction to his edition of the Principles (1982)

Karen Warren’s and Jane Duran’s chapter on Conway and Leibniz in An Unconventional History of Western Philosophy (2009)

3.1 Secondary sources

Reference works & encyclopedia articles

Frankel, Lois. 1991. “Anne Finch, Viscountess Conway.” In A History of Women Philosophers: Modern Women Philosophers, 1600-1900 , Vol. 3, edited by Mary Ellen Waithe. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

______. 1992. “Anne Finch Viscountess Conway.” In Essays on Early Modern Philosophers, edited by Vere Chappel. New York: Garland.

Hutton, Sarah. 1998. “Conway, Anne.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. Craig. London: Routledge.

______. 1999. “Anne Conway.” In The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, edited by Robert Audi, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

______. 2008. Lady Anne Conway. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Link.

Sheridan, Patricia. 2002. “Anne Conway (14 December 1631 – 23 February 1679).” In British Philosophers, 1500-1799, edited by Philip B. Dematteis and Peter S. Fosl. Detroit, MI: Gale.

Secondary sources in philosophy

Alic, Margaret. 1986. “The Rise of the Scientific Lady.” In Hypatia’s Heritage: a History of Women in Science from Antiquity Through the Nineteenth Century, edited by Margaret Alic. Boston: Beacon Press.

Allison, Coudert. 1976. “A Quaker-Kabbalist Controversy: George Fox’s Reaction to Francis Mercury Van Helmont.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 39: 171-189.

Battigelli, Anna. 2004. ” ‘The Furnace of Affliction’: Anne Conway, Henry More, and the Problem of Pain.” In Imagining the Sciences: Expressions of New Knowledge in the ‘Long’ Eighteenth Century, edited by Robert C. Leitz, III and Kevin L. Cope. New York, NY: AMS.

Benfey, Theodor. 1986. “Anne Conway’s Interaction with Science, Politics, Medicine and Quakerism.” Guilford Review 23: 14-23.

Boyle, Deborah. 2006. “Spontaneous and Sexual Generation in Conway’s Principles.” In The Problem of Animal Generation in Early Modern Philosophy, edited by Justin E. H. Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Broad, Jacqueline. 2002. Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Stuart. 1990. “Leibniz and Henry More’s Cabbalistic Circle.” In Henry More (1614-1687): Tercentenary Studies, edited by S. Hutton. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

______. 1997. “F.M. Van Helmont: His Philosophical Connections and the Reception of his Later Cabbalistic Philosophy.” In Studies in Seventeenth-Century European Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Byrne, David. 2007. “Anne Conway, Early Quaker Thought, and the New Science.” Quaker History96 (1): 24-35.

Clucas, Stephen. 2000. “The Duchess and the Viscountess: Negotiations between Mechanism and Vitalism in the Natural Philosophies of Margaret Cavendish and Anne Conway.” In-between: Essays and Studies in Literary Criticism 9 (1-2): 125-136.

Colie, Rosalie Littell. 1957. Light and Enlightenment: a Study of the Cambridge Platonists and the Dutch Arminians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coudert, Allison. 1975. “A Cambridge Platonist’s Kabbalist Nightmare.” Journal of the History of Ideas 36 (4): 633-652.

______. 1976. “A Quaker-Kabbalist Controversy: George Fox’s Reaction to Francis Mercury van Helmont.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 39: 171-189.

______. 1995. Leibniz and the Kabbalah. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

______. 1998. “Anne Conway: Kabbalist and Quaker.” In The Impact of the Kabbalah in the Seventeenth Century: The Life and Work of Francis Mercury van Helmont, 1614-1698, edited by Allison Coudert. Leiden: Brill.

______. 1998. The Impact of the Kabbalah in the Seventeenth Century: The Life and Work of Francis Mercury van Helmont, 1614-1698. Leiden: Brill.

Critchley, M. 1937. “The Malady of Anne, Viscountess Conway.” King’s College Hospital Gazette 16: 44-9.

Crocker, Robert. 2003. Henry More, 1614-1687: a Biography of the Cambridge Platonist. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Derksen, Louise D. 1998. “Anne Conway’s Critique of Cartesian Dualism.” Conference: Twentieth World Congress of Philosophy, Boston, Massachusetts U.S.A. Link.

Duran, Jane. 1989. “Anne Viscountess Conway: A Seventeenth Century Rationalist.” Hypatia 4 (1): 64-79.

______. 1996. “Anne Viscountess Conway: A Seventeenth-Century Rationalist.” In Hypatia’s Daughters: Fifteen Hundred Years of Women Philosophers . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

______. 2006. “Anne Conway.” In Eight Women Philosophers: Theory, Politics, and Feminism, edited by Jane Duran. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Frankel, Lois. 1985. “Motion and Emanation in the Principles of Anne Conway.” Conference: New Trends in Feminist Philosophy, Ohio State University.

Gabbey, Alan. 1977. “Anne Conway et Henry More: Lettres sur Descartes (1650–1651).” Archives de Philosophie 40: 379-404.

Gilbert, Pamela K. 1997. “The ‘Other’ Anne Finch: Lady Conway’s ‘Duelogue’ of Textual Selves.” Essays in Arts and Sciences 26: 15-26.

Gordon-Roth, Jessica. 2018. “What Kind of Monist is Anne Finch Conway?” Journal of the American Philosophical Association 4: 280–297.

Green, Joseph J. 1910. “Correspondence of Anne, Viscountess Conway, Quaker Lady, 1675.” Journal of the Friends Historical Society 7: 7-17, 49-55.

Hutton, Sarah. 1994. Ancient Wisdom and Modern Philosophy: Anne Conway, F.M. Van Helmont and the Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interchange of Ideas. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

______. 1995. “Anne Conway Critique d’Henry More: L’Esprit, Substance, et la Matière.” Archives de Philosophie 58 (3): 371-384.

______. 1996. “Henry More and Anne Conway on Preexistence and Universal Salvation.” In ‘Mind Senior to the World’. Stoicismo e Origenismo Nella Filosofia Platonica del Seicento Inglese, edited by Baldi. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

______. 1996. “Of Physic and Philosophy: Anne Conway, F. M. van Helmont and Seventeenth- Century Medicine.” In Religio Medici: Medicine and Religion in Seventeenth-Century England, edited by Ole Peter Grell and Andrew Cunningham. Aldershot, England: Scolar.

______. 1997. “Anne Conway, Margaret Cavendish and Seventeenth Century-Scientific Thought.” In Women, Science and Medicine 1500-1700, edited by Lynette Hunter and Sarah Hutton.

______. 1997. “De Alteriteit van de Geschiedenis: Over Anne Conway (1630-1679) en Mary Astell (1666-1731).” In Het Denken van der Ander, edited by J Hermsen. Kampen: Kok Agora.

______. 1999. “Anne Conway and the Kaballah.” In Judaeo-Christian Intellectual Culture in the Seventeenth Century: a Celebration of the Library of Narcissus Marsh (1638-1713), edited by Allison Coudert, Sarah Hutton and R.H. Popkin. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

______. 1999. “On an Early Letter by Anne Conway.” In Donne Filosofia e Cultura nel Seicento, edited by Pina Totaro, pp. 109-15. Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche.

______. 2004. Anne Conway: a Woman Philosopher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

______. 2011. “Sir John Finch and Religious Toleration: an Unpublished letter to Anne Conway.” In La Centralita del Dubbio, edited by Antonio Rotondo, Luisa Simonutti and Camilla Hernanin. Florence: Olschki.

Hutton, Sarah, M Mulsow, and J Rohls. 2005. “Platonism and the Trinity: Anne Conway, Henry More and Christoph Sand.” In Socinianism and Arminianism : Antitrinitarians, Calvinists, and Cultural Exchange in Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Martin Mulsow and Jan Rohls. Leiden: Brill.

Hutton, Sarah. 2005. “Women Philosophers and the Early Reception of Descartes: Anne Conway and Princess Elisabeth.” In Receptions of Descartes: Cartesianism and anti-Cartesianism in Early Modern Europe, edited by Tad M. Schmaltz. London: Routledge.

Kraus, Robert. 1986. “A Brief History of the Cabala and its Influence on the Renaissance Philosophy of Anne Conway.” Guilford Review 23: 36-41.

La Nave, Francesco. 2006. “The Central Role of Suffering in Anne Conway’s Philosophy.” Bruniana & Campanelliana: Ricerche Filosofiche e Materiali Storico-Testuali 12 (1): 177-182.

Lascano, Marcy P. 2013. “Anne Conway: Bodies in the Spiritual World.” Philosophy Compass 8 (4): 327-336.

Lobsien, Verena Olejniczak. 2001. “Skeptische Phantasie–Eine andere Geschichte der frühneuzeitlichen Literatur: Nikolaus von Kues, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Burton, Herbert, Milton, Marvell, Margaret Cavendish, Aphra Behn, Anne Conway.” Zeitschrift fuer Aesthetik und allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft 45 (2): 318-324.

Loptson, Peter. 1982. “Introduction to Anne Conway.” In The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, edited by Peter Loptson. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

______. 1995. “Anne Conway, Henry More, and their World.” Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review 34 (1): 139-46.

Martensen, Robert. 2008. “A Philosopher and Her Headaches: The Tribulations of Anne Conway.” Philosophical Forum 39 (3): 315-326.

McRobert, Jennifer. 2000. “Anne Conway’s Vitalism and her Critique of Descartes.” International Philosophical Quarterly 40 (1): 21-35.

Mercer, Christia. 2012. “Knowledge and Suffering in Early Modern Philosophy: G.W. Leibniz and Anne Conway.” In Emotional Minds, edited by Sabrina Ebbersmeyer. De Gruyter.

______. 2012. “Platonism in Early Modern Natural Philosophy: the Case of Leibniz and Conway.” In Neoplatonism and the Philosophy of Nature, edited by James Wilberding and Christoph Horn.

______. Forthcoming. “Anne Conway’s Metaphysics of Sympathy.” In Feminist History of Philosophy: The Recovery and Evaluation of Women’s Philosophical Thought, edited by Eileen O’Neill and Marcy Lascano. Dordrecht: Springer.

Merchant, Carolyn. 1979. “The Vitalism of Anne Conway: Its Impact on Leibniz’s Concept of the Monad.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 17 (3): 255-269.

______. 1986. “Anne Conway: Quaker and Philosopher.” Guilford Review: 2-10.

______. 1989. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. New York: Harper & Row.

Nelson, Holly Faith, and Sharon Alker. 2011. “Conway: Dis/ability, Medicine, and Metaphysics.” In The New Science and Women’s Literary Discourse: Prefiguring Frankenstein, edited by Judy A. Hayden. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Origgi, Gloria. 2008. “What’s in My Common Sense?” Philosophical Forum 39 (3): 327-335. Owen, Gilbert Roy. 1937. “The Famous Case of Lady Anne Conway.” Annals of Medical History 9: 567-71.

Parageau, Sandrine. 2008. “The Function of Analogy in the Scientific Theories of Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673) and Anne Conway (1631-1679).” Etudes Epistémè 14: 89-104.

Popkin, R.H. 1990. “The Spiritualistic Cosmologies of Henry More and Anne Conway.” In Henry More (1614-1687): Tercentenary Studies, edited by S. Hutton. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Powicke, F.J. 1921. “Henry More, Cambridge Platonist; and Lady Conway, of Ragley, Platonist and Quakeress.” Friends Quarterly Examiner 55: 199-220.

Schlierkamp, Kathrin. 2012. Mind the Gap: zum Verhältnis von Körper und Seele bei Marie le Jars de Gournay, Elisabeth von der Pfalz, Anne Conway und Mary Astell . Aachen: ein-FACH-vlg.

Schroeder, Steven. 2007. “Anne Conway’s Place: a Map of Leibniz.” The Pluralist 2 (3): 77-99.

4. Philosophy & Teaching

This section is forthcoming. Our team is working with the Advisory Board on materials interpreting Conway’s philosophical work and accompanying teaching materials. In the meantime, please see the Teaching part of the website for sample syllabi.

A useful teaching resource on Conway and Leibniz is Karen Warren’s and Jane Duran’s chapter in Warren’s edition An Unconventional History of Western Philosophy: Conversations Between Men and Women Philosophers (2009). This includes an introduction by Warren, excerpts of writings by Leibniz and Conway, a commentary by Duran, and student-friendly “questions for reflection.”

5. Correspondence

There are two comprehensive sources of Conway correspondence. The first is The Conway Lettersedited by Marjorie Hope Nicolson in 1930, which contains biographical information and correspondence. The second is the revised edition of The Conway Letters by Sarah Hutton in 1992. The majority of the letters in the correspondence are by Henry More, a leading Cambridge Platonist philosopher. Given that Conway did not publish during her lifetime, the two editions provide an invaluable window into Conway’s philosophical training and development, as well as into her personal, social, historical, and intellectual environment.

Nicolson pioneered biographical research on Conway. The 1930 edition was the first publication to make available the correspondence between Conway and More in print, and to draw an intellectual connection between More – a recognized, if not canonical, philosopher – and Conway, the hitherto neglected woman philosopher and his mentee. Nicolson’s work also laid the groundwork for future research on various aspects of More’s philosophy, such as his influence on the reception of Cartesianism in England and his views on natural philosophy. The Nicolson collection of letters remains the starting point for Conway scholarship, although some new information has emerged since its publication.

A key feature of the Nicolson edition is that it focuses mainly on Conway’s personal and social life, and that of her friends and family. It was not conceived as an intellectual biography, and for this reason the 1930 edition intentionally omits some philosophically relevant letters and passages. For example, the edition does not include some of the early correspondence between More and Conway on the topic of Cartesianism. The revised edition by Hutton includes the complete set of letters between Conway and More, as well as some additional correspondence; for example, an additional letter from More to the natural philosopher Robert Boyle. The edition also reproduces as far as possible the original manuscript format.

Content of letters

More than half of the correspondence is from More to Conway, and covers a variety of personal, social and philosophical topics. Most of the letters penned by Conway are written to More, (although only a little more than a dozen remain) and to her erudite father-in-law, Lord Conway. There are also a dozen letters to Conway from her brother John Finch, who originally introduced his mentor More to his beloved sister. The edition also includes three letters from More to Robert Boyle, a letter from More to Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle (see Cavendish Section 5.3) and three letters to Conway from the Quakers George Keith, William Penn, and Lilias Skene.

An overview of the two editions and the contents of the correspondence can be found in Sarah Hutton’s “Introduction to the Revised Edition” from 1992.

Editions of Conway correspondence

Hutton, Sarah, and Marjorie Hope Nicolson, eds. 1992. The Conway Letters: the Correspondence of Anne, Viscountess Conway, Henry More, and their Friends, 1642-1684. Revised Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nicolson, Marjorie Hope, ed. 1930. Conway Letters: the Correspondence of Anne, Viscountess Conway, Henry More, and their Friends, 1642-1684. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Breakdown of letters

Source: the 1992 revised edition, including additional letters in Appendices.

| Total | 307 letters |

| From Conway | 39 |

| Including: | 2 to Edward Conway |

| 14 to Henry More | |

| 22 to Lord Conway | |

| 1 to Sir George Rawdon | |

| Total to Conway | 182 |

| Henry More to Conway | 165 |

| John Finch to Conway | 11 |

| Others to Conway | 1 from George Keith |

| 3 from Lady Francis Clifton | |

| 1 from Lilias Skene | |

| 8 from Lord Conway | |

| 1 from Robert Gell | |

| 1 from Sir Heneage Finch | |

| 1 from Sir Thomas Baines | |

| 1 from Thomas Bromley | |

| 1 from William Penn | |

| Non-Conway | 44, of which three are inheritance related documents |

A sortable table of the correspondence contained in Hutton & Nicolson (1992) is available for download. Please note that the file contains several worksheets reflecting the breakdown.

Spreadsheet overview: Excel file

Forthcoming: a new version of the spreadsheet that will include brief descriptions of the letter contents.

Manuscript sources

The following manuscript information is cited from Hutton & Nicolson (1992) and Sarah Hutton’s intellectual biography of Conway:

Hutton, Sarah. 2004. Anne Conway: a Woman Philosopher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Manuscript locations

See Hutton 2004, Introduction to the Revised Edition, pg. xiii.

British Library, London: Conway Papers Collection. Mainly contained in Additional Manuscript 23,216, but also Additional Manuscript MSS 23,214, 23,215, and 23,217.

Christ’s College, Cambridge University: MS 21.

State Papers.

Rawdon Papers:

According to Hutton (pg. xiii, ft. 9) these were “published by Edward Berwick as The Rawdon Papers consisting of Letters on Various Subjects, Literary, Political and Ecclesiastical to and from Dr. John Bramhall (London, 1819). They were originally part of the collection of Hastings MSS now in the Huntington Library, California. For an account of these papers, see the Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on the Manuscripts of the Late Reginald Rawdon Hastings, Esq., ed. F. Bickley (London, 1930) and the “Summary Report on the Hastings Manuscripts,” Huntington Library Bulletin, V (1934).”

Burley-on-the-Hill Finch Papers:

According to Hutton (pg. xiii, ft. 9) “The Burley-on-the Hill papers are now mostly deposited in the Leicestershire Record Office. For an account of them, see the Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on the Manuscripts of Allan George Finch Esq. of Burley on the Hill, Rutland (London, 1913).”

Friends’ House, London: Box Meeting Room Accounts. 1681-1750.

Conway’s letter manuscripts

Cited from Hutton 2004, pg. 244.

Christ’s College, Cambridge University: MS 21. Letters of Anne Conway and Henry More.

British Library, London: MS Additional.

- 23,214: Letters from Conway to her husband Edward Conway.

- 23,215: Letters to Conway from her brother John Finch and his companion Thomas Baines.

- 23, 216: Letters from Henry More and others.

- 23,217: Letters to Conway from various Quakers.

- 38,855, folio 108: Letter to Conway from her brother John Finch.

Friends’ House, London: Box Meeting Room Accounts, 1681-1750. Conway’s legacy paid by Van Helmont.

Other letter manuscripts relevant to Conway

Cited from Hutton 2004, pg. 245.

Amagh Robinson Library, Armagh, Ireland: MS g. III. 15, Conway Library Catalogue.

Leicester and Rutland County Record Office, Leicester, United Kingdom: Finch papers, MS DG7 lit. 9.

British Library, London:

- MS Sloane 35: catalogue of Stubbe’s books.

- MS Sloane 530: ‘Some Observations of Francis Mercury van Helmont’s’ transcribed by Daniel Foote.

- MS Stowe 205.

- MS Additional 22,911: ‘An Account of ye Master’s Lodgings in ye College and of his private Lodge by itself.’

- MS Additional 4,293: Sir Robert Boyle on the Irish healer Valentine Greatrakes.

- MSS Additional 4,280 and 4,278: Pell-Cavendish letters.

Friends’ House Library, London: Spence MS 378.

Public Record Office, London: SP 120/7, list of Conway books, and Prob 11/160 ff. 503-505, the will of Sir Heneage Finch.

Bodleian Library, Oxford University: MS Locke 17. Adam Boreel poem on Lady Conway.

Huntington Library, California, USA: Hastings MSS. Correspondence of Edward, 3rd Viscount of Conway and Sir George Rawdon.

Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, Germany: Cod. Guelf. Extrav. 30.4. Correspondence of Knorr von Rosenroth.

5.1 Correspondence with Henry More

Henry More (1614–1687) was a leading Cambridge Platonist philosopher, poet, theologian and a long-term close tutor, friend and mentor of Conway until her death in 1679. He was also a fellow of the Royal Society. More than half (c. 169) of the extant letters in The Conway Letters consist of correspondence between More and Conway, from 1650-1678. There are 155 letters extant from More, but unfortunately only 14 of Conway’s letters to More remain. The content of her letters can therefore be reconstructed only indirectly. (Please note that an updated spreadsheet in Section 5 with brief descriptions of the letters’ contents is forthcoming.) Also extant is More’s dedication of his work An Antidote Against Atheism (1653) to Conway.

Background

It is highly likely that Conway came into contact with the Cambridge Platonist philosopher Henry More through her half-brother John Finch. Finch was a student of Henry More at Christ’s College, Cambridge University, where he received his MA degree in 1649. Before he left for Europe in 1651, Finch introduced More to Conway, and More agreed to tutor Conway in philosophy by means of correspondence: in a way then, Conway received a long distance “university” education. At the time of their acquaintance, More was a rising star in academic circles, and would eventually achieve international renown as a philosopher. He already maintained extensive contacts with both English and Continental philosophers, including René Descartes, with whom he corresponded between 1648-1649. Some scholars argue that More played a key role in introducing Descartes’s philosophy to England, and he was therefore well placed to discuss it with Conway.

Contents of letters

The correspondence between More and Conway begins with a tutorial discussion of Descartes, specifically his Principia Philosophiae (1644), which More translated into English for Conway, as she had not yet fully mastered Latin. They also discussed Descartes’s La Dioptrique (1637). Some scholars interpret More’s pedagogical method in these letters as an academic style objection-replies approach, where he encourages his student to critically evaluate the arguments put forth. These early pedagogical letters discuss topics such as arguments for the existence of God, the existence of vacuum, and the properties of color.

Subsequent letters discuss a variety of personal, theological and philosophical topics. Personal topics include Conway’s family events, such as the death of her young son, personal health, and Conway’s search for a medical cure from well respected physicians, healers and natural philosophers of the day such as William Harvey, Valentine Greatrakes and Robert Boyle. Theological discussions cover, for example, religious enthusiasm and millenarianism, and the various new Christian religious movements that appeared in England in the later 1600s, such as the Quakers, Behmenists, Socianists, and Familists (see also Section 5.4).

The extant letters do not discuss More’s and Conway’s philosophy directly. Their philosophical views are discussed in the broader theological context of discussions regarding, for example, the Kabbalah and religious enthusiasm. It is also difficult to assess to what extent Conway may have influenced More’s philosophical work. According to some scholars, More published Conjectura Cabbalistica(1655) at Conway’s request, and changed a number of his views as a result of the correspondence. For example, he seems to have attenuated his views on the Quakers in respect of Conway.

Scholars such as Sarah Hutton also suggest that Conway’s correspondence with Henry More, Francis Mercury Van Helmont, and the Quaker leader George Keith, in addition to other texts by these philosophers, indicates that Conway was a dominant participant in their philosophical debates. She argues that it is possible that Conway may have in fact been the co-author of Van Helmont’s kabbalistic texts Adumbratio Kabbalae Christianae (1677) and Two Hundred Queries Concerning the Revolution of Human Souls (1684), which were the product of these debates.

More’s dedication to Antidote Against Atheism

More dedicated his work An Antidote Against Atheism (1653) to Conway. The work discusses the materialist philosophy of Thomas Hobbes and arguments for the existence of God. The following is a modern transcription of the dedication. The dedication was subsequently edited: the spelling and some of the grammar was modernized to make it more accessible and a pleasure to read.

More dedicated his work An Antidote Against Atheism (1653) to Conway. The work discusses the materialist philosophy of Thomas Hobbes and arguments for the existence of God. The following is a modern transcription of the dedication. The dedication was subsequently edited: the spelling and some of the grammar was modernized to make it more accessible and a pleasure to read.

Please note that the original transcription comes from the Early English Books Online database. The original copy was provided courtesy of the McAlpin Collection of British History and Theology, the Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Digital copy of original: PDF file

To the Honourable, the Lady Anne Conway.

Madame,

The high opinion or rather certain knowledge I have of your singular wit and virtues, has emboldened, or to speak more properly, commanded me to make choice of none other than yourself for a patroness of this present treatise. For besides that I do your Ladyship that right as also this present age and succeeding posterity, as to be a witness to the world of such eminent accomplishments and transcendent worth; so I do not a little please myself, while I find myself assured in my own conceit that Cebes his mysterious and judicious piece of morality hung up in the temple of Saturn, which was done in way of divine honor to the wisdom of the deity, was not more safely and suitably placed then this careful draught of natural theology or metaphysics, which I have dedicated to so noble, so wise, and so pious a personage. And for my own part it seems to me as real a point of religious worship to honor the virtuous as to relieve the necessitous, which Christianity terms no less then a sacrifice. Nor is there anything here of hyperbolism or high-flown language, it being agreed upon by all sides, by prophets, apostles, and ancient philosophers, that holy and good men are the temples of the living God. And verily the residence of divinity is so conspicuous in that heroic pulchritude of your noble person, that Plato if he were alive again might find his timorous supposition brought into absolute act, and to the enravishment of his amazed soul might behold virtue become visible to his outward sight. And truly Madame, I must confess that so divine a constitution as this, wants no preservative, being both devoid and incapable of infection; and that if the rest of the world had attained but to the least degree of this sound complexion and generous frame of mind, nay if they were but brought to an equilibrious indifference, and, as they say, stood but neutrals, that is, if as many as are supposed to have no love of God, nor any knowledge or experience of the divine life, did not out of a base ignorant fear irreconcilably hate Him, assuredly this antidote of mine would either prove needless and superfluous, or, if occasion ever called for it, a most certain cure. For this truth of the existence of God being as clearly demonstrable as any theorem in mathematics, it would not fail of winning as firm and as universal assent, did not the fear of a sad after-clap pervert men’s understandings, and prejudice and interest pretend uncertainty and obscurity in so plain a matter. But considering the state of things as they are, I cannot but pronounce, that there is more necessity of this my antidote then I could wish there were. But if there were less or none at all, yet the pleasure that may be reaped in perusal of this treatise, (even by such as by an holy faith and divine sense are ever held fast in a full assent to the conclusion I drive at) will sufficiently compensate the pains in the penning thereof. For as the best eyes and most able to behold the pure light do not unwillingly turn their backs of the sun to view his refracted beauty in the delightful colors of the rainbow; so the perfectest minds and the most lively possessed of the divine image, cannot but take contentment and pleasure in observing the glorious wisdom and goodness of God so fairly drawn out and skillfully variegated in the sundry objects of external nature. Which delight though it redound to all, yet not so much to any as to those that are of a more philosophical and contemplative constitution; and therefore Madame, most of all to yourself, whose genius I know to be so speculative, and wit so penetrant, that in the knowledge of things as well natural as divine you have not only out done all of your own sex, but even of that other also, whose ages have not given them overmuch the start of you. And assuredly your Ladyship’s wisdom and judgment can never be highly enough commended, that makes the best use that may be of those ample fortunes that divine providence has bestowed upon you. For the best result of riches, I mean in reference to ourselves, is, that we finding ourselves already well provided for, we may be fully masters of our own time: and the best improvement of this time is the contemplation of God and nature, wherein if these present labors of mine may prove so grateful unto you and serviceable, as I have been bold to presage, next to the winning of souls from atheism, it is the sweetest fruit they can ever yield to

Your Ladyship’s Humbly Devoted Servant Henry More.

Primary source

More, Henry. 1653. An Antidote Against Atheisme, or, an Appeal to the Natural Faculties of the Minde of Man, Whether There be not a God by Henry More. London: Printed by Roger Daniel.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5.2 Correspondence with John Finch

Finch (1626–1682) was Conway’s half-brother, from their father’s previous marriage, and the two siblings were very close. Along with Henry More and Francis Mercury Van Helmont, Finch had profound intellectual influence on his sister, and actively supported and encouraged her philosophical interests throughout her life. Finch was a physician, a virtuoso member of the Royal Society, and a diplomat, and therefore spent most of his life traveling abroad. His experience abroad also gave Conway access to new worlds and ideas: for example, his experience as the ambassador to the Ottoman Empire engendered Conway’s interest in Islam. Finch’s letters attest to the fondness that he had for his sister even when they were far apart. The alleged portraits by Van Hoogstraten (see Section 1.2) also show this, as they depict the pet dog Julietto that Finch sent to his sister as a gift all the way from Italy.

Background

Finch attended Balliol College at Oxford for his bachelor degree, and then Christ’s College at Cambridge for his MA, which he completed in 1649. It is at Cambridge that he met Henry More, whom he (most likely) introduced to Conway. At Cambridge he also met Thomas Baines (c. 1622/4-1681), who became his lifelong companion and who also corresponded with Conway (there is one extant letter in the correspondence from him to Conway). In 1651, Finch left with Baines for Europe in order to study medicine in Padua, Italy, and he gained an MD in 1657. He subsequently became a respected physician and anatomist known for his special interest in brain anatomy, perhaps because of Conway’s illness. Finch held academic posts at the University of Padua and the University of Pisa, and became a member of the Accademia del Cimento in Florence, and Prince Leopoldo Medici’s academic circle. In 1663 he was elected a member of the Royal Society and became one of its foreign correspondents. In 1665 he was appointed the English resident in Florence and in 1671, he was appointed ambassador to the court of the Ottoman Empire. This is also probably the last time that he saw Conway in person before his departure. He returned to England only in 1681 after Conway’s death and passed away himself in 1682.

Finch did not publish any treatises in his lifetime, but an unpublished manuscript on natural philosophy was found after his death. The work discusses materialist views of nature, and the views of Descartes and Henry More.

The letters

The Conway Letters (1992) correspondence includes eleven letters from Finch to his beloved sister Anne, ten of which were written between 1651-1653 and one in 1657. The correspondence also includes one letter from Finch to Conway’s husband, Edward Conway, from 1653. Other letters between Conway and Finch appear to remain unpublished (research forthcoming.) The letters discuss mostly personal matters, but also touch upon some philosophical topics. The personal topics range from Conway’s illness to Finch’s experiences in Italy, to descriptions of religious customs in Turkey and Van Helmont’s reputation as a physician. In Letter 37 from April 1653, Finch also mentions More’s Antidote to Atheism (1653), and discusses his purchases of various works in natural philosophy that he had translated and sent to Conway, including work by Copernicus. The letters also indicate that Finch may have shared drafts of his treatise with Conway. An unpublished letter from Finch to Conway discusses Conway’s conversion to Quakerism, More’s philosophy, and Finch’s views on religious toleration (see Hutton 2011).

References

Hutton, Sarah 2009. Finch, Sir John (1626–1682). In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition Oct. 2009), edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hutton, Sarah. 2011. “Sir John Finch and Religious Toleration: an Unpublished letter to Anne Conway.” In La Centralita del Dubbio, edited by Antonio Rotondo, Luisa Simonutti and Camilla Hernanin, 287-304. Florence: Olschki.

Underwood, T. L. 1978. “Sir John Finch and Viscountess Anne Conway: Two Unpublished Letters.” Quaker History 67 (2): 112-121.

Images of John Finch and Thomas Baines forthcoming.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5.3 Interaction with Francis Mercury von Helmot

Apart from her brother John Finch and her mentor Henry More, the third most influential scholar in Conway’s life was the natural philosopher, physician, alchemist and Christian kabbalist Francis Mercury Van Helmont (1614-1698). There appears to be no extant correspondence between Conway and Van Helmont, but he played a crucial role in shaping and disseminating Conway’s philosophy and therefore warrants discussion here.

Francis Mecury Van Helmont by Sir Peter Lely, c. 1670-1

Background

Conway initially sought out Van Helmont’s services as a physician in 1670, but very quickly became close friends with him and he remained a guest and intellectual companion at Ragley until her death in 1679. Van Helmont introduced Conway to Quakerism and in 1677 converted to Quakerism with her. He was also instrumental in developing Conway’s interest in Lurianic kabbalist philosophy. Some scholars argue that her philosophy is heavily influenced by it, and that it is also why she discusses Spinoza’s philosophy in her Principles. It is Van Helmont who posthumously published the Principlesin 1690 (in Latin) on the basis of her handwritten notes. An unpublished preface to the Principles, alternatively attributed to Van Helmont or to Henry More, was reprinted in Ward’s The Life of the Learned and Pious Dr. Henry More (1710). (See Section 2.1 for a downloadable copy.)

Francis Mercury was the son of the Flemish natural philosopher, chymist and physician Jan Baptiste Van Helmont (1580-1644) and is often confused with him, even in scholarly literature: he is known for publishing his father’s works in Ortus Medicinae (1648) and for promoting his natural philosophy. Jan Baptiste’s philosophy was broadly Paracelsian, and he is also known for his early use of observation and experiment in his studies. Jan Baptiste’s approach became popular in England through the Hartlib circle, and his followers included natural philosophers such as Robert Boyle. His son Francis Mercury also became a physician, and diplomat attached to the court of Frederick V, Elector Palatine. It is following a mission on behalf of the Elector’s daughter Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia (who had corresponded with Descartes) that he became acquainted with Conway.

Conway’s husband Edward Conway and her brother John Finch had unsuccessfully tried to contact Van Helmont earlier, in the 1650s, in order to consult him regarding Conway’s illness. When Van Helmont arrived in England in 1670, he contacted Henry More regarding Christian Knorr von Rosenroth’s (1636-1689) work on the Kabbala Denudata (volume one published in 1677/8 and volume two in 1684) and it was at More’s behest that Van Helmont finally came to Conway’s assistance. He was not able to cure her, but became her intellectual companion instead.

The Kabbalah & Quakerism

Van Helmont was deeply influenced by the research of the Hebrew scholar and Christian kabbalist Christian Knorr von Rosenroth into Lurianic Kabbalah, as well as by the Quaker groups that he had encountered at Frederick’s court. When Conway met Van Helmont in 1670, she was already familiar with some Christian interpretations of the Kabbalah, and scholars suggest that More published his Conjectura Cabbalistica at her request fifteen years earlier. Van Helmont introduced Conway and More to von Rosenroth’s work, and had his manuscripts of Kabbalah Denudata sent to More, who then shared them with Conway. Conway and More both subsequently corresponded with von Rosenroth. There is one extant letter from von Rosenroth to Conway (see Hutton 2004, pg. 161.)

The last ten years of Conway’s life saw active philosophical discussions on the subject of the Kabbalah and Quakerism, between Conway, More, Van Helmont, and the Quaker leader George Keith. These discussions are documented in the Conway correspondence and other texts by these philosophers. Scholars agree that the discussions had an important influence on Conway’s thought, and it is most likely during the 1670s that she composed the philosophical notes that served as the basis for her Principles. During this time Van Helmont also published the Latin version of his Cabbalistical Dialogue, which was included in the first volume of the Kabbala Denudata in 1677/8, and subsequently published in English in 1684. According some scholars, Van Helmont’s works Adumbration Kabbalae Christianae (1684) and Two Hundred Queries Concerning the Revolution of Human Souls (1684) are indebted to these discussions and perhaps even to Conway herself.

Impact on Conway’s legacy

After Conway’s death in 1679, Van Helmont traveled to the Netherlands, where he befriended the philosopher John Locke. He also presented a copy of Conway’s Principles to his friend Leibniz, whose annotated copy is housed at the Leibniz Archiv at the Niedersachsische Bibliothek in Hannover, Germany. Van Helmont visited Locke and Lady Masham at Oates in 1693, and it is possible that through him Locke and Masham may have become exposed to Conway’s ideas, although no record remains of this. (See Coudert 1998 for more information on Locke’s reception of Van Helmont’s philosophy and the Kabbalah.)

Selected secondary sources

Brown, Stuart. 1997. “F.M. Van Helmont: His Philosophical Connections and the Reception of his Later Cabbalistic Philosophy.” In Studies in Seventeenth-Century European Philosophy, 97-116. New York: Clarendon Press.

Brown, Stuart. 2008. Helmont, Franciscus Mercurius Van, Baron of Helmont and Merode in the nobility of the Holy Roman Empire (1614–1698). In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Coudert, Allison. 1975. “A Cambridge Platonist’s Kabbalist Nightmare.” Journal of the History of Ideas36 (4): 633-652.

Coudert, Allison. 1998. The Impact of the Kabbalah in the Seventeenth Century: The Life and Work of Francis Mercury van Helmont, 1614-1698. Leiden: Brill.

Coudert, Allison. 1998. “Anne Conway: Kabbalist and Quaker.” In The Impact of the Kabbalah in the Seventeenth Century: The Life and Work of Francis Mercury van Helmont, 1614-1698, edited by Allison Coudert, 177-219. Leiden: Brill.

Hutton, Sarah. 1996. “Of Physic and Philosophy: Anne Conway, F. M. van Helmont and Seventeenth-Century Medicine.” In Religio Medici: Medicine and Religion in Seventeenth-Century England, edited by Ole Peter Grell and Andrew Cunningham, 228-246. Aldershot, England: Scolar.

Hutton, Sarah. 1999. “Anne Conway and the Kaballah.” In Judaeo-Christian Intellectual Culture in the Seventeenth Century: a Celebration of the Library of Narcissus Marsh (1638-1713), edited by Allison Coudert, Sarah Hutton and R.H. Popkin. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Kraus, Robert. 1986. “A Brief History of the Cabala and its Influence on the Renaissance Philosophy of Anne Conway.” Guilford Review 23: 36-41.

Sherrer, Grace B. 1958. “Philalgia in Warwickshire: F. M. Van Helmont’s Anatomy of Pain Applied to Lady Anne Conway.” Studies in the Renaissance 5: 196-206.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

5.4 Correspondence with Quakers

There are three extant letters to Conway from the Quaker leaders George Keith (1638?-1716), William Penn (1644-1718), and Lilias Skene (1626/7-1697). Although these letters do not have philosophical content, they are relevant for a broader understanding of Conway’s philosophy, as it is inextricably linked to her theological views: one interpretation of her philosophical work is that it drew on unorthodox theological views (in her time), such as those expressed in the Judaic mystic teachings of the Kabbalah and various new Christian doctrines. Some scholars also interpret the theory of substance expressed in her Principles as directly reflecting her theological views on the doctrine of the Trinity, and trace her interests in the Kabbalah and Quakerism to the same intellectual roots. The kind of philosophical questions Conway asked were also influenced by her illness; for example, the question of how the mind and the body are related is tied to the question of how it is possible for God to allow human suffering in this world.

William Penn, by John Hall, 1773

William Penn, by John Hall, 1773

Background

Conway grew up as an Anglican, but in a social and political environment that was marked by religious upheaval and theological debate. The Conway family was liberal in its religious views, as was Conway’s mentor Henry More, who is considered one of the fathers of “latitudarianism,” a liberal movement within Anglicanism. Conway’s correspondence with Henry More also indicates that she had an active interest in theological issues and the different religious groups that were making an appearance in England in the later 1600s. The early correspondence discusses theological topics such as nature of human and animal souls, the relationship between soul and body, and the implications of this relationship for the salvation of the soul. Later letters discuss topics such as religious enthusiasm, millenarianism, groups such as the Quakers, Behmenists, Socianists, and Familists, and new theological doctrines such as Mortalism and Psychopannychism. Some scholars also suggest that Conway’s philosophy was influenced by the writings of the Church father Origen, whose writings enjoyed a revival among Cambridge Platonists like More.

The conversion

Conway converted to Quakerism shortly before her death (1679), probably sometime in 1677-1678. It is probably her physician and mentor Francis Mercury Van Helmont who introduced Conway to the Society of Friends, whose representatives he first met during his time on the Continent. Van Helmont also became a Quaker. Neither her family nor Henry More viewed the conversion favourably, but they respected Conway’s wishes. More even engaged in scholarly debate with some of the Quaker leaders, such as George Keith, and corresponded on the subject of Christology with William Penn.

Conway’s interest in the group dates to the late 1660s, and became much more active in the few years before her death. Conway met George Keith in 1675, Lilias Skene in 1677, and she corresponded with William Penn who was unable to meet her in person. She also had contact with other Quakers. According to some scholars, Conway converted for a number of reasons: she identified her own physical suffering with the hardships faced by the group, she found the theological underpinnings attractive, and she identified parallels between Quaker beliefs and the Kabbalah.

Manuscripts

| Letter No. | Chapter | Author | Recipient | Year | Date (Julian) | Manuscript Sources |

| 250 | 7 | William Penn | Lady Conway | 1675 | Oct-20 | Add. MSS 23,217, f. 14 |

| 266 | 7 | George Keith | Lady Conway | 1677 | Jun-06 | Add. MSS 23,217, f. 21 |

| 267 | 7 | Lilias Skene | Lady Conway | 1677 | Sep-16 | Add. MSS 23,217, f. 23 |

References

Corse, Taylor, and Allison Coudert, eds. 1996. The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, Cambridge texts in the history of philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (See especially Introduction.)

DesBrisay, Gordon. 2004-15. Skene, Lilias (1626/7–1697). In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition), edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Link.

Chamberlain, J.S. 2004-15. Keith, George (1638?–1716). In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(Online Edition Oct. 2005), edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Link.

Geiter, Mary K. 2004-15. Penn, William (1644–1718). In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(Online Edition Jan. 2007), edited by David Cannadine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Link.

Hutton, Sarah. 2004. Anne Conway: a Woman Philosopher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (See especially Ch. 3 on Religion, and Ch. 9 on Quakerism.)

Selected secondary sources

Coudert, Allison. 1976. “A Quaker-Kabbalist Controversy: George Fox’s Reaction to Francis Mercury Van Helmont.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 39: 171-189.

Coudert, Allison. 1998. “Anne Conway: Kabbalist and Quaker.” In The Impact of the Kabbalah in the Seventeenth Century: The Life and Work of Francis Mercury Van Helmont, 1614-1698, edited by Allison Coudert, 177-219. Leiden: Brill.

Benfey, Theodor. 1986. “Anne Conway’s Interaction with Science, Politics, Medicine and Quakerism.” Guilford Review 23:14-23.

Byrne, David. 2007. “Anne Conway, Early Quaker Thought, and the New Science.” Quaker History96 (1): 24-35.

Merchant, Carolyn. 1986. “Anne Conway: Quaker and Philosopher.” Guilford Review: 2-10.

Powicke, F.J. 1921. “Henry More, Cambridge Platonist; and Lady Conway, of Ragley, Platonist and Quakeress.” Friends Quarterly Examiner 55:199-220.

For image sources and permissions see our image gallery.

6. Connections

Thanks to the support of her well connected family and her three mentors John Finch, Henry More, and Francis Mercury Van Helmont, Conway had access to the ideas of eminent natural philosophers in England, as well as on the Continent. Since she suffered from painful headaches all her life, she preferred to pursue philosophy in the seclusion of her manor and in the close circle of her mentors.

The below table provides brief descriptions of her intellectual connections, and where possible, indicates how these were related to others who influenced her thought. It also includes some of the most prominent Quakers and physicians with Conway had contact.

The following sections also present quotes by well known male philosophers, which express their views of Conway.

| Scholar | Connection |

| Boyle, Robert

(1627-1691) |

Natural philosopher and proponent of experimental and mechanical philosophy. Key founding member of the Royal Society. The Conway and Boyle families knew each other through their economics and political interests in Ireland. More also knew Boyle through the Hartlib Circle and engaged with him in debate on experimental philosophy. Conway consulted Boyle in 1664 via correspondence on the treatment of her headaches and also scurvy. She was impressed with Boyle’s work and read several of his publications. It is not clear whether she ever met him in person. Some scholars think it is possible that she knew Boyle’s sister Lady Ranelagh, who was close to the Hartlib Circle and active in her brother’s intellectual circles, as well as politics. Lady Ranelagh and Boyle knew Masham and Locke. |

| Cudworth, Ralph

(1617–1688) |

Cambridge Platonist and theologian, Master of Christ’s College, Cambridge. In 1678, he published his work The True Intellectual System of the Universe, which was debated in England and on the Continent by the likes of Pierre Bayle, Jean Le Clerc, and Leibniz. Cudworth was a close friend of More and Conway would have met him in person at Christ’s College and at Ragley Hall. |

| Descartes, René

(1596-1650) |

Philosopher known for his dualist views and critique of Aristotelianism. More corresponded with Descartes in 1648-49, and used his Principia Philosophiae to teach Conway philosophy.

Descartes also corresponded with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, who knew Francis Mercury Van Helmont, the later intellectual companion of Conway. Descartes also knew the Cavendish circle. |

| Elisabeth, Princess of Bohemia

(1618-1680) |