Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta

“The more ignorant a people are, the easier it is for an absolute government to exercise its unlimited power over them. It is based on this principle, so contrary to the progressive march of civilization, that most men oppose women’s access to the means of cultivating their spirits. However, this is a mistake that has been and always will be fatal to the prosperity of nations, as well as to the domestic happiness of man.” (Opúsculo humanitário, 51)

Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta is the pseudonym of Dionísia Gonçalves Pinto. Floresta was a pioneer in Brazilian feminism, having been the major force behind a foundational text on women’s rights in Latin America: Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (The rights of women and the injustice of men). Floresta was also a public intellectual who achieved international recognition during her lifetime. Her work extends well beyond this translation (made in 1832 when she was only 22 years of age) and includes poetry, travel writings, and philosophical essays on morality and education. Most of these works have autobiographical content and are concerned with female virtues and moral upbringing. While the majority of Floresta’s works are in Portuguese, she also wrote in French and Italian, and some of her works were translated to English, Italian, and French during her lifetime, ensuring that her ideas circulated well beyond Brazil.

Newspapers and the Brazilian press were receptive to her writings, and she was known for her activity as a school director (though the post-colonial Brazilian elite did not approve of this work). In 1849 Floresta published the poem A lágrima de um Caeté (The tear of a Caeté), depicting the social conditions of the indigenous group Caeté and the Praieira Revolt. The chapters of her central work, the Opúsculo humanitário (Humanitarian booklet) were disseminated widely in Rio newspapers, and published together as a book in 1853. This work was ahead of its time in many respects, in that it protested the treatment of women, enslaved persons, and indigenous peoples under the colonial regime of 19th century Brazil.

| Preferred citation and a full list of contributors to this entry can be found on the Citation & Credits page. |

1. Biography

Floresta was born October 12, 1810, the daughter of a Portuguese lawyer living in the Province of Papari, in the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. Her life was marked by regional uprisings. In 1817 her family had to leave their Floresta estate (hence her pseudonym) due to the anti-colonial events called the Pernambucan Revolt. After the revolt, her family returned to their land and soon thereafter Brazil became an independent nation. In the following year, in 1823, at the age of thirteen, Floresta married Manuel Alexandre Soabra de Melo, owner of a large local estate and member of an important family of the region. The marriage was unsuccessful, and she soon returned to her family household—oral history indicates that she suffered from an abusive husband and was charged with household abandonment. In 1824, Floresta and her family moved to the city of Olinda in the state of Pernambuco, where they again encountered a turbulent political environment due to the Confederation of Equator, a republican popular uprising. In 1828, Floresta’s father was assassinated, a loss that greatly affected her. Her 1878 posthumously published autobiographical essay, Fragmentos de uma obra inédita (Fragments of an unpublished work), described the loss of her father as well as the unrest that led her family to permanently leave the state of Pernambuco:

“A crowd of uncontrolled men – which we would call a “soft patrol” – strolled around, shooting over the houses; a rifle discharge, crossing the external door of the living room where the young Brasil was laying, fell ten centimeters above the head of this child, who was half asleep on the sofa, escaping from death by a miracle. The distress of all the family exposed to such attacks was immense; our father, taken by the horror that these excesses infused in him and seeing his beautiful property devastated, once so admired by everyone that he would host with the most hospitable welcome, was determined with regret to abandon it.” (translated excerpt, 48-49)

While in Olinda, Floresta met and married Manuel Augusto de Faria Rocha, a young student at the Faculty of Law of Olinda—a central institution in the formation and development of the Brazilian philosophical tradition. Floresta and Manuel Augusto had two children together, Lívia (1830) and Augusto Américo (1833). After Manuel Augusto graduated, they moved to Porto Alegre city, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in 1832. Shortly thereafter, Manuel Augusto died, and Floresta had to support herself and her two young children on her own.

After teaching out of her home, Floresta opened a small school called Colégio Brasil and started her journey as schoolteacher and director in Porto Alegre. At the start of the Ragamuffin Revolt (1835-1845), Floresta and her family moved to the city of Rio de Janeiro, capital of the Brazilian Empire at the time, once again trying to find a stable place to live. There, in 1838, she created and directed a school for girls, the Colégio Augusto, where History, Mathematics and Latin were taught. Teaching these subjects to women was considered scandalous at that time; a newspaper in 1847 published a condemnation of the school curriculum as well as Floresta’s judgment: (Floresta is referred to as “Ms. Augusta” and “Ms. Floresta”)

“There are educational houses that have the bad taste of teaching young girls to make dresses or shirts. Yet it seems that Ms. Augusta thinks this is very prosaic. She teaches them Latin.… We shall note only that Ms. Floresta forgets the true end of education, which is to acquire useful knowledge, and not to overcome difficulties without any real utility.” (translated excerpt, O Mercantil, 17 January 1847)

Despite such objections, the school remained open for 18 years, and during this time Floresta penned various educational writings, such as Conselhos à minha filha (Advice to my daughter) (1845) and the fictions Daciz ou uma jovem completa (Daciz, or A complete young woman) (1847) and Fanny (1847). Also in 1847, she published a lecture, the Discurso que às suas educandas dirigiu Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta (Speech given to her students by Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta), in which she wrote:

“My dear students! (…) Happy are those girls who, having, as you do, parents that worry about your future happiness, further the means to cultivate your spirit, and having [as you do] lessons that tend to perfect your spirits, know how to enjoy the precious study time and make good use of the instruction that our sex so much needs” (translated excerpt, 3-4)

Several years later, in 1853, she published a work on her philosophy of education, the Opúsculo humanitário (Humanitarian booklet).

Beginning in the 1850s, Floresta travelled to Europe and made critical intellectual connections. In 1851, she traveled to France, where she met Auguste Comte and Lamartine and regularly attended Comte’s General History of Humanity Course at the Palais Cardinal. Following a trip back to Brazil in 1852 to resume her teaching duties, Floresta returned to France in 1855 and started to publish in French and Italian. She traveled to Italy, England, Greece, France, Germany, and Portugal.

Floresta participated in French salons—thereby beginning her friendship with important thinkers of that time—and founded a society where there was more public space for women. In 1856, her correspondence with Comte began. He regularly visited her home in Paris, both at 11 Rue d’Enfer and at 9 Rue Royer Collard. Their friendship lasted until his death in 1857. Floresta also connected with Almeida Garret, Alexandro Herculano, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and others. She lived in France for most of this time. Following the collapse of Napoleon III’s empire and the rise of the short-lived revolutionary government of the Paris Commune, Floresta left Paris.

After a few years of traveling, including a brief visit to Brazil, Floresta returned to Europe. She resided in London, Berlin, Lisbon, and Paris, but her final place of residence was Rouen. In 1885, Floresta died of pneumonia and was buried in a cemetery in Bonsecours, France, near the city of Rouen. She was 75 years old.

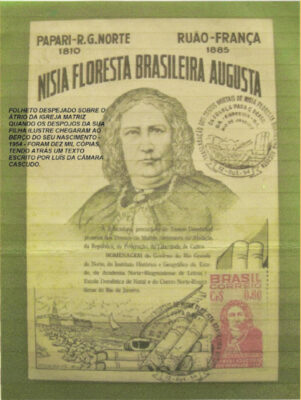

In 1948, the city in which Floresta was born in Rio Grande do Norte, Papari, was renamed in her honor as the City of Nísia Floresta. An indigenous area in Pernambuco was also named after her. In 1954, her remains were returned to Brazil and she was reburied in her hometown. A commemorative seal and stamp were produced by the government and an official celebration took place on 11 September 1954.

References

Augusta, Nísia Floresta Brasileira. (1878) 2001. Fragmentos de uma obra inedita: notas biográficas. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília.

Augusta, Nísia Floresta Brasileira. (1847) 1987. Discurso que às suas educandas dirigiu Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta. Rio de Janeiro: Collegio Augusto.

Duarte, Constância Lima. 2019. #NísiaFlorestaPresente: uma brasileira ilustre. Natal, RN: Mariana Hardi.

Duarte, Constância Lima. 1995. Nísia Floresta: Vida e obra. Natal, RN: UFRN, Editora Universitária.

- “Instrucção Publica: Revista dos Colegios da Capital.” O Mercantil. Sunday, January 17, 1847: 3. Available here.

1.1 Portraits

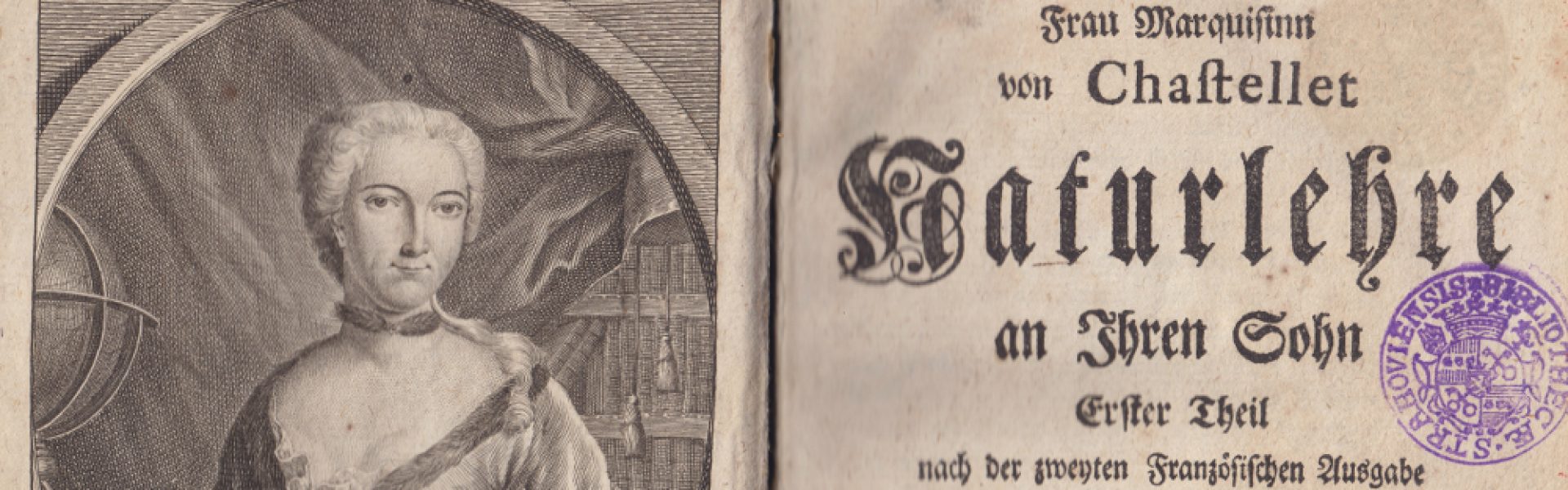

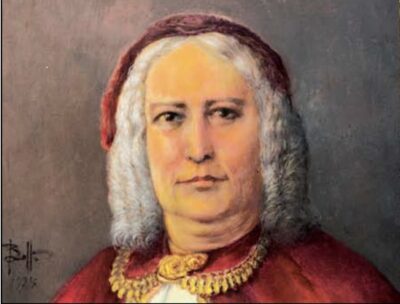

There are many images of Floresta’s works available, from facsimiles of her newspaper articles to first editions that have been digitized. Although there are various kinds of materials from the 19th-century press, much of the 21st-century material attributed to Floresta is not reliable—for example, there are misattributions of images and confusing biographical information.

One of the most recognizable depictions of Floresta appeared in an article about her life and works, and apparently, it was originally a photograph. On 23 May 1872, the New-York-based Portuguese magazine O Novo Mundo published an article entitled D. Nisia Floresta with a large picture of her in the center of the page. (A facsimile of this article can be accessed through the Hemeroteca Digital, the digital division of the National Library of Brazil.)

The image bears the caption “D. Nisia Floresta, Escriptora Brazileira” and the name of the artist (possibly “E. Sears”) along the lower left side of the oval frame. The article ends with a reference to this image: “O retracto que publicamos é tirado de uma photographia ja muito indistincta” (“The portrait we publish was taken from an already very indistinct photography [sic]” (p.133). This depiction of Floresta—facing forward, a collared and fringed jacket over her buttoned shirt and fastened at her neck, her countenance conveying ease and confidence—has been copied many times and is one of the most recognizable presentations of Floresta. For example, a version was used in the celebratory stamp produced by the Brazilian Post Office when Nísia Floresta’s remains were transferred from the Bonsecours cemetery in France to Brazil in 1954. On this occasion, a celebratory pamphlet was also produced and circulated in the city of Nísia Floresta during her reburial ceremony.

Later, the Brazilian visual artist Balthasar da Câmara (1890-1982) painted a posthumous portrait in 1977 based on the same image. This color portrait is located today in the Honor Gallery of the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation in Recife.

An undated photograph of Floresta can be found at the Maison Auguste Comte in Paris, France. No information of its origins is available at present.

1.2 Chronology

| Date | Event |

| 12 October 1810 | Dionísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta, a.k.a. Nísia Floresta, is born on October 12th at “Sítio Floresta,” in Papari, Rio Grande do Norte, to father Dionísio Gonçalves Pinto Lisboa, a Portuguese Lawyer, and mother Antônia Clara Freire |

| 1822 | Brazil’s independence from Portugal is declared by Prince Pedro on September 7, establishing the Empire of Brazil |

| 1828 | Floresta’s father is assassinated by political enemies |

| 1832 | Floresta publishes her first book, Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens |

| 1837 | Floresta, now a widow, moves her family to Rio de Janeiro to escape the Farroupilha Revolt |

| 1838 | Floresta establishes her school, at which she will teach until her move to Europe |

| 1842 | Floresta publishes Conselhos a minha filha |

| 1849 | Floresta publishes A lágrima de um Caeté and moves to Europe |

| 1850 | Trading enslaved people is forbidden in Brazil |

| 1851 | Floresta attends Auguste Comte’s lectures at the Palais Cardinal and visits Alphonse de Lamartine in Paris; she also travels to Portugal |

| 1853 | Floresta publishes her treatment of the place of women in society, Opúsculo humanitário |

| 1856 | Floresta publishes the short story “O pranto filial” and her “Pensamentos.” Her school closes its doors after 18 years. Floresta’s visits and epistolary exchange with Comte continue, until his death the following year. |

| 1858 | Floresta translates her own “Conselhos a minha filha” into Italian and travels extensively in Italy |

| 1871 | In Brazil, the Rio Branco Law, or Law of Free Birth, passes. The law frees all children born to enslaved parents. |

| 1871 | Floresta leaves Paris and returns to Rio de Janeiro |

| 1875 | Floresta returns to Europe on March 24. She first visits her daughter in England, then goes to Lisbon. Floresta’s brother dies on November 9, in Rio de Janeiro. |

| 1878 | Floresta moves to Rouen, France. Her last work, “Fragments d’un ouvrage inédit – Notes biographiques,” is published in Paris. |

| 1885 | Floresta dies on April 24, 1885 in Rouen, France, of pneumonia, at the age of 74. She is buried at Bonsecours Cemetary. |

| 1888 | The Republic is established in Brazil and slavery is abolished. |

| 1954 | Floresta’s home town, Papari, changes its name to “Nisia Floresta City” on September 12. Her remains are repatriated, and buried on the family’s farm, “Sítio Floresta.” |

2. Primary Sources Guide

The majority of Floresta’s works are in Portuguese, but she also wrote in French and Italian. Of the fifteen books published, nine of them were written in Portuguese (one translated to both Italian and French when she was still alive), two in Italian (one translated to English and another translated to French when she was still alive), and four in French. Only one essay was translated into English, Woman, originally written in Italian with the title La Donna. That essay was translated by her daughter Lívia and published in London in 1865.

2.1 Primary Sources

Floresta, Nísia. 1849. A lágrima de um caeté. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de L. A. F. Menezes.

_____. 1832. Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens. Recife: Typographia Fidedigma.

_____. 1833. Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens. 2. ed. Porto Alegre: Typographia de V. F. Andrade.

_____. 1839. Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: n.p.

_____. 1842. Conselhos à minha filha. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de J. S. Cabral

_____. 1847. Daciz ou a jovem completa: historieta oferecida a suas educandas. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de F. Paula Brito.

_____. 1847. Discurso que às suas educandas dirigiu Nísia Floresta. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia Imparcial de F. Paula Brito.

_____. 1847. Fany ou o modelo das donzelas. Rio de Janeiro: Edição do Colégio Augusto

_____. 1849. A lágrima de um caeté. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de L. A. F. Menezes.

_____. 1850. Dedicação de uma amiga. Niterói: Typographia Fluminense de Lopes & Cia. 2. vol.

_____. 1853. Opúsculo humanitário. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de M. A. Silva Lima.

_____. 1854. Páginas de uma vida obscura; Um passeio ao Aqueduto da Carioca; O pranto filial. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia N. Lobo Vianna.

_____. 1855. “Páginas de uma vida obscura.” O Brasil Ilustrado. Rio de Janeiro. January-June, 1855. Available here.

_____. 1855. “Um Improviso, na manhã de 1. Do Corrente, ao distinto literato e grande poeta António Feliciano de castilho”. O Brasil Ilustrado, Rio de Janeiro, April 30, 1855: 157.

_____. 1855. “Passeio ao aqueduto da carioca.“ O Brasil Ilustrado, Rio De Janeiro, July 15, 1855: 68-70.

_____. 1856. “O pranto filial“ O Brasil Ilustrado, Rio de Janeiro, March 31, 1856: 141-2.

_____. 1857. Itineraire d’un voyage en Allemagne. Paris: Firmin Diderot Frères et Cie.

_____. 1858. Consigli a mia figlia. Firenze: Stamperia Sulle Logge del Grano.

_____. 1859. Conseils à ma fille. Translated from Italian by B.D.B. Florence: Le Monnier.

_____. 1859. Conselhos à minha filha, com 40 pensamentos em versos. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de F. Paula Brito.

_____. 1859. Scintille d’un anima brasiliana. Firenze: Tipografia Barbera, Bianchi & C.

_____. 1859. Consigli a mia figlia. 2. ed. Mandovi: n.p.

_____. 1860. Le lagrime d’un Caeté. Translated by Ettore Marcucci. Firenze: Le Monnier.

____. 1864. Trois ans en Italie, auivis d’un voyage en Grèce. Paris: Libraire E. Dentu, vol. 1.

_____. 1865. Woman. Translated by Livia A. de Faria. London: G. Parker.

_____. 1871. Le Brésil. Paris: Libraire André Sagnier.

_____. 1872. Trois ans en Italie, suivis d’un voyage en Grèce. Paris: E. Dentu Libraire- Éditeur et Jeffes, Libraire A. London, vol. 2.

_____. 1878. Fragments d’un ouvrage inédit: notes biographiques. Paris: A. Chérié Editeur.

2.2 Posthumous Editions Of Floresta’s Works

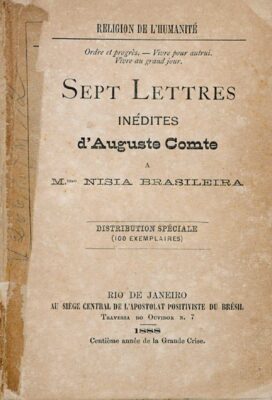

______. 1888. Sete cartas inéditas de Auguste Comte a Nísia Floresta. Rio de Janeiro: Centro do Apostolado do Brasil.

_____. 1888. Sept lettres inédites d’Auguste Comte à Mme. Nísia Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Apostolat Positiviste du Brésil.

______. 1929. Auguste Comte et Mme. Nísia Brasileira: correspondance. Paris: Libraire Albert Blanchard.

______. 1935. Fanny ou o modelo das donzelas. In Mulheres farroupilhas by Fernando Osório. Porto Alegre: Globo.

______. 1938. A Lágrima de um Caeté. Apres. Modesto de Abreu. Revista das Academias de Letras, Rio De Janeiro.

______. 1982. Itinerário de uma viagem à Alemanha. Translated by Francisco Das Chagas Pereira. Natal: Ed. Ufrn.

______. 1989. Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens. 4. ed. Introduction, notes, and afterword by Constância Lima Duarte. São Paulo: Cortez.

______. 1989. Opúsculo humanitário. 2. ed. Introduction and notes by Peggy Sharpe-Valladares. Afterword by Constância Lima Duarte. São Paulo: Cortez.

______. 1997. Cintilações de uma Alma Brasileira. Translated by Michelle Vartulli. Introduction and biographical notes by Constância Lima Duarte. Florianópolis: Mulheres/Santa Cruz do Sul: Edunisc.

______. 1997. A Lágrima de um Caeté. Study and notes by Constância Lima Duarte. Natal: Fundação José Augusto.

______. 1998. Três anos na Itália. Volume I. Translated by Francisco Das Chagas Pereira. Afterword by Constância Lima Duarte. Natal: Ed. Ufrn.

______. 1998. Itinerário de uma viagem à Alemanha. 2. ed. Translated by Francisco Das Chagas Pereira. Study and biographical notes by Constância Lima Duarte. Florianópolis: Mulheres/Santa Cruz Do Sul: Edunisc.

______. 2001. Fragmentos de uma obra inédita. Translated by Nathalie Bernardo Da Câmara. Apres. Constância Lima Duarte. Brasília: Ed. Unb.

______. 2002. Cartas de Nísia Floresta et Auguste Comte. Translated by Miguel Lemos and Paula Berinson. Organization and notes by Constância Lima Duarte. Florianópolis: Mulheres/Santa Cruz Do Sul: Edunisc.

_____. 2019. Cinco obras completas. Sérgio Barcelos Ximenes. Kindle Editions.

______. 2021. Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens. Study and notes by Constância Lima Duarte. Rio Grande do Norte: Sertão das Letras Editora.

_____. 2021. Opúsculo humanitário. Introduction and commentary by Constância Lima Duarte. São Paulo; Editora Blimunda.

______. 2021. A Lágrima de um caeté. Afterword and notes by Constância Lima Duarte. Mossoró: Sarau Das Letras Editora.

2.3 Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (1832)

Nísia Floresta published her first work in Brazil, titled Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (The rights of women and the injustice of men), in 1832. Floresta presented the text as a Portuguese translation of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Floresta herself thought she was translating Wollstonecraft’s work and attributed authorship of the work to “Mistress Godwin”—using what she took to be Wollstonecraft’s married name. But in fact, Direitos is a translation into Portuguese of a French translation of an anonymous English pamphlet written by “Sophia, a Person of Quality.” The original pamphlet was entitled Woman Not Inferior to Man (1739). See Botting and Matthews (2014) for more information on this history.

2.4 A lágrima de um Caeté (1849)

A lágrima de um Caeté (The tear of a Caeté) was published in Rio de Janeiro in 1849 and saw two editions in the very same year—an indication it was widely read. It is a poem of 712 lines, in which Floresta brings together the two major trends in Brazilian romanticism: (1) Indigenous struggles and (2) Social issues during the establishment of Brazil as an independent nation. The poem depicts the oppression of the indigenous Caeté people and laments the suppression of the Praieira Revolt, in which liberals in the state of Pernambuco revolted against defenders of the Brazilian Empire. It offers a strong criticism of the effects of colonialism on the young nation and on its indigenous peoples.

2.5 Opúsculo humanitário (1853)

Opúsculo humanitário (Humanitarian booklet) contains Floresta’s educational project and her treatment of the place of women, indigenous, and enslaved peoples in Brazilian colonial and post-colonial society (i.e. during the Brazilian Empire). Initially, the 62 chapters were published individually and serially in newspapers with a wide circulation in Rio de Janeiro (in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro May to April 1853, and in O Liberal 7 July 1853 to 1854 May 21). They were also collected together and published as a book in 1853, also in Rio de Janeiro. The dedication of the book is to her brother, Joaquim Pinto Brasil.

2.6 Páginas de uma vida obscura (1854)

O Brasil Illustrado, Páginas de uma vida obscura (Brazil illustrated: pages from an obscure life) is an abolitionist narrative, authored under the pseudonym “B.A.” The essay was originally published in serialized chapters in the newspaper (from March 14 to June 30, 1854). It was later published as a book, along with two other essays, Um passeio ao aqueduto Carioca (A walk to the Carioca aqueduct) and O pranto filial (The filial lament).

2.7 Woman (1865)

Nísia Floresta’s Woman (La Donna) was originally published in 1859 as part of Scintille d ‘un’ anima Brasiliana, a collection of five travel essays written in Italian for a European audience. In 1865, Floresta’s daughter, Lívia Faria, translated La Donna from Italian to English as a tribute to her mother.

2.8 Educational writings

After the first publication of Direitos, Floresta dedicated her life to being an educator and director of a school for young women. She published three small moral and pedagogical works focused on the education of girls.

The first, Conselhos à minha filha (Advice for my daughter) (1842), was dedicated to her firstborn, Livia, and reiterates the idea that virtue is the only way for women to achieve happiness and social respect. It was later translated into Italian and French. The Italian translation was entitled Consigli a mia Figlia and had two editions: one in 1858 and another in 1859. Floresta discussed the work with the bishop of Mondovi, who loved the text and wanted a new edition to be read by the students at his convent, all young women. The bishop requested that Floresta change her claim that it is the mother, and not a priest, who should listen to the secrets of a young woman’s soul. Floresta convinced the bishop otherwise, and the work was published without any change and recommended by the bishop to be used in Italian schools. The French translation had only one edition called Conseils á ma fille (1859).

The second work, Fanny, ou o modelo das donzelas (Fanny, or the model of the maidens) (1847), has a heroine who is a model of both female and student virtue. Floresta contrasts Fanny’s dedication with the idleness of other girls, who after leaving school never read a book, fooling themselves that they have gained “something they call freedom.” The work also links education with maternal duties by portraying Fanny as someone who helps her mother with the “burden of housework,” which can bestow on a woman the noblest title of a “good mother of a family.”

The third work, Daciz ou a jovem completa (Daciz, or the complete young woman) (1847), is now lost.

This trilogy was followed by Discurso às educandas (Speech to students) (1847), in which she provides an end-of-school-year message to her students and their families. In 1850, Floresta published Dedicação de uma amiga (A friend’s dedication), the beginning parts of a novel, but only two of an anticipated four volumes were published. Floresta’s last educational work is the Opúsculo humanitário (1853), presented above.

Um improviso (An improvisation) (1855) is a poem published in the press dedicated to the “distinguished literate and great poet, Antônio Feliciano de Castilho,” a Portuguese poet who created his own educational method.

Scintille d’un’anima Brasiliana (Sparks of a Brazilian soul) (1859) was originally published in Florence, Italy, and was translated into Portuguese only in 1997. It is a compilation of short essays. In the first chapter, O Brasil, Floresta attempts to change Europeans’ concept of Brazil, as she discusses the natural wealth, potential, and history of her nation.

In O abismo sob as flores da civilização (The abyss under the flowers of civilization), the short narrative aims to alert youth to the social dangers of modernity.

In Viagem imagética (Imagery travel), once again, Floresta takes her reader to her country of origin, talking about Brazilian nature and, finally, in Um passeio ao jardim de Luxemburgo (A stroll to the Luxembourg gardens), Floresta engages directly with Auguste Comte, discussing education and comparing the American and European spirit.

Floresta’s last educational text, Parsis (1867), is now lost.

2.9 Travel writings

Travel writings were common during the 18th and 19th centuries, and Floresta was familiar with the genre. Visitors from other countries would visit Brazil and write about their impressions of its customs, architecture, culture, and the blended identity created from the influence of both indigenous peoples and colonizers. Floresta used the same form of writing but changed its content. She compared Brazilian and European society, bringing her perspective of the New World to criticize the Old. The cultures she described and analyzed in her travel writings were the German, Italian, Greek, in addition to the Brazilian. Although she considered the Old World to be, in some respects, an example for Brazil, she wrote about it impartially.

Her first piece of travel writing was Itinéraire d’un voyage en Allemagne (Itinerary of a trip to Germany) (1857). Written in the form of correspondence, Itinéraire mixes daydreaming and reality, making the book historically rich and personal at the same time.

Her second work mentions her three-year-stay in Italy and a trip to Greece, as the title implies: Trois ans en Italie: suivis d’un voyage en Grèce (Three years in Italy: followed by a trip to Greece) (1864). The book is a critical reflection on the social and political transformation that Italy was undergoing with its revolutions. She employs historical data to analyze the political development of Italy as a nation. In a sense, the work foresees the Italian Unification. Her writing was diverse: she wrote letters, journals, confessions, and chronicles to try to get to know the way of life, history, and cultural manifestations of the Italian people. In addition, her work is in dialogue with other accounts of Italy written by Byron, Goethe, and Madame de Staël.

Finally, in Um passeio ao aqueduto Carioca (A walk to the Carioca aqueduct) (1855), Floresta introduces the city of Rio de Janeiro to foreigners by describing the city’s most famous attractions. Despite showing her love for her country, Floresta acknowledges its defects.

2.10 Autobiographical works

O pranto filial (The filial lament) (1856) was published in a newspaper in Rio de Janeiro upon the death of Antônia Clara Freire, Nísia Floresta’s mother. Through this text, one can perceive the enormous void that her mother’s passing leaves in Floresta’s life; there are also passages about how life became complicated after the death of her father and how her mother’s presence was a foundation for her family. After this event, Floresta was very shaken and moved to Europe in search of new vistas.

Fragments d’un ouvrage inédit: notes biographiques (Fragments of an unpublished work: biographical notes), was the last book that Floresta published. When her brother Joaquim Pinto Brazil died in 1875, Floresta found herself in England and, to honor him, she wrote a work that spoke about her years in her homeland, where her brother was present. Although the work was thought of as a tribute to Joaquim, it has autobiographical elements that teach us about Floresta’s childhood and about events that permeated the author’s life. The book reveals Floresta’s effort to teach her brother his first letters, the almost maternal love she felt for him, his childhood in Papari, and the risks the family took due to constant popular struggles against the Portuguese government. In addition to her personal history, it is possible to follow the various separatist attempts of a republican nature that occurred in northeastern Brazil, which the book records in detail. It also contains information about the trips Floresta made in Europe. She provides a testimonial account of events that took place in Paris in the early 1870s, including a portrayal of the desolate situation there after a bombing in the capital. Floresta had soon after fled this situation, selling her belongings and boarding the English steamer Neva for its last season in Brazil.

3. Secondary Sources

Botting, Eileen Hunt. 2013. “Wollstonecraft in Europe, 1792–1904: A Revisionist Reception History.” History of European Ideas 39 (4): 503–27.

_____. 2020. “Nineteenth-Century Critical Reception.” In Mary Wollstonecraft in Context, edited by Nancy E. Johnson and Paul Keen, 50-56. Cambridge University Press.

Botting, Eileen Hunt, and Madeline Cronin. 2014. “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, edited by Eileen Hunt Botting, 315–22. Yale University Press.

Botting, Eileen Hunt, and Charlotte Hammond Matthews. 2014. “Overthrowing the Floresta–Wollstonecraft Myth for Latin American Feminism.” Gender & History 26 (1): 64–83.

Campoi, Isabela Candeloro. 2011. “O Livro ‘Direito das Mulheres e injustiça dos homens’ de Nísia Floresta: Literatura, Mulheres e o Brasil do Século XIX” In História (São Paulo) vol.30, no.2: 196-213.

Castriciano, Henrique. 1908. “Nísia Floresta.” Almanaque brasileiro garnier. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Garnier.

Câmara, Adauto Da. 1938. “À lágrima de um caeté.” Revista das academias de letras. Rio de Janeiro.

_____. 1941. História de Nísia Floresta. Rio de Janeiro: Editores Irmãos Potengi.

Duarte, Constância Lima. 1989. “Introdução. Floresta Brasileira Augusta, Nísia.” In Direitos das mulheres e as injustiças dos homens by Nísia Floresta. São Paulo: Cortez Editora.

_____. 1990. “Nos primórdios do feminismo brasileiro: direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens.” In A mulher na literatura organized by Nádia B. Gotlib. vol. 3: 38-41. Belo Horizonte: Imprensa Da Ufmg.

_____. 1995. Nísia Floresta: vida e obra. Natal: Ed. Ufrn.

_____. 1997. “Le mythe de la maternité en France au XIXe siècle: lecture de La Femme, de Nísia Floresta.” In Les Femmes dans la ille: Un Dialogue Franco-Brésilien edited by Mattoso, Katia de Queiros. Paris: Centre D’études Sur Le Brésil, Presses de l’université de Paris- Sorbonne.

_____. 1999. “Revendo o indianismo brasileiro: A lágrima de um caeté, de Nísia Floresta.” Revista do Centro de Estudos Portugueses, vol. 19, no. 25: 153-177, December, 1999.

______. 2019. #Nísia Floresta Presente: uma brasileira ilustre. Natal: Mariana Hardi.

_____. 2021. “Ainda o Enigma: revendo os primórdios do feminismo brasileiro.” In Floresta Brasileira Augusta, Nísia. Direitos das mulheres e as injustiças dos homens. Natal: Sertão Das Letras Edições.

Fonseca Ferreira, Ligia. 2016. “Itinerário de uma viajante brasileira na Europa: Nísia Floresta (1810-1885).” Revista do Centro de Pesquisa e Formação, no. 3.

Gardeton, César. (1826) (Translator) Les Droits des femmes, et l’injustice des hommes ; par Mistriss Godwin. Traduit Librement de l’Anglais, sur la Huitième Édition ; Augmenté d’un Apologue : L’Instruction sert aux femmes à trouver des maris. par M. César Gardeton, Auteur du Dictionnaire de la beauté, Etc., Etc. Paris, L. F. Hivert, Libraire, Rue des Mathurins Saint-Jacques, N° 18. Available here.

Lima, Oliveira. 1919. Nísia Floresta. Rio de Janeiro, Revista do Brasil.

Lobato, Monteiro. 2003 (1933). “A feminina,” Na Antevéspera Reações Mentais dum Ingênuo. Companhia Editora Nacional: São Paulo. eBooksBrasil.org.

Lucio, Sônia Valéria Marinho. 1999. Uma viajante brasileira na Itália do risorgimento. Tradução comentada do livro Trois ans in Italie suivis d’un voyave en Grèce (vol.I-1864; vol.II – s.d.) de Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta. Phd Thesis. Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

Lins, Ivan. 1964. Nísia Floresta: história do positivismo no Brasil. Cap. Ii. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.

Margutti, Paulo. 2019. Nísia Floresta, uma brasileira desconhecida – feminismo, positivismo e outras tendências. Porto Alegre: Editora Fi.

_____. 2017. “Nísia Floresta e a questão da autoria de Direitos das mulheres, injustiças dos homens.” Annales (2017) vol. 2 no. 3: 5-28.

Matthews, Charlotte H. 2010. “Between ‘Founding Text’ and ‘Literary Prank’: Reasoning the Roots of Nisa Floresta’s Direitos das mulheres e as injustiças dos homens.” Ellipsis 8 (2010): 9-36.

____. 2012. Gender, Race and Patriotism in the Works of Nísia Floresta. Boydell & Brewer.

Osorio, Fernando. 1935. Mulheres farroupilhas. Porto Alegre: Globo.

Pallares-Burke, Maria Lúcia Garcia. 1996. “A Mary Wollstonecraft que o Brasil conheceu, ou a travessura literária de Nísia Floresta.” In Nísia Floresta, O carapuceiro e outros ensaios da tradução cultural, 167-92. S. Paulo: Hucitec.

_____. 2020. “Travessura Revolucionária.” Revista Piauí. October 6th, 2020.

Pereira, Laura Sanches. 2017. Nísia Floresta: memória e história da mulher intelectual oitocentista. Dissertação de mestrado do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sociedade, Cultura e Fronteiras. Orientador Fábio Lopes Alves. Foz do Iguaçu: Universidade do Oeste do Paraná.

Pugliese, Nastassja. 2022. “E as filósofas brasileiras? Esboço de uma história” In Dez mulheres filósofas por Armin Strohmeyr. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Record.

_____. Forthcoming 2023. Nísia Floresta. Cambridge University Press.

Rosa, Graziela Rinaldi da. 2012. Transgressão e moralidade na formação de uma “matrona esclarecida.” Contradições na filosofia de educação nisiana. Tese de doutorado. São Leopoldo: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Unisinos.

Sabino, Ignez. 1899. Mulheres illustres do Brazil. Rio De Janeiro/Paris: H. Garnier.

Seidl, Roberto. 1933. Nísia Floresta: 1810-1885. Rio De Janeiro: n.p.

Sharpe, Peggy. 1989. “Introdução.” In Opúsculo Humanitário por Nísia Floresta. Edição atualizada com estudo introdutório e notas de Peggy Sharpe-Valadares. S. Paulo: Cortez Editora.

Sharpe, Peggy, and Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta. 1995. “Nísia Floresta: ‘Woman’ (Including Livia A. de Faria’s English Translation of Floresta’s Essay).” In Brasil/Brazil: A Journal Of Brazilian Literature, 83-120. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library.

Simon-Martin, Meritxell. 2022. “The Inverted Mirror: Brazilian Hybridity and European Picturesqueness in Nísia Floresta’s Travel Writing.” In Gender Historical and Postcolonial Perspectives on Journeys, edited by Lilli Riettiens and Elke Kleinau, 83–112. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

Sophia, and Marguerite B. Hicks. 1739. Woman Not Inferior to Man, or, A Short and Modest Vindication of the Natural Right of the Fair-Sex to a Perfect Equality of Power, Dignity, and Esteem, with the Men / by Sophia, a Person of Quality. London: Printed for J. Hawkins.

Strohmeyr, Armin. 2022. Dez mulheres filósofas e coma suas ideias marcaram o mundo. 1A edição ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Record.

4. Philosophy & Teaching

4.1 On Floresta’s Methodology

Floresta’s arguments in her various works aim to establish the virtues and capabilities of women. But she deploys different methods to establish this conclusion in different works, sometimes using descriptions and sometimes using a more normative tone. Understanding the scope of the conclusion requires attention to the method. Some of Floresta’s work uses cultural comparison as a means to criticize social customs, and builds her critique on the basis of the principle that women’s rationality is complete. Through the analysis of the social habits of different cultures and the place of women in different societies, Floresta constructs a view of women’s virtues and a perspective on the role of women’s education in social development. Additionally, Floresta explicitly says that logic must be employed in social analysis, but she also makes use of rhetorical techniques, which indicates that she perceived a need to shape her discourse to her audience. Floresta also uses literature as a means to teach virtue, writing in the form of romances what she could have written in plain philosophical form. This strategy is employed as a pedagogical choice, as those texts were adopted in her school to be read by young girls. Finally, Floresta also uses biographical narrative as a way to do historiography. When narrating her own experiences, she takes the opportunity to recount the history of the places she has visited and to analyze the historical events that were taking place while she was there.

4.2 Overview of the Content of Floresta’s Major Works

Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens (1832)

This work is a free translation of an early feminist pamphlet by an anonymous author in the 18th century. Floresta’s translation begins with a “Dedication to the Women of Brazil and Brazilian Male Academics.” Hoping that her work would help improve the situation of Brazilian women in society, she wrote:

“I hope that one day, during a free time between the highly important works from the ministry, I hope you will act with justice towards our sex and if you do not make a metamorphosis on the current state of affairs, at least we will find a better luck, that you won’t doubt we are deserving.” (Direitos das mulheres e a injustiça dos homens)

The main text of Direitos uses logic to construct an argument not only for the equal capacity of women, but even for their superiority in the moral domain. Direitos exhibits a radically critical tone toward societal customs and identifies rational deficiencies in men as the causal force behind sexism. The work’s introduction explains the tendencies of men to commit epistemic fallacies and uphold dogmatic beliefs, and asserts that there is no difference between men and women outside of the system men have created. The text’s second and sixth chapters discuss the degree to which women’s responsibilities are esteemed, and they refute both the belief that women’s traditional contributions to society should be devalued and also the belief that women’s natural affinity for their traditional caregiving roles proves them unable to perform any other roles. Chapter Three dismantles the claim of women’s intellectual inferiority, while Chapters Four, Five, and Seven advance arguments for women’s superior ability to govern in political, educational, and even military offices. Direitos’ conclusion reasserts that beliefs in women’s inferiority are not grounded in impartial, rational methods, and that they are thus unjust. The text’s final recommendations do not advocate for revolt or for alteration of the current workings of society. Rather, the author aims to emancipate the minds of women from the irrational belief in their own inferiority and to illuminate the benefits that can be gained for all once equality of the sexes beomes a reality.

A lágrima de um Caeté (1849)

“God who no race made

to have over another

revolting superiority

unlimited power” (A lágrima de um Caeté, 37)

As mentioned in section 2, this poem of 712 lines combines two major strands in Brazilian Romanticism: the struggles of indigenous peoples, and social issues arising within the period of the Brazilian Empire. The Empire occupies the historical period from 1822 to 1888, beginning with Brazil’s independence from Portugal, and ending with the proclamation of the republic. The period was marked by popular uprisings due to the continuing influence of the heirs to the Portuguese crown on the Brazilian economy, as well as social developments within the newly independent nation.

In the story told through the poem, the first protagonist is an unnamed member of the Caeté people, a Brazilian indigenous group, and the oppressor is the Portuguese colonizer, also not named. As the poem moves to its second stage, the antagonists beome the men who represent and defend the Brazilian Empire, and the protagonists are the liberals revolting against it. This second part depicts the recent Praieira Revolt of 1848-9, which took place in the province of Pernambuco. Lágrima is configured as a lament both for the defeat of the indigenous people and for the liberals of Pernambuco. The poem describes how the fate of the indigenous Caeté people—a marginalized group inside Brazil—is a product of European despotism. Floresta denounces the expropriation of indigenous lands and cultures, but also laments the loss of the Brazilian liberals in the revolt. The poem is pessimistic, offering a strong criticism of colonization and its effects.

“To the domination of oppressive tyrants,

That in name of pious heaven came

To take the possessions that heaven bestowed on us

Our wives, our daughter, our peace have stolen from us! …

Bringing from across the ocean the laws, the vices,

putting away our laws and our traditions!” (Floresta 1849, 11)

Opúsculo humanitário (1853)

“It is not its physical constitution … that makes men superior, but intelligence…. And intelligence has no sex.” (Opúsculo humanitário, 63)

In this work, Floresta posits that the measure of a civilization’s progress is the place that women occupy in it. To frame her argument, Floresta uses the first five chapters of Opúsculo to comment on the place of women in both ancient and modern civilizations. In chapters 6-16, she discusses the contemporary situation of four great nations of the mid-19th century (Germany, Great Britain, France, and the United States) in terms of the place of women in those societies:

“After Descartes has opened a new era to philosophy (…), the French women no longer remained limited to the examples of courage given by Joanne of Arc when she had the glory of freeing her fatherland, (….) other virtues, other triumphs, of which women are more deserving, took place, distinguishing the French women of our days.” (Opúsculo humanitário, 31)

In chapters 17-39, Floresta discusses education in Brazil, attributing the backwardness of education in the country to colonization. Finally, in chapters 40 to 62, Floresta weaves in her educational project for Brazilian women. Throughout the book, the influence of classical and early modern philosophy (Plato and Descartes, for example) can be seen, as well as the influence of her Catholic upbringing.

Páginas de uma vida obscura (1854)

In Páginas, Floresta narrates the life of a slave named Domingos who is taken from his nation to be enslaved in Brazil. Even in the face of all his self-denial and his difficulties, he chooses to be virtuous. Floresta describes the institution of slavery using adjectives such as “anti-humanitarian,” “sad,” and “complete abnegation,” and she appeals to Christian morality to defend equality between men ( 9). This narrative was inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, one of the most famous novels in nineteenth-century America. In the opening paragraphs of the essay, Floresta argues for the inversion of the relationship between class and moral worth. That is, with respect to the ability to act with justice, the marginalized class (the enslaved) should be held higher than the nobles and heirs, given that they are more virtuous. For this reason, their actions should be taken as examples for humanity. She writes:

“It is not the brilliant deeds of a genius or the noisy achievements of a warrior that today cause our admiration for a minority, forcing us to write down a couple of lines as means to pay them due tribute.

It is also not the prestige of a name inherited from grandparents, acquired by pounds of gold, or someone high of society due to actions almost always assessed by circumstances more or less favourable, sometimes calculated, by those who seek to ennoble him under the pretence of receiving homages from his contemporaries and the glory in posterity….

It is indeed a life of ordeals, of complete abnegation, of dedication without an example, all submerged under an obscure death! It is the life and death of one of those beings, despised among us, to whom men will make suffer like a martyr and not even church dedicates a prayer after his passing!

Men of all classes, of all beliefs, men who have heart, come with us, kneel down at the grave of a slave to hear his story! Come learn from it the virtues that honor humanity!”

Woman (1865)

Woman can be divided into four sections. In the first section, Floresta uses a first-person narrative to criticize the lack of dignity and equality in the present state of modernity by examining the dire conditions of foster children and mothers in villages outside of Paris. In the second section, Floresta identifies the cause of this injustice: a lack of moral education. She criticizes the misuse of excess wealth and the prevalence of an education for mere illustration in nations that neglect the welfare of their own people. Floresta also identifies ‘self-denial’ as a natural and significant female virtue. In the third section, Floresta argues for the equality of men and women and defends women’s right to an education. Floresta claims that mothers are responsible for providing their children with a moral education and treats motherhood itself as having immense political power. In the final section, Floresta argues that mothers should educate their children with an emphasis on duty and humility. In the conclusion of the text, Floresta reiterates her main argument: that the progress of a truly civilized nation begins with moral education and therefore begins with motherhood. Ultimately, Woman serves as a summation of Floresta’s concerns with women’s rights, the dichotomy of the civilized versus the barbaric, the significance of a moral education, and the role of female virtue.

4.3 Philosophical Themes

The Nature of Reason

In producing persuasive arguments for the equality of the sexes, Floresta demonstrates distinct forms of reasoning throughout her published works. Floresta’s first published text, Direitos das mulheres e injustiça dos homens, was a work she loosely translated. It contains an assessment of the case for gender equality from a Cartesian standpoint. Specifically, the work seems to presuppose a Cartesian metaphysics, according to which each human is a union between the mind, a purely intellectual, rational capacity, and the body. The text conceives of reason as an impartial judge and deploys it to systematically test each claim that men have made about the inferiority of women. And it is structured by the aim of ensuring that our beliefs are justified and founded on reasons. On the basis of these assumptions, she argues that any differences between the sexes are only bodily. When it comes to the mind, Floresta argues, women are as capable as men are to engage in intellectual and non-domestic activities.

Woman seems to move away from these assumptions of universal human rationality, and begins to develop a conception of reason that incorporates the influence of gender. That is, the rationality of our inferences and conclusions has a gendered dimension. In Woman, this gendered dimension to reason is developed through an exploration of the differences between men’s and women’s natures and their roles in society. These differences are reflected in the ways men and women use their reason to make inferences. By incorporating this understanding into our view of reason, we can celebrate the virtues of having two differentiated roles. Cartesian conclusions about the equality of the sexes and their respective intellectual capabilities still apply evenly and equally across the sexes. However, Floresta’s idea of a ‘gendered’ reason will lead to different outcomes based on the sex being considered. Seen through the lens of ‘gendered’ reason, one would conclude that women should fulfill certain roles based on their natural dispositions.

While Direitos stresses the importance of customs, education, and cultural practices as causes of inequality between the sexes, Woman identifies nature as the true cause of gender-based differentiations in culture. Ultimately, Woman makes the normative prescription that, since a woman’s nature inclines her toward the capabilities of the heart, women should seek roles inside of the family home, by providing a good moral education to their children and by being useful in the domestic environment. In searching for a source on which to blame the inequality of the sexes, Direitos identifies the faulty epistemic practices of men as mechanisms by which dogmatic beliefs and logical fallacies continue in a circular system of oppression. But in Woman, Floresta takes a different approach, arguing that the fault lies with the lack of moral education in society. The blame for perpetuating the maltreatment of women is placed on the inertia of bad family examples.

Female Virtues

Early on in Woman (1865), Floresta establishes the importance of the female virtues. To be a woman, Floresta explicitly claims, is to practice virtue. Partially in response to what she perceived as the budding ‘egotism’ of the modern world, Floresta emphasizes virtues such as resignation, modesty, charity, loyalty to one’s family, and obedience, throughout her work. Most importantly, Floresta argues that women naturally possess the noble virtue of generosity or ‘self-denial.’ In their generosity, women direct their attention to the care of others. In doing so, women focus on the wellbeing of their husbands and children and joyfully perform domestic duties. The ‘sublime sacrifice’ of motherhood and the ‘self-abnegation’ natural to women not only serve to nourish the family, but also, according to Floresta, provide women with a route to political agency. Floresta believes that virtues pertaining to the private sphere, such as the care of a mother for her children, can translate into powerful political action. Virtues, for Floresta, are social habits. For this reason, she argues, virtues natural to women are more effective in “healing” the wounds of the modern world than are the intellects of educated men. These men, Floresta argues, ought to value women for their supreme virtue instead of their beauty and to treat them as companions. Although generosity is a natural virtue, women must receive a moral education in order to know how to apply their virtues. In turn, these mothers must provide their own children with a moral education. By doing so, women raise good citizens who recognize the importance of duty, equality, and humility, thus positively influencing the polity. For Floresta, it is through motherhood and their natural virtues that women hold political power and agency. Although this care begins in the home, Floresta believes that female virtues, when encouraged through moral education, can shape the state of a nation.

Education

It is no surprise that much of Floresta’s work centers on education. Not only was Floresta a serious student, she also founded and ran a school in Rio de Janeiro. There, she created opportunities for young women to receive an education that included subjects beyond the domestic arts. Floresta’s curriculum included poetry, geography, ancient and modern history, Latin, Italian and French grammar, and literature, as well as classes that focused on domestic skills. In her philosophy, however, Floresta draws a distinction between institutional academic education and moral education, arguing that girls should receive moral education, a view closely tied to her conception of female virtues. As for institutional academic education, which was dominated by men, Floresta criticizes it for being ineffective in the fight to end inequality in the modern world.

In Woman, Floresta identifies moral education as the proper response to injustices like the neglect of children seen throughout Europe. A moral education serves to refine and engage with the heart as opposed to the mind. An education of the heart nourishes the spiritual well-being of a country both in the private home through parenting and in the public sphere through schooling and government. Floresta believed that women’s hearts were different from the hearts of men and better suited for moral education. With this education in hand, women can combat bodily temptations and egotism. They can also become ‘mother-educators,’ a role natural to women. Through example, the ‘mother-educator’ teaches her children the importance of virtues like duty, resignation, loyalty, and humility. ‘Mother-educators’ have great political agency for Floresta as they shape citizens in raising their children. Floresta argues that in order to disrupt the cycle of oppression of women, daughters and sons must be raised with equal treatment. It is in the household, Floresta argues, that children learn how to understand gender and begin to care for others. As noted above, Floresta does not explicitly argue that women should receive an institutional academic education. In her written works, she puts forth moral education as the most effective way to combat injustice and centers women as crucial to this endeavor. Floresta’s support for equal access to ‘academic’ education is nonetheless clear through her practice. As noted, in her capacities as a school founder and director she encouraged and promoted equal access to both forms of education for girls attending her school.

5. Correspondence

5.1 Letters from Auguste Comte

Auguste Comte was the founder of a philosophy and major 19th century intellectual movement called positivism, which promoted pragmatic political action and empirical science as means of achieving human progress. Positivism had a major influence on the development of the nascent Brazilian nation, which adapted its motto, “Order and Progress,” from Comte’s writings.

Comte and Floresta had an intellectually vibrant exchange, and he once described her as the future of positivism. In 1851, Floresta attended his Course on the General History of Humanity at the Palais Cardinal in Paris (now the Palais-Royal). Floresta visited him at his home and he also paid her visits. In The History of Positivism in Brazil, Ivan Lins provides a description of one of these meetings by a Brazilian man who was present at one of them. The man described Floresta’s house as “the salon of the Brazilian woman writer” (Lins, 21-22), where she would effusively receive Comte upon his arrival. She used to tell those present that Comte was a genius. Floresta was in France when he passed away and was at his funeral paying her last respects. Among all of Floresta’s correspondence, theirs is the best preserved, as well as the first to be published. A limited edition of 100 copies was printed in 1888 in Rio de Janeiro. The publisher was an organization called the Positivist Church and Apostolate of Brazil, founded in 1881 by Brazilian followers of Comte. Due to her proximity to Comte, Floresta has been considered to be a positivist, however, she never became a member of the group. As for the book, it contains 7 letters that Auguste Comte sent to Nísia Floresta, but does not contain any of her replies. In Comte’s letters, the theme of having a female intellectual friend recurs throughout. He writes that having such worthy female companions helps in intellectual work, as “only they can dissipate or correct the fatal dryness of theorizing” (p. 6). Comte addresses her as “Madame Brasileira,” or “Brazilian Madame,” an indication that she was known in intellectual circles as the Brazilian female intellectual of the time.

5.2 Letters to George Duvernoy

George Duvernoy was a French naturalist, zoologist, and professor at the Collège de France. He and Floresta were close friends and Duvernoy welcomed Floresta to his courses. Their families were close as well, and gathered in Paris to spend time together. Archival research conducted by Professor Monalisa Carrilho has revealed that two letters that Floresta sent to Duvernoy are housed in the archives of the Museum of Natural History of France in Paris. We do not have Duvernoy’s letters to Floresta.

Floresta’s first letter is dated 13 August 1852, written from Rio de Janeiro. At the time, Floresta had recently arrived in Brazil after her first period of travel in Europe (1849 – 1851). Her letter has an affectionate tone, and is written in reply to an earlier letter from Duvernoy. She thanks him for the time they spent with their families together in Paris and expresses her worry about his health. She wishes him well, reprimanding him for continuing to teach a class even when facing a pulmonary illness. Her well-meaning reprimand is accompanied by a statement of her views on the labor involved in doing science, both as an individual and as a society, and she uses the occasion to talk about the conditions of education in Brazil:

“In spite of your weakened lungs, you insist on continuing to teach. My God, how beautiful and powerful is the love for science, since it makes us forget all material concerns about our own preservation. I wish I could reprehend my wise friend for his excessive self-denial, which only threatens to remove him prematurely from his friends. And yet, I am dying to imitate him in the narrow sphere of my intelligence by dedicating myself, as I have done, to studies on education in my country, where it is still so difficult to achieve the degree of perfection that I dream for it.”

Floresta then mentions having published the Opúsculo humanitário, and expresses a wish to translate it into French so that she could offer him a volume. She thanks him for the courses she attended and wishes him a quick recovery so they can continue their intellectual exchange. At this time, Duvernoy was about to turn 76 years old. She reprimands him again, saying that it is his love for science that is killing him. In the letter we also have information about Floresta acting as a collector of specimens for Duvernoy. She tells him that she has some Brazilian insects to give him, but does not know how to send them without damaging the specimens. The letter is signed “Brasileira,” indicating that she is known for being the “Brazilian woman” within French intellectual circles.

There is also a second letter from 24 March 1855, written after Duvernoy’s passing. She did not know about his death at that time, and wrote this letter after he passed away on March 1, 1855.

As of the time of this entry’s publication, Professor Carrilho (who discovered these letters) is still in the process of transcribing and translating them for publication. The information we have on the content of the letters is the result of a reading she prepared for Professors Nastassja Pugliese and Gisele Secco in December 2022, which was recorded and used as the source here.

5.3 Lost letters

In her autobiographical works and travel diaries, Floresta describes her interactions with European intellectuals from various backgrounds—philosophers, historians, literary figures, musicians, members of the church, and state officials. She corresponded with a good number of them, including the French writers Alexander Dumas, Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine, George Sand, Auguste de Saint Hilaire, and the Italians Anita and Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazinni, activists in the Risorgimento movement concerning the unification of Italy. Locating the collected correspondence of Floresta remains an open problem for researchers. According to Duarte, Floresta’s major biographer, Floresta’s letters were lost on a shipwreck when her daughter Lívia sent them from Paris to Rio for publication in Brazil (Conversation with Prof. Pugliese and Yasmim Pontes for this entry). Nevertheless, some letters are probably still scattered in the collected correspondence of the recipients, as in the case of George Duvernoy. Looking for these letters and collecting them is an open task for archival research.

6. Connections

6.1 Poulain, Sophia, and Wollstonecraft

To understand the relationship between Floresta and other thinkers, it is important to keep in mind that these relationships were often through translation, which in the early modern period allowed the translator much more liberty to interpret the text than we are accustomed to today. As research on Floresta continues, we will come to understand more about her own perceptions of what she was reading and what she intended in her translations of other works.

Floresta’s Direitos is a translation of the anonymous work of someone called only “Sophia.” This first Sophia pamphlet is itself a reworking of Cartesian arguments contained in François Poulain de la Barre’s On the Equality of the Sexes (see Clarke 2013, 9-13), first published in 1673. Poulain’s work defending the equality of men and women circulated widely in French, was translated into English in 1677, and later became the basis for Sophia’s text, Woman not inferior to man, published in London in 1739. Complicating the matter further, Direitos was considered for a long time to instead be a translation of Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman. These complex circumstances may have made it harder to appreciate the differences Floresta perceived between her project and Wollstonecraft’s. For instance, when citing Wollstonecraft in the Opúsculo humanitário, Floresta distinguishes her aims from those of the English philosopher. Floresta says she is not actively engaged in the defense of women’s rights like Wollstonecraft. Instead, her interests lay in fighting for the quality of women’s education. She writes: “But let’s leave to Wollstonecraft, Condorcet, Sièyés, Legouvé, etc. the defense of the rights of the sex. Our task is a different one and, we believe, more suitable to modern societies: the education of women.” Due to these historical and textual complexities, Direitos connects Floresta with Poulain, Sophia and Wollstonecraft in different ways and for different reasons (for more information see Pugliese 2023).

6.2 De Stäel, Descartes, Plato, Rousseau, Fénelon

Floresta was a voracious reader. Many of her works contain bibliographic information from which we can surmise the wide range of texts that she read. For example, aside from proposing a new educational project for Brazilian girls, Opúsculo humanitário shows us that Floresta consulted many authors throughout her life. Even a casual reader will notice numerous quotations—direct and indirect—from canonical authors of her time.

However, it is clear that some authors served as particular inspiration for Floresta in her philosophical formation. François Fénelon is cited as a wise man in her Opúsculo and as “sublime” in a speech that Floresta gave to her pupils at the end of the 1847 school year. Madame de Staël’s name appears in her works with many complimentary adjectives—“illustrious author,” “transcendent talent,” etc. Floresta’s connection with Madame de Staël is not limited to her admiration of Staël’s works: Floresta was considered by many to be the “Brazilian Madame de Staël.” Like Staël, she also wrote travel diaries, considered Descartes as a central figure for the conquest of women’s rights, and took Plato as her metaphysical reference. She also criticized Rousseau for his views on the education of women. Here are some examples of her citations of these authors.

“Woman is like man, just as the sublime Plato expresses, a soul making use of a body” (Opúsculo, 62)

“The virtuous Montesquieu, thinking about woman in this way, was authorizing the degenerate spiritualist Rousseau when said: ‘Woman is made especially to please the man; if man must please in his turn, it is less directly necessary; his merit lies in his power, he pleases for this alone: he is strong.’” (Opúsculo, 32)

“The sublime Fenelon understood well this happiness when he said: ‘The ignorance of a lady is the cause of the state in which she often finds herself, the state of indefinite boredom of the world, due to which they – innocently – don’t know how to use their time.’” (Discurso, 6)

“One of the two premier French writers of our century, Mme. De Staël, ascribes the easiness of divorce among Germans to the introduction of a certain sort of anarchy into families, that allows nothing to survive in its truth and in its strength.” (Opúsculo, 25)

6.3 Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Beecher Stowe was a 19th century author and abolitionist. Stowe is best known for Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), a novel depicting the horrors of slavery in America, which is sometimes credited as helping to foment the American Civil War. The book is centered on the importance of Christian values and takes slavery to be at odds with Christian doctrine. In Opúsculo, Floresta praises Stowe and encourages her audience to read her texts. Stowe’s influence on Floresta is seen most clearly in Floresta’s Páginas de uma vida obscura (1854) (Pages from an obscure life). Páginas tells the story of a slave named Domingos. Similar to Stowe, Floresta emphasizes the hypocrisy of cruel Christian slave owners and esteems Domingos for upholding his Christian virtues in the face of oppression.

“Mrs. Stowe’s book is a moral primer of delicate style, of sublime sentiments, (…) demonstrating crimes in the presence of their victims in ways that are best able to inspire interest and compassion, under the cry of strict morality that severely accuses societies of any nations who have committed those crimes” Opúsculo humanitário, 42

“We, Brazilians who read this book, ashamed of the same disgrace that also weighs over our land, ashamed of the reproductions of the scenes of horror that are described with such pathos by the distinguished Stowe, we should make our children memorize some of its most outstanding pages so that we can remain hopeful that future generations will erase, for those who will one day read our story, the painful impression left by the crimes committed by present generations against the unfortunate African race.” Opúsculo humanitário, 42

6.4 Monteiro Lobato and Gilberto Freyre

Nísia Floresta became known as a great Brazilian intellectual who never received as much attention as she deserved. In the early 20th century, the Brazilian writer Monteiro Lobato gave Floresta as an example of a poet whose work it was important to recover, but who would likely end up being forgotten once again. Gilberto Freyre, the Brazilian sociologist, also cites her as an example of an exceptional woman. Various other important Brazilian authors cited her work, including Luis da Camara Cascudo and Raquel de Queiroz.

Monteiro Lobato (1882-1948) is a famous writer in Brazil who has recently been subjected to fierce criticism on account of his explicit racism. Lobato’s book collection, O sítio do pica-pau amarelo (The yellow woodpecker farm), has been read by children in Brazil for decades. Today, there is a discussion on whether these books should continue to be read in schools. In his short story The feminine, Lobato imagines—in an ironic but still misogynist description—what the construction of a Female Academy of Letters would look like. It was prohibited for women to participate in the Brazilian Academy of Letters, but instead of discussing the prohibition in his short story, he instead imagines the construction of the female version of the Academy. The quotation’s explicit racism and misogyny serves to illustrate attitudes still prevailing in early 20th century Brazil.

“Structured on this basis, the new academy will have a long and pleasant lifetime. Our ladies will meet every week to chat about fashion, social events, weddings, divorces, etc., before the session. During the session one will read verses from forgotten poetesses, such as Nísia Floresta; another will discourse on the absurd design of the Chinese shoes, another will say thundering words on the traffic of white women; and another will prove that human intelligence has no sex.

Once the assembly is over, they will all return to their homes, very happily, anxious to read the compte-rendu of the party in the newspapers of the following day.

And the harmony of the university will not be perturbed. Nísia Floresta will continue to be forgotten; the gigolos will continue to make white women their slaves, the Chinese women will continue to torture their feet and the human intelligence will continue to be divided in two sexes: the masculine that leads Newton to discover the law of gravity and the feminine that makes us make stupid things.” (Lobato 2003 [1933], A feminina)

Gilberto Freyre was a Brazilian sociologist, historian, anthropologist, and writer, considered

one of the most important sociologists of the 20th century. In his 1936 book, Mansions and Shanties, he describes changes in the gender power dynamics of 19th-century Brazil, focusing specifically on the changes happening in the rural areas of the country. Freyre praises Floresta’s achievements in the world of letters in chapter four, “Woman and Man.”

“Due to the lack of femininity in its processes – in politics, literature, education, social welfare, and other areas of activity – Brazilian life suffered, through the splendor and, mainly, the decline of the patriarchal system. Only gradually did a more educated type of woman emerge out of pure domestic intimacy – a bit of literature, piano, singing, French, a pinch of science – to replace the ignorant mother who had almost no influence on their children besides a sentimental one, from the era of orthodox patriarchy. In literature, at the end of the 19th century, a Narcisa Amália emerged. Then, a Cármen Dolores. Even later, a Júlia Lopes de Almeida. Before them, there were almost only mediocre graduates, pedantic or simple-minded old maids, one or another Frenchified woman, some of whom were collaborators to the Luso-Brazilian Almanac of memories. And yet, they were rare. Nísia Floresta emerged – let it be repeated – as a scandalous exception. A true macho-woman among the bashful little ladies of the mid-19th century. Amidst men dominating all extra-domestic activities on their own, even baronesses and viscountesses barely knowing how to write, and the finest of ladies spelling out only devotionals and novels that were almost ‘stories of Trancoso,’ it is astonishing to see a figure like Nísia.” 366-367

7. Online resources

7.1 Podcasts

In English

Branscum, Olivia and Nastassja Pugliese. 2021. “Nísia Floresta Brasileira Augusta: Interview with Nastassja Pugliese.” New Voices: Extending New Narratives in the History of Philosophy. December 31, 2021. Podcast. 41 min.

In Portuguese

Lopes, Marcos and Nastassja Pugliese. 2015. “Filósofas Brasileiras no Século XIX – Interview with Nastassja Pugliese.” Filosofia Pop. May 18, 2015. Podcast. 103 minutes.

7.2 Video recordings of lectures about Floresta

In English

Pugliese, Nastassja. 2021. “Nísia Floresta’s critique of colonialism: Practical Cartesianism put to test.” Seminario de Investigadores, Instituto De Investigaciones Filosóficas-UNAM. November 10, 2021. Video. 107 minutes.

In Portuguese

Pallares-Burke, Maria Lúcia Garcia. 2021 “Nisia Floresta: Revisitando seu papel na história das ideias feministas e educacionais.” Vozes: Mulheres na História da Filosofia – UFRJ. June 1, 2021. Video. 85 minutes.

Arion, Vinicius, Maurício Rasia Cossio, and E Janyne Sattler. 2020. “Nísia Floresta e a Educação Para a Emancipação.” Uma Filósofa Por Mês. October 22, 2020. Video. 115 minutes.

7.3 Facsimiles of selected sources organized by original publication date

1838 (January 31st) – Jornal do Commercio – news on the opening of Colegio Augusto. Available here.

1839 (September 6) – Jornal do Commercio – news on the selling of the book Direitos. Available here.

1849 – First edition of the poem A Lágima de um Caeté. Available here.

1847 – Jornal O Mercantil – a critique of Colégio Augusto. Available here.

1853 – The first article of the serial newspaper publications of the work Opúsculo humanitário in Diário do Rio de Janeiro. Available here.

1855 – The first chapter of the serial newspaper publication of the work Páginas de uma vida obscura in O Brasil Ilustrado. Available here.

1853 -The first article of the serial newspaper publications of Opúsculo humanitário in O Liberal. Available here.

1864 – The book Trois ans en Italie is published. Volume 1: Available here. Volume 2: Available here.

1872 – A review of her book Trois ans en Italie where she is described as the “Brazilian de Stael.” Available here.

1879 (May 23) – the magazine O Novo Mundo (New York) published an article on Floresta with her most famous portrait. Available here.

1885 (April 24) – Two obituaries of Nísia Floresta: Jornal do Commercio (newspaper): Available here. O Paiz (newspaper): Available here.

1888 – First edition of the correspondence between Floresta and Auguste Comte. Available here.

1933 – Revista da semana: Available here.

1939 – Revista da semana: Available here.

1948 – Announcement of change of name of the city of Papari to Nisia Floresta: Available here.

1950 – Mundo Hispanico N.53, May, Madrid – Publishes comics dealing with Floresta’s life (page 7): Available here.

1954 – An official commemorative seal and stamp celebrating the transfer of Floresta’s body from France to Brazil so as to be reburied in her hometown. Available here.

Projeto Memória with images from Floresta’s life and works. Available here.

1996 – Reproduction of Lívia Augusta de Faria Rocha’s translation of La Donna to English, the essay Woman, accompanied with an introduction by Peggy Sharpe. Available here.