Emily Thomas’s post is part of our Revealing Voices blog series.

I was a doctoral student when I discovered that women philosophers had existed before the twentieth century. I was hunting for secondary literature on early modern theories of space, trawling shelf stickers and book spines. In a section of the library uninspiringly named “A 32” I came across Broad’s Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century. I plucked it in astonishment, supposing there must be some mistake. Women wrote poetry and novels back then, but they didn’t write philosophy. Broad’s book showed me otherwise, and it led me to many other works. I remember tracking down Waithe’s four-part History of Women Philosophers, and reading one subtitle in disbelief: Ancient Women Philosophers, 600 B.C. – 500 A.D.

Fascinating though this history was, it seemed a distraction. I returned to my thesis, which was about the relationship between absolute space and matter. Absolutists believe space is a being that exists independent of material bodies. It’s often described as a kind of infinite, eternal container in which stars, humans and other things move about. I had become interested in Newton’s absolutism. Newton’s De Gravitatione asks a simple question, What is space? His answer is labyrinthine, spraying metaphysically loaded terms in all directions. Newton writes that although space is not a substance it ‘approaches’ the nature of substance, and that space is an ‘emanative effect’ of God, and that space is ‘an affection’ of all beings. This has led to conflicting readings in the scholarship. (Personally, I read Newtonian space as a causal emanation of God, in reality identical with God— see here.)

My student self was coming to believe that Newton, and other early absolutists about space, aimed to advance theories that avoided two potential heresies. One is ‘polytheistic blasphemy’. On this heretical position space is a real being, distinct from God, that is possessed of God-like attributes, such as being eternal and infinite. Effectively, space would be a second God. The other heretical position is ‘pantheistic blasphemy’. This position identifies space with God in a way that smacks of Spinoza. Early moderns were leery of advancing any metaphysic reminiscent of Spinoza’s pantheism or ‘atheism’. I was starting to see the metaphysics of absolute space as a kind of puzzle: absolutists had to be wary of making space sound like a second God, or of identifying space with God. That left a limited number of positions, which may explain why Newton’s absolutism is so convoluted.

Although I was supposed to be working on Newton, Broad’s book was still swimming in my subconscious. I began reading early modern philosopher Catharine Trotter Cockburn, once described by John Toland as an ‘absolute Mistress of the most abstract Speculations in the Metaphysics’. I discovered that Cockburn advances an absolute account of space, and a new solution to the puzzle.

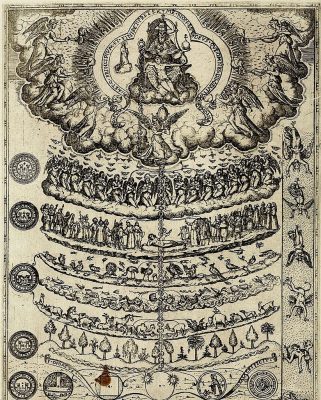

Cockburn’s 1743 “Cursory Thoughts” defends a metaphysical theory of reality, the Great Chain of Being. On this metaphysic every possible thing exists in a grand hierarchy. God sits at the top of the Great Chain, followed by immaterial spirits, humans, animals, plants and rocks. Each thing differs from the one below by subtle, gradual degrees. This chain involves two kinds of substance: material body and immaterial spirit. Yet Cockburn argues that, as matters stand, the Great Chain is unfinished. Body and spirit do not differ from each other by sufficiently gradual degrees, so ‘there should be in nature some being to fill up the vast chasm betwixt body and spirit’. To fill the gap, Cockburn posits a third substance: space. Like matter, space is unintelligent. Like spirit, space is immaterial.

Cockburn’s absolute space fills her gap in the Great Chain, and it provided a new solution to my puzzle. She avoids both heretical positions facing absolutism. Cockburn is not at risk of pantheistic blasphemy but she seems to be at risk of polytheistic blasphemy, as she holds space to be eternal and uncreated. Cockburn escapes this charge because her proof of absolute space necessarily places space lower than God in the Great Chain. Space is unintelligent and senseless, and such a being could never be a second God.

It’s been seven years since I opened the door on the history of women philosophers. Since then I’ve written about Cockburn’s absolutism, and the theories of several other women metaphysicians, including Anne Conway, Margaret Cavendish, Hilda Oakeley, and May Sinclair. It’s galvanising to uncover weighty philosophy that has been unjustly neglected. I also believe this area of scholarship could help the profession. Studies (see here and here) suggest one reason for the under-representation of women in philosophy is because philosophy is coded male. One way of breaking that coding is to show that the history of philosophy involves men and women. I teach women philosophers in my undergraduate course on early modern philosophy, and I’m glad my students learn sooner than I did of their existence.

Emily Thomas is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Durham University. She obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge and spent several years as a postdoc at the University of Groningen. In 2018 she published two books: Absolute Time: Rifts in Early Modern British Metaphysics, and Early Modern Women on Metaphysics. Follow her on Twitter @emilytwrites.

2 thoughts on “Revealing Voices: Emily Thomas”

Comments are closed.