This post is part of our Revealing Voices blog series.

There are two passions that drove me to philosophy. The first was a sense of wonder akin to what Aristotle described over two millennia ago in the opening line of his metaphysics. The second was a sense of horror.

Let me explain.

Ever since I was a young child, I desired to know whether there was a God, what was the stuff of reality, and were we souls trapped in bodies? And so in college I declared philosophy my major, and I went on to pursue my PhD in the history of philosophy. Once I was well into my graduate studies, however, the delight I used to take in contemplation had waned. By the time I was to declare a dissertation topic, I was seriously disenchanted. I was frustrated by the male-dominated climate and tired of the sexist comments of the great philosophers. I began to question whether I was a good fit for philosophy after all. I considered leaving the field.

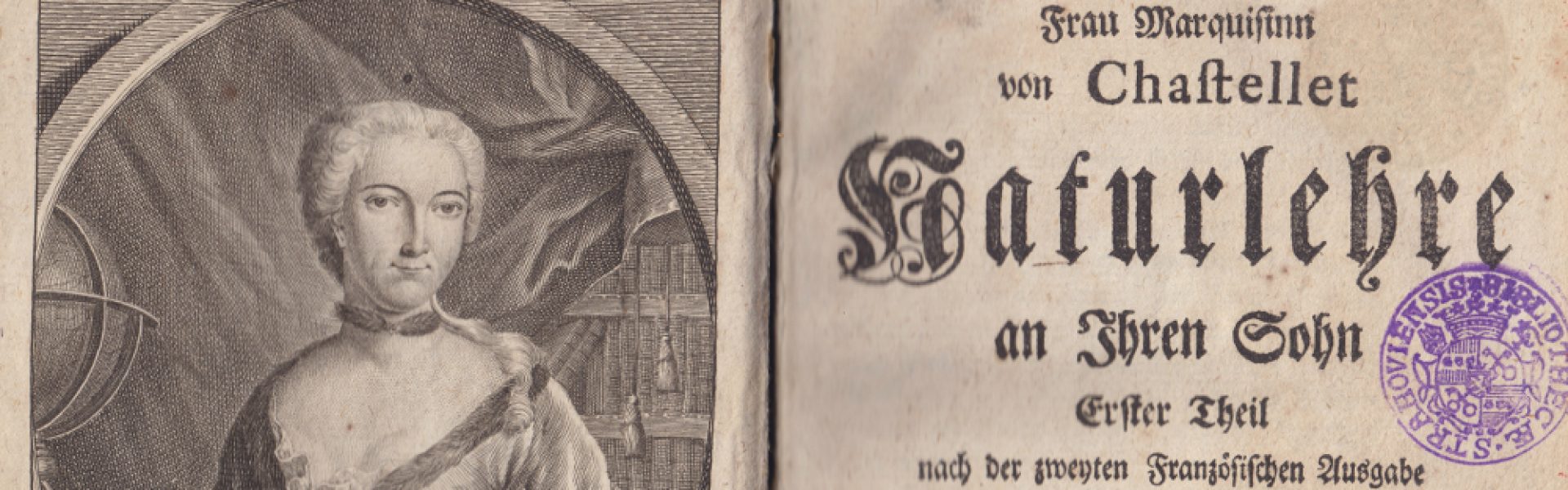

Then by chance I came across the work of a few obscure early modern women philosophers. I had no idea there were women doing philosophy in the time of Hobbes, Descartes, and Locke. I was shocked. I pored over their nearly-forgotten treatises, relishing their ideas and the amazing, yet small, body of scholarship on them at the time. Again wonder reeled me into philosophy. I wrote about Mary Astell (1666–1731), Damaris Masham (1659–1708), and Catharine Cockburn (1679–1749) for my dissertation. I later included Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) in my postdoc research. I got a tenure-track job.

Around the same time, I began to go through many changes in my personal life. I got a divorce, moved from the Midwest to New York City, and eventually found a new job, a new partner, had children, and ultimately left academia for journalism. But these early women philosophers never left me. In fact, I was in awe of how their lives and ideas resonated with my own. They were conversant in the metaphysics, epistemologies, ethics, and political theories of their day, but they were also interested in topics such as how social conditioning stifles women, the nature of motherhood, the significance of marriage, and women’s intellectual autonomy, to name just a few. These women philosophers gave me insight into how to be a person in the world in ways that Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Kant never did.

I wondered why we don’t know about them. Why are they not part of the curriculum in philosophy? Why do people speak of philosophy as the field of “dead white men” when there were many philosophers of color and women philosophers from the past? Not only were these thinkers erased from the history of philosophy as it’s normally taught, but their questions and concerns, such as those aimed at the condition of women, were excluded from the history of philosophy. A consequence of this is it makes it seem as if feminist thought is a relatively modern invention of Mary Wollstonecraft. It’s not. Feminist thinking is as old as philosophy itself.

This shouldn’t be that surprising. Women’s experience is human experience. Why and how philosophy has succeeded in separating these two and dismissing women’s experience as “niche” or “feminist” or “self-help” rather than part of a good life project is an open question. (That feminist philosophy is often categorized as an elective course and rarely taught by men are examples of this). I have my suspicions for why this happens, which have to do with cooking, diapers, and ego-stroking.

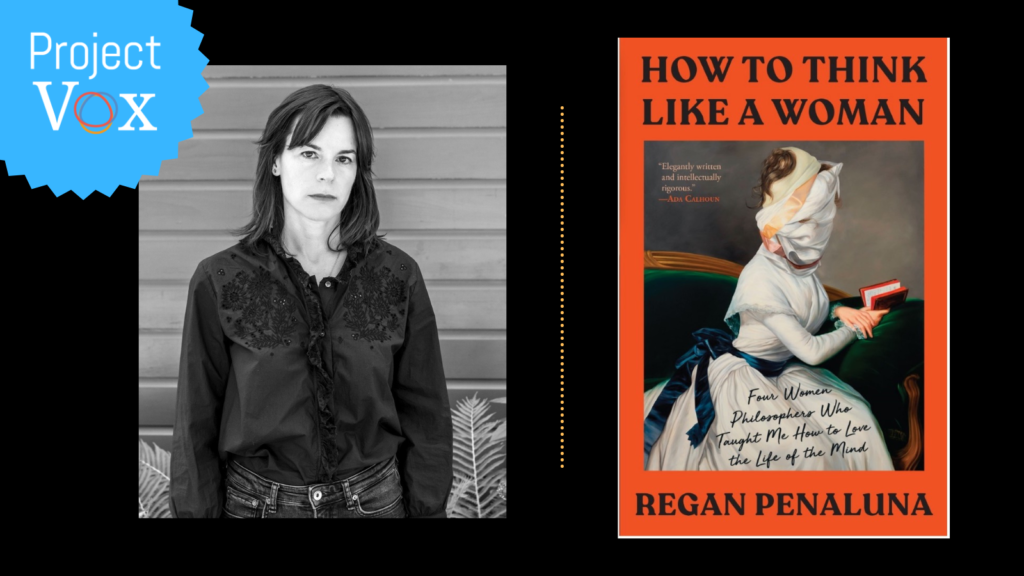

I write about all of this in greater detail in my book How To Think Like A Woman: four women philosophers who taught me how to love the life of the mind. I wish to bring these important thinkers to the attention of a wider audience, which they deserve. My book is also an attempt to illuminate what often remains hidden: the forces of oppression that silence women and erase their work. My book builds the case that women’s absence from the history of philosophy is not because there were no women philosophers or due to an accident, but rather because of an entrenched prejudice against women’s perspectives as relevant to the human condition. The lack of sympathy among many philosophers for women can’t be dismissed as charmingly oafish or because metaphysics is the queen science (as if metaphysics itself is unrelated to the human condition). We need to call it what it is: unethical.

And so, despite leaving academia years ago, I still circle around this field that I love, reading, writing, and thinking about philosophy in my own idiosyncratic ways, and especially enjoying the burst of scholarship on early women philosophers. The wonder that originally drew me to philosophy has been joined by another passion, a sense of horror for how philosophy suppresses women, and a wish to grasp this leviathan and force it into the light.

Regan Penaluna is a writer and journalist based in Brooklyn. She holds a master’s in journalism and a PhD in philosophy. Previously, she was an editor at Nautilus Magazine and Guernica, where she wrote and edited long-form stories and interviews. A feature she wrote was listed in the Atlantic as one of “100 Exceptional Works of Journalism.” Her book How To Think Like a Woman is available from Grove Atlantic Press. You can follow her on Twitter @reganpenaluna.