This post, authored by Yasemin Altun, is part of our Behind the Scenes blog series.

Allow me, briefly, to judge a website by its cover. Type to the front page of projectvox.org and a carrousel of images immediately fills your screen. Women of varied gazes and guises face you for a moment, before dissolving into the virtual abyss. They graze your attention as you curiously click on to a new page to learn more. These portraits and frontispieces are the “faces” of Project Vox. They represent the philosophers we feature in biographical, critical texts on our site. As banner images played on a loop, they recall two visual traditions. First, the slide projectors that since the 1960s brought hazy Rembrandts and Gentileschis to dimmed lecture halls and that are a now a nostalgic bit of art history. Second, the standard in scholarly publishing of giving a face to a newly edited volume of early modern philosophy, literature, etc. by reproducing a portrait of its author on the cover. These two practices inform Project Vox’s engaging use of images not only on its homepage, but throughout the site as a pedagogical compliment to its philosopher entries.

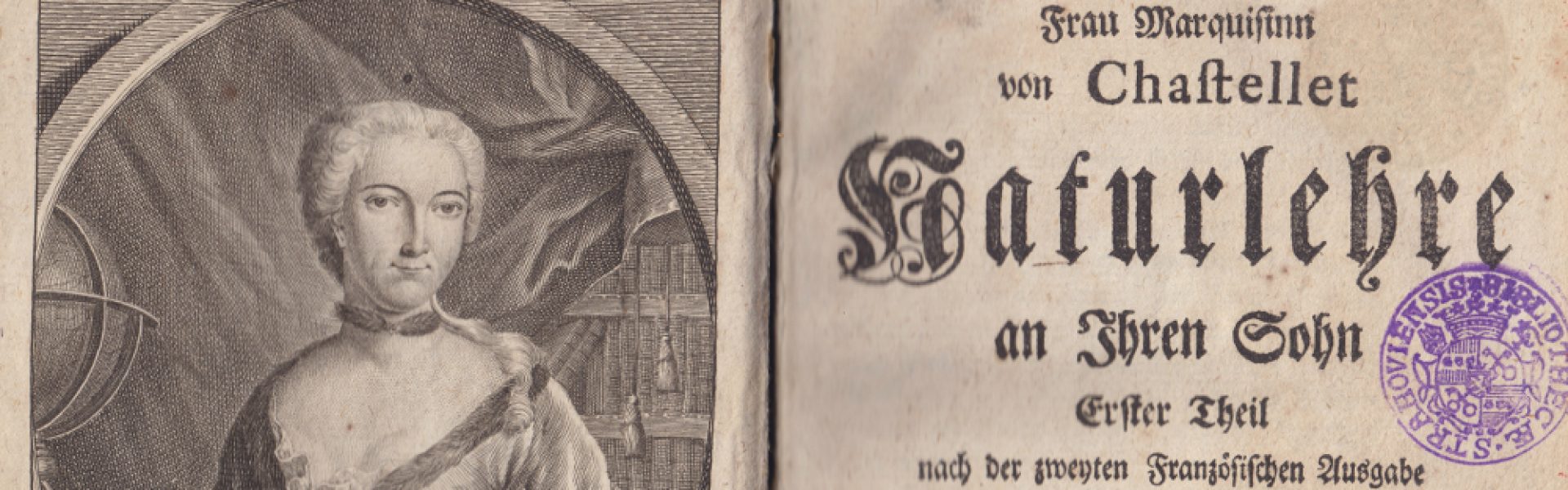

Project Vox has always been a visual platform. This was revealed to me at a recent team meeting led by Will Shaw, the Project’s Technical Lead. Since its first entry on Émilie Du Châtelet in 2014, Project Vox has published a selection of contextual images alongside every featured philosopher. Since then, the Image Gallery has grown to encompass over 300 works of art and visual culture, ranging from Van Schurman’s embroidery to Sor Juana’s signature in blood. Our documentation for each image has become more robust and tailored to reflect art historical interests in a work’s medium, scale, and maker(s). We have also become more sensitive to responsibly sourcing and citing the images reproduced on our site. Reflecting on that evolution, this post surveys three cases of images research done by Project Vox in recent years. It discusses the Project’s integration of art historical methods that have proven useful for shaping its own public face as an open-access, educational resource on marginalized voices in early modern philosophy.

Picturing Without a Portrait: The Case of Mary Shepherd

In the spring of 2021, Project Vox published its entry on the Scottish philosopher Mary Shepherd. Shepherd presented the PV team with new challenges. We did most of the preparation in the early throes of the pandemic, when graphics circulated the web reminding people to social distance. (My favorite is one that used hula-hooping as a gauge.) Daily news about climbing cases of infection made the situation clear: physical connection was taboo. With in-person meetings unfeasible in the foreseeable future, digital tools like Zoom became crucial for communicating as a team. Others like Facebook and Twitter proved equally essential for staying engaged with our audiences. Dedication to these tools allowed Project Vox to manage the difficulties of collaborative research during a pandemic and continue its mission to spread knowledge about underrepresented philosophers like Shepherd.

In this case, connection became a theme of our collective thinking. Other members of the team began a promising project to map the cultural networks that linked Shepherd with other philosophers and to visualize the breadth of her intellectual impact in the British Isles. Meanwhile, the Images sub-team faced a dilemma: how could we “picture” Shepherd without a mature portrait of her? As art historian Marcia Pointon has studied, portraiture was a key social currency in Britain during Shepherd’s lifetime (Pointon 1993). Yet beyond one family portrait painted when Shepherd was eleven, we could locate no image of her made during the decades of her career in Edinburgh and London. So instead, we pieced together a mosaic of maps, frontispieces, and portraits of her interlocutors that together gave a sense of her cultural milieu and intellectual biography. Perhaps the star find was a cartoon drawn by Daniel MacClise of a contemporary salon run by Lady Blessington. We can imagine Shepherd as one of the women portrayed here, who by conversing with others helped to shape the ideas trending in early-nineteenth-century London. This cartoon advances a key effort of Project Vox to recover the lives and ideas of people whose writings made them familiar in their time, but whose gender, among other identities, have led to their underrepresentation in canonical, modern histories of philosophy.

Frontispiece Method: The Case of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Project Vox also executed its entry on Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz during the pandemic’s infancy. On this occasion, we were lucky to collaborate with two scholars of Sor Juana’s philosophy then external to Duke, Sofia Ortiz-Hinojosa and Sergio A. Gallegos Ordorica. Sofia and Sergio generously shared their expertise about Sor Juana’s intellectual milieu, which proved crucial for compiling a visual corpus that reflected her melding of Western and indigenous Mexican worlds. In turn, this past summer, Project Vox updated its entry on Sor Juana. The Images sub-team added analysis of one frontispiece that was originally published with the Sor Juana entry in April 2021. This frontispiece accompanied the posthumous release of her Fama, y obras posthumas in 1700. Its commentary in the Project Vox entry began life as a term paper written by an undergraduate student here at Duke in the fall of 2021. The course was taught by Professor Susanna Caviglia in the department of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies. Professor Caviglia’s course focused on women in the visual arts during the early modern period. One of the excellent papers written for her class concerned this frontispiece.

A frontispiece refers to the printed illustration that usually faces the title page of a published volume. In the early modern period, these images made a pointed statement about the text that followed and/or its author(s). They could visualize a scene within the novel or play. They could allegorize a key philosophical concept in the text. Or they could canonize its author with a portrait crafted to broadcast symbols resonant with contemporary readers. Simply, frontispieces made a visual argument about the text. They were meant to introduce readers to a text and sway their view of its author or subject. Project Vox aims to achieve something similar with every image it publishes in relation to its philosopher entries. Our goal is to present the fullest possible picture of a historical figure or concept. That includes portraits, maps, frontispieces, signatures, and any other visual information that illustrates the intellectual connections of a philosopher and supports our claim for her re-insertion into the history of philosophy.

The way most of us interact with images today—scrolling, zooming, filtering—has resulted in an at once passive yet hyper-sensitive relationship to looking. It is no secret that social media and internet browsing at large have altered our perception of time and our ability to focus. This has made prolonged, critical reflection on one still image increasingly unintuitive. Yet platforms like Facebook and eventually Instagram have proven that the curation of one’s identity through visual media is just as relevant today as it was in 1700. Indeed, philosophers like Sor Juana were astutely aware of the power of portraits to advance their social and/or ideological goals. We can detect this in the paintings of Sor Juana in her study, but also in posthumous images like the above frontispiece. As discussed in our update to the Sor Juana entry (under Section 2. “Primary Sources Guide”), this image uniquely conveys her legacy as an intermediary between classical Western and indigenous Mexican religious and intellectual traditions. Like the anthology Fama y obras póstumas itself, this image is a composite of contemporary references to other figures, ideas, and motifs that situate Sor Juana as an active philosopher of her time.

Plans For the Past: The Case of Émilie du Châtelet

As Project Vox looks to the future—lengthens its list of philosophers, broadens its audience, and welcomes the insights of external collaborators—its past looms larger. Typos on the site become jarring, information becomes outdated or incomplete. One of the perks of digital publishing is that it moves at a faster pace than print. Rather than indulge an impulse for production, this feature should be harnessed for the cause of revision. The concept is familiar: Project Vox’s mission after all is to continuously revise the canon toward a more complete history of philosophy. That ethos must turn inward. To be clear, this is not a plea for the Project to “stay relevant.” It is merely a reminder that as the Project grows it will become absorbed by the canon, and therefore assume new responsibilities. Chief among them is maintaining the website so that it best represents the interests of our audiences and the work of our philosophers.

This will look like many things. It will entail editing images’ captions and citations to achieve a greater consistency across the site as it has evolved, while retaining our own vintage. That is, treating the website as an archive of the Project’s evolution with images since 2014 and resisting the urge to erase all evidence of mistakes and thus improvement. Revision would also involve updating the bibliography for each philosophy entry to reflect the most recent scholarship. Or adding new syllabi, images, translations, or accessibility features to other realms of the site. Even incorporating fresh commentary from student contributors on material we have already published. For example, with the Sor Juana frontispiece discussed above. Or with portraits of the Marquise Du Châtelet. In fall 2020, other students in Professor Caviglia’s class wrote essays on portraits of Du Châtelet done by Quentin de La Tour and a little-known woman artist named Marianne Loir. Their essays were edited by the Images sub-team and incorporated into the portraits section of the Du Châtelet entry this past summer. These additions have enriched the entry by filling out its own portrait of Du Châtelet as a respected femme de lettres, an aristocratic woman, and a partner of Voltaire. They attest to Project Vox’s commitment to vertical collaboration between undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and staff across disciplines.

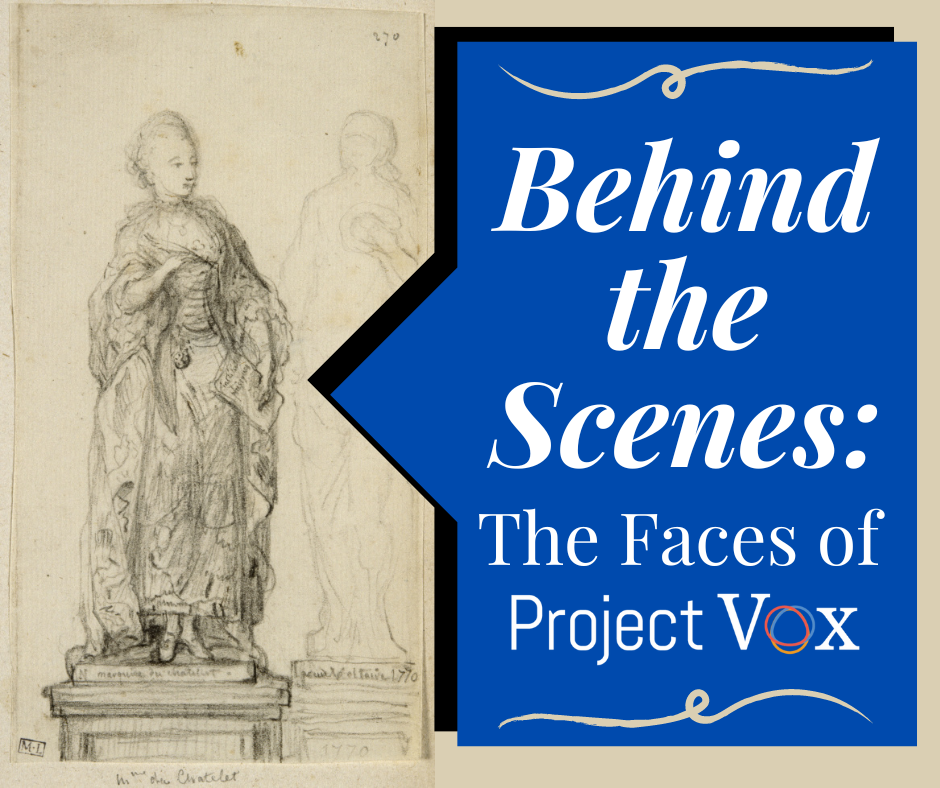

To conclude, I will share an excerpt from another recent revision to the Du Châtelet entry. It is an image that uniquely portrays her legacy as an Enlightenment philosopher. Yet, to my knowledge it has been largely overlooked in Du Châtelet scholarship.

This sketch was done by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin in 1770. It depicts a portrait statue of Du Châtelet, identifiable by the inscription on its base. Saint-Aubin designed the statue for a never-realized sculpture series of Great Women. As in Du Châtelet’s other portraits, her attire in this drawing matches the persona of an aristocratic woman. She wears a patterned dress with fitted bodice that gives a slender curve to her frame and rhymes with the dainty shape of her feet. Her dress sports frills of chiffon at the neck and lace sleeves that cascade down her sides. We can even detect a timepiece hanging from her waist.

Saint-Aubin’s drawing is particularly striking in how it stages Du Châtelet’s intellectual relationship with Voltaire. Du Châtelet looks to the left in the direction of a faintly sketched statue, labelled as Voltaire at its base. His head appears turned to the right, returning Du Châtelet’s look as if in conversation with her or as her mirror reflection. In fact, another, contemporary frontispiece reproduced in Project Vox’s entry on Du Châtelet positions her as a mere reflection or conduit of Newton’s ideas for Voltaire. By contrast, this drawing foregrounds Du Châtelet. Her statue is drawn in dark relief whereas the statue of Voltaire is just lightly outlined in the background. The similar physical size of each statue alludes to the parity of their legacies as philosophes.

The addition of this little-known image to the Du Châtelet entry represents one of the endless possibilities of growth for Project Vox and for the discipline it seeks to improve. As with philosophy’s canon, this growth must occur alongside adjustments to our past.

Yasemin Altun is the Images Research Lead for Project Vox and a Ph.D. Candidate in Art History and Visual Culture at Duke University.

One thought on “Behind the Scenes: The Faces of Project Vox”

Comments are closed.