Theresa Helke’s post is part of our Revealing Voices blog series.

Roy Auh: How did you first hear of Project Vox?

Theresa Helke: I was trying to design a curriculum in the philosophy of language, looking to include a variety of voices and I’d been struggling, when I found among the results a couple of articles – one in The Washington Post, another in The Atlantic – discussing Andrew Janiak and Project Vox.

RA: For that course, what were some of your objectives and how did you meet them?

TH: Among the measurable objectives was that students be able to propose a way to change the status quo in philosophy. Among the less measurable, that they develop marketable skills and the ability to communicate them.

I started discussing the status quo in the first class. To be able to propose a way to change it, students needed to be aware of the status quo. I’d designed a scavenger hunt activity to allow students to get to know each other, and me to get to know my students.

Among the questions on the sheet was this one: “Find someone who can name three philosophers”. When we debriefed, I found the students had collectively offered fifteen names of philosophers. When I asked students what they noticed about that list, it didn’t take long for one to comment on the gender disparity.

One belonged to a woman (de Beauvoir) and fourteen belonged to men (in alphabetical order, Aristotle, Descartes, Foucault, Frege, Hume, Kant, Locke, Montague, Nietzsche, Plato, Russell, Sartre, Socrates, Wittgenstein). (A further point I could’ve made was that all thinkers were white.)

Later, I introduced students to a tool for evaluating representation in texts: the Philosophy Bechdel Test.

To meet this objective – that they be able to propose a way to change the status quo – I invited students to do two things: stay in the course! I was teaching at a historically women’s college. Most of the students in the classroom at Smith weren’t represented in most philosophy of language curricula. And their doing philosophy would in and of itself be disruptive to the prevailing narrative.

The second thing – and this relates also to the objective of developing marketable skills and the ability to communicate them – was to complete a final assignment which dovetailed with Project Vox’s work.

RA: That is quite the opening to the semester! How did you then come to collaborate with Project Vox, and how was your experience doing so?

TH: I wrote to the address I found on the website. In the weeks that followed, I exchanged e-mails with Andrew, and we spoke twice on FaceTime. My experience was overwhelmingly positive. Andrew appeared interested in collaborating and supportive, and sent materials on which my students could work.

RA: What was the final assignment?

TH: The final assignment was to “design and execute a project relating to the philosophy of language which can

- help students or teachers seeking to engage with philosophers (whom perhaps the canon currently doesn’t include?) to engage with some; and

- help you build your resume.”

Among the ideas I presented, one directed students to Project Vox:

- participate in the translation of a text for Project Vox and write about the problem of translation in the philosophy of language;

RA: So what Project-Vox-related projects did your students undertake?

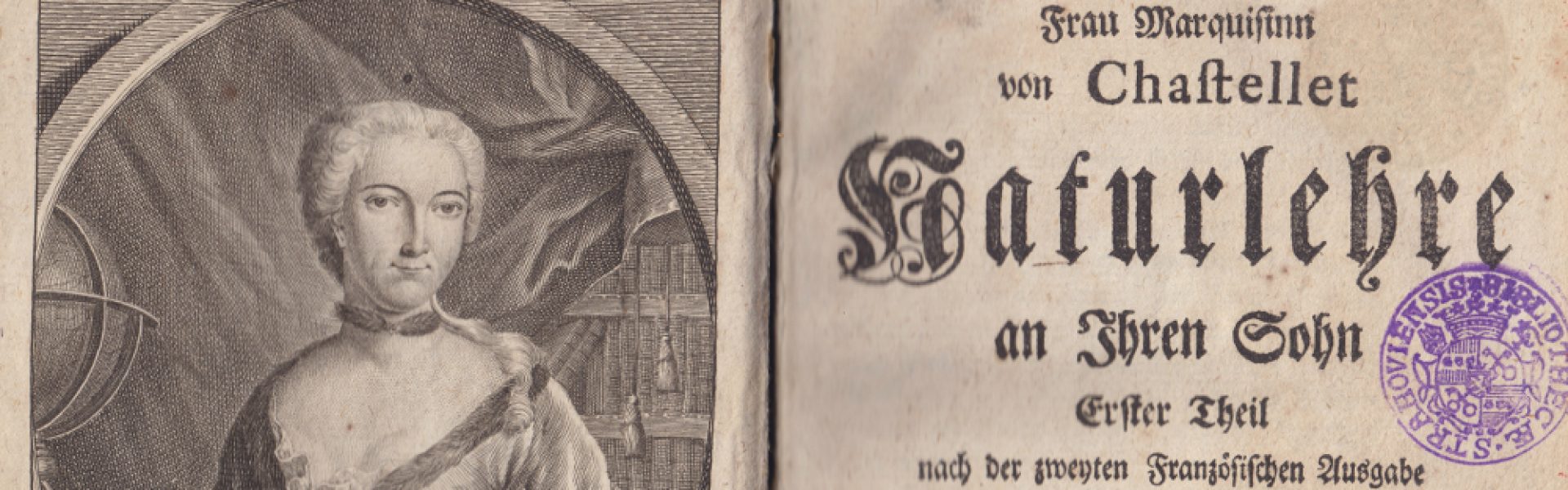

TH: One project featured the following two parts: on the one hand, a translation of two texts that Anna Maria van Schurman sent to Marie Jars de Gourney, both of which were among those that Andrew had sent to me. The first is a letter, which van Schurman wrote in 17th century French. The second is a poem, which she composed in classical Latin.

On the other hand, the project featured an argumentative essay, defending the idea that there are two ways in which a translator can warp meaning: “under-translation”, where the meaning she conveys in the target-language is deficient, failing to include a meaning from the source-language; and “over-translation”, where the meaning the translator conveys in the target-language is excessive, introducing a meaning which wasn’t present in the source-language. The student illustrated these ideas, analysing Anne Larsen’s translation of the Latin poem, and comparing it to her own.

This project met the two-part brief I mentioned before. On the one hand, it helped students or teachers seeking to engage with philosophers (whom perhaps the canon currently doesn’t include) to engage with some. Indeed, it made available to people who only speak English two texts by a woman philosopher. On the other hand, it helped the student build her resume. It allowed her to develop her language and translation skills.

RA: The project sounds fascinating. I would love to look at it in the future! Until then, what’s next?

TH: Another collaboration, I hope, with Project Vox. Next year, I’m due to teach the philosophy of language course again and I’d like to run a similar final project. This time, to scaffold the work of students undertaking a translation, I want to organize a French translation slam. Even without the relevant linguistic skills, students could work with a dictionary. I could coach them—I grew up in Geneva, speaking French. I could also recruit students taking French classes who are willing to come and help.

RA: This is our first time collaborating with a course outside of Duke, and so I’m just really glad to see how well it worked out. More collaboration would definitely be possible. Thank you for your great work and telling us about it!

Theresa Helke is a lecturer in the Department of Philosophy and Program in Logic at Smith College, MA. She received her PhD from the National University of Singapore and Yale-NUS College, writing a dissertation on indicative conditionals and apparent counterexamples to modus ponens and modus tollens. Before assuming her current position, she served as a Rural Community Health Coordinator in the Peace Corps in Benin.

One thought on “Revealing Voices: Theresa Helke”

Comments are closed.